F1909.168 Documentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Analysis of the Visual Language Features of Chinese Ink and Wash Landscape Paintings

2021 4th International Conference on Arts, Linguistics, Literature and Humanities (ICALLH 2021) A Brief Analysis of the Visual Language Features of Chinese Ink and Wash Landscape Paintings Lai Yingqin Dept of Ceramic Art, Quanzhou Vocational College of Arts and Crafts, Quanzhou, 362500, China Keywords: Chinese painting, Ink, Landscape, Visual language Abstract: Ink and wash can be connected into lines by brushing, rubbing, drawing, drawing, and drawing on rice paper, and the points can be connected into lines, and the lines can be gathered into surfaces, and the surface can be transformed into a space with both virtual and real. Ink and wash landscape paintings are shaped in this way. A visual language that speaks less and more. It can describe both the real scene that people see, and the illusory scene that people see. That's it, the visual language of ink and wash landscape painting can be brilliant and intoxicating. It is based on the specific performance of stippling, which gives people a visual impact, and is laid out in the invisible surroundings, making people think about the scenery. 1. Introduction Since entering the modern industrialized society, due to the profound influence of modern industrialization culture, especially machine aesthetics, art design culture is in the ascendant, in the field of visual design, people can see images everywhere, such as “font design, logo design, illustration” Design, layout design, advertising design, film and television design, packaging design, book binding design, CIS design, display design, graphic design, etc.” (1), all have entered the field of vision of people, and even some product designs (including industrial product design, The content and form of home design, clothing design) and space design (including indoor and outdoor design, display design, architectural design, garden design and urban design) have also entered people’s vision as visual content. -

![[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1753/re-viewing-the-chinese-landscape-imaging-the-body-in-visible-in-shanshuihua-1061753.webp)

[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫

[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫 Lim Chye Hong 林彩鳳 A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chinese Studies School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Australia abstract This thesis, titled '[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫,' examines shanshuihua as a 'theoretical object' through the intervention of the present. In doing so, the study uses the body as an emblem for going beyond the surface appearance of a shanshuihua. This new strategy for interpreting shanshuihua proposes a 'Chinese' way of situating bodily consciousness. Thus, this study is not about shanshuihua in a general sense. Instead, it focuses on the emergence and codification of shanshuihua in the tenth and eleventh centuries with particular emphasis on the cultural construction of landscape via the agency of the body. On one level the thesis is a comprehensive study of the ideas of the body in shanshuihua, and on another it is a review of shanshuihua through situating bodily consciousness. The approach is not an abstract search for meaning but, rather, is empirically anchored within a heuristic and phenomenological framework. This framework utilises primary and secondary sources on art history and theory, sinology, medical and intellectual history, ii Chinese philosophy, phenomenology, human geography, cultural studies, and selected landscape texts. This study argues that shanshuihua needs to be understood and read not just as an image but also as a creative transformative process that is inevitably bound up with the body. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 469 Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2020) "Evaluating Painters All Over the Country" Guo Xi and His Landscape Painting Min Ma1,* 1Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Styled Chunfu, Guo Xi was a native of Wenxian County. In the beginning, he learned from the methods of Li Cheng, yet he was rather good at expressing his own feelings, thus becoming adept at surpassing his master and creating a main school of the royal court landscape painting in the Northern Song Dynasty whose influence had lasted to later ages. Linquan Gaozhi Ji, Guo Xi's well-known theory on landscape painting, was a book emerged after the art of landscape painting in the became highly mature in the Northern Song Dynasty, which was an unprecedented peak in landscape painting and a rich treasure house in the history of landscape painting. Keywords: Guo Xi, Linquan Gaozhi, landscape painting Linquan Gaozhi Ji wrote by Guo Xi and his son I. INTRODUCTION Guo Si in 1080 was a classic book on landscape Great progress had been made in the creation of painting as the art of landscape painting became highly panoramic landscape paintings in China during the mature in the Northern Song Dynasty. The book was Northern Song Dynasty, after the innovations of Jing written in the late Northern Song Dynasty, when the art Hao, Guan Tong, Dong Yuan and Ju Ran, when a of landscape painting in China had already entered a number of influential landscape painters and exquisite relatively mature stage. -

The Donkey Rider As Icon: Li Cheng and Early Chinese Landscape Painting Author(S): Peter C

The Donkey Rider as Icon: Li Cheng and Early Chinese Landscape Painting Author(s): Peter C. Sturman Source: Artibus Asiae, Vol. 55, No. 1/2 (1995), pp. 43-97 Published by: Artibus Asiae Publishers Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3249762 . Accessed: 05/08/2011 12:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Artibus Asiae Publishers is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus Asiae. http://www.jstor.org PETER C. STURMAN THE DONKEY RIDER AS ICON: LI CHENG AND EARLY CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING* he countryis broken,mountains and rivers With thesefamous words that lamentthe "T remain."'I 1T catastropheof the An LushanRebellion, the poet Du Fu (712-70) reflectedupon a fundamental principle in China:dynasties may come and go, but landscapeis eternal.It is a principleaffirmed with remarkablepower in the paintingsthat emergedfrom the rubbleof Du Fu'sdynasty some two hundredyears later. I speakof the magnificentscrolls of the tenth and eleventhcenturies belonging to the relativelytightly circumscribedtradition from Jing Hao (activeca. 875-925)to Guo Xi (ca. Ooo-9go)known todayas monumentallandscape painting. The landscapeis presentedas timeless. We lose ourselvesin the believabilityof its images,accept them as less the productof humanminds and handsthan as the recordof a greatertruth. -

The Creations and Research in the Regional Landscape Spirit of Heilongjiang Province

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 8, No. 3, 2012, pp. 76-80 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020120803.3025 www.cscanada.org The Creations and Research in the Regional Landscape Spirit of Heilongjiang Province DU Xuehui[a],* [a] Art School, Harbin Normal University, Heilongjian, China. administrations here successively, namely, Shiwei * Corresponding author. Administration, Heishui Administration and Bohai Supported by Project No. 1154G33. Administration. After Qidan tribe had conquered Bohai Kingdom, the Dongdan State was established here. The Received 21 May 2012; accepted 10 June 2012 Jin State set its capital city at Huiningfu (now named as Baicheng of Acheng City of Heilongjiang province). Abstract After Yanjing City (now as Beijing, also Peking) was Heilongjiang Province is located in the northeastern set as the capital by Yuan Dynasty (1271AD~1368AD), border part of People's Republic of China. Compared this region was set as part of Liaoyang Province. Ming with those coastal provinces, the inner land provinces Dynasty (1368AD~1644AD) founded Nuergan Regional are less developed economically or culturally. However, Administration here which governed 384 Weis (a military the discovery of Hongshan civilization, the brilliant rank which consisted of 5,600 soldiers or so) and 24 Suos civilization of Bohai Kingdom which was affi liated to the (also a military unit which is ranked lower than Wei). Tang Dynasty (618AD~907AD), the nomadic and agro- The Qing Dynasty (1644AD~1912AD, the last feudalist culture of the ethnic groups of Jurchens minority(the empery in Chinese history) also founded a regional ancestry of Manchu minority), Manchu minority and administration here which was named as Niguta, and was Mongolian minority, and the Russian culture deposit, later renamed as Jilin General. -

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill Note: the Image Numbers in These Lecture

Lecture Notes, by James Cahill Note: The image numbers in these lecture notes do not exactly coincide with the images onscreen but are meant to be reference points in the lectures’ progression. Lecture 4B. Tang Landscape Painting What follows is part two of lecture 4, in which we will look at some of the scant evidence that survives for what must have been a great development, now mostly lost, of landscape painting in the Tang period. We’re still dealing with a few fragments and some paintings we can take to be copies of Tang works, of uncertain reliability. But even these give us some sense of the very important developments of this period, as we read of them in the writings of the time and later. Landscape was becoming established as a separate genre of painting, still secondary to figure and religious painting but now absorbing the efforts of major masters, and being the principal concern of a few of them. Something approaching “pure” landscape must already have existed in the pre-Tang period, if we believe the writings of Zong Bing and others. But now we can observe the early stages of its development in the Tang. Image 4.14.0: wall painting (copy) in the tomb of Prince Yide 懿德, early Tang ( 3000 , 39, where the landscape is unclear). The artist is actually known: the name Chang Bian is inscribed on it; he is recorded as a follower of Li Sixun 李思訓. This identification was made, as I recall, in a catalog by Jan Fontein of an exhibition he organized of copies of Tang wall paintings while he was curator at Boston MFA. -

Wu Zhen's Poetic Inscriptions on Paintings1 - School of Oriental and African Studies

Wu Zhen's poetic inscriptions on paintings1 - School of Oriental and African Studies Introduction Wu Zhen (1280–1354), style name Zhonggui, also called himself Meihua Daoren (Plum Blossom Daoist Priest), Mei Shami (Plum Priest) and Meihua Heshang (Plum Blossom Priest). He came from Weitang, now known as Chengguan, in Zhejiang Province. Along with Huang Gongwang (1269–1354), Ni Zan (1301–74), and Wang Meng (1308–85), he is known as one of the ‘Four Great Painters of the Yuan Dynasty’.2 Wu Zhen was also one of the leading figures of Chinese literati painting at the height of its popularity. When painting landscapes, or bamboo and rocks, he would usually inscribe his works with poems, and his contemporaries praised his perfection in poetry, calligraphy and painting, or the phenomenon of sanjue, ‘the three perfections’.3 Research to date has concentrated on Wu Zhen's paintings,4 but his poetic inscriptions have been relatively neglected. This article seeks to redress the balance by focusing on Wu Zhen's poetic inscriptions on paintings, both his own and those of past masters, and argues that inscriptions and colophons are an essential key to understanding literati art. Wu Zhen's family background is difficult to ascertain, since only very limited accounts of his life can be found in Yuan period sources.5 Sun Zuo (active mid to late fourteenth century)mentions Wu Zhen's residential neigh- bourhood, painting skills and character, without going into any depth.6 After the mid-Ming period, legends about Wu Zhen developed, and these provide us with some useful material. -

Cleveland Museum of Art Photograph Library National Palace Museum

Cleveland Museum of Art Photograph Library National Palace Museum, Taipei Collection Artist Index: Painting & Calligraphy Prepared by K. Sarah Ostrach Updated July 31, 2020 Contents Unknown Dynasty ........................................................................................................... 2 Age of Disunion ............................................................................................................... 2 Sui Dynasty ..................................................................................................................... 2 Tang Dynasty .................................................................................................................. 2 Five Dynasties ................................................................................................................. 3 Song Dynasty .................................................................................................................. 3 Yuan Dynasty .................................................................................................................. 7 Ming Dynasty ................................................................................................................ 10 Qing Dynasty ................................................................................................................. 15 Unknown Dynasty Box # Unknown Artists 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Wu Gengsheng (Wu Keng-sheng --更生) 4 Zhang (Chang) 4 Age of Disunion Box # Gu Kaizhi (Ku K'ai-chih 顾恺之) 6 Wang Xizhi (Wang Hsi-chih 王羲之) 6 Zhang Sengyou (Chang -

Chinese Brush Painting Pdf Free Download

CHINESE BRUSH PAINTING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lucy Wang | 32 pages | 01 Jan 2003 | Walter Foster Publishing | 9781560101666 | English | Laguna Hills, CA, United States Chinese Brush Painting PDF Book This assimilation is also recorded in a poem by poet from Six Dynasty period who pointed out that the beauty and nominosity of the mountain can elevate the spiritual connection between human being and the spirits. However, during the Song period, there were many acclaimed court painters and they were highly esteemed by emperors and the royal family. Study and copy the work of the masters. Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 85, times. The artists began to show space and depth in their works where they showed mountain mass, distanced hills and clouds. Reserve your tickets. Namespaces Article Talk. Located deeply in a village, the water mill is driven by the force of a huge, vertical waterwheel which is powered by a sluice gate. Related wikiHows. In contrast to what most of us are taught about art today, copying and perfection of technique was more important and more highly valued than self-expression. During the Tang dynasty , figure painting flourished at the royal court. The early themes of poems, artworks are associated with agriculture and everyday life associates with fields, animals. The shan shui style painting—"shan" meaning mountain, and "shui" meaning river—became prominent in Chinese landscape art. There was a significant difference in painting trends between the Northern Song period — and Southern Song period — Taoism influence on people's appreciation of landscaping deceased and nature worshipping superseded. -

5 the Suspension of Dynastic Time

5 The Suspension of Dynastic Time JONATHAN HAY In the conventional historical record, China's history appears as a succession of dynasties, a succession that is often complicated by the division of the country into areas under the rule of different regimes. But like the official maps of the London underground and the New York subway, which stretch, shorten, straighten and bend to create an illusion of carefully planned order, the chronological tables of Chinese history represent a ferocious editing of the historical process. The boundaries between dynasties were far from unambiguous to those who lived them. In this essay, I shall try to reconstruct some of the ambiguities of one such boundary, that between the Ming and the Qing dynasties, from the point of view of painting. The focus will be on what I shall call 'remnant' art, that is; the art of those intellectuals who defined themselves as the 'remnant subjects' (yimin), of the Ming dynasty! Still more narrowly, I shall largely be concerned with two closely related painters working in the city of Nanjing, formerly China's southern capital under the Ming dynasty. Zhang Feng (died 1662) and Gong Xian (1619-89) are just two of many remnant artists who congregated in the suburbs of Nanjing, where the temples offered safe haven to Ming sympathizers and the Ming monuments were visible reminders of the previous dynasty.' The works I shall discuss are landscapes which exploit the heritage of landscape painting as the pre-eminent genre for the metaphoric exploration of the individual's relation to state and nation. -

Semiotics for Art History

Semiotics for Art History Semiotics for Art History: Reinterpreting the Development of Chinese Landscape Painting By Lian Duan Semiotics for Art History: Reinterpreting the Development of Chinese Landscape Painting By Lian Duan This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Lian Duan All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1855-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1855-1 This book is dedicated to Dr. David Pariser who has given me lifelong scholarly guidance. For my mother, who is always supportive, spiritually. In memory of Peter Fuller (1947-1990) who paved the road for me to approaching art. CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements ................................................................................... xii Preface ...................................................................................................... xiv David Pariser Endorsement ............................................................................................ xvii Mieke Bal Introduction ................................................................................................ -

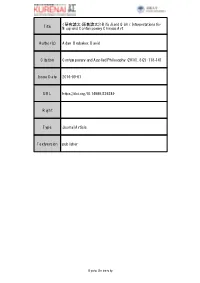

Title <研究論文(原著論文)>Bifa Ji and Qizhi: Interpretations for Muqi And

<研究論文(原著論文)>Bifa Ji and Qizhi: Interpretations for Title Muqi and Contemporary Chinese Art Author(s) Adam Brubaker, David Citation Contemporary and Applied Philosophy (2016), 8(2): 118-141 Issue Date 2016-09-01 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/226249 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University 118 Bifa Ji and Qizhi: Interpretations for Muqi and Contemporary Chinese Art David Adam Brubaker Abstract Jing Hao’s Bifa Ji (Notes on Brushwork) applies the principle of qiyun (氣韻 rhythmic vitality) to the painting of natural scenery. The usefulness of this text about shanshui (山水) aesthetics for contemporary artists and designers is an open question in China today. For Jing Hao, a painting exhibits qiyun by displaying an image that is authentic (眞 zhen), and an authentic image is alive and true to the vitality of nature after the artist passes qi (氣 spirit) through zhi (質 substance). The image manifesting qi and zhi differs from all images that represent nature in terms of human perceptual experience of forms, patterns, objects, motions or material processes. To uphold Jing Hao’s aesthetic for artists and audiences today, I offer a comparative aesthetics that translates zhi in terms of Merleau-Ponty’s language for the first-dimension of the “surface of the visible” beheld by the painter. To build a case for translating Jing Hao’s shanshui aesthetics in this way, I consider accounts that Stephen Owen and Mattias Obert offer for Bifa Ji. By amplifying Jing Hao with novel language from Merleau- Ponty, I conclude that shanshui painting is about a direct personal acquaintance and uniqueness of corporal union with nature, for which analytic and pragmatist philosophies of art have no language.