Introduction 1 I Conceive of the Inner Court As a Group of People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenth-Century Painting Before Song Taizong's Reign

Tenth-Century Painting before Song Taizong’s Reign: A Macrohistorical View Jonathan Hay 1 285 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND 2 longue durée artistic 3 Formats 286 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN Tangchao minghua lu 4 5 It 6 287 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND 7 The Handscroll Lady Guoguo on a Spring Outing Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk Pasturing Horses Palace Ban- quet Lofty Scholars Female Transcendents in the Lang Gar- 288 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN den Nymph of the Luo River8 9 10 Oxen 11 Examining Books 12 13 Along the River at First Snow 14 15 Waiting for the Ferry 16 The Hanging Scroll 17 18 19 289 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND Sparrows and Flowers of the Four Seasons Spring MountainsAutumn Mountains 20 The Feng and Shan 21 tuzhou 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 290 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN 29 30 31 32 Blue Magpie and Thorny Shrubs Xiaoyi Stealing the Lanting Scroll 33 291 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND 34 35 36 Screens 37 38 The Lofty Scholar Liang Boluan 39 Autumn Mountains at Dusk 292 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN 40Layered Mountains and Dense Forests41 Reading the Stele by Pitted Rocks 42 It has Court Ladies Pinning Flowers in Their Hair 43 44 The Emperor Minghuang’s Journey to Shu River Boats and a Riverside Mansion 45 46 47tuzhang 48 Villagers Celebrating the Dragonboat Festival 49 Travelers in Snow-Covered Mountains and 50 . -

A Brief Analysis of the Visual Language Features of Chinese Ink and Wash Landscape Paintings

2021 4th International Conference on Arts, Linguistics, Literature and Humanities (ICALLH 2021) A Brief Analysis of the Visual Language Features of Chinese Ink and Wash Landscape Paintings Lai Yingqin Dept of Ceramic Art, Quanzhou Vocational College of Arts and Crafts, Quanzhou, 362500, China Keywords: Chinese painting, Ink, Landscape, Visual language Abstract: Ink and wash can be connected into lines by brushing, rubbing, drawing, drawing, and drawing on rice paper, and the points can be connected into lines, and the lines can be gathered into surfaces, and the surface can be transformed into a space with both virtual and real. Ink and wash landscape paintings are shaped in this way. A visual language that speaks less and more. It can describe both the real scene that people see, and the illusory scene that people see. That's it, the visual language of ink and wash landscape painting can be brilliant and intoxicating. It is based on the specific performance of stippling, which gives people a visual impact, and is laid out in the invisible surroundings, making people think about the scenery. 1. Introduction Since entering the modern industrialized society, due to the profound influence of modern industrialization culture, especially machine aesthetics, art design culture is in the ascendant, in the field of visual design, people can see images everywhere, such as “font design, logo design, illustration” Design, layout design, advertising design, film and television design, packaging design, book binding design, CIS design, display design, graphic design, etc.” (1), all have entered the field of vision of people, and even some product designs (including industrial product design, The content and form of home design, clothing design) and space design (including indoor and outdoor design, display design, architectural design, garden design and urban design) have also entered people’s vision as visual content. -

In the Liaoning Provincial Museum. by Contrast, Riverbank Stands Virtu

133 Summer Mountains (Qi, fig. 3), in the Liaoning Provincial Museum.14 By contrast, Riverbank stands virtu Shih Positioning ally alone, and lacks an auxiliary body of works that will support the claim to authorship by Dong Yuan. Riverbank Therefore, even if the above analysis safely locates the painting's date in the tenth century, its authorship still appears uncertain. In attempting a thematic approach in our inquiry into the connection of this work with Dong Yuan, we should not limit ourselves solely to Dong Yuan attributions, but instead must expand our focus to include the larger context of works by Southern Tang court painters. The paintings we have already discussed in connection with the dating of Riverbank, namely, First Snow along the River and The Lofty Scholar Liang Boluan, are both by Southern Tang court painters. They are, as is Riverbank, depictions of scenes oflife in southeast China. Water is depicted in these paintings, but in addition, detailed wave patterns model the river's surface. Lofty Scholar (fig. 6) displays an especially close similarity with Riverbank. Both paintings depict reclusive life in architectural settings within a distinct space along a riverbank, a feature rarely found in early landscape painting from north China. Lofty Scholar places narrative content, the story of Lady Meng Guang and her husband Liang Hong of the Eastern Han, within a landscape setting of fantastic rock formations. 15 Riverbank's rock formations are also fantastic in shape, and similarly lack the smoothness of Wintry Groves and Layered Banks. It is also rich in its depiction of scenes of human activity, featuring such details as a herdboy on a water buffalo heading home, a kitchen where women are preparing food, and the lord of the manor relaxing in a pavilion at the river's edge, accom panied by his wife and child. -

Zen As a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries

Zen as a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries by Meng Ying Fan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Meng Ying Fan 2020 Zen as a Creative Agency: Picturing Landscape in China and Japan from the Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries Meng Ying Fan Master of Arts Department of East Asia Studies University of Toronto 2020 Abstract This essay explores the impact of Chan/Zen on the art of landscape painting in China and Japan via literary/visual materials from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. By rethinking the aesthetic significance of “Zen painting” beyond the art and literary genres, this essay investigates how the Chan/Zen culture transformed the aesthetic attitudes and technical manifestations of picturing the landscapes, which are related to the philosophical thinking in mind. Furthermore, this essay emphasizes the problems of the “pattern” in Muromachi landscape painting to criticize the arguments made by D.T. Suzuki and his colleagues in the field of Zen and Japanese art culture. Finally, this essay studies the cultural interaction of Zen painting between China and Japan, taking the traveling landscape images of Eight Views of Xiaoxiang by Muqi and Yujian from China to Japan as a case. By comparing the different opinions about the artists in the two regions, this essay decodes the universality and localizations of the images of Chan/Zen. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratefulness to Professor Johanna Liu, my supervisor and mentor, whose expertise in Chinese aesthetics and art theories has led me to pursue my MA in East Asian studies. -

![[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1753/re-viewing-the-chinese-landscape-imaging-the-body-in-visible-in-shanshuihua-1061753.webp)

[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫

[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫 Lim Chye Hong 林彩鳳 A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chinese Studies School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Australia abstract This thesis, titled '[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫,' examines shanshuihua as a 'theoretical object' through the intervention of the present. In doing so, the study uses the body as an emblem for going beyond the surface appearance of a shanshuihua. This new strategy for interpreting shanshuihua proposes a 'Chinese' way of situating bodily consciousness. Thus, this study is not about shanshuihua in a general sense. Instead, it focuses on the emergence and codification of shanshuihua in the tenth and eleventh centuries with particular emphasis on the cultural construction of landscape via the agency of the body. On one level the thesis is a comprehensive study of the ideas of the body in shanshuihua, and on another it is a review of shanshuihua through situating bodily consciousness. The approach is not an abstract search for meaning but, rather, is empirically anchored within a heuristic and phenomenological framework. This framework utilises primary and secondary sources on art history and theory, sinology, medical and intellectual history, ii Chinese philosophy, phenomenology, human geography, cultural studies, and selected landscape texts. This study argues that shanshuihua needs to be understood and read not just as an image but also as a creative transformative process that is inevitably bound up with the body. -

Song Dynasty Traditional Landscape Paintings a Two-Week Lesson Plan Unit (Based on a 55 Min Class Period)

East Asian Lesson Plans By Rebecca R. Pope 3/7/04 [email protected] China Song Dynasty Traditional Landscape Paintings A two-week lesson plan unit (based on a 55 min class period) Purpose: To expose High School Painting Students (10 –12), to Chinese Culture and Chinese traditional landscape painting 1. How cultural differences affect painting processes? 2. What tools and techniques? 3. How is the painting created and laid out? Rationale: Teach new ideas and art concepts, while reinforcing others, through a Chinese cultural tradition. Materials: 1. Copy of the book, The Way of Chinese Painting: Its Ideas and Techniques. 2. Sze, Mai-Mai. The Way of Chinese Painting: Its Ideas and Techniques. New York, New York. Vintage Books a Division of Random House. 1959. Second Publishing. With selections from the Seventeenth-Century Mustard Seed Garden Manual. 3. Copy of the book Principals of Chinese Painting. Rowley, George. Principals of Chinese Painting. Revised Edition. Princeton, New Jersey. Princeton University Press. 1970. First Paperback Printing. (A more up to date resource could be, how to painting guide book like “Dreaming the Southern Song Landscape: The Power of Illusion in Chinese Painting”, Brill Academic Publishers, Incorporated; or “Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent”, Harvard University Press. Many more could found on booksellers websites.) 4. A guest speaker who is knowledgeable on contemporary Chinese Culture. (I am fortunate to have a colleague, the school librarian, Karen Wallis, who has had two extensive working trips to China setting up a library.) 5. “KWL” Worksheet- • K -representing what students already know about China and Chinese landscape painting • W- representing what they would like to learn • L- representing what they learned (note taking) 1. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 469 Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2020) "Evaluating Painters All Over the Country" Guo Xi and His Landscape Painting Min Ma1,* 1Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Styled Chunfu, Guo Xi was a native of Wenxian County. In the beginning, he learned from the methods of Li Cheng, yet he was rather good at expressing his own feelings, thus becoming adept at surpassing his master and creating a main school of the royal court landscape painting in the Northern Song Dynasty whose influence had lasted to later ages. Linquan Gaozhi Ji, Guo Xi's well-known theory on landscape painting, was a book emerged after the art of landscape painting in the became highly mature in the Northern Song Dynasty, which was an unprecedented peak in landscape painting and a rich treasure house in the history of landscape painting. Keywords: Guo Xi, Linquan Gaozhi, landscape painting Linquan Gaozhi Ji wrote by Guo Xi and his son I. INTRODUCTION Guo Si in 1080 was a classic book on landscape Great progress had been made in the creation of painting as the art of landscape painting became highly panoramic landscape paintings in China during the mature in the Northern Song Dynasty. The book was Northern Song Dynasty, after the innovations of Jing written in the late Northern Song Dynasty, when the art Hao, Guan Tong, Dong Yuan and Ju Ran, when a of landscape painting in China had already entered a number of influential landscape painters and exquisite relatively mature stage. -

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's Name Dates R Pinyin Romanization of Artist's

CHINESE ARTISTS Pinyin-Wade-Giles Concordance Wade-Giles Romanization of Artist's name ❍ Dates ❍ Pinyin Romanization of Artist's name Artists are listed alphabetically by Wade-Giles. This list is not comprehensive; it reflects the catalogue of visual resource materials offered by AAPD. Searches are possible in either form of Romanization. To search for a specific artist, use the find mode (under Edit) from the pull-down menu. Lady Ai-lien ❍ (late 19th c.) ❍ Lady Ailian Cha Shih-piao ❍ (1615-1698) ❍ Zha Shibiao Chai Ta-K'un ❍ (d.1804) ❍ Zhai Dakun Chan Ching-feng ❍ (1520-1602) ❍ Zhan Jingfeng Chang Feng ❍ (active ca.1636-1662) ❍ Zhang Feng Chang Feng-i ❍ (1527-1613) ❍ Zhang Fengyi Chang Fu ❍ (1546-1631) ❍ Zhang Fu Chang Jui-t'u ❍ (1570-1641) ❍ Zhang Ruitu Chang Jo-ai ❍ (1713-1746) ❍ Zhang Ruoai Chang Jo-ch'eng ❍ (1722-1770) ❍ Zhang Ruocheng Chang Ning ❍ (1427-ca.1495) ❍ Zhang Ning Chang P'ei-tun ❍ (1772-1842) ❍ Zhang Peitun Chang Pi ❍ (1425-1487) ❍ Zhang Bi Chang Ta-ch'ien [Chang Dai-chien] ❍ (1899-1983) ❍ Zhang Daqian Chang Tao-wu ❍ (active late 18th c.) ❍ Zhang Daowu Chang Wu ❍ (active ca.1360) ❍ Zhang Wu Chang Yü [Chang T'ien-yu] ❍ (1283-1350, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu [Zhang Tianyu] Chang Yü ❍ (1333-1385, Yüan Dynasty) ❍ Zhang Yu Chang Yu ❍ (active 15th c., Ming Dynasty) ❍ Zhang You Chang Yü-ts'ai ❍ (died 1316) ❍ Zhang Yucai Chao Chung ❍ (active 2nd half 14th c.) ❍ Zhao Zhong Chao Kuang-fu ❍ (active ca. 960-975) ❍ Zhao Guangfu Chao Ch'i ❍ (active ca.1488-1505) ❍ Zhao Qi Chao Lin ❍ (14th century) ❍ Zhao Lin Chao Ling-jang [Chao Ta-nien] ❍ (active ca. -

The Poetic Ideas Scroll Attributed to Mi Youren and Sima Huai*

The Poetic Ideas Scroll Attributed to Mi Youren and Sima Huai │ 85 The Poetic Ideas Scroll paintings extant, is one of the best represented painters of the Song dynasty.1Moreover, especially in the eyes of later admirers, his paintings share a uniform subject and style: Attributed to Mi Youren and Sima Huai* cloudy landscapes (yunshan 雲山) rendered largely with blunt strokes, repetitive dots, and wet ink tones. In contrast, Sima Huai is essentially an unknown figure—so unknown, in Peter C. Sturman University of California, Santa Barbara fact, that even his given name, Huai, is not unequivocally established. Poetic Ideas is composed of two separate paintings, neither of which is signed or imprinted with an artist’s seal. Both are landscapes, though of different types: the first Abstract: (unrolling from right to left) presents a scene of distant mountains by a river with dwellings From the time it came to the attention of scholars and connoisseurs in the late Ming dynasty, the and figures (color plate 8)—I refer to this as“the riverside landscape.” The latter is a “small Poetic Ideas scroll attributed to Mi Youren (1074–1151) and Sima Huai (!. twel"h century) has scene” (xiaojing 小景) of more focused perspective, presenting a pair of twisted trees ’ long been considered an important example of Song dynasty literati painting. #e scroll s two backed by a large cliff and a quickly moving stream that empties from a ravine (color plate 9) paintings, each of which is preceded by single poetic lines by Du Fu, o$er a rare window into —I refer to this as “the entwined trees landscape.” The images complement one another the inventive manner in which Song scholar-o%cial painters combined texts with images. -

The Donkey Rider As Icon: Li Cheng and Early Chinese Landscape Painting Author(S): Peter C

The Donkey Rider as Icon: Li Cheng and Early Chinese Landscape Painting Author(s): Peter C. Sturman Source: Artibus Asiae, Vol. 55, No. 1/2 (1995), pp. 43-97 Published by: Artibus Asiae Publishers Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3249762 . Accessed: 05/08/2011 12:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Artibus Asiae Publishers is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus Asiae. http://www.jstor.org PETER C. STURMAN THE DONKEY RIDER AS ICON: LI CHENG AND EARLY CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING* he countryis broken,mountains and rivers With thesefamous words that lamentthe "T remain."'I 1T catastropheof the An LushanRebellion, the poet Du Fu (712-70) reflectedupon a fundamental principle in China:dynasties may come and go, but landscapeis eternal.It is a principleaffirmed with remarkablepower in the paintingsthat emergedfrom the rubbleof Du Fu'sdynasty some two hundredyears later. I speakof the magnificentscrolls of the tenth and eleventhcenturies belonging to the relativelytightly circumscribedtradition from Jing Hao (activeca. 875-925)to Guo Xi (ca. Ooo-9go)known todayas monumentallandscape painting. The landscapeis presentedas timeless. We lose ourselvesin the believabilityof its images,accept them as less the productof humanminds and handsthan as the recordof a greatertruth. -

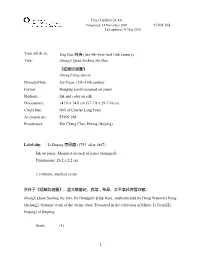

F1909.168 Documentation

Freer Gallery of Art Completed: 14 November 2007 F1909.168 Last updated: 06 May 2010 Trad. attrib. to: Jing Hao 荊浩 (late 9th–first-half 10th century) Title: Zhongli Quan Seeking the Dao 《鍾離訪道圖》 Zhongli fang dao tu Dynasty/Date: Jin-Yuan, 13th–14th century Format: Hanging scroll mounted on panel Medium: Ink and color on silk Dimensions: 147.0 x 74.8 cm (57-7/8 x 29-7/16 in) Credit line: Gift of Charles Lang Freer Accession no.: F1909.168 Provenance: Riu Cheng Chai, Peking (Beijing) Label slip: Li Enqing 李恩慶 (1793–after 1867) Ink on paper. Mounted on back of panel (damaged). Dimensions: 26.2 x 2.2 cm 3 columns, standard script 洪谷子《鍾離訪道圖》。董文敏審定。真蹟,神品。北平李氏寄雲珎藏。 Zhongli Quan Seeking the Dao, by Hongguzi [Jing Hao]. Authenticated by Dong Wenmin [Dong Qichang]. Genuine work of the divine class. Treasured in the collection of Mister Li Jiyun [Li Enqing] of Beiping. Seals: (1) 1 Freer Gallery of Art Completed: 14 November 2007 F1909.168 Last updated: 06 May 2010 Qing『慶』(square relief) Painting: Artist inscription: none Other inscriptions: none Colophon description: Eight (8) colophons written on five lengths of former mounting silk, champagne-color with dragon-and-clouds motif, remounted on back of panel 1a. Former right-side mounting silk. Two joined lengths. Overall dimensions: 94.5 x 11.8 cm. Top length: Dimensions: 35.5 x 11.8 cm Colophon 1, Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555–1636) ink on light-brown silk, mounted as inset 1b. Bottom length: Dimensions: 59 x 11.8 cm Colophon 5, Se Daoren 嗇道人 (unidentified; late 19th–early 20th century) written directly on mounting silk; plus two (2) collector seals of Liang Qingbiao 梁清標 (1620–1691) on light-brown mounting silk (same as Colophon 1), mounted as inset 2. -

Art As History: Calligraphy and Painting As

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. List of Illustrations Illustrations are indexed according to three categories: Sculpture and Reliefs; Calligraphy; and Painting and Graphic Illustrations. These categories are further subdivided by Archaeological and Temple Sites and then by Artist. sculpture and reliefs archaeological and temple sites Binglingsi, Yongjing, Gansu province. Buddha from Cave 169, dated 420. Sculpture and wall painting. 123 Liu Sheng, tomb of, 2nd century bce. Mancheng, Hebei province. Censer in the Form of a Cosmic Mountain. Bronze with gold. Hebei Provincial Museum. 71 Longmen, Luoyang, Henan province Plinth of circumambulating monks, Kanjing Si, early 7th century. Limestone. 225 Seated Buddha from Guyang Cave, ca. 500. Limestone. 223 Seated Buddha with attendants, 680. View of the main wall in Wanfodong. 157 Vairocana Buddha, Fengxian Si, dated 675. Limestone. 153 Longxing Monastery, Northern Qi, 6th century. Qingzhou, Shandong province. Śākyamuni Buddha. Stone with traces of gilt and polychrome pigments. Qingzhou Municipal Museum, Shandong. 85 Loulan, Xinjiang province. Manuscript, early 4th century. Ink on paper. 27 Qinshihuangdi, tomb of. Xi’an, Shaanxi province. Qin dynasty, 3rd century bce. General. Terracotta. Museum of Terracotta Warriors and Horses. 125 Ruruta in the Austral Isles, Polynesia. The Fractal God, A’a, before 1821. Wood. The British Museum. 33 Tianlongshan, Taiyuan, Shanxi province. Buddha, 8th century. West niche of Cave 16. Stone. 159 Wanfo Si, Chengdu, Sichuan province Buddha, dated 529. Stone. Sichuan Provincial Museum. 145 Buddha, dated 537. Stone.