Madonna and Child with God the Father Blessing and Angels C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol 3 Issue 2 Artistic Impression

Vol. 3, Issue 2 February, 2021 Burlington Artists League A Word from the President Dear BAL members, Welcome to the February edition of our newsletter. Our previous editor has resigned and until we can find another one, Angela Bostek is serving as our interim editor, taking on yet another responsibility. Our profound thanks, Angela. The month of February conjures up associations with the bleak mid-winter season. On the other hand, it anticipates the arrival of spring, especially if the ground-hog’s prognostications are correct. For us, it means the Small Art Contest. I am pleased that the contest this year has been a success. The entries were as fine as ever and my thanks to all participants and congratulations to the winners! Unfortunately, due to Covid restrictions, we could not have our usual reception to honor the winners. However, as usual, all entries will be on display for the month of February. Please take an hour or so during the month to drop by the gallery to admire all the art submitted for the contest. It’s quite impressive. Now we look forward to the next competition in April. Further information will be forthcoming, watch your email. We hope you will join us for our monthly business meeting by way of Zoom on Thursday, February 18, at 3 p.m. One of the main agenda items will be a discussion of possibly adding a competition at the end of the summer and your input is valuable. In the meantime, stay warm and safe. Jane ********* FEBRUARY CALENDAR OF EVENTS 1st – 28th 14th 18th Jan 22 – Feb 18 Feb. -

Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: Rinascita

Niccolo’ Machiavelli (1469‐1527) • Political career (1498‐1512) • Official in Florentine Republic – Diplomat: observes Cesare Borgia – Organizes Florentine militia and military campaign against Pisa – Deposed when Medici return in 1512 – Suspected of treason he is tortured; retired to his estate Major Works: The Prince (1513): advice to Prince, how to obtain and maintain power Discourses on Livy (1517): Admiration of Roman republic and comparisons with his own time – Ability to channel civil strife into effective government – Admiration of religion of the Romans and its political consequences – Criticism of Papacy in Italy – Revisionism of Augustinian Christian paradigm Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: rinascita • Early Renaissance: 1420‐1500c • ‐‐1420: return of papacy (Martin V) to Rome from Avignon • High Renaissance: 1500‐1520/1527 • ‐‐ 1503: Ascension of Julius II as Pope; arrival of Bramante, Raphael and Michelangelo; 1513: Leo X • ‐‐1520: Death of Raphael; 1527 Sack of Rome • Late Renaissance (Mannerism): 1520/27‐1600 • ‐‐1563: Last session of Council of Trent on sacred images Artistic Renaissance in Rome • Patronage of popes and cardinals of humanists and artists from Florence and central/northern Italy • Focus in painting shifts from a theocentric symbolism to a humanistic realism • The recuperation of classical forms (going “ad fontes”) ‐‐Study of classical architecture and statuary; recovery of texts Vitruvius’ De architectura (1414—Poggio Bracciolini) • The application of mathematics to art/architecture and the elaboration of single point perspective –Filippo Brunellschi 1414 (develops rules of mathematical perspective) –L. B. Alberti‐‐ Della pittura (1432); De re aedificatoria (1452) • Changing status of the artist from an artisan (mechanical arts) to intellectual (liberal arts; math and theory); sense of individual genius –Paragon of the arts: painting vs. -

"Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 "Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth Aaron Hubbell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hubbell, Aaron, ""Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4408. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THINGS NOT SEEN" IN THE FRESCOES OF GIOTTO: AN ANALYSIS OF ILLUSORY AND SPIRITUAL DEPTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and the School of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in The School of Art by Aaron T. Hubbell B.F.A., Nicholls State University, 2011 May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Elena Sifford, of the College of Art and Design for her continuous support and encouragement throughout my research and writing on this project. My gratitude also extends to Dr. Darius Spieth and Dr. Maribel Dietz as the additional readers of my thesis and for their valuable comments and input. -

Thoughts About Paintings Conservation This Page Intentionally Left Blank Personal Viewpoints

PERSONAL VIEWPOINTS Thoughts about Paintings Conservation This page intentionally left blank Personal Viewpoints Thoughts about Paintings Conservation A Seminar Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 EDITED BY Mark Leonard THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES & 2003 J- Paul Getty Trust THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Timothy P. Whalen, Director Los Angeles, CA 90049-1682 Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, www.getty.edu Field Projects and Science Christopher Hudson, Publisher The Getty Conservation Institute works interna- Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief tionally to advance conservation and to enhance Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Manuscript Editor and encourage the preservation and understanding Jeffrey Cohen, Designer of the visual arts in all of their dimensions— Elizabeth Chapín Kahn, Production Coordinator objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas scientific research; education and training; field Printed in Hong Kong by Imago projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. Library of Congress In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed Cataloging-in-Publication Data to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation Personal viewpoints : thoughts about paintings practice. conservation : a seminar organized by The J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 /volume editor, Mark Leonard, p. -

Daddi, Bernardo Also Known As Daddo, Bernardo Di Active by 1320, Died Probably 1348

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Daddi, Bernardo Also known as Daddo, Bernardo di active by 1320, died probably 1348 BIOGRAPHY Son of Daddo di Simone, Bernardo is recorded for the first time in the registers of the Arte dei Medici e Speziali when he enrolled in the guild (which also included artists) between 1312 and 1320.[1] By this date he must have been a firmly established painter, as the reconstruction of his oeuvre also suggests; presumably, he had been born by the last decade of the thirteenth century, if not earlier. His first securely dated work is the signed triptych in the Uffizi, Florence; its inscription contains not only the artist’s name but also the year 1328. Recent studies, however, have assigned various works, also of large dimensions, to previous years, such as the cycle of frescoes in the chapel of the Pulci and Berardi families in Santa Croce in Florence; the polyptych of San Martino at Lucarelli (Siena), now in the New Orleans Museum of Art; and the polyptych divided among the Galleria Nazionale in Parma, the Museo Lia in La Spezia, and a private collection.[2] Although perhaps trained in the circle of painters such as Lippo di Benivieni or the Master of San Martino alla Palma,[3] in the second or the early third decade of the fourteenth century Bernardo worked in close contact with Giotto’s shop (executing for the church of Santa Croce, then the preserve of the pupils and followers of the great master, not only the abovementioned frescoes but also possibly the Parma–La Spezia polyptych).[4] During the fourth and fifth decades of the century, Daddi’s shop seems to have produced by preference numerous small but precious panels destined for private devotion. -

L'arte Del Primo Rinascimento

1401 Concorso per la Seconda Porta del Battistero a Firenze. Inizio del Rinascimento 1434 A Firenze è fondata la L’ARTE Signoria dei Medici 1418-36 Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore di 1425-52 Brunelleschi Porta del Paradiso di Ghiberti 1438-40 DEL PRIMO Battaglia di San Romano di Paolo Uccello 1427 Trinità di Masaccio in RINASCIMENTO Santa Maria Novella dal 1400 al 1500 I TEMPI E I LUOGHI Tra il XIV e il XV secolo, i Comuni medievali si trasformarono in Signorie, forme di governo capaci di rispondere all’esigenza di governi più stabili e più forti. In Italia prevalsero cinque Stati i capolavori di grande importanza: Firenze (che formalmente mantenne architettura gli ordinamenti repubblicani e comunali), il Ducato di Milano, ● La Cupola di Santa Maria del Fiore di Brunelleschi la Repubblica di Venezia (governata da una oligarchia ● La facciata di Santa Maria Novella mercantile), lo Stato della Chiesa (con Roma sede della a Firenze Curia papale) e il regno di Napoli a Sud. arti visive ● Il David di Donatello A Firenze, nel 1434, il potere si concentrò nelle mani della ● La Porta del Paradiso di Ghiberti famiglia Medici. Cosimo dei Medici, detto il Vecchio, ● La Trinità di Masaccio in Santa Maria Novella ricchissimo banchiere e commerciante, divenne, di fatto, il ● La Battaglia di San Romano padrone incontrastato della città. Anche negli altri piccoli di Paolo Uccello Stati italiani, come il Ducato di Savoia, la Repubblica di ● La Flagellazione di Piero della Francesca Genova, il Ducato di Urbino, le Signorie di Mantova, Ferrara, ● Il Cristo morto di Mantegna Modena e Reggio, le sorti si legarono ai nomi di alcune grandi famiglie. -

Imagines-Number-2-2018-August

Imagines è pubblicata a Firenze dalle Gallerie degli Uffizi Direttore responsabile Eike D. Schmidt Redazione Dipartimento Informatica e Strategie Digitali Coordinatore Gianluca Ciccardi Coordinatore delle iniziative scientifiche delle Gallerie degli Uffizi Fabrizio Paolucci Hanno lavorato a questo numero Andrea Biotti, Patrizia Naldini, Marianna Petricelli Traduzioni: Eurotrad con la supervisione di Giovanna Pecorilla ISSN n. 2533-2015 2 august 2018 index n. 2 (2018, August) 6 EIKE SCHMIDT Digital reflexions 10 SILVIA MASCALCHI School/Work programmes at the Uffizi Galleries. Diary of an experience in progress 20 SIMONE ROVIDA When Art Takes Centre Stage. Uffizi Live and live performance arts as a means to capitalise on museum resources 38 ELVIRA ALTIERO, FEDERICA CAPPELLI, LUCIA LO STIMOLO, GIANLUCA MATARRELLI An online database for the conservation and study of the Uffizi ancient sculptures 52 ALESSANDRO MUSCILLO The forgotten Grand Duke. The series of Medici-Lorraine busts and their commendation in the so-called Antiricetto of the Gallery of Statues and Paintings 84 ADELINA MODESTI Maestra Elisabetta Sirani, “Virtuosa del Pennello” 98 CARLA BASAGNI PABLO LÓPEZ MARCOS Traces of the “Museo Firenze com’era in the Uffizi: the archive of Piero Aranguren (Prato 1911- Florence 1988), donated to the Library catalog 107 FABRIZIO PAOLUCCI ROMAN ART II SEC. D. C., Sleepimg Ariadne 118 VINCENZO SALADINO ROMAN ART, Apoxyomenos (athlete with a Scraper) 123 DANIELA PARENTI Spinello Aretino, Christ Blessing Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, Crocifixion 132 ELVIRA ALTIERO Niccolò di Buonaccorso, Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple n.2 | august 2018 Eike Schmidt DIGITAL REFLEXIONS 6 n Abbas Kiarostami’s film Shirin (2008), sing questions of guilt and responsibility for an hour and a half we see women – would have been superimposed upon Iin a theatre in Iran watching a fictio- its famous first half, the action-packed nal movie based on the tragic and twi- Nibelungenlied (Song of the Nibelungs). -

WISHBOOK-2019.Pdf

FRONT COVER Crivelli Madonna with Child - Carlo Crivelli XV - XVI Century Art Department pages 136 - 139 Contents 3 4 Letter from the President of the Vatican City State 94 Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints 6 Letter from the Director of the Vatican Museums 98 Enthroned Madonna and Child Letter from the International Director of the 102 Saints Paola and Eustochium 8 Patrons of the Arts 106 Stories of the Passion of Christ 110 Icons from the Tower of Pope John XXIII 10 BRAMANTE COURTYARD Long-term Project Report 126 XV – XVI CENTURY ART 16 CHRISTIAN ANTIQUITIES 128 Tryptich of the Madonna and Child with Saints 18 Drawn Replicas of Christian Catacombs Paintings 132 Apse of the Church of San Pellegrino 22 GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITIES 136 Crivelli Madonna with Child 24 Chiaramonti Gallery Wall XlV 140 Madonna and Child with Annunciation and Saints 30 Ostia Collection: Eleven Figurative Artifacts 144 XVII – XVIII CENTURY ART AND TAPESTRIES Ostia Collection: Two Hundred and Eighty-three 34 Household Artifacts 146 Noli Me Tangere Tapestry 38 Statue of an Old Fisherman 150 Plaster Cast of the Bust of Pope Pius VII 42 Polychrome Mosaic with Geometric Pattern 154 Two Works from the Workshop of Canova 162 Portrait of Pope Clement IX 46 GREGORIAN ETRUSCAN ANTIQUITIES 166 Embroidery Drawings for Papal Vestments 48 Krater, Kylixes and Perfume Jars 52 Gold Necklaces from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb 170 XIX CENTURY AND CONTEMPORARY ART 56 Astarita Collection: Thirty-three Figurative Vases 172 Clair de Lune 60 Ceremonial Clasp from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb 176 Model of Piazza Pius XII 64 Amphora and a Hundred Fragments of Bucchero 180 HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS 68 DECORATIVE ARTS 182 Two Jousting Shields 70 Rare Liturgical Objects 186 Drawing of the Pontifical Army Tabella 76 Tunic of “St. -

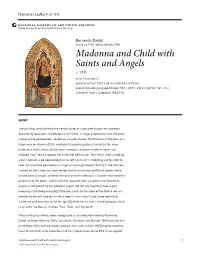

Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Bernardo Daddi active by 1320, died probably 1348 Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels c. 1345 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.2 x 24.2 cm (19 3/4 x 9 1/2 in.) overall (including engaged frame): 57.1 × 30.5 × 2.6 cm (22 1/2 × 12 × 1 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1952.5.61 ENTRY The painting, which formed the central panel of a portable triptych for domestic devotion,[1] represents the Madonna and Child, in larger proportions than the other figures in the composition, seated on a raised throne. The throne is in the form of a tabernacle or ciborium;[2] its crocketed triangular gable is framed by the inner trefoil arch of the panel, and its inner canopy is decorated with an azure star- studded “sky.” Mary supports her child with both hands. The Christ child is holding a fruit, perhaps a pomegranate,[3] in his left hand and is stretching out his right to take the small bird perched on a finger of the angel closest to him.[4] The throne is flanked on both sides by a red seraph and an azure cherub [5] and, below these, by two pairs of angels, of which the one to the far left plays a shawm—the medieval precursor of the oboe—and that on the opposite side a psaltery; the concert of angels is completed by the portative organ and the viol played by two angels kneeling in the foreground.[6] Of the four saints to the sides of the throne we can identify, to the left, Apollonia, with a tooth in her hand,[7] and, more doubtfully, -

Circolo Culturale Masolino Da Panicale

Masolino da Panicale Tommaso di Cristoforo FiniFini, noto come Masolino da PanicaPanicalPanica llleeee, nasce a San Giovanni Valdarno (Arezzo) nel 1383 ma dei suoi primi quarant’anni di vita non si sa praticamente nulla anche se si parla di un apprendistato presso la bottega di Gherardo Stamina e di una successiva in quella di Lorenzo Ghiberti nei primi anni del Quattrocento. Le prime notizie certe sono del 1422 quando il pittore prende in affitto una casa a Firenze iscrivendosi, l’anno successivo, alla corporazione dell’Arte dei Medici e Speziali che includeva anche l’arte pittorica. Per molto tempo si pensò a Masolino come maestro di Masaccio, ipotesi che venne poi scartata preferendo a questa quella di “collaboratore professionale”, un intesa che portò i due alla realizzazione di diverse opere a “quattro mani”. La prima opera conosciuta del pittore è “Madonna con Bambino” datata 1423, probabilmente ricordo di un matrimonio tra le famiglie Boni e Carnesecchi come si rileva, alla base del dipinto, dagli stemmi delle due famiglie, opera, in parte legata agli schemi tardo gotici, oggi conservata al Kunsthalle di Brema. Dello stesso periodo, ma decisamente legato al gotico, è la “Madonna dell’Umiltà” oggi conservata alla Galleria degli Uffizi di Firenze. Nel 1424 Masolino lavora ad Empoli, probabilmente assistito da Francesco d’Antonio, artista minore uscito dall'orbita di Lorenzo Monaco, eseguendo un vasto ciclo di affreschi nella Chiesa di Santo Stefano, dei quali però restano solo pochi frammenti quali “Sant'Ivo e i pupilli” e “Vergine col Bambino”. Nel Battistero della Collegiata affrescò inoltre un “Cristo in pietà”, oggi nel Museo della Collegiata di Sant’Andrea. -

ARTH206-Giorgio Vasari-Lives of the Most Emminent

Selections from Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors & Architects Giorgio Vasari, Translated by Gaston Du C. De Vere (1912-14) Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 1 of 199 LIVES OF THE MOST EMINENT PAINTERS SCULPTORS & ARCHITECTS 1912 BY GIORGIO VASARI: NEWLY TRANSLATED BY GASTON Du C. DE VERE. WITH FIVE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS: IN TEN VOLUMES LONDON: MACMILLAN AND CO. LD. & THE MEDICI SOCIETY, LD. 1912-14 CONTENTS Volume 1 3 Dedications to the Cosimo Medici 4 The Author’s Preface to the Whole Work 7 Giovanni Cimabue 19 Niccola and Giovanni of Pisa 31 Giotto 50 Ambrogio Lorenzetti 78 Volume 2 83 Duccio 84 Paolo Ucello 90 Lorenzo Ghiberti 100 Masolino Da Panicale 121 Masaccio 126 Filippo Brunelleschi 136 Donato [Donatello] 178 Volume 1 Footnotes 198 Volume 2 Footnotes 199 Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 2 of 199 VOLUME I Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 3 of 199 DEDICATIONS TO COSIMO DE' MEDICI TO THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND MOST EXCELLENT SIGNOR COSIMO DE' MEDICI, DUKE OF FLORENCE AND SIENA MY MOST HONOURED LORD, Behold, seventeen years since I first presented to your most Illustrious Excellency the Lives, sketched so to speak, of the most famous painters, sculptors and architects, they come before you again, not indeed wholly finished, but so much changed from what they were and in such wise adorned and enriched with innumerable works, whereof up to that time I had been able to gain no further knowledge, that from my endeavour and in so far as in me lies nothing more can be looked for in them. -

Vasari: a Translation from Die Kunstliteratur (1924)

Julius von Schlosser on Vasari: a translation from Die Kunstliteratur (1924) Karl Johns - Julius Schlosser and the location of Vasari When Thomas Mann was composing Doktor Faustus and decided to have the devil make an appearance at the precise center of the manuscript, he was applying his literary irony to a phenomenon in which he had himself participated, which affected his life directly, and threatened those of his wife and children.1 When Julius Schlosser made Giorgio Vasari the isolated subject of Book Five of his Kunstliteratur, he was also describing a certain development in idiosyncratic literary terms and placing a figure at the center who could not ultimately be applauded according to the terms of his ‘Kunstliteratur’. Unlike the world of Adrian Leverkühn, Schlosser, who was felicitously described in a 1939 obituary as ‘an anachronism in the very best sense of the term’, had developed his concept of the literature of art ‘Kunstliteratur’ independently of the trends of the time. Indeed, his most ambitious essays had included a systematic refutation of the flawed premises of various types of scholarly writings about earlier art then flourishing. Formalism and undue abstraction were then exciting popular interest and drawing unusual numbers of auditors into academic lecture halls. The burgeoning literature of dissertations was being roundly criticized. In this period of emotional nationalism and rising fascism, his development of the concept of ‘Kunstliteratur’ served to stress the importance of objectivity in historical scholarship independently of anything one might feel. To create such a footing it would be necessary in his ‘classic’ book to clarify the entire emergence of the academic discipline of the history of art.