The Crucifixion C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

'…Con Uno Inbasamento Et Ornamento Alto': the Rhetoric of the Pedestal C. 1430-1550

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Wright, A; (2011) '... con uno inbasamento et ornamento alto': The rhetoric of the pedestal c. 1430- 1550. Art History, 34 (1) pp. 8-53. 10.1111/j.1467-8365.2010.00798.x. Downloaded from UCL Discovery: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1399808/. ARTICLE ‘…con uno inbasamento et ornamento alto’: the rhetoric of the pedestal c. 1430-1550. Alison Wright School of Arts and Social Sciences, University College London When, in 1504, the Florentine painter Cosimo Rosselli gave his opinion on the best situation for Michelangelo’s colossal David, he suggested it be placed by the cathedral and raised up on a high pedestal (‘uno inbasamento et ornamento alto’).1 Rosselli imagined the marble statue dominating the corner of the entrance steps, just to the right of the façade. Sandro Botticelli lent his backing to Rosselli’s view with the argument that the sculpture would here be best visible to passers-by. Against both these painters, a goldsmith, Andrea Riccio - almost certainly a local Florentine and not the Paduan bronze sculptor - proposed a position in the courtyard of the town hall, the Palazzo della Signoria.2 Here, he claims, the sculpture would be better protected and passers-by would go to see it rather than, as he vividly puts it, ‘the figure should come and see us.’3 Differences of opinion expressed in this unusually well documented debate centred above all around questions of visibility, concern for the statue’s material preservation as well as the representational and ritual needs of the Florentine government.4 Tangentially, the debate also highlighted the crucial role of the pedestal and its physical and ritual situation in mediating the encounter with sculpture. -

Passaporto Per Denaro E Bellezza Passport to Money and Beauty Passaporto Per Denaro E Bellezza

PASSAPORTO PER DENARO E BELLEZZA PASSPORT TO MONEY AND BEAUTY PASSAPORTO PER DENARO E BELLEZZA Le banche rappresentano una parte talmente importante del mondo moderno che è impossibile immaginarlo senza di esse; tuttavia sono un’invenzione relativamente recente, nata dalla crescente mobilità e dal commercio sviluppatosi a partire dalla fne del XII secolo. Le grandi famiglie toscane di mercanti-banchieri – Bardi, Peruzzi e, molto più tardi i Medici – hanno lasciato durevoli testimonianze del proprio talento in campo fnanziario, non solo accumulando enormi fortune, ma traducendole in opere d’arte che sono divenute parte del patrimonio culturale mondiale. La più antica banca al mondo ancora operante – il Monte dei Paschi – fu fondata a Siena nel 1472, solo 25 anni prima dei “roghi delle vanità” del predicatore integralista Savonarola, per i quali i forentini consegnarono per essere bruciate le “cose vane” preziose come gioielli, specchi e opere d’arte possedute. Denaro e Bellezza. I banchieri, Botticelli e il rogo delle vanità non è una mostra su un singolo artista, sebbene si chiuda con molti dipinti di Botticelli e presti particolare attenzione all’infuenza esercitata su di lui da Savonarola. È qualcosa di anche più interessante: una mostra sulla nascita in Toscana del moderno sistema bancario. James M. Bradburne PASSPORT TO MONEY AND BEAUTY Banks are such an important part of the modern world that it is almost impossible to imagine the world without them. Nevertheless, banks are a relatively recent invention, born from increased mobility and growing European trade in the late 12th century. The great Tuscan banking families—the Bardi, the Peruzzi, and of course much later, the Medici—created lasting monuments to their fnancial ingenuity, not only by amassing vast fortunes, but by translating those fortunes into the works of art that have become a part of the world’s cultural heritage. -

"Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2017 "Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth Aaron Hubbell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hubbell, Aaron, ""Things Not Seen" in the Frescoes of Giotto: An Analysis of Illusory and Spiritual Depth" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4408. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THINGS NOT SEEN" IN THE FRESCOES OF GIOTTO: AN ANALYSIS OF ILLUSORY AND SPIRITUAL DEPTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and the School of Art in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in The School of Art by Aaron T. Hubbell B.F.A., Nicholls State University, 2011 May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Elena Sifford, of the College of Art and Design for her continuous support and encouragement throughout my research and writing on this project. My gratitude also extends to Dr. Darius Spieth and Dr. Maribel Dietz as the additional readers of my thesis and for their valuable comments and input. -

THE BERNARD and MARY BERENSON COLLECTION of EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls

THE BERNARD AND MARY BERENSON COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PAINTINGS AT I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls GENERAL INDEX by Bonnie J. Blackburn Page numbers in italics indicate Albrighi, Luigi, 14, 34, 79, 143–44 Altichiero, 588 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum catalogue entries. (Fig. 12.1) Alunno, Niccolò, 34, 59, 87–92, 618 Angelico (Fra), Virgin of Humility Alcanyiç, Miquel, and Starnina altarpiece for San Francesco, Cagli (no. SK-A-3011), 100 A Ascension (New York, (Milan, Brera, no. 504), 87, 91 Bellini, Giovanni, Virgin and Child Abbocatelli, Pentesilea di Guglielmo Metropolitan Museum altarpiece for San Nicolò, Foligno (nos. 3379 and A3287), 118 n. 4 degli, 574 of Art, no. 1876.10; New (Paris, Louvre, no. 53), 87 Bulgarini, Bartolomeo, Virgin of Abbott, Senda, 14, 43 nn. 17 and 41, 44 York, Hispanic Society of Annunciation for Confraternità Humility (no. A 4002), 193, 194 n. 60, 427, 674 n. 6 America, no. A2031), 527 dell’Annunziata, Perugia (Figs. 22.1, 22.2), 195–96 Abercorn, Duke of, 525 n. 3 Alessandro da Caravaggio, 203 (Perugia, Galleria Nazionale Cima da Conegliano (?), Virgin Aberdeen, Art Gallery Alesso di Benozzo and Gherardo dell’Umbria, no. 169), 92 and Child (no. SK–A 1219), Vecchietta, portable triptych del Fora Crucifixion (Claremont, Pomona 208 n. 14 (no. 4571), 607 Annunciation (App. 1), 536, 539 College Museum of Art, Giovanni di Paolo, Crucifixion Abraham, Bishop of Suzdal, 419 n. 2, 735 no. P 61.1.9), 92 n. 11 (no. SK-C-1596), 331 Accarigi family, 244 Alexander VI Borgia, Pope, 509, 576 Crucifixion (Foligno, Palazzo Gossaert, Jan, drawing of Hercules Acciaioli, Lorenzo, Bishop of Arezzo, Alexeivich, Alexei, Grand Duke of Arcivescovile), 90 Kills Eurythion (no. -

Thoughts About Paintings Conservation This Page Intentionally Left Blank Personal Viewpoints

PERSONAL VIEWPOINTS Thoughts about Paintings Conservation This page intentionally left blank Personal Viewpoints Thoughts about Paintings Conservation A Seminar Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 EDITED BY Mark Leonard THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES & 2003 J- Paul Getty Trust THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Timothy P. Whalen, Director Los Angeles, CA 90049-1682 Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, www.getty.edu Field Projects and Science Christopher Hudson, Publisher The Getty Conservation Institute works interna- Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief tionally to advance conservation and to enhance Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Manuscript Editor and encourage the preservation and understanding Jeffrey Cohen, Designer of the visual arts in all of their dimensions— Elizabeth Chapín Kahn, Production Coordinator objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas scientific research; education and training; field Printed in Hong Kong by Imago projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. Library of Congress In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed Cataloging-in-Publication Data to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation Personal viewpoints : thoughts about paintings practice. conservation : a seminar organized by The J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 /volume editor, Mark Leonard, p. -

Daddi, Bernardo Also Known As Daddo, Bernardo Di Active by 1320, Died Probably 1348

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Daddi, Bernardo Also known as Daddo, Bernardo di active by 1320, died probably 1348 BIOGRAPHY Son of Daddo di Simone, Bernardo is recorded for the first time in the registers of the Arte dei Medici e Speziali when he enrolled in the guild (which also included artists) between 1312 and 1320.[1] By this date he must have been a firmly established painter, as the reconstruction of his oeuvre also suggests; presumably, he had been born by the last decade of the thirteenth century, if not earlier. His first securely dated work is the signed triptych in the Uffizi, Florence; its inscription contains not only the artist’s name but also the year 1328. Recent studies, however, have assigned various works, also of large dimensions, to previous years, such as the cycle of frescoes in the chapel of the Pulci and Berardi families in Santa Croce in Florence; the polyptych of San Martino at Lucarelli (Siena), now in the New Orleans Museum of Art; and the polyptych divided among the Galleria Nazionale in Parma, the Museo Lia in La Spezia, and a private collection.[2] Although perhaps trained in the circle of painters such as Lippo di Benivieni or the Master of San Martino alla Palma,[3] in the second or the early third decade of the fourteenth century Bernardo worked in close contact with Giotto’s shop (executing for the church of Santa Croce, then the preserve of the pupils and followers of the great master, not only the abovementioned frescoes but also possibly the Parma–La Spezia polyptych).[4] During the fourth and fifth decades of the century, Daddi’s shop seems to have produced by preference numerous small but precious panels destined for private devotion. -

Sebastiano Del Piombo and His Collaboration with Michelangelo: Distance and Proximity to the Divine in Catholic Reformation Rome

SEBASTIANO DEL PIOMBO AND HIS COLLABORATION WITH MICHELANGELO: DISTANCE AND PROXIMITY TO THE DIVINE IN CATHOLIC REFORMATION ROME by Marsha Libina A dissertation submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland April, 2015 © 2015 Marsha Libina All Rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation is structured around seven paintings that mark decisive moments in Sebastiano del Piombo’s Roman career (1511-47) and his collaboration with Michelangelo. Scholarship on Sebastiano’s collaborative works with Michelangelo typically concentrates on the artists’ division of labor and explains the works as a reconciliation of Venetian colorito (coloring) and Tuscan disegno (design). Consequently, discourses of interregional rivalry, center and periphery, and the normativity of the Roman High Renaissance become the overriding terms in which Sebastiano’s work is discussed. What has been overlooked is Sebastiano’s own visual intelligence, his active rather than passive use of Michelangelo’s skills, and the novelty of his works, made in response to reform currents of the early sixteenth century. This study investigates the significance behind Sebastiano’s repeating, slowing down, and narrowing in on the figure of Christ in his Roman works. The dissertation begins by addressing Sebastiano’s use of Michelangelo’s drawings as catalysts for his own inventions, demonstrating his investment in collaboration and strategies of citation as tools for artistic image-making. Focusing on Sebastiano’s reinvention of his partner’s drawings, it then looks at the ways in which the artist engaged with the central debates of the Catholic Reformation – debates on the Church’s mediation of the divine, the role of the individual in the path to personal salvation, and the increasingly problematic distance between the layperson and God. -

WISHBOOK-2019.Pdf

FRONT COVER Crivelli Madonna with Child - Carlo Crivelli XV - XVI Century Art Department pages 136 - 139 Contents 3 4 Letter from the President of the Vatican City State 94 Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints 6 Letter from the Director of the Vatican Museums 98 Enthroned Madonna and Child Letter from the International Director of the 102 Saints Paola and Eustochium 8 Patrons of the Arts 106 Stories of the Passion of Christ 110 Icons from the Tower of Pope John XXIII 10 BRAMANTE COURTYARD Long-term Project Report 126 XV – XVI CENTURY ART 16 CHRISTIAN ANTIQUITIES 128 Tryptich of the Madonna and Child with Saints 18 Drawn Replicas of Christian Catacombs Paintings 132 Apse of the Church of San Pellegrino 22 GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITIES 136 Crivelli Madonna with Child 24 Chiaramonti Gallery Wall XlV 140 Madonna and Child with Annunciation and Saints 30 Ostia Collection: Eleven Figurative Artifacts 144 XVII – XVIII CENTURY ART AND TAPESTRIES Ostia Collection: Two Hundred and Eighty-three 34 Household Artifacts 146 Noli Me Tangere Tapestry 38 Statue of an Old Fisherman 150 Plaster Cast of the Bust of Pope Pius VII 42 Polychrome Mosaic with Geometric Pattern 154 Two Works from the Workshop of Canova 162 Portrait of Pope Clement IX 46 GREGORIAN ETRUSCAN ANTIQUITIES 166 Embroidery Drawings for Papal Vestments 48 Krater, Kylixes and Perfume Jars 52 Gold Necklaces from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb 170 XIX CENTURY AND CONTEMPORARY ART 56 Astarita Collection: Thirty-three Figurative Vases 172 Clair de Lune 60 Ceremonial Clasp from the Regolini-Galassi Tomb 176 Model of Piazza Pius XII 64 Amphora and a Hundred Fragments of Bucchero 180 HISTORICAL COLLECTIONS 68 DECORATIVE ARTS 182 Two Jousting Shields 70 Rare Liturgical Objects 186 Drawing of the Pontifical Army Tabella 76 Tunic of “St. -

Management Plan Men Agement Plan Ement

MANAGEMENTAGEMENTMANAGEMENTEMENTNAGEMENTMEN PLAN PLAN 2006 | 2008 Historic Centre of Florence UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE he Management Plan of the His- toric Centre of Florence, approved T th by the City Council on the 7 March 2006, is under the auspices of the Historic Centre Bureau - UNESCO World Heritage of the Department of Culture of the Florence Municipality In charge of the Management Plan and coordinator of the project: Carlo Francini Text by: Carlo Francini Laura Carsillo Caterina Rizzetto In the compilation of the Management Plan, documents and data provided di- rectly by the project managers have also been used. INDEXEX INDEX INTRODUCTIONS CHAPTER V 45 Introduction by Antonio Paolucci 4 Socio-economic survey Introduction by Simone Siliani 10 V.1 Population indicators 45 V.2 Indicators of temporary residence. 46 FOREWORD 13 V.3 Employment indicators 47 V.4 Sectors of production 47 INTRODUCTION TO THE MANAGEMENT 15 V.5 Tourism and related activities 49 PLANS V.6 Tourism indicators 50 V.7 Access and availability 51 FIRST PART 17 V.8 Traffi c indicators 54 GENERAL REFERENCE FRAME OF THE PLAN V.9 Exposure to various sources of pollution 55 CHAPTER I 17 CHAPTER VI 56 Florence on the World Heritage List Analysis of the plans for the safeguarding of the site I.1 Reasons for inclusion 17 VI.1 Urban planning and safeguarding methods 56 I.2 Recognition of Value 18 VI. 2 Sector plans and/or integrated plans 60 VI.3 Plans for socio-economic development 61 CHAPTER II 19 History and historical identity CHAPTER VII 63 II.1 Historical outline 19 Summary -

MASTER DRAWINGS Index to Volumes 1–55 1963–2017 Compiled by Maria Oldal [email protected]

MASTER DRAWINGS Index to Volumes 1–55 1963–2017 Compiled by Maria Oldal [email protected] The subject of articles or notes is printed in CAPITAL letters; book and exhibition catalogue titles are given in italics; volume numbers are in Roman numerals and in bold face. Included in individual artist entries are authentic works, studio works, copies, attributions, etc., arranged in sequential order within the citations for each volume. When an author has written reviews, that designation appears at the end of the review citations. Names of collectors are in italics. Abbreviated names of Italian churches are alphabetized as if fully spelled out: "Rome, S. <San> Pietro in Montorio" precedes "S. <Santa> Maria del Popolo." Concordance of Master Drawings volumes and year of publication: I 1963 XII 1974 XXIII–XXIV 1985–86 XXXV 1997 XLVI 2008 II 1964 XIII 1975 XXV 1987 XXXVI 1998 XLVII 2009 III 1965 XIV 1976 XXVI 1988 XXXVII 1999 XLVIII 2010 IV 1966 XV 1977 XXVII 1989 XXXVIII 2000 XLIX 2011 V 1967 XVI 1978 XXVIII 1990 XXXIX 2001 L 2012 VI 1968 XVII 1979 XXIX 1991 XL 2002 LI 2013 VII 1969 XVIII 1980 XXX 1992 XLI 2003 LII 2014 VIII 1970 XIX 1981 XXXI 1993 XLII 2004 LIII 2015 IX 1971 XX 1982 XXXII 1994 XLIII 2005 LIV 2016 X 1972 XXI 1983 XXXIII 1995 XLIV 2006 LV 2017 XI 1973 XXII 1984 XXXIV 1996 XLV 2007 À l’ombre des frondaisons d’Arcueil: Dessiner un jardin du XVIIe siècle, exh. cat. by Xavier Salmon et al. Review. LIV: 397–404 A. S. -

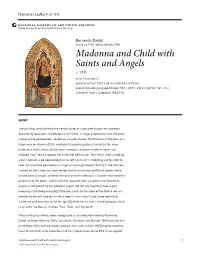

Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Bernardo Daddi active by 1320, died probably 1348 Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels c. 1345 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.2 x 24.2 cm (19 3/4 x 9 1/2 in.) overall (including engaged frame): 57.1 × 30.5 × 2.6 cm (22 1/2 × 12 × 1 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1952.5.61 ENTRY The painting, which formed the central panel of a portable triptych for domestic devotion,[1] represents the Madonna and Child, in larger proportions than the other figures in the composition, seated on a raised throne. The throne is in the form of a tabernacle or ciborium;[2] its crocketed triangular gable is framed by the inner trefoil arch of the panel, and its inner canopy is decorated with an azure star- studded “sky.” Mary supports her child with both hands. The Christ child is holding a fruit, perhaps a pomegranate,[3] in his left hand and is stretching out his right to take the small bird perched on a finger of the angel closest to him.[4] The throne is flanked on both sides by a red seraph and an azure cherub [5] and, below these, by two pairs of angels, of which the one to the far left plays a shawm—the medieval precursor of the oboe—and that on the opposite side a psaltery; the concert of angels is completed by the portative organ and the viol played by two angels kneeling in the foreground.[6] Of the four saints to the sides of the throne we can identify, to the left, Apollonia, with a tooth in her hand,[7] and, more doubtfully,