Africa to the Alps the Army Air Forces in the Mediterranean Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major-General Jennie Carignan Enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986

MAJOR-GENERAL M.A.J. CARIGNAN, OMM, MSM, CD COMMANDING OFFICER OF NATO MISSION IRAQ Major-General Jennie Carignan enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986. In 1990, she graduated in Fuel and Materials Engineering from the Royal Military College of Canada and became a member of Canadian Military Engineers. Major-General Carignan commanded the 5th Combat Engineer Regiment, the Royal Military College in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, and the 2nd Canadian Division/Joint Task Force East. During her career, Major-General Carignan held various staff Positions, including that of Chief Engineer of the Multinational Division (Southwest) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that of the instructor at the Canadian Land Forces Command and Staff College. Most recently, she served as Chief of Staff of the 4th Canadian Division and Chief of Staff of Army OPerations at the Canadian Special OPerations Forces Command Headquarters. She has ParticiPated in missions abroad in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Golan Heights, and Afghanistan. Major-General Carignan received her master’s degree in Military Arts and Sciences from the United States Army Command and General Staff College and the School of Advanced Military Studies. In 2016, she comPleted the National Security Program and was awarded the Generalissimo José-María Morelos Award as the first in her class. In addition, she was selected by her peers for her exemPlary qualities as an officer and was awarded the Kanwal Sethi Inukshuk Award. Major-General Carignan has a master’s degree in Business Administration from Université Laval. She is a reciPient of the Order of Military Merit and the Meritorious Service Medal from the Governor General of Canada. -

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

The War Years

1941 - 1945 George Northsea: The War Years by Steven Northsea April 28, 2015 George Northsea - The War Years 1941-42 George is listed in the 1941 East High Yearbook as Class of 1941 and his picture and the "senior" comments about him are below: We do know that he was living with his parents at 1223 15th Ave in Rockford, Illinois in 1941. The Rockford, Illinois city directory for 1941 lists him there and his occupation as a laborer. The Rockford City Directory of 1942 lists George at the same address and his occupation is now "Electrician." George says in a journal written in 1990, "I completed high school in January of 1942 (actually 1941), but graduation ceremony wasn't until June. In the meantime I went to Los Angeles, California. I tried a couple of times getting a job as I was only 17 years old. I finally went to work for Van De Camp restaurant and drive-in as a bus boy. 6 days a week, $20.00 a week and two meals a day. The waitresses pitched in each week from their tips for the bus boys. That was another 3 or 4 dollars a week. I was fortunate to find a garage apartment a few blocks from work - $3 a week. I spent about $1.00 on laundry and $2.00 on cigarettes. I saved money." (italics mine) "The first part of May, I quit my job to go back to Rockford (Illinois) for graduation. I hitch hiked 2000 miles in 4 days. I arrived at my family's house at 4:00 AM one morning. -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

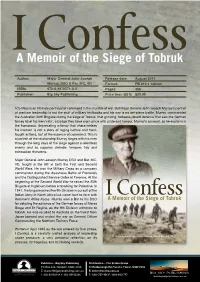

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

Heritage, Landscape and Conflict Archaeology

THE EDGE OF EUROPE: HERITAGE, LANDSCAPE AND CONFLICT ARCHAEOLOGY by ROXANA-TALIDA ROMAN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The research presented in this thesis addresses the significance of Romanian WWI sites as places of remembrance and heritage, by exploring the case of Maramureș against the standards of national and international heritage standards. The work provided the first ever survey of WWI sites on the Eastern Front, showing that the Prislop Pass conflictual landscape holds undeniable national and international heritage value both in terms of physical preservation and in terms of mapping on the memorial-historical record. The war sites demonstrate heritage and remembrance value by meeting heritage criteria on account of their preservation state, rarity, authenticity, research potential, the embedded war knowledge and their historical-memorial functions. The results of the research established that the war sites not only satisfy heritage legal requirements at various scales but are also endangered. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Eib Information

EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BAN ¡998 1958 Φ+ilô EIB INFORMATION DEN EUROPÆISKE INVESTERINGSBANK BANQUE EUROPEENNE D'INVESTISSEMENT EUROPÄISCHE INVESTITIONSBANK BANCA EUROPEA PER GII INVESTIMENTI EUROPESE INVESTERINGSBANK ΕΥΡΩΠΑΪΚΗ ΤΡΑΠΕΖΑ ΕΠΕΝΔΥΣΕΩΝ BANCO EUROPEU DE INVESTIMENTO 1 1998·Ν°96 EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK EUROOPAN INVESTOINTIPANKKI ISSN 02503891 BANCO EUROPEO DE INVERSIONES EUROPEISKA INVESTERINGSBANKEN 1997: European Investment Bank aunches ¡ob-support action plan and strengthens its commitment to EMU In 1997, the European Investment Bank intensified its support for economic and social cohesion in Europe in the run up to Economic and Monetary Union. The Bank launched a special action programme to encourage job-creating investment to underpin the European Union's growth and employment policies, and expanded its financing for investment in key areas sucri as regional development and Trans-European Networks. Total lending in the year increased by 13%, to ECU 26.2 billion (of which ECU 23 billion was in the Member States of the Union) and the Bank borrowed ECU 23 billion on the international capital markets, making it the world's largest non-sovereign borrower. "Our two top priorities during 1997 have been to step up our activities to help the European Union move successfully towards Economic and Monetary Union and the single currency and to prepare the way for the Union's enlargement. We responded rapidly and in a practical way to the Resolution on Growth and Employment of the June Amsterdam Summit by launching our Amsterdam Special Action Programme (ASAP). This is now well under way with substantial financing operations already con cluded in the areas of health and education and through a "special window" for venture capital, in the high-growth, technology oriented, small and medium-sized enterprise sector. -

1945-12-11 GO-116 728 ROB Central Europe Campaign Award

GO 116 SWAR DEPARTMENT No. 116. WASHINGTON 25, D. C.,11 December- 1945 UNITS ENTITLED TO BATTLE CREDITS' CENTRAL EUROPE.-I. Announcement is made of: units awarded battle par- ticipation credit under the provisions of paragraph 21b(2), AR 260-10, 25 October 1944, in the.Central Europe campaign. a. Combat zone.-The.areas occupied by troops assigned to the European Theater of" Operations, United States Army, which lie. beyond a line 10 miles west of the Rhine River between Switzerland and the Waal River until 28 March '1945 (inclusive), and thereafter beyond ..the east bank of the Rhine.. b. Time imitation.--22TMarch:,to11-May 1945. 2. When'entering individual credit on officers' !qualiflcation cards. (WD AGO Forms 66-1 and 66-2),or In-the service record of enlisted personnel. :(WD AGO 9 :Form 24),.: this g!neial Orders may be ited as: authority forsuch. entries for personnel who were present for duty ".asa member of orattached' to a unit listed&at, some time-during the'limiting dates of the Central Europe campaign. CENTRAL EUROPE ....irst Airborne Army, Headquarters aMd 1st Photographic Technical Unit. Headquarters Company. 1st Prisoner of War Interrogation Team. First Airborne Army, Military Po1ie,e 1st Quartermaster Battalion, Headquar- Platoon. ters and Headquarters Detachment. 1st Air Division, 'Headquarters an 1 1st Replacementand Training Squad- Headquarters Squadron. ron. 1st Air Service Squadron. 1st Signal Battalion. 1st Armored Group, Headquarters and1 1st Signal Center Team. Headquarters 3attery. 1st Signal Radar Maintenance Unit. 19t Auxiliary Surgical Group, Genera]1 1st Special Service Company. Surgical Team 10. 1st Tank DestroyerBrigade, Headquar- 1st Combat Bombardment Wing, Head- ters and Headquarters Battery.: quarters and Headquarters Squadron. -

WHO's WHO in the WAR in EUROPE the War in Europe 7 CHARLES DE GAULLE

who’s Who in the War in Europe (National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3A-20068.) POLITICAL LEADERS Allies FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT When World War II began, many Americans strongly opposed involvement in foreign conflicts. President Roosevelt maintained official USneutrality but supported measures like the Lend-Lease Act, which provided invaluable aid to countries battling Axis aggression. After Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States, Roosevelt rallied the country to fight the Axis powers as part of the Grand Alliance with Great Britain and the Soviet Union. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-128765.) WINSTON CHURCHILL In the 1930s, Churchill fiercely opposed Westernappeasement of Nazi Germany. He became prime minister in May 1940 following a German blitzkrieg (lightning war) against Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. He then played a pivotal role in building a global alliance to stop the German juggernaut. One of the greatest orators of the century, Churchill raised the spirits of his countrymen through the war’s darkest days as Germany threatened to invade Great Britain and unleashed a devastating nighttime bombing program on London and other major cities. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USW33-019093-C.) JOSEPH STALIN Stalin rose through the ranks of the Communist Party to emerge as the absolute ruler of the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, he conducted a reign of terror against his political opponents, including much of the country’s top military leadership. His purge of Red Army generals suspected of being disloyal to him left his country desperately unprepared when Germany invaded in June 1941. -

Air-To-Ground Battle for Italy

Air-to-Ground Battle for Italy MICHAEL C. MCCARTHY Brigadier General, USAF, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2004 Air University Library Cataloging Data McCarthy, Michael C. Air-to-ground battle for Italy / Michael C. McCarthy. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-128-7 1. World War, 1939–1945 — Aerial operations, American. 2. World War, 1939– 1945 — Campaigns — Italy. 3. United States — Army Air Forces — Fighter Group, 57th. I. Title. 940.544973—dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112–6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix INTRODUCTION . xi Notes . xiv 1 GREAT ADVENTURE BEGINS . 1 2 THREE MUSKETEERS TIMES TWO . 11 3 AIR-TO-GROUND BATTLE FOR ITALY . 45 4 OPERATION STRANGLE . 65 INDEX . 97 Photographs follow page 28 iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Foreword The events in this story are based on the memory of the author, backed up by official personnel records. All survivors are now well into their eighties. Those involved in reconstructing the period, the emotional rollercoaster that was part of every day and each combat mission, ask for understanding and tolerance for fallible memories. Bruce Abercrombie, our dedicated photo guy, took most of the pictures. -

Soldiers and Statesmen

, SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number008-070-00335-0 Catalog Number D 301.78:970 The Military History Symposium is sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy 1970 Military History Symposium Steering Committee: Colonel Alfred F. Hurley, Chairman Lt. Colonel Elliott L. Johnson Major David MacIsaac, Executive Director Captain Donald W. Nelson, Deputy Director Captain Frederick L. Metcalf SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN The Proceedings of the 4th Military History Symposium United States Air Force Academy 22-23 October 1970 Edited by Monte D. Wright, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy and Lawrence J. Paszek, Office of Air Force History Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy Washington: 1973 The Military History Symposia of the USAF Academy 1. May 1967. Current Concepts in Military History. Proceedings not published. 2. May 1968. Command and Commanders in Modem Warfare. Proceedings published: Colorado Springs: USAF Academy, 1269; 2d ed., enlarged, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972. 3. May 1969. Science, Technology, and Warfare. Proceedings published: Washington, b.C.: Government Printing Office, 197 1. 4. October 1970. Soldiers and Statesmen. Present volume. 5. October 1972. The Military and Society. Proceedings to be published. Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy.