Afghanistan: the Prospects for a Real Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Pakistanonedge.Pdf

Pakistan Project Report April 2013 Pakistan on the Edge Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 2013 Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in ISBN: 978-93-82512-02-8 First Published: April 2013 Cover shows Data Ganj Baksh, popularly known as Data Durbar, a Sufi shrine in Lahore. It is the tomb of Syed Abul Hassan Bin Usman Bin Ali Al-Hajweri. The shrine was attacked by radical elements in July 2010. The photograph was taken in August 2010. Courtesy: Smruti S Pattanaik. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. Published by: Magnum Books Pvt Ltd Registered Office: C-27-B, Gangotri Enclave Alaknanda, New Delhi-110 019 Tel.: +91-11-42143062, +91-9811097054 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.magnumbooks.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). Contents Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 Political Scenario: The Emerging Trends Amit Julka, Ashok K. Behuria and Sushant Sareen 13 Chapter 2 Provinces: A Strained Federation Sushant Sareen and Ashok K. Behuria 29 Chapter 3 Militant Groups in Pakistan: New Coalition, Old Politics Amit Julka and Shamshad Ahmad Khan 41 Chapter 4 Continuing Religious Radicalism and Ever Widening Sectarian Divide P. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs December 21, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30588 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Summary Stated U.S. policy is to ensure that Afghanistan will not again become a base for terrorist attacks against the United States. Following policy reviews in 2009, the Obama Administration asserted that it was pursuing a well-resourced and integrated military-civilian strategy intended to pave the way for a gradual transition to Afghan leadership from July 2011 until the end of 2014. To carry out U.S. policy, a total of 51,000 additional U.S. forces were authorized by the two 2009 reviews, which brought U.S. troop numbers to a high of about 99,000, with partner forces adding about 42,000. On June 22, 2011, President Obama announced that the policy had accomplished most major U.S. goals and that a drawdown of 33,000 U.S. troops would take place by September 2012. The first 10,000 of these are to be withdrawn by the end of 2011 and the remainder of that number by September 2012. The transition to Afghan leadership began, as planned, in July 2011 in the first set of areas, four cities and three full provinces; a second and larger tranche of areas to be transitioned was announced on November 27, 2011. The U.S. official view is that security gains achieved by the surge could be at risk from weak Afghan governance and insurgent safe haven in Pakistan, and that Afghanistan will still need direct security assistance after 2014. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 494 | MAY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org The Evolution and Potential Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan By Amira Jadoon Contents Introduction ...................................3 The Rise and Decline of the TTP, 2007–18 .....................4 Signs of a Resurgent TPP, 2019–Early 2021 ............... 12 Regional Alliances and Rivalries ................................ 15 Conclusion: Keeping the TTP at Bay ............................. 19 A Pakistani soldier surveys what used to be the headquarters of Baitullah Mehsud, the TTP leader who was killed in March 2010. (Photo by Pir Zubair Shah/New York Times) Summary • Established in 2007, the Tehrik-i- attempts to intimidate local pop- regional affiliates of al-Qaeda and Taliban Pakistan (TTP) became ulations, and mergers with prior the Islamic State. one of Pakistan’s deadliest militant splinter groups suggest that the • Thwarting the chances of the TTP’s organizations, notorious for its bru- TTP is attempting to revive itself. revival requires a multidimensional tal attacks against civilians and the • Multiple factors may facilitate this approach that goes beyond kinetic Pakistani state. By 2015, a US drone ambition. These include the Afghan operations and renders the group’s campaign and Pakistani military Taliban’s potential political ascend- message irrelevant. Efforts need to operations had destroyed much of ency in a post–peace agreement prioritize investment in countering the TTP’s organizational coherence Afghanistan, which may enable violent extremism programs, en- and capacity. the TTP to redeploy its resources hancing the rule of law and access • While the TTP’s lethality remains within Pakistan, and the potential to essential public goods, and cre- low, a recent uptick in the number for TTP to deepen its links with ating mechanisms to address legiti- of its attacks, propaganda releases, other militant groups such as the mate grievances peacefully. -

December 2020 MLM

VOLUME XI, ISSUE 12, DECEMBER 2020 THE JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION Michigan’s Sayf Abdulrab Debretsion Wolverine Salem al- Gebremichael: Post-Mortem Watchmen: A Hayashi: AQAP’s The Leader Mosaic of Analysis: Izzat al- Financial Conduit Behind the Boogaloo, Right- Douri and the to the Yemen- Rebellion in BRIEF Wing, and State of Iraq’s Somalia Weapons Tigray Anarchist Ba’ath Party Trade Militiamen ABDUL SAYED PETER KIRECHU MICHAEL HORTON JACOB ZENN RAMI JAMEEL VOLUME XI, ISSUE 12 | DECEMBER 2020 Waziristan Militant Leader Aleem remote areas bordering the country. The Khan Ustad Joins Tehreek-e-Taliban footages include video clips of both commanders' oath-taking, holding Mahsud's Abdul Sayed hands and announcing their pledges of allegiance to him. On December 15, Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, the emir of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Who is Mulawi Aleem Khan Ustad? appeared in a video released by Umar Media, the official media arm of TTP (Umar Media, Aleem Khan is from the tribal North Waziristan December 15). This video demonstrated a district, in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa continuation of the series of mergers of province, which served as the base of al-Qaeda Pakistani jihadist groups into TTP, which started for more than a decade after 9/11, from 2004 to in July 2020. 2015 (Asia Times, November 5). Khan was deputy to Hafiz Gul Bahadur—the al-Qaeda The video contains footage of the bay’ah (oath of host and shadow governor of Waziristan allegiance) ceremonies of two jihadist (Gandhara, March 16, 2015). The Gul Bahadur organizations from Waziristan, Pakistan, group became the largest local group in including Mulawi Aleem Khan Ustad, and Waziristan between 2008 and 2014 and even Commander Umar Azzam groups. -

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs August 17, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30588 Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy Summary At the end of 2014, the United States and partner countries completed a transition to a smaller mission consisting primarily of training and advising the Afghanistan National Security Forces (ANSF). The number of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, which peaked at about 100,000 in June 2011, stands at about 9,800. About 1,000 of the U.S. contingent are counter-terrorism forces that continue to conduct combat, operating under U.S. “Operation Freedom’s Sentinel” that has replaced the post-September 11 “Operation Enduring Freedom.” U.S. forces constitute the bulk of the 13,000-person NATO-led “Resolute Support Mission.” The post-2016 U.S. force is to be several hundred military personnel, under U.S. Embassy authority. However, amid assessments that the ANSF is having some difficulty preventing gains by the Taliban and other militant groups, President Obama announced that U.S. forces would remain at about 10,000 through the end of 2015. There has not been an announced change in the size in the post-2016 U.S. forces. U.S. officials assert that insurgents do not pose a threat to the stability of the government, but militants continue to conduct high-profile attacks and gain ground in some areas. The insurgency benefits, in some measure, from weak governance in Afghanistan. A dispute over the 2014 presidential election in Afghanistan was settled in September 2014 by a U.S.-brokered solution under which Ashraf Ghani became President and Dr. -

Tehrik E Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Militancy in Pakistan

Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies Vol. 7, No 3, September 2021 Volume and Issues Obtainable at Center for Sustainability Research and Consultancy Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies ISSN: 2519-089X & ISSN (E): 2519-0326 Volume 7: Issue 3 September 2021 Journal homepage: www.publishing.globalcsrc.org/jbsee Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Militancy in Pakistan *Surriya Shahab, PhD Scholar, Institute of Social and Cultural Studies, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan Muhammad Idrees, Visiting Lecturer, Pakistan Studies, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan Shaida Rasool, Visiting Lecturer, Pakistan Studies, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan Samana Mehreen, Visiting Lecturer, Pakistan Studies, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT History Purpose: Negotiations between two parties always have Revised format: Aug 2021 newsworthiness. Results of the negotiations can be strongly Available Online: Sep 2021 influenced by the media coverage. Pakistan’s government was also involved in peace negotiation with Tahrik e Taliban Pakistan Keywords (TTP) during January and February 2014. It was the most Peace talks, discussing issue in Pakistani media at that time. The aim of this Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Agenda Setting, research is to analyze the editorial policy of three Pakistani Editorial Policy, English language newspapers; Dawn, Nation and The News to Comparative Analysis check their favorable or unfavorable behavior regarding peace JEL Classification talks during January and February 2014. Z00, Z29 Design/Methodology/Approach: Agenda setting, priming and farming theories were used in this study. Qualitative content analysis method was used in this study to analyze the editorial policy of these three newspapers. -

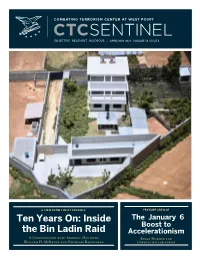

Ctc Sentinel 042021

OBJECTIVE ·· RELEVANT ·· RIGOROUS || JUNE/JULYAPRIL/MAY 2018 2021 · ·VOLUME VOLUME 11, 14, ISSUE ISSUE 6 4 A VIEWFEATURE FROM THE ARTICLE CT FOXHOLE A VIEWFEATURE FROM THE ARTICLE CT FOXHOLE TenThe Years Jihadi On: Threat Inside T h e J a n u a r y 6 LTC(R)Boost Bryan to Price theto Bin Indonesia Ladin Raid Accelerationism A Conversation with Admiral (Retired) Brian Former Hughes Director, and William H. McRavenKirsten and E. Schulze Nicholas Rasmussen CombatingCynthia Terrorism miller-idriss Center INTERVIEW Editor in Chief 1 A View from the CT Foxhole: Admiral (Retired) William H. McRaven, Former Commander, U.S. Special Operations Command, and Nicholas Paul Cruickshank Rasmussen, Former National Counterterrorism Center Director, Reflect on the Usama bin Ladin Raid Managing Editor Audrey Alexander Kristina Hummel FEATURE ARTICLE EDITORIAL BOARD 12 Uniting for Total Collapse: The January 6 Boost to Accelerationism Colonel Suzanne Nielsen, Ph.D. Brian Hughes and Cynthia Miller-Idriss Department Head Dept. of Social Sciences (West Point) ANALYSIS Lieutenant Colonel Sean Morrow 19 The March 2021 Palma Attack and the Evolving Jihadi Terror Threat to Director, CTC Mozambique Tim Lister Brian Dodwell 28 The Revival of the Pakistani Taliban Executive Director, CTC Abdul Sayed and Tore Hamming Don Rassler 39 A New Approach Is Necessary: The Policy Ramifications of the April 2021 Loyalist Violence in Northern Ireland Director of Strategic Initiatives, CTC Aaron Edwards CONTACT Ten years ago, the United States launched Operation Neptune Spear, the Combating Terrorism Center May 2011 raid on Usama bin Ladin’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, U.S. Military Academy which resulted in the death of al-Qa`ida’s founder. -

Bibliography: Terrorism by Country – Pakistan

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 4 Bibliography: Terrorism by Country – Pakistan Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes [Bibliographic Series of Perspectives on Terrorism – BSPT-JT-2019-7] Abstract This bibliography contains journal articles, book chapters, books, edited volumes, theses, grey literature, bibliographies and other resources on terrorism affecting Pakistan. It covers both terrorist activity within the country’s borders (regardless of the perpetrators’ nationality) and terrorist activity by Pakistani nationals abroad. While focusing on recent literature, the bibliography is not restricted to a particular time period and covers publications up to July 2019. The literature has been retrieved by manually browsing more than 200 core and periphery sources in the field of Terrorism Studies. Additionally, full-text and reference retrieval systems have been employed to broaden the search. Keywords: bibliography, resources, literature, terrorism, Pakistan, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, TTP, Al-Qaeda, Lashkar-e-Taiba, Islamic State, FATA, Kashmir NB: All websites were last visited on 20.07.2019. - See also Note for the Reader at the end of this literature list. Bibliographies and other Resources Atkins, Stephen E. (2011): Annotated Bibliography. In: Stephen E. Atkins (Ed.): The 9/11 Encyclopedia. (Vol. 1). (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 481-508. Bergen, Peter et al. (n.d.-): Drone Strikes: Pakistan. In: America’s Counterterrorism Wars. (New America In- Depth Report). URL: https://www.newamerica.org/in-depth/americas-counterterrorism-wars/pakistan Bueno de Mesquita, Ethan et al. (Principal Investigators) (2013): The BFRS Political Violence in Pakistan Dataset. URL: https://esoc.princeton.edu/files/bfrs-political-violence-pakistan-dataset Counter Extremism Project (CEP) (n.d.-): Pakistan: Extremism & Counter-Extremism. -

Human Aspects in Afghanistan Handbook

NATO HUMINT CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE HUMAN ASPECTS IN AFGHANISTAN HANDBOOK ORADEA - 2013 - NATO HUMINT CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE HUMAN ASPECTS IN AFGHANISTAN HANDBOOK ORADEA 2013 Realized within Human Aspects of the Operational Environment Project, NATO HUMINT Centre of Excellence Coordinator: Col. Dr. Eduard Simion Technical coordination and cover: Col. Răzvan Surdu, Maj. Peter Kovacs Technical Team: Maj. Constantin Sîrmă, OR-9 Dorian Bănică NATO HUMINT Centre of Excellence Human Aspects in Afghanistan Handbook / NATO HUMINT Centre of Excellence – Oradea, HCOE, 2013 Project developed under the framework of NATO's Defence against Terrorism Programme of Work with the support of Emerging Security Challenges Division/ NATO HQ. © 2013 by NATO HUMINT Centre of Excellence All rights reserved Printed by: CNI Coresi SA “Imprimeria de Vest” Subsidiary 35 Calea Aradului, Oradea Human Aspects in Afghanistan - Handbook EDITORIAL TEAM Zobair David DEEN, International Security Assistance Force Headquarters, SME Charissa DEEN, University of Manitoba, Instructor Aemal KARUKHALE, International Security Assistance Force Headquarters, SME Peter KOVÁCS, HUMINT Centre of Excellence, Major, Slovak Armed Forces Hubertus KÖBKE, United Nations, Lieutenant-Colonel German Army Reserve Luděk MICHÁLEK, Police Academy of the Czech Republic, Lieutenant Colonel, Czech Army (Ret.) Ralf Joachim MUMM, The Defence Committee of the Federal German Parliament Ali Zafer ÖZSOY, HUMINT Centre of Excellence, Colonel, Turkish Army Lesley SIMM, Allied Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC), NATO, SME -

Pakistani Taliban January 2013

Issues Paper The Pakistani Taliban January 2013 Contents 1. TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................................ 2 2. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW .............................................................................................. 2 3. GROUPS ............................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) ..................................................................................... 4 3.1.1 Organisation .................................................................................................................. 4 3.1.2 Tribes and Tribal Infighting .......................................................................................... 6 3.1.3 Recruitment ................................................................................................................... 7 3.1.4 Area of Influence .......................................................................................................... 8 3.1.5 Aims .............................................................................................................................. 9 3.1.6 Connections................................................................................................................. 13 3.2 Muqami Tehrik-e-Taliban (MTT).................................................................................. 14 3.2.1 The Mullah Nazir Group ............................................................................................ -

Pakistan Security Report 2018

Conflict and Peace Studies VOLUME 11 Jan - June 2019 NUMBER 1 PAKISTAN SECURITY REPORT 2018 PAK INSTITUTE FOR PEACE STUDIES (PIPS) A PIPS Research Journal Conflict and Peace Studies Copyright © PIPS 2019 All Rights Reserved No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form by photocopying or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without prior permission in writing from the publisher of this journal. Editorial Advisory Board Khaled Ahmed Dr. Catarina Kinnvall Consulting Editor, Department of Political Science, The Friday Times, Lahore, Pakistan. Lund University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Saeed Shafqat Dr. Adam Dolnik Director, Centre for Public Policy and Governance, Professor of Counterterrorism, George C. Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, Germany. Marco Mezzera Tahir Abbas Senior Adviser, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Professor of Sociology, Fatih University, Centre / Norsk Ressurssenter for Fredsbygging, Istanbul, Turkey. Norway. Prof. Dr. Syed Farooq Hasnat Rasul Bakhsh Rais Pakistan Study Centre, University of the Punjab, Professor, Political Science, Lahore, Pakistan. Lahore University of Management Sciences Lahore, Pakistan. Anatol Lieven Dr. Tariq Rahman Professor, Department of War Studies, Dean, School of Education, Beaconhouse King's College, London, United Kingdom. National University, Lahore, Pakistan. Peter Bergen Senior Fellow, New American Foundation, Washington D.C., USA. Pak Institute for Peace ISSN 2072-0408 ISBN 978-969-9370-32-8 Studies Price: Rs 1000.00 (PIPS) US$ 25.00 Post Box No. 2110, The views expressed are the authors' Islamabad, Pakistan own and do not necessarily reflect any +92-51-8359475-6 positions held by the institute.