Diseases of Pacific Coast Conifers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINAL REPORT Pines Vs

FINAL REPORT Pines vs. Oaks Revisited: Forest Type Conversion Due to High-severity Fire in Madrean Woodlands JFSP PROJECT ID: 15-1-07-22 December 2017 Andrew M. Barton University of Maine at Farmington Helen M. Poulos Wesleyan University Graeme P. Berlyn Yale University The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. ii Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................1 Objectives ........................................................................................................................................2 Background ......................................................................................................................................3 Materials and Methods .....................................................................................................................4 Study System .............................................................................................................................4 Climate and Fire Patterns in Southeastern Arizona ...................................................................6 Plot Sampling Design ................................................................................................................6 Plot -

Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA AGRARIA ANTONIO NARRO DIVISIÓN DE AGRONOMÍA Pinus arizonica Engelm. PRESENTA: SERGIO AMILCAR CANUL TUN MONOGRAFÍA Presentada como requisito parcial para Obtener el título de: INGENIERO FORESTAL Buenavista, Saltillo, Coahuila, México Mayo de 2005 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA AGRARIA ANTONIO NARRO DIVISIÓN DE AGRONOMÍA DEPARTAMENTO FORESTAL Pinus arizonica Engelm. MONOGRAFÍA Que somete a consideración del H. Jurado calificador como requisito parcial para obtener el título de: INGENIERO FORESTAL PRESENTA SERGIO AMILCAR CANUL TUN APROBADA PRESIDENTE DEL JURADO COORDINADOR DE LA DIVISIÓN DE AGRONOMÍA _____________________________ ________________________________ M. C. CELESTINO FLORES LÓPEZ M. C. ARNOLDO OYERVIDES GARCÍA Buenavista, Saltillo, Coahuila, México Mayo de 2005 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA AGRARIA ANTONIO NARRO DIVISIÓN DE AGRONOMÍA DEPARTAMENTO FORESTAL Pinus arizonica Engelm. MONOGRAFÍA Que somete a consideración del H. Jurado calificador como requisito parcial para obtener el título de: INGENIERO FORESTAL PRESENTA SERGIO AMILCAR CANUL TUN PRESIDENTE DEL JURADO _____________________________ M. C. CELESTINO FLORES LÓPEZ PRIMER SINODAL SEGUNDO SINODAL _______________________________ ___________________________________ Dr. MIGUEL ÁNGEL CAPÓ ARTEAGA Dr. JOSÉ ÁNGEL VILLARREAL QUINTANILLA Buenavista, Saltillo, Coahuila, México Mayo de 2005 DEDICATORIA A mis grandes amores: Leydi Abigail Cob Chan Nayvi Abisai Canul Cob Por haber llegado a mi vida y formar parte de mi, son un gran motivo para triunfar y salir adelante en medio de una gran tempestad. A mis padres: Ramón Cruz Canul Vázquez Lucila Tún Cahuich. Por su gran sacrificio realizado, por la confianza que me brindaron y por ser mis mejores amigos. Siempre tuve sus consejos, ayuda en el momento más crítico y comprensión. A mis hermanos: Claudio Ezequiel, por aceptar ser mi amigo, por su compañía y apoyo durante mi carrera y en este trabajo. -

Degree of Hybridization in Seed Stands of Pinus Engelmannii Carr

RESEARCH ARTICLE Degree of Hybridization in Seed Stands of Pinus engelmannii Carr. In the Sierra Madre Occidental, Durango, Mexico Israel Jaime Ávila-Flores1, José Ciro Hernández-Díaz2, Maria Socorro González-Elizondo3, José Ángel Prieto-Ruíz4, Christian Wehenkel2* 1 Doctorado Institucional en Ciencias Agropecuarias y Forestales, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Apdo, Postal 741, Zona Centro, Durango, Durango, México, C.P., 34000, 2 Instituto de Silvicultura e Industria de la Madera, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Apdo, Postal 741, Zona Centro, Durango, Durango, México, C.P., 34000, 3 CIIDIR Unidad Durango, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Sigma 119 Fracc, 20 de Noviembre II, Durango, Durango, México, C.P., 34220, 4 Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Blv. Durango y Ave, Papaloapan s/n. Col. Valle del Sur, Durango, Durango, México, C.P., 34120 * [email protected] Abstract Hybridization is an important evolutionary force, because interspecific gene transfer can introduce more new genetic material than is directly generated by mutations. Pinus engel- OPEN ACCESS mannii Carr. is one of the nine most common pine species in the pine-oak forest ecoregion Citation: Ávila-Flores IJ, Hernández-Díaz JC, in the state of Durango, Mexico. This species is widely harvested for lumber and is also González-Elizondo MS, Prieto-Ruíz JÁ, Wehenkel C used in reforestation programmes. Interspecific hybrids between P.engelmannii and Pinus (2016) Degree of Hybridization in Seed Stands of arizonica Engelm. have been detected by morphological analysis. The presence of hybrids Pinus engelmannii Carr. In the Sierra Madre in P. engelmannii seed stands may affect seed quality and reforestation success. -

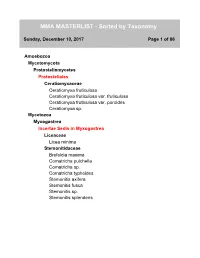

MMA MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

MMA MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, December 10, 2017 Page 1 of 86 Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Ceratiomyxa sp. Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Liceaceae Licea minima Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha pulchella Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Chromista Oomycota Incertae Sedis in Oomycota Peronosporales Peronosporaceae Plasmopara viticola Pythiaceae Pythium deBaryanum Oomycetes Saprolegniales Saprolegniaceae Saprolegnia sp. Peronosporea Albuginales Albuginaceae Albugo candida Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Scorias spongiosa Diaporthales Gnomoniaceae Cryptodiaporthe corni Sydowiellaceae Stegophora ulmea Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsella nigroannulata Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe aggregata Erysiphe cichoracearum Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera extensa Phyllactinia guttata Podosphaera clandestina Uncinula adunca Uncinula necator Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Leotiales Bulgariaceae Crinula caliciiformis Crinula sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Lobariaceae Sticta fimbriata Nephromataceae Nephroma helveticum Peltigeraceae Peltigera evansiana Peltigera -

PROCEEDINGS of the 25Th ANNUAL WESTERN INTERNATIONAL FOREST DISEASE WORK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS OF THE 25th ANNUAL WESTERN INTERNATIONAL FOREST DISEASE WORK CONFERENCE Victoria, British Columbia September 1977 Proceedings of the 25th Annual Western International Forest Disease Work Conference Victoria, British Columbia September 1977 Compiled by: This scan has not been edited or customized. The quality of the reproduction is based on the condition of the original source. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Western International Forest Disease Work Conference Victoria, British Columbia September 1977 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Forward Opening Remarks, Chairman Don Graham 2 Memorial Statement - Stuart R. Andrews 3 Welcoming Address: Forest Management in British Columbia with Particular Reference to the Province's Forest disease Problems Bill Young 5 Keynote Address: Forest Diseases as a Part of the Forest Ecosystem Paul Brett PANEL: REGULATORY FUNCTIONS OF DISEASES IN FOREST ECOSYSTEMS 10 Introduction to Regulatory Functions of Diseases in Forest Ecosystems J. R. Parmeter 11 Relationships of Tree Diseases and Stand Density Ed F. Wicker 13 Forest Diseases as Determinants of Stand Composition and Forest Succession Earl E. Nelson 18 Regulation of Site Selection James W. Byler 21 Disease and Generation Time J. R. Parmeter PANEL: INTENSIVE FOREST MANAGEMENT AS INFLUENCED BY FOREST DISEASES 22 Dwarf Mistletoe and Western Hemlock Management K. W. Russell 30 Phellinus weirii and Intensive Management Workshops as an aid in Reaching the Practicing Forester G. W. Wallis 33 Fornes annosus in Second-Growth Stands Duncan Morrison 36 Armillaria mellea and East Side Pine Management Gregory M. Filip 39 Thinning Second Growth Stands Paul E. Aho PANEL: KNOWLEDGE UTILIZATION IN WESTERN FOREST PATHOLOGY 44 Knowledge Utilization in Western Forest Pathology R Z. -

Chiricahua Firescape Draft Environmental Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture Chiricahua FireScape Draft Environmental Assessment Forest Service Coronado National Forest Douglas Ranger District September 2018 For More Information Contact: Renee Kuehner Fire Management Officer 1192 West Saddleview Road Douglas, AZ 85607 520-388-8448 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720- 2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632- 9992. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

THE TAXONOMY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DWARF MISTLETOES PARASITIZING WHITE PINES IN ARIZONA Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Mathiasen, Robert L. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 13:00:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289671 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

Mistletoes of North American Conifers

United States Department of Agriculture Mistletoes of North Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station American Conifers General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-98 September 2002 Canadian Forest Service Department of Natural Resources Canada Sanidad Forestal SEMARNAT Mexico Abstract _________________________________________________________ Geils, Brian W.; Cibrián Tovar, Jose; Moody, Benjamin, tech. coords. 2002. Mistletoes of North American Conifers. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–98. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 123 p. Mistletoes of the families Loranthaceae and Viscaceae are the most important vascular plant parasites of conifers in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Species of the genera Psittacanthus, Phoradendron, and Arceuthobium cause the greatest economic and ecological impacts. These shrubby, aerial parasites produce either showy or cryptic flowers; they are dispersed by birds or explosive fruits. Mistletoes are obligate parasites, dependent on their host for water, nutrients, and some or most of their carbohydrates. Pathogenic effects on the host include deformation of the infected stem, growth loss, increased susceptibility to other disease agents or insects, and reduced longevity. The presence of mistletoe plants, and the brooms and tree mortality caused by them, have significant ecological and economic effects in heavily infested forest stands and recreation areas. These effects may be either beneficial or detrimental depending on management objectives. Assessment concepts and procedures are available. Biological, chemical, and cultural control methods exist and are being developed to better manage mistletoe populations for resource protection and production. Keywords: leafy mistletoe, true mistletoe, dwarf mistletoe, forest pathology, life history, silviculture, forest management Technical Coordinators_______________________________ Brian W. Geils is a Research Plant Pathologist with the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Flagstaff, AZ. -

The Evolution of Cavitation Resistance in Conifers Maximilian Larter

The evolution of cavitation resistance in conifers Maximilian Larter To cite this version: Maximilian Larter. The evolution of cavitation resistance in conifers. Bioclimatology. Univer- sit´ede Bordeaux, 2016. English. <NNT : 2016BORD0103>. <tel-01375936> HAL Id: tel-01375936 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01375936 Submitted on 3 Oct 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE DE BORDEAUX Spécialité : Ecologie évolutive, fonctionnelle et des communautés Ecole doctorale: Sciences et Environnements Evolution de la résistance à la cavitation chez les conifères The evolution of cavitation resistance in conifers Maximilian LARTER Directeur : Sylvain DELZON (DR INRA) Co-Directeur : Jean-Christophe DOMEC (Professeur, BSA) Soutenue le 22/07/2016 Devant le jury composé de : Rapporteurs : Mme Amy ZANNE, Prof., George Washington University Mr Jordi MARTINEZ VILALTA, Prof., Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona Examinateurs : Mme Lisa WINGATE, CR INRA, UMR ISPA, Bordeaux Mr Jérôme CHAVE, DR CNRS, UMR EDB, Toulouse i ii Abstract Title: The evolution of cavitation resistance in conifers Abstract Forests worldwide are at increased risk of widespread mortality due to intense drought under current and future climate change. -

Some Factors Involved in the Success of Side Veneer Grafting of Pinus Engelmannii Carr

Article Some Factors Involved in the Success of Side Veneer Grafting of Pinus engelmannii Carr. Alberto Pérez-Luna 1, José Ángel Prieto-Ruíz 2, Javier López-Upton 3, Artemio Carrillo-Parra 4, Christian Wehenkel 4 , Jorge Armando Chávez-Simental 4 and José Ciro Hernández-Díaz 4,* 1 Programa Institucional de Doctorado en Ciencias Agropecuarias y Forestales, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Constitución 404 sur Zona Centro, Durango CP 34000, Mexico; [email protected] 2 Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Río Papaloapan y Blvd. Durango S/N Col. Valle del Sur, Durango CP 34120, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo, Carretera México-Texcoco Km 36.5, Montecillo CP 56230, Texcoco, Mexico; [email protected] 4 Instituto de Silvicultura e Industria de la Madera, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Boulevard del Guadiana 501, Ciudad Universitaria, Torre de Investigación, Durango CP 34120, Mexico; [email protected] (A.C.-P.); [email protected] (C.W.); [email protected] (J.A.C.-S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-618-825-1886 Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 29 January 2019; Published: 30 January 2019 Abstract: The establishment of clonal seed orchards is a viable option for the continuous production of improved seed of desired genotypes. Grafting is the main technique used to establish clonal seed orchards. The objective of this study was to examine how the geographic location and the age class of the donor trees of buds, the phenological status of the buds, and the anatomical characteristics of the scions and the rootstocks affect the survival and growth of Pinus engelmannii Carr. -

Redalyc.Can We Expect to Protect Threatened Species in Protected

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Aguirre Gutiérrez, Jesús; Duivenvoorden, Joost F. Can we expect to protect threatened species in protected areas? A case study of the genus Pinus in Mexico Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 81, núm. 3, 2010, pp. 875-882 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42518439027 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 81: 875 - 882, 2010 Can we expect to protect threatened species in protected areas? A case study of the genus Pinus in Mexico Podemos proteger especies en riesgo en áreas protegidas? Un estudio de caso del genero Pinus en México Jesús Aguirre Gutiérrez* and Joost F. Duivenvoorden Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystems Dynamics (IBED), Universiteit van Amsterdam, Science Park 904, 1098 HX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. *Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. The distribution of 56 Pinus species in Mexico was modelled with MAXENT. The pine species were classified as threatened according to IUCN criteria. Our aim was to ascertain whether or not threatened pine species were adequately represented in protected areas. Almost 70% of the species had less than 10% of their modelled distribution area protected. None of the pine species reached their representation targets. Threatened pine species were less widely distributed, occurred at lower maximum elevations, and were less well represented in protected areas than other pine species. -

Pinus Ponderosa : a Checkered Past Obscured Four Species1

RESEARCH ARTICLE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BOTANY Pinus ponderosa : A checkered past obscured four species 1 Ann Willyard2,10 , David S. Gernandt 3 , Kevin Potter 4 , Valerie Hipkins 5 , Paula Marquardt 6 , Mary Frances Mahalovich 7 , Stephen K. Langer 8 , Frank W. Telewski9 , Blake Cooper 2 , Connor Douglas 2 , Kristen Finch 2 , Hassani H. Karemera 2 , Julia Lefl er 2 , Payton Lea 2 , and Austin Woff ord 2 PREMISE OF THE STUDY: Molecular genetic evidence can help delineate taxa in species complexes that lack diagnostic morphological characters. Pinus ponderosa (Pinaceae; subsection Ponderosae ) is recognized as a problematic taxon: plastid phylogenies of exemplars were paraphyletic, and mitochon- drial phylogeography suggested at least four subdivisions of P. ponderosa . These patterns have not been examined in the context of other Ponderosae species. We hypothesized that putative intraspecifi c subdivisions might each represent a separate taxon. METHODS: We genotyped six highly variable plastid simple sequence repeats in 1903 individuals from 88 populations of P. ponderosa and related Pondero- sae ( P. arizonica , P. engelmannii , and P. jeff reyi ). We used multilocus haplotype networks and discriminant analysis of principal components to test cluster- ing of individuals into genetically and geographically meaningful taxonomic units. KEY RESULTS: There are at least four distinct plastid clusters within P. ponderosa that roughly correspond to the geographic distribution of mitochondrial haplotypes. Some geographic regions have intermixed plastid lineages, and some mitochondrial and plastid boundaries do not coincide. Based on rela- tive distances to other species of Ponderosae , these clusters diagnose four distinct taxa. CONCLUSIONS: Newly revealed geographic boundaries of four distinct taxa ( P.