(8-13Th C.): Contributing to a Reassessment List of Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadio-Byzantina a Newsletter Published by the Canadian Committee of No.32, January 2021 Byzantinists

Canadio-Byzantina A Newsletter published by the Canadian Committee of No.32, January 2021 Byzantinists St Saviour in Chora (Kariye Camii) the last judgement (14th century); the church, having been a museum, is now being reconverted to a mosque Contents: Book Review (S. Moffat) 26 Activities of Member 3 Obituaries 28 Reports & Articles AIEB business 30 Report on Baturyn (V. Mezentsev) 13 Short notices 33 The Perpetual Conquest (O. Heilo) 18 Disputatio Virtualis 34 Crisis at the Border CIBS 1990s lecture links 35 of Byzantium (p. boudreau) 22 Essay Competition 35 2 A Newsletter published by the Canadian Committee of Byzantinists No.32, January 2021 Introductory remarks Welcome to the ninth bulletin that I have put I have repeated some information from an earlier together, incorporating, as usual, reports on our issue here to do with the lectures given in the members’ activities, reports on conferences and 1990s, originally organised by the Canadian articles, a book review, and announcements on Institute for Balkan Studies; among the authors forthcoming activities or material or events of the papers are Speros Vyronis, Jr., Ihor relevant to Byzantinists. Ševèenko and Warren Treadgold. I alluded to them in passing last year, but I thought it sensible Readers will note that this issue is rather less to give full details here: see p.35 below. handsomely produced than than the last few, for which I can only apologise. Chris Dickert, who There is no need for me to comment here on the had polished the latest issues so well, is no problems all have faced this year; many longer available to help, so that I must fall back colleagues mention them in their annual reports. -

BYZANTINE CAMEOS and the AESTHETICS of the ICON By

BYZANTINE CAMEOS AND THE AESTHETICS OF THE ICON by James A. Magruder, III A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 2014 © 2014 James A. Magruder, III All rights reserved Abstract Byzantine icons have attracted artists and art historians to what they saw as the flat style of large painted panels. They tend to understand this flatness as a repudiation of the Classical priority to represent Nature and an affirmation of otherworldly spirituality. However, many extant sacred portraits from the Byzantine period were executed in relief in precious materials, such as gemstones, ivory or gold. Byzantine writers describe contemporary icons as lifelike, sometimes even coming to life with divine power. The question is what Byzantine Christians hoped to represent by crafting small icons in precious materials, specifically cameos. The dissertation catalogs and analyzes Byzantine cameos from the end of Iconoclasm (843) until the fall of Constantinople (1453). They have not received comprehensive treatment before, but since they represent saints in iconic poses, they provide a good corpus of icons comparable to icons in other media. Their durability and the difficulty of reworking them also makes them a particularly faithful record of Byzantine priorities regarding the icon as a genre. In addition, the dissertation surveys theological texts that comment on or illustrate stone to understand what role the materiality of Byzantine cameos played in choosing stone relief for icons. Finally, it examines Byzantine epigrams written about or for icons to define the terms that shaped icon production. -

The Role of Greek Culture Representation in Socio-Economic Development of the Southern Regions of Russia

European Research Studies Journal Volume XXI, Special Issue 1, 2018 pp. 136 - 147 The Role of Greek Culture Representation in Socio-Economic Development of the Southern Regions of Russia T.V. Evsyukova1, I.G. Barabanova2, O.V. Glukhova3, E.A. Cherednikova4 Abstract: This article researches how the Greek lingvoculture represented in onomasticon of the South of Russia. The South Russian anthroponyms, toponyms and pragmatonyms are considered in this article and how they verbalize the most important values and ideological views. It is proved in the article that the key concepts of the Greek lingvoculture such as: “Peace”, “Faith”, “Love”, “Heroism”, “Knowledge”, “Alphabet”, “Power”, “Charismatic person” and “Craft” are highly concentrated in the onomastic lexis of the researched region. The mentioned above concepts due to their specific pragmatic orientation are represented at different extend. Keywords: Culture, linguoculture, onomastics, concept anthroponym, toponym, pragmatonim. 1D.Sc. in Linguistics, Professor, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation. 2Ph.D. in Linguistics, Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation. 3Lecturer, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation, E-mail: [email protected] 4Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, Rostov State University of Economics, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation. T.V. Evsyukova, I.G. Barabanova, O.V. Glukhova, E.A. Cherednikova 137 1. Introduction There is unlikely to be any other culture that influenced so much on the formation of other European cultures, as the Greek culture. -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

A Study on the Scythian Torque

IJCC, Vol, 6, No. 2, 69〜82(2003) A Study on the Scythian Torque Moon-Ja Kim Professor, Dept, of Clothing & Textiles, Suwon University (Received May 2, 2003) Abstract The Scythians had a veritable passion for adornment, delighting in decorating themselves no less than their horses and belongings. Their love of jewellery was expressed at every turn. The most magnificent pieces naturally come from the royal tombs. In the area of the neck and chest the Scythian had a massive gold Torques, a symbol of power, made of gold, turquoise, cornelian coral and even amber. The entire surface of the torque, like that of many of the other artefacts, is decorated with depictions of animals. Scythian Torques are worn with the decorative terminals to the front. It was put a Torque on, grasped both terminals and placed the opening at the back of the neck. It is possible the Torque signified its wearer's religious leadership responsibilities. Scythian Torques were divided into several types according to the shape, Torque with Terminal style, Spiral style, Layers style, Crown style, Crescent-shaped pectoral style. Key words : Crescent-shaped pectoral style, Layers style, Scythian Torque, Spiral style, Terminal style role in the Scythian kingdom belonged to no I • Introduction mads and it conformed to nomadic life. A vivid description of the burial of the Scythian kings The Scythians originated in the central Asian and of ordinary members of the Scythian co steppes sometime in the early first millennium, mmunity is contained in Herodotus' History. The BC. After migrating into what is present-day basic characteristics of the Scythian funeral Ukraine, they flourished, from the seventh to the ritual (burials beneath Kurgans according to a third centuries, BC, over a vast expanse of the rite for lating body in its grave) remained un steppe that stretched from the Danube, east changed throughout the entire Scythian period.^ across what is modem Ukraine and east of the No less remarkable are the articles from the Black Sea into Russia. -

Colloquia Pontica Volume 10

COLLOQUIA PONTICA VOLUME 10 ATTIC FINE POTTERY OF THE ARCHAIC TO HELLENISTIC PERIODS IN PHANAGORIA PHANAGORIA STUDIES, VOLUME 1 COLLOQUIA PONTICA Series on the Archaeology and Ancient History of the Black Sea Area Monograph Supplement of Ancient West & East Series Editor GOCHA R. TSETSKHLADZE (Australia) Editorial Board A. Avram (Romania/France), Sir John Boardman (UK), O. Doonan (USA), J.F. Hargrave (UK), J. Hind (UK), M. Kazanski (France), A.V. Podossinov (Russia) Advisory Board B. d’Agostino (Italy), P. Alexandrescu (Romania), S. Atasoy (Turkey), J.G. de Boer (The Netherlands), J. Bouzek (Czech Rep.), S. Burstein (USA), J. Carter (USA), A. Domínguez (Spain), C. Doumas (Greece), A. Fol (Bulgaria), J. Fossey (Canada), I. Gagoshidze (Georgia), M. Kerschner (Austria/Germany), M. Lazarov (Bulgaria), †P. Lévêque (France), J.-P. Morel (France), A. Rathje (Denmark), A. Sagona (Australia), S. Saprykin (Russia), T. Scholl (Poland), M.A. Tiverios (Greece), A. Wasowicz (Poland) ATTIC FINE POTTERY OF THE ARCHAIC TO HELLENISTIC PERIODS IN PHANAGORIA PHANAGORIA STUDIES, VOLUME 1 BY CATHERINE MORGAN EDITED BY G.R. TSETSKHLADZE BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 All correspondence for the Colloquia Pontica series should be addressed to: Aquisitions Editor/Classical Studies or Gocha R. Tsetskhladze Brill Academic Publishers Centre for Classics and Archaeology Plantijnstraat 2 The University of Melbourne P.O. Box 9000 Victoria 3010 2300 PA Leiden Australia The Netherlands Tel: +61 3 83445565 Fax: +31 (0)71 5317532 Fax: +61 3 83444161 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Illustration on the cover: Athenian vessel, end of the 5th-beg. of the 4th cent. -

The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4

The Northern Black Sea Region by Kerstin Susanne Jobst In historical studies, the Black Sea region is viewed as a separate historical region which has been shaped in particular by vast migration and acculturation processes. Another prominent feature of the region's history is the great diversity of religions and cultures which existed there up to the 20th century. The region is understood as a complex interwoven entity. This article focuses on the northern Black Sea region, which in the present day is primarily inhabited by Slavic people. Most of this region currently belongs to Ukraine, which has been an independent state since 1991. It consists primarily of the former imperial Russian administrative province of Novorossiia (not including Bessarabia, which for a time was administered as part of Novorossiia) and the Crimean Peninsula, including the adjoining areas to the north. The article also discusses how the region, which has been inhabited by Scythians, Sarmatians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, Huns, Khazars, Italians, Tatars, East Slavs and others, fitted into broader geographical and political contexts. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Space of Myths and Legends 3. The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4. From the Khazar Empire to the Crimean Khanate and the Ottomans 5. Russian Rule: The Region as Novorossiia 6. World War, Revolutions and Soviet Rule 7. From the Second World War until the End of the Soviet Union 8. Summary and Future Perspective 9. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Literature 3. Notes Indices Citation Introduction -

Hazar Türkçesi Ve Hazar Türkçesi Leksikoloji Tespiti Denemesi

HAZAR TÜRKÇESİ VE HAZAR TÜRKÇESİ LEKSİKOLOJİ TESPİTİ DENEMESİ Pınar Özdemir* Özet Eski Türkçenin diyalektleri arasında sayılan Hazar Türkçesi ma- alesef ardında yazılı eserler bırakmamıştır. Çalışmamızda bilinenden bilinmeyene metoduyla hareket ede- rek ilk önce mevcut Hazar Türkçesine ait kelimeleri derleyip, ortak özelliklerini tespit edip, mihenk taşlarımızı oluşturduk. Daha sonra Hazar Devleti’nin yaşadığı coğrafyada bu gün yaşayan Türk hak- larının dillerinden Karaçay-Malkar, Karaim, Kırımçak ve Kumuk Türkçelerinin ortak kelimelerini tespit ettik. Bu ortak kelimelerin de leksik ve morfolojik özelliklerini belirledikten sonra birbirleriyle karşılaştırıp aralarındaki uyumu göz önüne sererek Hazar Türkçesi Leksikoloji Tespitini denedik. Anahtar Kelimeler : Hazar, Karaçay-Malkar, Karaim, Kırımçak, Kumuk AbstraCt Unfortunately there is not left any written works behind Khazar Turkish which is deemed to be one of the dialects of old Turkish. In our work primarily key voices, forms and the words of Khazar Turkish have been determined with respect to the features of voice and forms of the existing words remaining from that period. Apart from these determined key features it have been determined the mu- tual aspects of Karachay-Malkar, Karaim, Krymchak and Kumuk Turkish which are known as the remnants of Khazar and it has been intended to reveal the vocabulary of Khazar Turkish. Key Words : Khazar, Karachay-Malkar, Karaim, Kırımchak, Ku- muk Önceleri Göktürk Devletine bağlı olan Hazar Hakanlığı bu devletin iç ve dış savaşlar neticesinde yıkıldığı 630–650 yılları arasındaki süreçte devlet olma temellerini atmıştır. Kuruluşundan sonra hızla büyüyen bu devlet VII. ve X. yüzyıllar arasında Ortaçağın en önemli kuvvetlerinden biri halini almıştır. Hazar Devleti coğrafi sınırlarını batıda Kiev, kuzeyde Bulgar, güneyde Kırım * [email protected] Karadeniz Araştırmaları • Kış 2013 • Sayı 36 • 189-206 Pınar Özdemir ve Dağıstan, doğuda Hārezm sınırlarına uzanan step bölgelerine kadar ge- nişletmiştir (Golden 1989: 147). -

KHAZAR TURKIC GHULÂMS in CALIPHAL SERVICE1 Arab

KHAZAR TURKIC GHULÂMS IN CALIPHAL SERVICE1 BY PETER B. GOLDEN Arab — Khazar relations, in particular their military confrontations for control of the Caucasus, have long been the subject of investigation. As a consequence of that sustained period of military encounters, the Khazars enjoyed a fierce reputation in the Islamic world. Thus, al-Balâd- hurî, in his comments on the massacre of some of the populace of MawÒil (Mosul) in the aftermath of the ‘Abbâsid takeover in 133/750, says that “because of their evil, the people of Mosul were called the Khazars of the Arabs.”2 Much less studied is one of the side-products of those wars: the presence of Khazars in the Caliphate itself. As with other peoples captured in warfare or taken or purchased on the periphery of the Caliphate, the Khazars in the Islamic heartlands were largely, but not exclusively, used as professional military men, slave-soldiers of the Caliphs, usually termed ghilmân (sing. ghulâm, lit. “boy, servant, slave”3). The relationship of these aliens to the larger Arab and Arabized 1 I would like to thank Michael Bates and Matthew Gordon for their thoughtful read- ings of this paper. Needless to say, I alone am responsible for any remaining errors or failure to take their advice. An earlier, non-updated Russian version of this article (“Khazarskie tiurkskie guliamy na sluzhbe Khalifata) is in press in Moscow, to be pub- lished in Khazary, Trudy Vtorogo Mezhdunarodnogo kollokviuma, ed. by I.A. Arzhant- seva, V.Ia. Petrukhin and A.M. Fedorchuk. 2 This passage is cited and translated in C.F. -

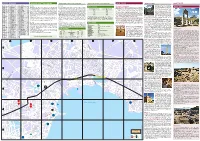

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Ai Margini Dell'impero. Potere E Aristocrazia a Trebisonda E in Epiro

Università del Piemonte Orientale Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici Dottorato di ricerca in ‘Linguaggi, storia e istituzioni’, curriculum storico Coordinatore: Referente per il curriculum: Ch.mo Prof. Claudio Marazzini Ch.mo Prof. Claudio Rosso Anno Accademico 2016/2017, XXIX ciclo Ai margini dell’Impero. Potere e aristocrazia a Trebisonda e in Epiro nel basso medioevo Tesi di dottorato in storia medievale, SSD M-STO/01 Tutor: Candidato: Ch.ma Prof.sa Germana Gandino Dott. Marco Fasolio 1 Indice Introduzione, p. 5 Per un profilo storico dell’aristocrazia bizantina, p. 11 Il dibattito storiografico, p. 22 1. Affari di famiglie. Trebisonda e il Ponto da Basilio II il Bulgaroctono alla quarta crociata, p. 45 1.1 Cenni storico-geografici su Trebisonda e la Chaldia, p. 45 1.2 Potere e aristocrazia in Chaldia prima della battaglia di Manzicerta, p. 48 1.3 Da Teodoro Gabras ad Andronico Comneno: l’alba del particolarismo pontico, p. 73 1.3.1 I primi Gabras, p. 74 1.3.2 Il progenitore dell’autonomia ponitca: Teodoro Gabras e il suo tempo, p. 79 1.3.3 I discendenti di Teodoro Gabras tra potere locale, servizio imperiale e intese con i Turchi, p. 93 1.3.4 Da principi armeni a magnati pontici, il caso dei Taroniti, p. 110 1.3.5 La Chaldia dopo Costantino Gabras: i Comneni e il ritorno dell’Impero, p. 123 1.4 Potere e aristocrazia nel Ponto prima del 1204: uno sguardo d’insieme, p. 135 2. Un covo di ribelli e di traditori. L’Epiro e le isole ionie tra l’XI secolo e il 1204, p. -

T.C. Firat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dali Malazgirt Öncesi Kafkasya'da Türk Varliği

T.C. FIRAT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI MALAZGİRT ÖNCESİ KAFKASYA'DA TÜRK VARLIĞI DOKTORA TEZİ DANIŞMAN HAZIRLAYAN Prof. Dr. M. Beşir AŞAN Zekiye TUNÇ ELAZIĞ - 2012 T.C. FIRAT ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANA BİLİM DALI MALAZGİRT ÖNCESİ KAFKASYA'DA TÜRK VARLIĞI DOKTORA TEZİ DANIŞMAN HAZIRLAYAN Prof. Dr. M. Beşir AŞAN Zekiye TUNÇ Jürimiz, ………tarihinde yapılan tez savunma sınavı sonunda bu yüksek lisans / doktora tezini oy birliği / oy çokluğu ile başarılı saymıştır. Jüri Üyeleri: 1. Prof. Dr. 2. 3. 4. 5. F. Ü. Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Yönetim Kurulunun …... tarih ve …….sayılı kararıyla bu tezin kabulü onaylanmıştır. Prof. Dr. Erdal AÇIKSES Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürü II ÖZET Doktora Tezi Malazgirt Öncesi Kafkasya’da Türk Varlığı Zekiye TUNÇ Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı Genel Türk Tarihi Bilim Dalı Elazığ – 2012, Sayfa: XVI+176 Kafkasya Karadeniz ile Hazar Denizi arasında doğu-batı paralelinde uzanan ve yüksekliği orta kısımlarda beş bin metreyi aşan bölgeye verilen addır. Kuzey-güney ve doğu-batı yollarının birleştiği bölgede olması nedeniyle etnik açıdan farklı kavimlerin uğrak yeri olmuştur. Türkler, Kafkasya’ya ana yurtları olan Asya’dan gelmişlerdir. Kafkasya bölgesinde M.Ö.4000’lere tarihlenen bozkır kültürünü temsil eden kurganların Asya’dan gelen göçerler tarafından oluşturulduklarına dair çalışmalar yapılmıştır. M.Ö.2000’lere gelindiğinde Proto-Türk olarak kabul edilen kabilelerin Kafkasya bölgesine geldikleri ve miladın başlarına kadar burada hâkim oldukları görülmüştür. Kronolojik olarak bakıldığında M.Ö.2000 yıllarının başlarından M.Ö.8. yy’a kadar Kimmerlerin, M.Ö.8. yy’dan M.Ö.2.yy’la kadar İskitlerin, sonrasında ise Sarmatların aynı coğrafyada varlıkları tespit edilmiştir.