POUL RUDERS Viola Concerto · Handel Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sponsorship Effects on Music Festival Participants

Copenhagen Business School 2014 MSoc.Sc.Service Management MASTER’S THESIS Sponsorship Effects on Music Festival Participants Victor Guedon David Gramm Kristensen February, 5th, 2014 Supervisor Helle Haurum 111 Pages / 267.755 Characters Abstract While worldwide investments in sole sponsorship fees were expected to reach $53.3 billion in 2013, findings from the academic research on sponsorships’ ability to impact customers’ perception of a sponsor are inconsistent; ranging from positive, small or ambiguous effects to negative or no effects at all. Thus, the objective of the current research was to contribute by researching if participation in a music festival, NorthSide 2013, would influence festival participants’ perception of the main sponsor Royal Beer. To do so, the chosen research design was a pre-post event quasi experimental design with independent samples. It was crucial to have both pre and post event measurements of event participants to investigate a potential change. Moreover, the quasi-experimental strategy was deemed relevant since it features the use of a control group to identify the source of an effect. Identified as one of the reasons for the inconsistent academic findings, the aim was to avoid conscious processing of the respondents by eliciting sponsorships or the two entities together, so that answers collected would account for the effects rather than respondents’ opinions about how this sponsorship affected them. In pursuance of this research several practical steps have been undertaken: a thorough literature review, a face-to-face interview of the Royal Beer brand manager, creation of a beer brand personality scale fitted to the Danish setting, a focus group to translate the brand personality facets and most importantly; the design and data collection of three distinct questionnaires that resulted in a total of 950 valid responses. -

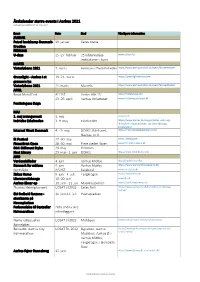

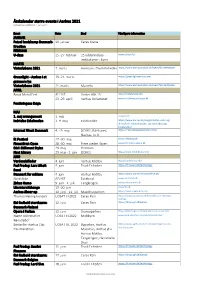

Eventkalender 2021, Webversion Maj 2021.Xlsx

Årskalender større events i Aarhus 2021 Webversion opdateret 10. maj 2021 Event Dato Sted Yderligere information JANUAR Futsal landskamp Danmark‐ 30. januar Ceres Arena Kroatien FEBRUAR U‐days 25.‐27. februar 25 uddannelses‐ www.udays.dk/ institutioner i byen MARTS Vinterløbene 2021 7. marts Hermans i Tivoli Friheden https://www.aarhusmotion.dk/event/WinterMaster Greenlight ‐ Aarhus i et 19.‐21. marts https://greenlightaarhus.com/ grønnere lys Vinterløbene 2021 21. marts Marselis https://www.aarhusmotion.dk/event/WinterMaster APRIL Royal Metal Fest AFLYST Vester Allé 15 http://metalroyale.dk/ 23.‐29. april Aarhus Universitet www.forskningensdoegn.dk Forskningens Døgn MAJ 1. maj arrangement 1. maj www.lo.dk Indvielse Eskelunden 3.‐9. maj Eskelunden https://www.aarhus.dk/borger/kultur‐natur‐og‐ idraet/ud‐i‐naturen/parker‐og‐skove/besoeg‐ eskelunden/ Internet Week Denmark 4. ‐ 9. maj DOKK1, Rådhuset, https://internetweekdenmark.com/ Navitas, m.fl. Ilt Festival 27.‐30. maj www.iltfestival.dk Firmaidræt Open 28.‐30. maj Flere steder i byen www.firmaidraetopen.dk DM i Different Styles 29. maj Hermans Next Library 29. maj ‐ 2. juni DOKK1 http://www.nextlibrary.net/ JUNI Verdensbilleder 4. juni Aarhus Midtby http://aarhus‐city.dk/ Danmark for målene 4. juni Aarhus Midtby https://www.danmarkformaalene.dk/ NorthSide AFLYST Eskelund www.northside.dk Zirkus Nemo 9. juni ‐ 4. juli Tangkrogen www.zirkus‐nemo.dk LiteratureXchange 10.‐20. juni www.litx.dk Aarhus åbner op 10. juni ‐ 11. juli Musikhusparken https://aarhusaabnerop.dk/ Thomas Helmig koncert UDSAT til 2022 Ceres Park https://www.parkarena.dk/kalender/juni/thomas‐ helmig/ EM fodbold fanzone ‐ 11. juni‐11. -

DENMARK “Very Tropical Again! You Can Hear That African Lo-Fi Influence on the Whole Album” - Gilles Peterson / BBC Radio 6 Music

WEST-AFRICAN FUNK, ELECTRO RAVE AND JAZZ IMPROVISATION DENMARK “Very tropical again! You can hear that African lo-fi influence on the whole album” - Gilles Peterson / BBC Radio 6 Music. DISCOGRAPHY: What kind of music would emerge if you combined a pair of renowned Danish MASALA, 2016 electronic producers with two of the most exciting jazz musicians around? RUMP RECORDINGS This was the question in the minds of the Copenhagen Strøm Festival curators. The answer? It arrived in the form of Scandinavian electro pioneers Rumpistol and Winner of Danish Music Awards Spejderrobot—two prominent characters with a reputation well beyond their home 2017: Best Danish Special Release countries—along with guitarist Niclas Knudsen and drummer/percussionist Emil de Waal. These four talented strangers, introduced with minimal rehearsal time, WAHwaHwa, 2016 were brought together and launched onstage, and KALAHA was born. A daring Rump Recordings experiment to say the least. From the spontaneous and infectious magic of their first show came their critically Digital EP acclaimed debut album “Hahaha”, the sound taking its inspiration in equal parts from West-African funk, electro rave and jazz improvisation, standing up as best possible blending of musical worlds—highly energetic and expressive, triggering QUARQUABA, 2016 the listener to dance with the head just as much as the heart. Rump Recordings Their four releases to date have proved to be captivating experiences, epitomized by their distinctive sound design as well as the outstanding instrumental Digital EP contributions of the protagonists. It comes as no surprise that their albums not only gather constant acclaim in among vinyl connoisseurs, but have also brought KALAHA a Danish Music Award in 2017 as well as a place on the playlists of numerous European radio stations. -

Rock Festival Safety Table of Contents

M I N I S T E R I E T Rock Festival Safety Report published by the Working Group set up by the Danish Government to Study the Safety Aspects of Music Festivals Published by: The Ministry of Culture, Post Box 2140 Nybrogade 2 DK-1015 Copenhagen K Tel: +45 33 92 33 70 Fax: + 45 33 91 33 88 e-mail: [email protected] homepage: www.kum.dk December 2000 This report may be carried freely subject to quotation of source Production: Sangill Grafisk Produktion Copies of this report are available on request from The Ministry of Culture, Post Box 2140 Nybrogade 2 DK-1015 Copenhagen K Tel: +45 33 92 35 00 Circulation: 600 ISBN: 87-7960-001-8 Electronic ISBN: 87-7960-002-6 Table of contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 THE ROSKILDE ACCIDENT (BASED ON THE PRELIMINARY REPORT ISSUED BY THE ROSKILDE POLICE DEPARTMENT, 14 JULY 2000) ........................................................................................ 5 1 TERMS OF REFERENCE................................................................................................................ 5 TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE WORKING GROUP SET UP TO STUDY THE SAFETY ASPECTS OF MUSIC FESTIVALS ....................................................................................................................... 5 DISTINGUISHING DANISH MUSIC FESTIVALS AND SIMILAR MAJOR MUSIC EVENTS FROM OTHER EVENTS .................................................................................................................................................6 -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

EJF Brochure2013 PRINT Layout 1

www.edinburghjazzfestival.com 19 - 28 July 2013 Jazz and Blues of all styles, for all ages, and appealing to everyone, will take over the centre of Edinburgh for 10 days from July 19-28, as the 35th Edinburgh Jazz and Blues Festival comes back to town for another celebration of good time, old time, funky, swinging, cutting edge, dance, intense art, total relaxation... There’ll be great nights out at Festival Theatre, party atmospheres at the Spiegeltent, top performers playing at the Queen’s Hall, a cool new modern jazz club at 3 Bristo Place, a traditional haven at the Royal Overseas League, an all day Festival club at the Tron Kirk, and a new programme strand – Cross the Tracks – where the Festival checks in to musics on, or just over the stylistic border. This brochure gives you the full programme and there are more details at www.edinburghjazzfestival.com. Among many highlights are the Edinburgh Jazz Festival Orchestra presenting the inspirational concert of Sacred Music by Duke Ellington; the great American pianist and singer Champian Fulton making her festival debut, one of a host of young players of classic jazz styles; Muddy Waters’ Centenary with his son Mud Morganfield, and we welcome, amazingly for the first time The 3 Bs with Chris Barber, Acker Bilk and, taking the place of his father, Kenny Ball, sadly departed: Keith Ball. The Festival gets the summer Festival season started with a bang, by bringing colour, music and entertainment to the streets and parks of Edinburgh, presenting The Mardi Gras and The Edinburgh Festival Carnival. -

Europe's White Working Class Communities in Aarhus

EUROPE’S WHITE WORKING CLASS COMMUNITIES 1 AARHUS AT HOME IN EUROPE EUROPE’S WHITE WORKING CLASS COMMUNITIES AARHUS OOSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.inddSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.indd CC11 22014.11.06.014.11.06. 118:40:328:40:32 ©2014 Open Society Foundations This publication is available as a pdf on the Open Society Foundations website under a Creative Commons license that allows copying and distributing the publication, only in its entirety, as long as it is attributed to the Open Society Foundations and used for noncommercial educational or public policy purposes. Photographs may not be used separately from the publication. ISBN: 9781940983189 Published by OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS 224 West 57th Street New York NY 10019 United States For more information contact: AT HOME IN EUROPE OPEN SOCIETY INITIATIVE FOR EUROPE Millbank Tower, 21-24 Millbank, London, SW1P 4QP, UK www.opensocietyfoundations.org/projects/home-europe Design by Ahlgrim Design Group Layout by Q.E.D. Publishing Printed in Hungary. Printed on CyclusOffset paper produced from 100% recycled fi bres OOSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.inddSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.indd CC22 22014.11.06.014.11.06. 118:40:348:40:34 EUROPE’S WHITE WORKING CLASS COMMUNITIES 1 AARHUS THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WORK TO BUILD VIBRANT AND TOLERANT SOCIETIES WHOSE GOVERNMENTS ARE ACCOUNTABLE TO THEIR CITIZENS. WORKING WITH LOCAL COMMUNITIES IN MORE THAN 100 COUNTRIES, THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS SUPPORT JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS, FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, AND ACCESS TO PUBLIC HEALTH AND EDUCATION. OOSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.inddSF_AARHUS_cimnegyed-1106.indd 1 22014.11.06.014.11.06. 118:40:348:40:34 AT HOME IN EUROPE PROJECT 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements This city report was prepared as part of a series of reports titled Europe’s Working Class Communities. -

Beslutningsreferat Kulturarrangementspuljen 2

Beslutningsreferat Kulturarrangementspuljen 2. puljerunde 2018 (2019 og 2020) Sagsnr. Sagsbehandler Ansøger Titel Ansøgtbeløb Ansøgtbeløb Ansøgtbeløb Ansøgtbeløb i Bevillinger Bevillinger Bevillinger Indstilling 2018 2019 2020 alt 2018 2019 2020 6570 Amanda Christmas Reach Out For A Child Pan African Festival Denmark 80.000 0 0 80.000 25.000 0 0 Der ydes tilskud til honorar til professionelle medvirkende til (AC) Pan African Festival, hvis formål er at udbrede viden om Afrika. Det forventes, at festivalen stadigt vil nå en stor målgruppe, også udenfor Aarhus Kommune. Det er glædeligt at se, at tilskuerantallet er steget støt siden 2015. 6620 Amanda Christmas Njyd Quartet NJYD.NYT.NORDISK 12.000 0 0 12.000 0 0 0 Afslag (AC) 6630 Amanda Christmas SI Århus Kraka African Women & Modern Design 30.000 0 0 30.000 0 0 0 Afslag (AC) 6632 Amanda Christmas Mikkel Egelund Nielsen Be:tween:sides 12.000 0 0 12.000 0 0 0 Afslag (AC) 6689 Amanda Christmas Ubuntu community Ubuntu Sommerfest 2018 300.120 0 0 300.120 25.000 0 0 Ubuntu Sommerfest har igen i år et spændende (AC) samarbejde, og vi kan se, at I ønsker at udbrede kendskabet til Sommerfesten ved at satse på et større publikum, blandt andet ved at invitere Værestedet Hus Forbi, Kultur og kontaktstedet Kragelund, Socialforvaltningen, og Socialpsykiatrien Katrinebjergvej – Center for Dagområdet Socialforvaltningen. Kulturarrangementspuljen støtter gerne Ubuntu Sommerfest i at blive en endnu større - og nu 2 dages festival. 6558 Anne Mette New Music for Strings New Music for Strings festival 200.000 0 0 200.000 50.000 0 0 New Music for Strings Festival er en ambitiøs festival med Svenningsen (AMS) 2018 koncerter, internationale samarbejder og outreach aktiviteter. -

Eventkalender 2021, Webversion Juni 2021.Xlsx

Årskalender større events i Aarhus 2021 Webversion opdateret 2. juni 2021 Event Dato Sted Yderligere information JANUAR Futsal landskamp Danmark‐ 30. januar Ceres Arena Kroatien FEBRUAR U‐days 25.‐27. februar 25 uddannelses‐ www.udays.dk/ institutioner i byen MARTS Vinterløbene 2021 7. marts Hermans i Tivoli Friheden https://www.aarhusmotion.dk/event/WinterMaster Greenlight ‐ Aarhus i et 19.‐21. marts https://greenlightaarhus.com/ grønnere lys Vinterløbene 2021 21. marts Marselis https://www.aarhusmotion.dk/event/WinterMaster APRIL Royal Metal Fest AFLYST Vester Allé 15 http://metalroyale.dk/ 23.‐29. april Aarhus Universitet www.forskningensdoegn.dk Forskningens Døgn MAJ 1. maj arrangement 1. maj www.lo.dk Indvielse Eskelunden 3.‐9. maj Eskelunden https://www.aarhus.dk/borger/kultur‐natur‐og‐ idraet/ud‐i‐naturen/parker‐og‐skove/besoeg‐ eskelunden/ Internet Week Denmark 4. ‐ 9. maj DOKK1, Rådhuset, https://internetweekdenmark.com/ Navitas, m.fl. Ilt Festival 27.‐30. maj www.iltfestival.dk Firmaidræt Open 28.‐30. maj Flere steder i byen www.firmaidraetopen.dk DM i Different Styles 29. maj Hermans Next Library 29. maj ‐ 2. juni DOKK1 http://www.nextlibrary.net/ JUNI Verdensbilleder 4. juni Aarhus Midtby http://aarhus‐city.dk/ Fed Fredag: Lars Lilholt 4. juni Tivoli Friheden https://friheden.dk/fed‐fredag/ Band Danmark for målene 4. juni Aarhus Midtby https://www.danmarkformaalene.dk/ NorthSide AFLYST Eskelund www.northside.dk Zirkus Nemo 9. juni ‐ 4. juli Tangkrogen www.zirkus‐nemo.dk LiteratureXchange 10.‐20. juni www.litx.dk Aarhus åbner op 10. juni ‐ 11. juli Musikhusparken https://aarhusaabnerop.dk/ Thomas Helmig koncert UDSAT til 2022 Ceres Park https://www.parkarena.dk/kalender/juni/thomas‐ helmig/ EM fodbold storskærm: 12. -

SYSTEM BORGER AARHUSKOMPASSET Mindre System

AARHUSKOMPASSET AARHUS – Mindre system. Mere borger Mere system. Mindre KOMPASSET – + 2020 SYSTEM BORGER AARHUSKOMPASSET Mindre system. Mere borger Copyright © 2020 Tænketanken Mandag Morgen Ny Kongensgade 10 DK – 1472 København K Tlf.: 33 93 93 23 Web: www.taenketanken.mm.dk Tænketanken Mandag Morgen Jonatan Porsager, projektchef (projektleder) Lisbeth Knudsen, tværgående chefredaktør Maria Rosenbeck Kvorning, senioranalytiker Design Mette Funck Redigering Susanne Sayers, Journalistik Med Mere Korrektur Ulf Houe, txt Redigering og korrektur Foto Side 8: Per Ryolf Side 31, 49, 65: Claus Peter Hastrup Side 46: Claus Sjödin Side 60: Rasmus Rasborg Tryk Grafisk Service Kultur og Borgerservice Aarhus Kommune ISBN 978-87-93038-70-7 AARHUSKOMPASSET Mindre system. Mere borger INDHOLD Forord 6 Det nye Aarhus: Mindre system, mere borger 9 Sådan finder du rundt 16 Nye veje til at lytte 24 Borgeren sætter dagsordenen 26 Værktøjet: Mennesketavler 30 Ståstedet: På vippebrættet mellem siloerne 32 Nye veje til at løse 36 Der skal være liv, når banken lukker kl. 17.00 38 Her skaber mennesker værdi for hinanden 44 Værktøjet: READ 48 Ståstedet: Mellem rammer og risikovillighed 51 Nye veje til at lære 54 Aarhus putter beta i betalingen 56 Når børn og unge bliver et fælles anliggende 62 Værktøjet: Effektvurderinger 68 Ståstedet: Et vindue for læring 70 Nye veje til at lede 74 Et mini-Aarhus satte nye mål for kommunen 76 Værktøjet: WHO-5 82 Ståstedet: At turde betræde nye veje 84 Ståstedet: En frihed fyldt med dilemmaer 87 Sådan er Aarhuskompasset blevet til 89 FORORD Med debatoplæggene Kærlig Kommune fra 2013 og Kommune Forfra fra 2015 indfangede Aarhus Kommune og Tænketanken Mandag Morgen sammen en række væsentlige forandringer i samspillet mellem kom- munen og det omgivende samfund. -

Instagram Som Dokumentations- Og Indsamlingsmetode

Nordisk Museologi 2015 • 1, s. 73–90 Instagram som dokumentations- og indsamlingsmetode Eksperimenter med brugerskabt fotodokumentation Martin Brandt Djupdræt, Christian Rasmussen, Lisbeth Skjernov & Anne Krøyer Sørensen Title: Instagram as a documentation and collecting method. Experiments with user-generated photo documentation Abstract: Instagram is a worldwide photo-sharing app for smartphones. Every day, users share more than 70 million photos and videos. Based on existing research on Instagram and other social media, this article describes and compares two specific projects implemented in the museum Den Gamle By (The Old Town) in Aarhus, Denmark, in 2013 and 2014, in which the museum has used Instagram as a tool for contemporary documentation. Keywords: Instagram, contemporary documentation, social media, photo documentation, collecting methods. Instagram er en verdensomspændende billed- medier generelt, beskrives og sammenlignes i delings-app til smartphones, som i december denne artikel to konkrete projekter, hvor Insta- 2014 kunne melde om 300 millioner aktive gram er benyttet til indsamling af samtidsdo- brugere på månedsbasis. Hver dag bliver mere kumentation. Resultaterne viser, at der er gode end 70 millioner billeder og videoer delt. In- muligheder i at bruge Instagram i museernes stagram så dagens lys i 2010, og siden da er indsamlings- og dokumentationsarbejde. over 20 milliarder billeder blevet delt via app’en (Systrom 2014). Museet Den Gamle By i Aar- Forskning i Instagram og sociale hus, Danmark, har i 2013 og 2014 afprøvet for- medier skellige metoder til at inddrage dette medie i museets forsknings- og indsamlingsarbejde Der er gennem de senere år opstået et stort inden for samtidsdokumentation. Med bag- forskningsfelt for museumsforskere i sociale grund i den eksisterende forskning i Instagram medier, men kun en mindre del af forskningen samt relevante aspekter af forskningen i sociale har fokuseret specifikt på den relativt nye bil- Martin Brandt Djupdræt et al. -

Ais Pta Handbook a Practical Guide to Living in Aarhus

AIS PTA HANDBOOK A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO LIVING IN AARHUS Edited by: AIS Parent Teacher Association Version 2.0 10/08/2020 INDEX TRANSPORTATION ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 CYCLING .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 BUS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 LETBANEN ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 TRAIN .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 FERRY .............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 DRIVING IN AARHUS / DENMARK ................................................................................................................................... 5 DRIVING LICENCE ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 PARKING ........................................................................................................................................................................