Europe's White Working Class Communities in Aarhus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Århus Distriktsforening Hvem Er Vi

Århus Distriktsforening Hvem er vi Århus Distriktsforening består af 53 menighedsråd i de fire provstier i Århus, hvor alle menighedsråd i Århus Dom Provsti, Århus Nordre Provsti, Århus Søndre Provsti og Århus Vestre Provsti er medlemmer. Distriktsforeningen varetager menighedsrådenes interesser og fremmer deres indbyrdes samarbejde og tilbyder ydelser efter lokale behov. I dette informationshæfte finder du navn, og kontaktmulighed for alle medlems sogne. Der er også en kort beskrivelse af arbejdsopgaver der kan iværksættes af Distriktsforeningen, samt orientering om den demokratiske struktur for Landsforeningen, Distriktsforeninger og Menighedsråd der udgør hele or- ganisationen. 99 % af Menighedsråd i Den Danske folkekirke er medlem af Landsforeningen og samtidig medlem af en Distriktsforening. Landsforeningen af Menighedsråd. Landsforeningen har deres administration i Sabro ved Århus og ledes af et sekretariat der yder hjælp og rådgivning til Menighedsråd og distriktsfore- ninger. Foreningens bestyrelse består af 20 valgte medlemmer, hvoraf 14 er læge medlemmer og 6 præster der alle er valgt af foreningens øverste myndighed. Den øverste myndighed er de valgte delegerede, der er valgt på en distrikts- forenings generalforsamling. Antallet af delegerede udgør 400 personer. Landsforeningen afholder årsmøde hvert år på Nyborg Strand i maj/juni måned. Årsmødet indeholder det årlige besluttende delegeretmøde. Landsforeningen udgiver et medlemsblad, der udkommer 10 gange årligt, og omdeles til menighedsrådsmedlemmer. Landsforeningen tilbyder gennem sin kursusvirksomhed aktuelle kurser der målrettet henvender sig menighedsrådsmedlemmer med specifikke op- gaver. Og den støtter Distriktsforeninger gennem uddannelse af bestyrelser. Valg af delegerede Alle delegerede til årsmødet på Nyborg Strand vælges på generalforsamlingen i Distriktsforeningen. Valget gælder for 1. år. Generalforsamlingen afholdes ifølge vedtægterne inden 1. -

Fællesrådenes Adresser

Fællesrådenes adresser Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail Kirkebakken 23 Beder-Malling-Ajstrup Fællesråd Jørgen Friis Bak [email protected] 8330 Beder Langelinie 69 Borum-Lyngby Fællesråd Peter Poulsen Borum 8471 Sabro [email protected] Holger Lyngklip Hoffmannsvej 1 Brabrand-Årslev Fællesråd [email protected] Strøm 8220 Brabrand Møllevangs Allé 167A Christiansbjerg Fællesråd Mette K. Hagensen [email protected] 8200 Aarhus N Jeppe Spure Hans Broges Gade 5, 2. Frederiksbjerg og Langenæs Fællesråd [email protected] Nielsen 8000 Aarhus C Hastruptoften 17 Fællesrådet Hjortshøj Landsbyforum Bjarne S. Bendtsen [email protected] 8530 Hjortshøj Poul Møller Blegdammen 7, st. Fællesrådet for Mølleparken-Vesterbro [email protected] Andersen 8000 Aarhus C [email protected] Fællesrådet for Møllevangen-Fuglebakken- Svenning B. Stendalsvej 13, 1.th. Frydenlund-Charlottenhøj Madsen 8210 Aarhus V Fællesrådet for Aarhus Ø og de bynære Jan Schrøder Helga Pedersens Gade 17, [email protected] havnearealer Christiansen 7. 2, 8000 Aarhus C Gudrunsvej 76, 7. th. Gellerup Fællesråd Helle Hansen [email protected] 8220 Brabrand Jakob Gade Øster Kringelvej 30 B Gl. Egå Fællesråd [email protected] Thomadsen 8250 Egå Navn Modtager af post Adresse E-mail [email protected] Nyvangsvej 9 Harlev Fællesråd Arne Nielsen 8462 Harlev Herredsvej 10 Hasle Fællesråd Klaus Bendixen [email protected] 8210 Aarhus Jens Maibom Lyseng Allé 17 Holme-Højbjerg-Skåde Fællesråd [email protected] -

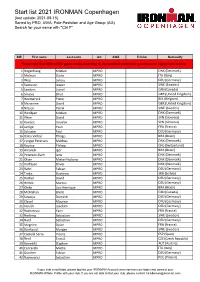

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

Business Plan Content

2020 Business plan Content Preface .................................................................................. 3 Business strategy ................................................................... 4 Framework for Aarhus Vand ................................................... 8 Cooperation with Aarhus Municipality ................................... 10 Annual wheel 2020 .............................................................. 12 The Board ............................................................................ 13 Purpose, vision and core story ............................................. 15 Strategic partnerships strengthen us ................................... 16 Integrating the UN’s global goals for sustainability ................ 20 Aarhus ReWater – a trailblazer in resource utilisation ............ 22 Implementing a digital transformation ................................... 24 New ways of working with water .......................................... 27 Creating a strong corporate culture together ........................ 28 Organisation ........................................................................ 30 Sharpened focus on financing .............................................. 32 Financial forecast for 2020 ................................................... 33 Investment and tariffs ........................................................... 34 Lars Schrøder, CEO Aarhus Vand 2 PREFACE Welcome to Aarhus Vand’s business plan Welcome to Aarhus Vand’s business plan. The 2020, we will therefore experiment -

Oversigt Over Retskredsnumre

Oversigt over retskredsnumre I forbindelse med retskredsreformen, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2007, ændredes retskredsenes numre. Retskredsnummeret er det samme som myndighedskoden på www.tinglysning.dk. De nye retskredsnumre er følgende: Retskreds nr. 1 – Retten i Hjørring Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten i Aalborg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Randers Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Aarhus Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Viborg Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Holstebro Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Herning Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Horsens Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Kolding Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Esbjerg Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Sønderborg Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Odense Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Svendborg Retskreds nr. 14 – Retten i Nykøbing Falster Retskreds nr. 15 – Retten i Næstved Retskreds nr. 16 – Retten i Holbæk Retskreds nr. 17 – Retten i Roskilde Retskreds nr. 18 – Retten i Hillerød Retskreds nr. 19 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. 20 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 21 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 22 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 23 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 24 – Retten på Bornholm Indtil 1. januar 2007 havde retskredsene følende numre: Retskreds nr. 1 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Gentofte Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Gladsaxe Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Ballerup Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Hvidovre Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Rødovre Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Brøndbyerne Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Taastrup Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Tårnby Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. -

Aarhus Kommune Forudsætninger for Forventet Regnskab Efter

Aarhus Kommune Forventet regnskab 1. kvartal 2018 Forventet Forventet forbrug i % af regnskab, regnskab, Aarhus Kommune Budget 2018 Forbrug Difference budget 0. kvartal 1. kvartal 2018 2018 Busdrift 219101 Kørselsudgifter 423.334.000 118.069.734 28% 431.469.512 438.908.000 15.574.000 219105 Bus IT og øvrige udgifter 8.949.000 1.823.492 20% 8.525.000 15.428.000 6.479.000 219501 Rejsekort - busser 17.415.000 3.671.072 21% 17.464.000 16.894.000 -521.000 219120 Indtægter -256.931.000 -67.712.827 26% -256.931.000 -257.890.000 -959.000 219125 Regionalt tilskud 0 0 0 0 0 I alt 192.767.000 55.851.471 29% 200.527.512 213.340.000 20.573.000 Flextrafik 219920 Handicapkørsel 13.474.000 2.478.091 18% 13.474.000 13.278.000 -196.000 219922 Flexture 983.000 236.655 24% 983.000 983.000 0 219924 Flexbus 0 0 0 0 0 219926 Kommunal kørsel 5.013.200 1.052.788 21% 4.499.600 4.232.000 -781.200 I alt 19.470.200 3.767.534 19% 18.956.600 18.493.000 -977.200 Tog og Letbane 219405 Letbanedrift 57.900.000 -936.691 -2% 41.011.000 40.053.500 -17.846.500 219820 Letbanesekretariatet 223.000 55.750 25% 223.000 223.000 0 Rejsekort - Letbanen 3.002.000 519.005 17% 2.996.000 2.941.000 -61.000 Administration og Øvrige 219801 Trafikselskabet 36.599.000 9.149.750 25% 36.599.000 36.599.000 0 219930 Billetkontrol 8.189.000 3.092.805 38% 8.189.000 9.264.000 1.075.000 219890 Tjenestemandspensioner 508.000 99.111 20% 501.510 502.000 -6.000 Total - netto 318.658.200 71.598.736 22% 309.003.622 321.415.500 2.757.300 Regnskab 2017 til afregning i 2019 ** 225.784 ** Positiv = skyldigt beløb - negativ = tilgodehavende Forudsætninger for forventet regnskab efter 1. -

The Committee of the Regions and the Danish Presidency of the Council of the European Union 01 Editorial by the President of the Committee of the Regions 3

EUROPEAN UNION Committee of the Regions The Committee of the Regions and the Danish Presidency of the Council of the European Union 01 Editorial by the President of the Committee of the Regions 3 02 Editorial by the Danish Minister for European Aff airs 4 03 Why a Committee of the Regions? 6 Building bridges between the local, the regional and 04 the global - Danish Members at work 9 05 Danish Delegation to the Committee of the Regions 12 06 The decentralised Danish authority model 17 EU policy is also domestic policy 07 - Chairmen of Local Government Denmark and Danish Regions 20 08 EU-funded projects in Denmark 22 09 The 5th European Summit of Regions and Cities 26 10 Calendar of events 28 11 Contacts 30 EUROPEAN UNION Committee of the Regions Editorial by the President of 01 the Committee of the Regions Meeting the challenges together We have already had a taste of Danish culture via NOMA, recognised as the best restaurant in the world for two years running by the UK’s Restaurants magazine for putting Nordic cuisine back on the map. Though merely whetting our appetites, this taster has confi rmed Denmark’s infl uential contribution to our continent’s cultural wealth. Happily, Denmark’s contribution to the European Union is far more extensive and will, undoubtedly, be in the spotlight throughout the fi rst half of 2012! A modern state, where European and international sea routes converge, Denmark has frequently drawn on its talents and fl ourishing economy to make its own, distinctive mark. It is in tune with the priorities for 2020: competitiveness, social inclusion and the need for ecologically sustainable change. -

Social Capital in Gellerup

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Journal of social inclusion. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Espvall, M., Laursen, L. (2014) Social capital in Gellerup. Journal of social inclusion, 5(1): 19-42 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:miun:diva-23812 Social capital in Gellerup ___________________________________________ Line Hille Laursen Psychiatric Research Unit West Denmark Majen Espvall Mid-Sweden University Abstract This paper examines the characteristics of two types of social capital; bridging and bonding social capital among the residents inside and outside a marginalized local community in relation to five demographic features of age, gender, geographical origin and years of residence in the community and in Denmark. The data were collected through a questionnaire, conducted in the largest marginalized high-rise community in Denmark, Gellerup, which is about to undergo an extensive community renewal plan. The study showed that residents in Gellerup had access to bonding and bridging social capital inside and outside Gellerup. Nevertheless, the character of the social capital varied considerably depending on age, geographical origin and years lived in Gellerup. Young residents and people who had lived for many years in Gellerup had more social capital than their counterparts. Furthermore, residents from Arab countries had more bonding relations inside Gellerup, while residents from Northern Europe had more bonding relations outside Gellerup. Keywords: Social capital, marginalized communities, Denmark, bonding social capital, bridging social capital Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Journal of Social Inclusion, 5(1), 2014 Introduction During the 1960s and 1970s, communities of large-scale high-rise housing estates were built in many countries to meet the after-war housing shortage. -

Case Study: Aarhus

European Union European Regional Development Fund MP4 Case study report Place-keeping in Aarhus Municipality, Denmark: Improving green space management by engaging citizens Andrej Christian Lindholst Forest and Landscape University of Copenhagen, Denmark May 2010 Aarhus, Denmark 2 MP4 WP1.3 Transnational Assessment of Practice Content Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Context ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Green spaces............................................................................................................................................ 3 Green space planning and management................................................................................................... 3 Green space maintenance ........................................................................................................................ 4 A ‘red’ circle ............................................................................................................................................. 5 The Project .................................................................................................................................................. 5 The park development plan ..................................................................................................................... -

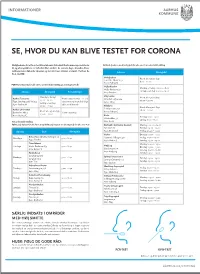

Testmuligheder I Aarhus Kommune

INFORMATIONER SE, HVOR DU KAN BLIVE TESTET FOR CORONA Mulighederne for at få en test bliver løbende forbedret. Der kommer nye teststeder Kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år uden tidsbestilling til, og åbningstiderne er forbedret flere steder i de seneste dage. Desuden bliver testkapaciteten løbende tilpasset og sat ind, hvor smitten er størst. Her kan du Adresse Åbningstid få et overblik: Nobelparken Åbent alle ugens dage Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2 8.00 – 20.00 8000 Aarhus C PCR-Test (I halsen) for alle over 2 år med tidsbestilling på coronaprover.dk Vejlby-Risskov Mandag – fredag: 06.00 – 18.00 Vejlby Centervej 51 Lørdag – søndag: 09.00 – 19.00 Adresse Åbningstid Bemærkninger 8240 Risskov Mandag – fredag: Viby Hallen Aarhus Testcenter Handicapparkering er på Åbent alle ugens dage 07.00 – 21.00 Skanderborgvej 224 Tyge Søndergaards Vej 953 testcentret og man skal følge 08.00 – 20.00 Lørdag – søndag: 8260 Viby J 8200 Aarhus N skiltene til kørende 08.00 – 21.00 Filmbyen Åbent alle ugens dage Aarhus Universitet Filmbyen Studie 1 Åbent alle ugens dage 08.00 – 20.00 Bartholins Allé 3 Handicapvenlig 8000 Aarhus C 09.00 – 16.00 8000 Aarhus C Beder Torsdag: 11:00 - 19:00 Kirkebakken 58 Lørdag: 11:00 - 17:00 Test uden tidsbestilling. 8330 Beder PCR test (i halsen for alle fra 2 år og kviktest (i næsen med kort pind) for alle over 6 år. Brabrand - Det Gamle Gasværk Mandag: 09.00 – 19.00 Byleddet 2C Tirsdag: 09.00 – 19.00 Ugedag Sted Åbningstid 8220 Brabrand Fredag: 09.00 – 19.00 Harlev Onsdag: 09:00 - 19:00 Beboerhuset Vest’n, Nyringen 1A Mandage 9.00 - 16.30. -

Ét Danmark Uden Parallelsamfund. Ingen Ghettoer I 2030

Ét Danmark uden parallelsamfund Ingen ghettoer i 2030 MARTS 2018 ÉT DANMARK UDEN PARALLELSAMFUND – INGEN GHETTOER I 2030 3 Indhold Ét Danmark uden parallelsamfund – Ingen ghettoer i 2030 4 Ny, markant og målrettet strategi mod parallelsamfund 7 1. Fysisk nedrivning og omdannelse af udsatte boligområder 10 Fysisk forandrede boligområder 11 Nye muligheder for fuld afvikling af de mest udsatte ghettoområder 14 Adgang til at opsige lejere ved salg af almene boliger i udsatte boligområder 14 2. Mere håndfast styring af hvem der kan bo i udsatte boligområder 17 Stop for kommunal anvisning til udsatte boligområder for ydelsesmodtagere 17 Obligatorisk fleksibel udlejning i udsatte boligområder 18 Lavere ydelse for tilflyttere i ghettoområder 18 Stop for tilflytning af modtagere af integrationsydelse 19 Kontant belønning til kommuner, der lykkes med integrationsindsatsen 19 3. Styrket politiindsats og højere straffe skal bekæmpe kriminalitet og skabe mere tryghed 22 Styrket politiindsats i særligt udsatte boligområder 22 Højere straffe i bestemte områder (skærpet strafzone) 23 Kriminelle ud af ghettoerne 23 4. En god start på livet for alle børn og unge 24 Obligatorisk dagtilbud skal sikre bedre danskkundskaber inden skolestart 24 Bedre fordeling i daginstitutioner 25 Målrettede sprogprøver i 0 klasse 26 Sanktioner over for dårligt præsterende folkeskoler 27 Styrket forældreansvar gennem mulighed for bortfald af børnecheck og et enklere forældrepålæg 27 Bedre fordeling af elever på gymnasier 28 Kriminalisering af genopdragelsesrejser 29 Hårdere kurs over for vold i hjemmet 29 Tidlig opsporing af udsatte børn 30 Skærpet straf for brud på den særligt udvidede underretningspligt 30 Regeringen følger op på indsatserne mod parallelsamfund 32 Bilag 1. -

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg Mod Sjælland Ca

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ København Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Roskilde Hillerød Helsingør Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Næstved Vordingborg Nykøbing F Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Korsør Slagelse Sorø Ringsted Køge Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Fyn Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 200 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aarhus ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Viborg Silkeborg ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Holstebro Herning ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Esbjerg Kolding Fredericia ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Skanderborg Horsens Vejle ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Sønderborg Aabenraa Haderslev ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ København Afg mod Jylland ca.