Sponsorship Effects on Music Festival Participants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Green Man Festival As a Case Study

An Investigation to identify how festivals promotional techniques have developed over the years – using Green Man Festival as a case study Victoria Curran BA (hons) Events Management Cardiff Metropolitan University April 2018 i Declaration “I declare that this Dissertation has not already been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. It is the result of my own independent research except where otherwise stated.” Name: Victoria Curran Signed: ii Abstract This research study was carried out in order to explore the different methods of marketing that Green Man Festival utilises, to discover how successful they are, and whether they have changed and developed throughout the years. The study intended to critically review the literature surrounding festivals and festival marketing theories, in order to provide conclusions supported by theory when evaluating the effectiveness of the promotional strategies. It aimed to discover how modern or digital marketing affected Green Man’s promotional techniques, to assess any identified promotional techniques and identify any connections with marketing theory, to investigate how they promote the festival towards their target market, and to finally provide recommendations for futuristic methods of promotion. The dissertation was presented coherently, consisting of five chapters. The first chapter was the introduction, providing a basic insight into the topics involved. The second contains a critical literature review where key themes were identified; the third chapter discussed the methodology used whilst the fourth chapter presents the results that were discovered, providing an analysis and discussion. The final chapter summarises the study, giving recommendations and identifying any limitations of the study. -

Thehard DATA Summer 2015 A.D

FFREE.REE. TheHARD DATA Summer 2015 A.D. EEDCDC LLASAS VEGASVEGAS BASSCONBASSCON & AAMERICANMERICAN GGABBERFESTABBERFEST REPORTSREPORTS NNOIZEOIZE SUPPRESSORSUPPRESSOR INTERVIEWINTERVIEW TTHEHE VISUALVISUAL ARTART OFOF TRAUMA!TRAUMA! DDARKMATTERARKMATTER 1414 YEARYEAR BASHBASH hhttp://theharddata.comttp://theharddata.com HARDSTYLE & HARDCORE TRACK REVIEWS, EVENT CALENDAR1 & MORE! EDITORIAL Contents Tales of Distro... page 3 Last issue’s feature on Los Angeles Hardcore American Gabberfest 2015 Report... page 4 stirred a lot of feelings, good and bad. Th ere were several reasons for hardcore’s comatose period Basscon Wasteland Report...page 5 which were out of the scene’s control. But two DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 factors stood out to me that were in its control, Noize Suppressor Interview... page 8 “elitism” and “moshing.” Th e Visual Art of Trauma... page 9 Some hardcore afi cionados in the 1990’s Q&A w/ CIK, CAP, YOKE1... page 10 would denounce things as “not hardcore enough,” Darkmatter 14 Years... page 12 “soft ,” etc. Th is sort of elitism was 100% anti- thetical to the rave idea that generated hardcore. Event Calendar... page 15 Hardcore and its sub-genres were born from the PHOTO CREDITS rave. Hardcore was made by combining several Cover, pages 5,8,11,12: Joel Bevacqua music scenes and genres. Unfortunately, a few Pages 4, 14, 15: Austin Jimenez hardcore heads forgot (or didn’t know) they came Page 9: Sid Zuber from a tradition of acceptance and unity. Granted, other scenes disrespected hardcore, but two The THD DISTRO TEAM wrongs don’t make a right. It messes up the scene Distro Co-ordinator: D.Bene for everyone and creativity and fun are the fi rst Arcid - Archon - Brandon Adams - Cap - Colby X. -

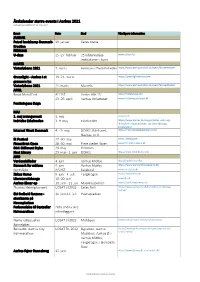

Eventkalender 2021, Webversion Maj 2021.Xlsx

Årskalender større events i Aarhus 2021 Webversion opdateret 10. maj 2021 Event Dato Sted Yderligere information JANUAR Futsal landskamp Danmark‐ 30. januar Ceres Arena Kroatien FEBRUAR U‐days 25.‐27. februar 25 uddannelses‐ www.udays.dk/ institutioner i byen MARTS Vinterløbene 2021 7. marts Hermans i Tivoli Friheden https://www.aarhusmotion.dk/event/WinterMaster Greenlight ‐ Aarhus i et 19.‐21. marts https://greenlightaarhus.com/ grønnere lys Vinterløbene 2021 21. marts Marselis https://www.aarhusmotion.dk/event/WinterMaster APRIL Royal Metal Fest AFLYST Vester Allé 15 http://metalroyale.dk/ 23.‐29. april Aarhus Universitet www.forskningensdoegn.dk Forskningens Døgn MAJ 1. maj arrangement 1. maj www.lo.dk Indvielse Eskelunden 3.‐9. maj Eskelunden https://www.aarhus.dk/borger/kultur‐natur‐og‐ idraet/ud‐i‐naturen/parker‐og‐skove/besoeg‐ eskelunden/ Internet Week Denmark 4. ‐ 9. maj DOKK1, Rådhuset, https://internetweekdenmark.com/ Navitas, m.fl. Ilt Festival 27.‐30. maj www.iltfestival.dk Firmaidræt Open 28.‐30. maj Flere steder i byen www.firmaidraetopen.dk DM i Different Styles 29. maj Hermans Next Library 29. maj ‐ 2. juni DOKK1 http://www.nextlibrary.net/ JUNI Verdensbilleder 4. juni Aarhus Midtby http://aarhus‐city.dk/ Danmark for målene 4. juni Aarhus Midtby https://www.danmarkformaalene.dk/ NorthSide AFLYST Eskelund www.northside.dk Zirkus Nemo 9. juni ‐ 4. juli Tangkrogen www.zirkus‐nemo.dk LiteratureXchange 10.‐20. juni www.litx.dk Aarhus åbner op 10. juni ‐ 11. juli Musikhusparken https://aarhusaabnerop.dk/ Thomas Helmig koncert UDSAT til 2022 Ceres Park https://www.parkarena.dk/kalender/juni/thomas‐ helmig/ EM fodbold fanzone ‐ 11. juni‐11. -

Preventing Drug-Related Deaths at Music Festivals: Why the "Rave" Act Should Be Amended to Provide an Exception for Harm Reduction Services

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 93 Issue 3 Comparative and Cross-Border Issues in Article 12 Bankruptcy and Insolvency Law 9-18-2018 Preventing Drug-Related Deaths at Music Festivals: Why the "Rave" Act Should be Amended to Provide an Exception for Harm Reduction Services Robin Mohr Chicago-Kent College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Robin Mohr, Preventing Drug-Related Deaths at Music Festivals: Why the "Rave" Act Should be Amended to Provide an Exception for Harm Reduction Services, 93 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 943 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol93/iss3/12 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PREVENTING DRUG-RELATED DEATHS AT MUSIC FESTIVALS: WHY THE “RAVE” ACT SHOULD BE AMENDED TO PROVIDE AN EXCEPTION FOR HARM REDUCTION SERVICES ROBIN MOHR INTRODUCTION Amid flashing lights and pulsing beats, nearly 100,000 electronic dance music fans attended Electric Zoo on New York’s Randall’s Island in August 2013.1 Unfortunately the party was cut short. Following the deaths of two young fans, the final day of the three-day music festival was can- celed at the request of city authorities.2 In separate incidents, Olivia Ro- tondo, a twenty-year-old University of New Hampshire student, and Jeffrey Russ, a twenty-three-year-old Syracuse University graduate,3 died after collapsing at Electric Zoo with high body temperatures.4 Toxicology results revealed that Ms. -

Is Rock Music in Decline? a Business Perspective

Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Helsinki Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration International Business and Logistics 1405484 22nd March 2018 Abstract Author(s) Jose Dailos Cabrera Laasanen Title Is Rock Music in Decline? A Business Perspective Number of Pages 45 Date 22.03.2018 Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Degree Programme International Business and Logistics Instructor(s) Michael Keaney, Senior Lecturer Rock music has great importance in the recent history of human kind, and it is interesting to understand the reasons of its de- cline, if it actually exists. Its legacy will never disappear, and it will always be a great influence for new artists but is important to find out the reasons why it has become what it is in now, and what is the expected future for the genre. This project is going to be focused on the analysis of some im- portant business aspects related with rock music and its de- cline, if exists. The collapse of Gibson guitars will be analyzed, because if rock music is in decline, then the collapse of Gibson is a good evidence of this. Also, the performance of independ- ent and major record labels through history will be analyzed to understand better the health state of the genre. The same with music festivals that today seem to be increasing their popularity at the expense of smaller types of live-music events. Keywords Rock, music, legacy, influence, artists, reasons, expected, fu- ture, genre, analysis, business, collapse, -

Rock Music Is a Genre of Popular Music That Entered the Mainstream in the 1950S

Rock music is a genre of popular music that entered the mainstream in the 1950s. It has its roots in 1940s and 1950s rock and roll, rhythm and blues, country music and also drew on folk music, jazz and classical music. The sound of rock often revolves around the electric guitar, a back beat laid down by a rhythm section of electric bass guitar, drums, and keyboard instruments such as Hammond organ, piano, or, since the 1970s, synthesizers. Along with the guitar or keyboards, saxophone and blues-style harmonica are sometimes used as soloing instruments. In its "purest form", it "has three chords, a strong, insistent back beat, and a catchy melody."[1] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, rock music developed different subgenres. When it was blended with folk music it created folk rock, with blues to create blues-rock and with jazz, to create jazz-rock fusion. In the 1970s, rock incorporated influences from soul, funk, and Latin music. Also in the 1970s, rock developed a number of subgenres, such as soft rock, glam rock, heavy metal, hard rock, progressive rock, and punk rock. Rock subgenres that emerged in the 1980s included new wave, hardcore punk and alternative rock. In the 1990s, rock subgenres included grunge, Britpop, indie rock, and nu metal. A group of musicians specializing in rock music is called a rock band or rock group. Many rock groups consist of an electric guitarist, lead singer, bass guitarist, and a drummer, forming a quartet. Some groups omit one or more of these roles or utilize a lead singer who plays an instrument while singing, sometimes forming a trio or duo; others include additional musicians such as one or two rhythm guitarists or a keyboardist. -

ISSUE B SS 2020 Your Personal White Space (Aaaahh Breathing Room...)

ART + CULT ISSUE B SS 2020 your personal white space (aaaahh breathing room...) verbose və:’bəʊs adj. using or expressed in more words than are needed. 2 the_verbose issue b : bipolar spring 2020 the_verbose On the eve of this release, the world was forced to shelter in place. As I clicked “publish” and closed my laptop, little did I know what awaited me in the morning: a global crisis that would soon reveal itself as the harbinger for existential crisis (I know), and social and political movements as businesses and communities simultaneously dismantled to come together. The bipolarity of this fueled the hyper connectivity between physical and digital space which was the core of this second issue back in early 2019 as I set out to map global intersections through art. In a quest to identify the common threads in vastly different mediums, messages, cultures and geographies, we can now reflect on the creative intelligence breeding change and elevating the human spirit in an uncertain and transient world. This second issue, b, represents bipolar. Through travel and serendipitous encounters, I’ve been documenting creativity to build a narrative around the visible confluence of human interaction from polar opposite worlds. wuuuut? The result: a curation of art + culture that collectively guide us out of emotional cues and robotic reactions, adrenaline and apathy lacing swipes and likes, and towards stories inviting us to look beyond the pictures, and respond with questions, and with intention. My interviews get personal in effort to decrease the distance between people and the pages, print or pixel. -

Psychobilly Psychosis and the Garage Disease in Athens

IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 5 – Issue 1 – Spring 2020 Psychobilly Psychosis and the Garage Disease in Athens Michael Tsangaris, University of Piraeus, Greece Konstantina Agrafioti, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece Abstract The complexity and the bizarre nature of Psychobilly as a music genre and as a music collectivity make it very convenient for reconsidering several views in relation to subcultures, neo-tribes and scenes. More specifically, the case of Greek Psychobilly can categorically present how subcultural trends can be disseminated across gender, social classes and national borders. This study aims to trace historically the scene of Psychobilly in Athens based on typical ethnographic research and analytic autoethnography. The research question is: Which are the necessary elements that can determine the existence of a local music scene? Supported by semi-structured interviews, the study examines how individuals related to the Psychobilly subculture comprehend what constitutes the Greek Psychobilly scene. Although it can be questionable whether there ever was a Psychobilly scene in Athens, there were always small circles in existence into which people drifted and stayed for quite a while, constituting the pure core of the Greek Psychobilly subculture. Keywords: psychobilly, music genres, Athens, Post-subcultural Theory 31 IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 5 – Issue 1 – Spring 2020 Introduction According to the American Countercultures Encyclopaedia, Psychobilly is a subculture that emerged in the 1980s from the unlikely combination of rockabilly and punk rock. The provocative and sometimes outrageous style associated with psychobillies (also known as “psychos”) mixes the blue-collar rawness and rebellion of 1950s rockabilly with the confrontational do-it-yourself style of 1970s punk rock, a syncretism infused with themes from monster and horror films, campy sci-fi movies, and even professional wrestling” (Wojcik, 2013, p. -

Do Ticketmaster's Exclusive Agreements with Concert Venues Violate Federal Antitrust Law?

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 10 Issue 2 Volume 10, Spring 1995, Issue 2 Article 7 "Not for You"; Only for Ticketmaster: Do Ticketmaster's Exclusive Agreements with Concert Venues Violate Federal Antitrust Law? Matthew K. Finkelstein Colleen Lagan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "NOT FOR YOU";, ONLY FOR TICKETMASTER: DO TICKETMASTER'S EXCLUSIVE AGREEMENTS WITH CONCERT VENUES VIOLATE FEDERAL ANTITRUST LAW? America's antitrust laws are premised upon the belief that com- petition fosters the best allocation of resources within a given in- dustry.2 Lower prices, higher output, and better product quality that result from vigorous competition 3 are desirable from both so- cial and economic perspectives.4 The inherent conflict in applying antitrust law is that an effi- cient or innovative company may drive competitors out of busi- ness.5 A question then arises as to whether the dominant firm may have violated antitrust law simply because, through effi- 1 PEARL JAm, Not For You, on VrrALOGy (Sony Records 1994). 2 See National Soc'y of Professional Eng'rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 695 (1978). In Professional Eng'rs, the Court stated that "[t]he Sherman Act reflects a legislative judg- ment that ultimately competition will produce lower prices, but better goods and services." Id.; see also Northern Pac. -

DENMARK “Very Tropical Again! You Can Hear That African Lo-Fi Influence on the Whole Album” - Gilles Peterson / BBC Radio 6 Music

WEST-AFRICAN FUNK, ELECTRO RAVE AND JAZZ IMPROVISATION DENMARK “Very tropical again! You can hear that African lo-fi influence on the whole album” - Gilles Peterson / BBC Radio 6 Music. DISCOGRAPHY: What kind of music would emerge if you combined a pair of renowned Danish MASALA, 2016 electronic producers with two of the most exciting jazz musicians around? RUMP RECORDINGS This was the question in the minds of the Copenhagen Strøm Festival curators. The answer? It arrived in the form of Scandinavian electro pioneers Rumpistol and Winner of Danish Music Awards Spejderrobot—two prominent characters with a reputation well beyond their home 2017: Best Danish Special Release countries—along with guitarist Niclas Knudsen and drummer/percussionist Emil de Waal. These four talented strangers, introduced with minimal rehearsal time, WAHwaHwa, 2016 were brought together and launched onstage, and KALAHA was born. A daring Rump Recordings experiment to say the least. From the spontaneous and infectious magic of their first show came their critically Digital EP acclaimed debut album “Hahaha”, the sound taking its inspiration in equal parts from West-African funk, electro rave and jazz improvisation, standing up as best possible blending of musical worlds—highly energetic and expressive, triggering QUARQUABA, 2016 the listener to dance with the head just as much as the heart. Rump Recordings Their four releases to date have proved to be captivating experiences, epitomized by their distinctive sound design as well as the outstanding instrumental Digital EP contributions of the protagonists. It comes as no surprise that their albums not only gather constant acclaim in among vinyl connoisseurs, but have also brought KALAHA a Danish Music Award in 2017 as well as a place on the playlists of numerous European radio stations. -

Ticketmaster L.L.C

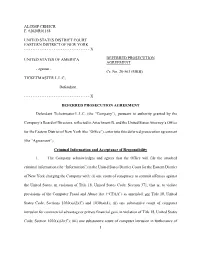

AL/DMP:CRH/ICR F. #2020R01158 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEFERRED PROSECUTION AGREEMENT - against - Cr. No. 20-563 (MKB) TICKETMASTER L.L.C., Defendant. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X DEFERRED PROSECUTION AGREEMENT Defendant Ticketmaster L.L.C. (the “Company”), pursuant to authority granted by the Company’s Board of Directors, reflected in Attachment B, and the United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York (the “Office”), enter into this deferred prosecution agreement (the “Agreement”). Criminal Information and Acceptance of Responsibility 1. The Company acknowledges and agrees that the Office will file the attached criminal information (the “Information”) in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York charging the Company with: (i) one count of conspiracy to commit offenses against the United States, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 371, that is, to violate provisions of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (“CFAA”) as amended, see Title 18, United States Code, Sections 1030(a)(2)(C) and 1030(a)(4); (ii) one substantive count of computer intrusion for commercial advantage or private financial gain, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 1030(a)(2)(C); (iii) one substantive count of computer intrusion in furtherance of 1 fraud, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 1030(a)(4); (iv) one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 1349; and (v) one substantive count of wire fraud, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 1343. -

Rock Festival Safety Table of Contents

M I N I S T E R I E T Rock Festival Safety Report published by the Working Group set up by the Danish Government to Study the Safety Aspects of Music Festivals Published by: The Ministry of Culture, Post Box 2140 Nybrogade 2 DK-1015 Copenhagen K Tel: +45 33 92 33 70 Fax: + 45 33 91 33 88 e-mail: [email protected] homepage: www.kum.dk December 2000 This report may be carried freely subject to quotation of source Production: Sangill Grafisk Produktion Copies of this report are available on request from The Ministry of Culture, Post Box 2140 Nybrogade 2 DK-1015 Copenhagen K Tel: +45 33 92 35 00 Circulation: 600 ISBN: 87-7960-001-8 Electronic ISBN: 87-7960-002-6 Table of contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 THE ROSKILDE ACCIDENT (BASED ON THE PRELIMINARY REPORT ISSUED BY THE ROSKILDE POLICE DEPARTMENT, 14 JULY 2000) ........................................................................................ 5 1 TERMS OF REFERENCE................................................................................................................ 5 TERMS OF REFERENCE OF THE WORKING GROUP SET UP TO STUDY THE SAFETY ASPECTS OF MUSIC FESTIVALS ....................................................................................................................... 5 DISTINGUISHING DANISH MUSIC FESTIVALS AND SIMILAR MAJOR MUSIC EVENTS FROM OTHER EVENTS .................................................................................................................................................6