The Ban Placed by the Community of Barcelona on the Study of Philosophy and Allegorical Preaching — a New Study*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TALMUDIC STUDIES Ephraim Kanarfogel

chapter 22 TALMUDIC STUDIES ephraim kanarfogel TRANSITIONS FROM THE EAST, AND THE NASCENT CENTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, SPAIN, AND ITALY The history and development of the study of the Oral Law following the completion of the Babylonian Talmud remain shrouded in mystery. Although significant Geonim from Babylonia and Palestine during the eighth and ninth centuries have been identified, the extent to which their writings reached Europe, and the channels through which they passed, remain somewhat unclear. A fragile consensus suggests that, at least initi- ally, rabbinic teachings and rulings from Eretz Israel traveled most directly to centers in Italy and later to Germany (Ashkenaz), while those of Babylonia emerged predominantly in the western Sephardic milieu of Spain and North Africa.1 To be sure, leading Sephardic talmudists prior to, and even during, the eleventh century were not yet to be found primarily within Europe. Hai ben Sherira Gaon (d. 1038), who penned an array of talmudic commen- taries in addition to his protean output of responsa and halakhic mono- graphs, was the last of the Geonim who flourished in Baghdad.2 The family 1 See Avraham Grossman, “Zik˙atah shel Yahadut Ashkenaz ‘el Erets Yisra’el,” Shalem 3 (1981), 57–92; Grossman, “When Did the Hegemony of Eretz Yisra’el Cease in Italy?” in E. Fleischer, M. A. Friedman, and Joel Kraemer, eds., Mas’at Mosheh: Studies in Jewish and Moslem Culture Presented to Moshe Gil [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1998), 143–57; Israel Ta- Shma’s review essays in K˙ ryat Sefer 56 (1981), 344–52, and Zion 61 (1996), 231–7; Ta-Shma, Kneset Mehkarim, vol. -

The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murder and Kabbalah: Seeds Of

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 4 (2009): Jospe R 1-4 REVIEW Lippman Bodoff The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murder and Kabbalah: Seeds of Jewish Extremism and Alienation? (Jerusalem and New York: Devora Publishing, 2005) Reviewed by Raphael Jospe, Bar Ilan University Twice every year, on Rosh Ha-Shanah and on the Sabbath, a few weeks later, when Genesis 22 is read as part of the annual cycle of reading the Torah in the synagogue, Jews are confronted by the drama of the Akedah, Abraham’s “binding” of Isaac in an ultimately aborted attempt to offer his beloved son as a sacrifice to God. On many Sabbaths, and on festivals when the Yizkor (memorial) prayers are recited, Ashkenazi Jews have the custom of reciting the Av Ha-Rahamim, an anonymous prayer from the thirteenth century commemorating Jewish communities martyred in Germany during the first Crusade. Masada, where, after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple, some 960 Jewish zealots and their families held off the Roman army and finally, facing the inevitable, committed mass suicide in 73 CE rather than surrender, is not merely a spectacular historical and archeological site; it has become a site of pilgrimage, where Israeli soldiers proclaim “Masada shall not fall again,” and where many youngsters celebrate their becoming Bar/Bat Mitzvah. The common thread to these three Jewish practices is what Lippman Bodoff calls “religious murder.” To offer one’s child as a sacrifice to God is murder. To kill one’s family and then commit suicide, even under extreme circumstances, as Jewish husbands and fathers did at Masada, and then a thousand years later in the face of Crusader mobs in the Rhineland (1096), and again a century later in York, England, on the Sabbath before Passover, 1190, is, Bodoff argues passionately, murder, and a violation of the moral teachings of Judaism. -

Hebrew Printed Books and Manuscripts

HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. SELECTIONS FROM FROM THE THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, MARCH 30TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 51 Catalogue of HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS . SELECTIONS FROM THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON Sold by Order of the Trustees The Third Portion (With Additions) To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 30th March, 2004 (NOTE CHANGE OF SALE DATE) at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 28th March: 10 am–5:30 pm Monday, 29th March: 10 am–6 pm Tuesday, 30th March: 10 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our new Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Winnington” Sale Number Twenty Three. Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) Hebrew Index Available on Request KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 ¥ Tel: 212 366-1197 ¥ Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] ¥ World Wide Web Site: www.kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Belazel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale, please contact: Daniel E. -

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies Table of Contents Ancient Jewish History .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Medieval Jewish History ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Modern Jewish History ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Bible .................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Jewish Philosophy ............................................................................................................................................... 23 Talmud ................................................................................................................................................................ 29 Course Catalog | Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies 1 Ancient Jewish History JHI 5213 Second Temple Jewish Literature Dr. Joseph Angel Critical issues in the study of Second Temple literature, including biblical interpretations and commentaries, laws and rules of conduct, historiography, prayers, and apocalyptic visions. JHI 6233 Dead Sea Scrolls Dr. Lawrence Schiffman Reading of selected Hebrew and Aramaic texts from the Qumran library. The course will provide students with a deep -

Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World

EJIW Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World 5 volumes including index Executive Editor: Norman A. Stillman Th e goal of the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World is to cover an area of Jewish history, religion, and culture which until now has lacked its own cohesive/discreet reference work. Th e Encyclopedia aims to fi ll the gap in academic reference literature on the Jews of Muslims lands particularly in the late medieval, early modern and modern periods. Th e Encyclopedia is planned as a four-volume bound edition containing approximately 2,750 entries and 1.5 million words. Entries will be organized alphabetically by lemma title (headword) for general ease of access and cross-referenced where appropriate. Additionally the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World will contain a special edition of the Index Islamicus with a sole focus on the Jews of Muslim lands. An online edition will follow aft er the publication of the print edition. If you require further information, please send an e-mail to [email protected] EJIW_Preface.indd 1 2/26/2009 5:50:12 PM Australia established separate Sephardi institutions. In Sydney, the New South Wales Association of Sephardim (NAS), created in 1954, opened Despite the restrictive “whites-only” policy, Australia’s fi rst Sephardi synagogue in 1962, a Sephardi/Mizraḥi community has emerged with the aim of preserving Sephardi rituals in Australia through postwar immigration from and cultural identity. Despite ongoing con- Asia and the Middle East. Th e Sephardim have fl icts between religious and secular forces, organized themselves as separate congrega- other Sephardi congregations have been tions, but since they are a minority within the established: the Eastern Jewish Association predominantly Ashkenazi community, main- in 1960, Bet Yosef in 1992, and the Rambam taining a distinctive Sephardi identity may in 1993. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

The Early Ibn Ezra Supercommentaries: a Chapter in Medieval Jewish Intellectual History

Tamás Visi The Early Ibn Ezra Supercommentaries: A Chapter in Medieval Jewish Intellectual History Ph.D. dissertation in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest April 2006 To the memory of my father 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 7 Prolegomena............................................................................................................................ 12 1. Ibn Ezra: The Man and the Exegete ......................................................................................... 12 Poetry, Grammar, Astrology and Biblical Exegesis .................................................................................... 12 Two Forms of Rationalism.......................................................................................................................... 13 On the Textual History of Ibn Ezra’s Commentaries .................................................................................. 14 Ibn Ezra’s Statement on Method ................................................................................................................. 15 The Episteme of Biblical Exegesis .............................................................................................................. 17 Ibn Ezra’s Secrets ....................................................................................................................................... -

124900176.Pdf

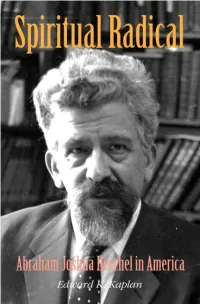

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

THE MAIMONIDEAN CONTROVERSY Dr

UNIT 7 DOES THE TORAH CONTAIN EVERYTHING WE NEED TO KNOW? THE MAIMONIDEAN CONTROVERSY Dr. Alan Mittleman I. MOSES OR ARISTOTLE: WAS THE WORLD CREATED FROM NOTHING OR IS IT ETERNAL? 1. Maimonides, Guide of the Perplexed, Volume II, Chapter 25, ed. and trans. Shlomo Pines: 114-117 II. RESPONSES TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL WORK OF MAIMONIDES 2. Shem Tov ibn Falaquera, Epistle of the Debate, ed. and trans. Steven Harvey: 17-21 3. Judah Alfakhar, Letter to David Kimhi, ed. Jacob Rader Marcus and Marc Saperstein: 531-533 4. Solomon ibn Adret (Rashba), Bans on the Study of Philosophy, ed. Jacob Rader Marcus and Marc Saperstein: 535-536 5. Michael Wyschogrod, The Body of Faith: 84-85 DOES THE TORAH CONTAIN EVERYTHING WE NEED TO KNOW? DR. ALAN MITTLEMAN Alan Mittleman is Aaron Rabinowitz and Simon H. Rifkind Professor of Jewish Philosophy at The Jewish Theological Seminary. His research and teaching focus on the intersection between Jewish thought and Western philosophy in the fields of ethics, political theory, and philosophy of religion. He is the author of eight books, most recently Does Judaism Condone Violence? Holiness and Ethics in the Jewish Tradition (Princeton, 2018) and Holiness in Jewish Thought (Oxford, 2018). His current book project is on the meaning of life in contemporary philosophical literature and Jewish thought. He has edited three books, and his many articles, essays, and reviews have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies. He has been a visiting professor or fellow at the University of Cologne, Harvard University, the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem, and Princeton University, and has received grants from the Yale Center for Faith and Culture and the Jack Miller Center. -

Download PDF Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s , gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a L ar t in cl u d i n g : th e Ca s s u t o Co ll e C t i o n o F ib e r i a n bo o K s , pa r t iii K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , Ju n e 21s t , 2012 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 261 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 21st June, 2012 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 17th June - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 18th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 19th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 20th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Galle” Sale Number Fifty Five Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . -

Copyright by Jane Robin Zackin 2008

Copyright by Jane Robin Zackin 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Jane Robin Zackin certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A JEW AND HIS MILIEU: ALLEGORY, POLEMIC, AND JEWISH THOUGHT IN SEM TOB’S PROVERBIOS MORALES AND MA’ASEH HA RAV Committee: ____________________________________ Matthew Bailey, Supervisor ____________________________________ Michael Harney ____________________________________ Madeline Sutherland-Meier ____________________________________ Harold Leibowitz ____________________________________ John Zemke A JEW AND HIS MILIEU: ALLEGORY, POLEMIC, AND JEWISH THOUGHT IN SEM TOB’S PROVERBIOS MORALES AND MA’ASEH HA RAV by Jane Robin Zackin, B.A.; M.ED.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2008 Knowledge is a deadly friend When no one sets the rules. King Crimson, “Epitaph” Acknowledgements I would like to thank the members of my committee for their help and encouragement, Dolores Walker for her ongoing support, and my father for his kind generosity. v A JEW AND HIS MILIEU: ALLEGORY, POLEMIC, AND JEWISH THOUGHT IN SEM TOB’S PROVERBIOS MORALES AND MA’ASEH HA RAV Publication No.____________________ Jane Robin Zackin, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin Supervisor: Matthew Bailey In this dissertation, I describe social, economic and political relations between Jews and Christians in medieval Europe before presenting the intellectual and religious context of Jewish life in Christian Spain. The purpose of this endeavor is to provide the framework for analyzing two works, one in Hebrew and one in Castilian, by the Spanish Jewish author Sem Tob de Carrión (1290- c.1370). -

F Ine J Udaica

F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, JUNE 29TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 340 Catalogue of F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART Including Judaic Ceremonial Art: From the Collection of Daniel M. Friedenberg, Greenwich, Conn. And a Collection of Holy Land Maps and Views To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 29th June, 2004 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 27th June: 10:00 am–5:30 pm Monday, 28th June: 10:00 am–6:00 pm Tuesday, 29th June: 10:00 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our New Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Sheldon” Sale Number Twenty Four. Illustrated Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Bezalel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale please contact: Daniel E. Kestenbaum ❧ ❧ ❧ ORDER OF SALE Printed Books: Lots 1 – 224 Manuscripts: Lots 225 - 271 Holy Land Maps: Lots 272 - 285 Ceremonial Art:s Lots 300 - End of Sale Front Cover: Lot 242 Rear Cover: A Selection of Bindings List of prices realized will be posted on our Web site, www.kestenbaum.net, following the sale.