The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murder and Kabbalah: Seeds Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected]

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Fall 12-2016 The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shaker, Christiane, "The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes" (2016). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2220. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2220 Seton Hall University THE “LAMB OF GOD” TITLE IN JOHN’S GOSPEL: BACKGROUND, EXEGESIS, AND MAJOR THEMES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEOLOGY CONCENTRATION IN BIBLICAL THEOLOGY BY CHRISTIANE SHAKER South Orange, New Jersey October 2016 ©2016 Christiane Shaker Abstract This study focuses on the testimony of John the Baptist—“Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” [ἴδε ὁ ἀµνὸς τοῦ θεοῦ ὁ αἴρων τὴν ἁµαρτίαν τοῦ κόσµου] (John 1:29, 36)—and its impact on the narrative of the Fourth Gospel. The goal is to provide a deeper understanding of this rich image and its influence on the Gospel. In an attempt to do so, three areas of concentration are explored. First, the most common and accepted views of the background of the “Lamb of God” title in first century Judaism and Christianity are reviewed. -

GOD's GREATEST SIN Rosh Hashanah Second Day October 1

GOD’S GREATEST SIN Rosh Hashanah Second Day October 1, 2019 2 Tishri 5780 Rabbi Jennifer R. Greenspan I have found, at least in my life, that we are often our own worst critics. We expect too much of ourselves, and we overuse the word “should,” trying desperately to reach some unattainable goal of perfection. I should be able to work a full-time job, maintain a clean home, cook and serve three healthy meals a day, and find at least an hour a day for exercise. I should be able to find time to meditate, go to bed earlier, get up earlier, still get eight hours of sleep, drink more water, and start a yoga routine. I should stop buying things I don’t need and be better about saving money. I should stop using disposable bottles, plastic straws, and eating anything that isn’t organic. I should come to synagogue more often. I should stop looking at my phone. I should use my phone to make sure I’m on top of my calendar. I should spend more time with my family. I should figure out how to be perfect already. How many of those “should”s that we constantly tell ourselves are really true to who we are, and how many come from a culture of perfectionism? When we are sitting in a season of judgement, how are we to judge ourselves and our deeds and our sins when we know we’re not perfect? In the Talmud, Rabbi Abbahu asks: Why on Rosh Hashanah do we sound a shofar made from a ram’s horn? אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא: תקעו לפני בשופר של איל כדי שאזכור לכם עקידת יצחק The Holy Blessed One said: use a shofar made from a ram’s horn, so that I will be reminded of the -

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies Table of Contents Ancient Jewish History .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Medieval Jewish History ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Modern Jewish History ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Bible .................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Jewish Philosophy ............................................................................................................................................... 23 Talmud ................................................................................................................................................................ 29 Course Catalog | Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies 1 Ancient Jewish History JHI 5213 Second Temple Jewish Literature Dr. Joseph Angel Critical issues in the study of Second Temple literature, including biblical interpretations and commentaries, laws and rules of conduct, historiography, prayers, and apocalyptic visions. JHI 6233 Dead Sea Scrolls Dr. Lawrence Schiffman Reading of selected Hebrew and Aramaic texts from the Qumran library. The course will provide students with a deep -

General Index

GENERAL INDEX Aaron, 73, 78, 275, 278 Bilhah, 88–89 Abraham, 64, 72, 77, 101–103, 171–172, Boaz, 290 204, 285–287, 289 Body, symbolism of, 22–23, 47, 108–109, Absalom, 165, 168, 171, 176, 178 162, 181, 259 Abtalon, 2 Burnt offering, 21, 124, 139, 210 Adam, 83, 103, 293 Adonijah, 178 Cain, 178, 181, 278 Adjuration, 79, 81, 84–91, 124–125, 133, Change and decline, 138, 167 Graeco-Roman approaches, 256–263 Adultery rabbinic approaches, 250–256, 262–263 and decline, 115, 255–259, 262–263 Children exposure of, 70–72, 76, 111–112, 167, illegitimate, 72, 219–220, 282–296 170, 287 qualities of, 216–219, 221–222, 284 and idolatry, 34–35, 47, 72–74, 211, resemblances of, 72, 286–287 270 Christianity, 19, 108–109, 165–166, 226, Christian perspectives on, 108–109, 284, 288–296 235 Confession, see Guilt, confession of Roman perspectives on, 39, 107–109, Contra Celsum, 288, 293, 295 116, 231, 258–259 Critical Approaches, 9–13, 271–272 and Ten Commandments, 283–284 Form Criticism, 12 in Temple precincts, 157–158 History of Traditions Approach, 12 Agag, 273 Redaction Criticism, 11 Agrippa, 44 Source Criticism, 11 Ahab, 189 Synoptic Approach, 11, 13 Ahashverosh, 201 Curse, see Oath and curse Ahitofel, 178 Akedah (binding of Isaac), 77, 284 David, King, 41, 88, 179, 289–290 Amalek, 276 Dead Sea Scrolls, 10, 154–156, 279–281 Amen, 123, 126, 129–137, 139, 215, 276 Dinah, 42 Amnon, 88, 189 Divorce, 39, 49–51, 54, 60–63, 137, Appian, 259–260 187–188, 224, 235, 252, 290, 294 Ashes, 98–99, 101–103, 140–147, 152, 157 Doeg, 178 Augustus, 259 Doras, 261 Avihu, -

Criticism of Religion and Child Abuse in the Video Game the Binding of Isaac

Tilburg University I Have Faith in Thee, Lord Bosman, Frank; van Wieringen, Archibald Published in: Religions DOI: 10.3390/rel9040133 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Bosman, F., & van Wieringen, A. (2018). I Have Faith in Thee, Lord: Criticism of Religion and Child Abuse in the Video Game the Binding of Isaac. Religions, 9(4), [133]. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040133 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. sep. 2021 religions Article I Have Faith in Thee, Lord: Criticism of Religion and Child Abuse in the Video Game the Binding of Isaac Frank G. Bosman 1,* and Archibald L. H. M. van Wieringen 2 1 Department of Systematic Theology and Philosophy, Tilburg University, 5037 AB Tilburg, The Netherlands 2 Department of Biblical Sciences and Church History, Tilburg University, 5037 AB Tilburg, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 26 March 2018; Accepted: 12 April 2018; Published: 16 April 2018 Abstract: The game The Binding of Isaac is an excellent example of a game that incorporates criticism of religion. -

The Early Ibn Ezra Supercommentaries: a Chapter in Medieval Jewish Intellectual History

Tamás Visi The Early Ibn Ezra Supercommentaries: A Chapter in Medieval Jewish Intellectual History Ph.D. dissertation in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest April 2006 To the memory of my father 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction............................................................................................................................... 7 Prolegomena............................................................................................................................ 12 1. Ibn Ezra: The Man and the Exegete ......................................................................................... 12 Poetry, Grammar, Astrology and Biblical Exegesis .................................................................................... 12 Two Forms of Rationalism.......................................................................................................................... 13 On the Textual History of Ibn Ezra’s Commentaries .................................................................................. 14 Ibn Ezra’s Statement on Method ................................................................................................................. 15 The Episteme of Biblical Exegesis .............................................................................................................. 17 Ibn Ezra’s Secrets ....................................................................................................................................... -

124900176.Pdf

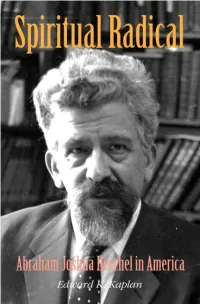

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

THE MAIMONIDEAN CONTROVERSY Dr

UNIT 7 DOES THE TORAH CONTAIN EVERYTHING WE NEED TO KNOW? THE MAIMONIDEAN CONTROVERSY Dr. Alan Mittleman I. MOSES OR ARISTOTLE: WAS THE WORLD CREATED FROM NOTHING OR IS IT ETERNAL? 1. Maimonides, Guide of the Perplexed, Volume II, Chapter 25, ed. and trans. Shlomo Pines: 114-117 II. RESPONSES TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL WORK OF MAIMONIDES 2. Shem Tov ibn Falaquera, Epistle of the Debate, ed. and trans. Steven Harvey: 17-21 3. Judah Alfakhar, Letter to David Kimhi, ed. Jacob Rader Marcus and Marc Saperstein: 531-533 4. Solomon ibn Adret (Rashba), Bans on the Study of Philosophy, ed. Jacob Rader Marcus and Marc Saperstein: 535-536 5. Michael Wyschogrod, The Body of Faith: 84-85 DOES THE TORAH CONTAIN EVERYTHING WE NEED TO KNOW? DR. ALAN MITTLEMAN Alan Mittleman is Aaron Rabinowitz and Simon H. Rifkind Professor of Jewish Philosophy at The Jewish Theological Seminary. His research and teaching focus on the intersection between Jewish thought and Western philosophy in the fields of ethics, political theory, and philosophy of religion. He is the author of eight books, most recently Does Judaism Condone Violence? Holiness and Ethics in the Jewish Tradition (Princeton, 2018) and Holiness in Jewish Thought (Oxford, 2018). His current book project is on the meaning of life in contemporary philosophical literature and Jewish thought. He has edited three books, and his many articles, essays, and reviews have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies. He has been a visiting professor or fellow at the University of Cologne, Harvard University, the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem, and Princeton University, and has received grants from the Yale Center for Faith and Culture and the Jack Miller Center. -

The Rebinding of Isaac: a Story of Survival and Revival

The Rebinding of Isaac: A Story of Survival and Revival Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica George A. Smathers Libraries University of Florida JANUARY 2017 In Memory of Jack Price 24th of Tevet 5777 The Rebinding of Isaac: A Story of Survival and Revival The Binding of Isaac The Spanish rabbi, philosopher and teacher, Isaac ben Moses Arama (c. 1420–1494) delivered many sermons on the principles of Judaism, providing great comfort to the Jewish community of Aragon, particularly during a period of increased pogroms and mass conversions. These sermons were later bound up into his opus magnum: Akedat Yitzhak (The Binding of Isaac) the title of which plays on the idea of a collectanea, as well as recalling the supreme sacrifice of Abraham in Genesis 22. Arama’s sermons covered a broad range of topics, including more philosophical discussions about the nature of the soul and the concept of free will. His unique style of sermonizing blended the moralistic didacticism of the Ashkenazi rabbinic academies with the philosophical proclivities of Provençal and Spanish Jewish scholars. 3 In his introduction, Arama explained that such an a Christian: one of the first and most prominent printers approach provided an urgently needed counterweight of Hebrew books, Daniel Bomberg. to the persuasive methods of those Christian preachers who “expound the doctrines of their faith as well as the words of the Bible in a philosophic and scholarly manner.” He advised that other rabbis adopt similar tactics in explaining and defending Judaism. The Binding of Isaac consists of 105 sermons based on verses from the Pentateuch, with each sermon divided into two parts: the derishah (investigation) and the perishah (exposition). -

Defeat Mom Using the Bible. the Controversial Debate in The

Defeat Mom U sing the Bible . The C ontroversial D ebate in The Binding of Isaac Isabell Gloria Brendel Abstract Review of the video game The Binding of Isaac concerning the controversial debate this game cause d among the gamers. Keywords: The Binding of Isaac , controversial debate, religious subject , gamevironments To cite this article: Brendel , I . G. , 2017 . Defeat Mom using the Bible. The controversial debat e in T he Binding of Isaac . gamevironments 7 , 77 - 86 . Available at http://www.gamevironments.uni - bremen.de . 77 _______ Introduction The creation of a good video game is not only a creative process. The financial aspect s are important as well. A well - known publisher guarantees an elaborate marketing for the upcoming game , ensuring that a great range of potential customers can be reached. However, most of the big publisher s refuse to release games with controversia l and sensi tive subjects, as for instance abuse, bullying, nudity or religion. But b esides publisher - supported games, there is another category of video game: The independent video game. Independent video games or “ indie ” games for the developers provide f reedom to make a game of their choices . With crowd - funding campaigns or a stable financial community support some of these games made the jump out of being lesser known to popular . One of the recent popular indie games is The Binding of Isaac . First released on 28th September 2011 on Steam, the game got great review scores and built its own community. In the years following 2011 , the game got some expansions and new versions, which added more items, characters, enemies, levels and endings to T he Binding of Isaac . -

F Ine J Udaica

F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, JUNE 29TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 340 Catalogue of F INE J UDAICA . HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS, MANUSCRIPTS &CEREMONIAL ART Including Judaic Ceremonial Art: From the Collection of Daniel M. Friedenberg, Greenwich, Conn. And a Collection of Holy Land Maps and Views To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 29th June, 2004 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 27th June: 10:00 am–5:30 pm Monday, 28th June: 10:00 am–6:00 pm Tuesday, 29th June: 10:00 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our New Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Sheldon” Sale Number Twenty Four. Illustrated Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Bezalel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale please contact: Daniel E. Kestenbaum ❧ ❧ ❧ ORDER OF SALE Printed Books: Lots 1 – 224 Manuscripts: Lots 225 - 271 Holy Land Maps: Lots 272 - 285 Ceremonial Art:s Lots 300 - End of Sale Front Cover: Lot 242 Rear Cover: A Selection of Bindings List of prices realized will be posted on our Web site, www.kestenbaum.net, following the sale. -

The Ban Placed by the Community of Barcelona on the Study of Philosophy and Allegorical Preaching — a New Study*

Ram BEN-SHALOM The Open University, Tel Aviv THE BAN PLACED BY THE COMMUNITY OF BARCELONA ON THE STUDY OF PHILOSOPHY AND ALLEGORICAL PREACHING — A NEW STUDY* RÉSUMÉ La mise au ban des études philosophiques imposée par Salomon ben Adret en 1305, constitue l'acmé d'une longue controverse entre le camp philosophique et ses oppo- sants en Provence et en Espagne. Une théorie récente suppose que Ben Adret avait tout d'abord imposé ce ban aux communautés juives d'Espagne et de Provence, puis avait changé d'avis, prétendant que ce bannissement était local, et n'était im- posé qu'à la seule communauté de Barcelone. On a prétendu aussi que cette volte face était la conséquence des relations politiques entre les royaumes de France et d'Aragon, et du conflit autour de l'épineuse question de la juridiction sur la juiverie provençale. Cet article réexamine l'affaire du ban à travers une analyse minutieuse des lettres publiées par Abba Mari de Lunel dans son ouvrage, «Minhat Qena'ot», et parvient à de nouvelles conclusions. Il commence par établir une distinction claire entre deux formes de ban. Le premier ban imposé sur les études philosophi- ques était en effet local, c'est pourquoi il a été maintenu par Ben Adret. Il existait également une deuxième forme de banissement de nature plus générale contre les hérésies et les hérétiques juifs. Il semble que le changement de position de Ben Adret a l'égard du second ban, ne résultait pas de sa crainte de possibles repré- sailles de Philippe le Bon, roi de France, contre les Juifs provençaux.