Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Victoria Annual Report 2017

annual repoRt 017 2 Including Music Victoria’s strategic summary and other documents with 2017 updates. contents Details of 2017 AGM 03 Minutes of 2016 AGM 05 Chair’s Report 09 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 12 Treasurer’s Report 14 About Us 16 Mission Statement and Vision 16 Strategic Plan 19 Key Achievements 2017 20 Music Victoria Staff 21 Music Victoria Advocacy 23 Music Victoria Board 24 Subcommittees Advisory Panels The Age Music Victoria Awards and The After Party 28 Professional Development Program The Age MV Awards Programs 30 Good Music Neighbours Live Music Professionals Victorian Music Crawl Financial Report 33 Page 02 DETAILS OF 2017 AGM The Annual General Meeting of Contemporary individual membership, and one vote if you have a Music Victoria Inc. (‘Music Victoria’) will be held band, small business, non-profit, corporate, gold at the offices of Music Victoria, Level 1, 49 Tope or platinum membership). Street, South Melbourne, Victoria, 3205 from 6:00pm sharp, Thursday 7 December 2017 (doors Members will be able to vote on the election of from 5.30pm). four (4) members to the Board. All current financial members of Music Victoria Members will also vote on amendments to the are welcome and encouraged to attend. If your Rules of Association of Music Victoria (‘Rules’), membership has lapsed, you must renew by namely updating the Rules to refer to committee Wednesday 22 November 2017 if you wish to members/directors of Music Victoria, collectively, attend or vote at the AGM. as ‘the Board’, instead of ‘Committee of Management’. Members of Music Victoria who are financial members as at 23 November 2017 are eligible Music Victoria annual reports and a copy of the to vote in the election of members of the proposed amended Rules will be circulated to Committee of Management (‘Board’). -

"A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2014 "A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes Sarah Taylor Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology Colin Arrowsmith Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, [email protected] Nicole T. Cook University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers Part of the Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Sarah; Arrowsmith, Colin; and Cook, Nicole T., ""A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes" (2014). Faculty of Social Sciences - Papers. 3071. https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/3071 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] "A Band on Every Corner": Using Historical GIS to Describe Changes in the Sydney and Melbourne Live Music Scenes Abstract This paper demonstrates the use of historical Geographic Information Systems (historical GIS) to investigate live music in Sydney and Melbourne. It describes the creation of a tailored historical geodatabase built from samples of gig listings (comprising dates, locations, and performer names), and how this historical geodatabase offers insight into the changing dynamics of performers and venue locations. The major findings from the analyses using the developed historical geodatabase are that neither city showed a decline in live music performance or performer numbers, but Melbourne increased at a greater rate than Sydney. -

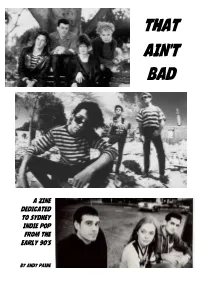

That Ain't Bad (The Main Single Off Tingles), the Band Are Drowned out by the Crowd Singing Along

THAT AIN’T BAD A ZINE DEDICATED TO SYDNEY INDIE POP FROM THE EARLY 90’S BY ANDY PAINE INTROduction In the late 1980's and early 1990's, a group of bands emerged from Sydney who all played fuzzy distorted guitars juxtaposed with poppy melodies and harmonies. They released some wonderful music, had a brief period of remarkable mainstream success, and then faded from the memory of Australia's 'alternative' music world. I was too young to catch any of this music the first time around – by the time I heard any of these bands the 90’s were well and truly over. It's hard to say how I first heard or heard about the bands in this zine. As a teenage music nerd I devoured the history of music like a mechanical harvester ploughing through a field of vegetables - rarely pausing to stop and think, somethings were discarded, some kept with you. I discovered music in a haphazard way, not helped by living in a country town where there were few others who shared my passion for obscure bands and scenes. The internet was an incredible resource, but it was different back then too. There was no wikipedia, no youtube, no streaming, and slow dial-up speeds. Besides the net, the main ways my teenage self had access to alternative music was triple j and Saturday nights spent staying up watching guest programmers on rage. It was probably a mixture of all these that led to me discovering what I am, for the purposes of this zine, lumping together as "early 90's Sydney indie pop". -

18 September 2002

ESTIMATES COMMITTEE PROCEEDINGS – 18 September 2002 CHIEF MINISTER In Committee in Continuation: Mr CHAIRMAN: Ladies and gentlemen, colleagues, it being 9 am, I propose that we continue this Estimates Committee. I reflected overnight, as I suppose most people have, about our progress. I will not go into that again. It is, in a way, a little like a cricket match. We really have to cooperate with one another to try to get through the two innings. A member: Is it a test match or a one day? Mr CHAIRMAN: No, this is a test match. We have a … Ms Martin: We could have penalties. Mr CHAIRMAN: Well, that is right. A member: We need five days then. Mr CHAIRMAN: Maybe. No, this is the Sheffield Shield. I would exhort everybody involved to try to get through our business as speedily as possible. We were aiming to have three ministers today. We are about half way through the Chief Minister and we still have the member for Nhulunbuy to go. By my estimation makes four-and-a-half. So let us go to it. The first business overhanging from last night was in relation to Output 03.10, which was the NT Railway. It has been confirmed to me that that will be dealt with by Minister Henderson. That leads us onto Output 04.10 which is Support to Executive, Ministers and Leader of the Opposition. Once again, the member for Brennan has asked most of the questions here and I put it in his hands. Mr WOOD: Mr Chairman, did you get a ruling on those questions about the railway … Dr Lim: 65 and 81. -

Songs About Perth

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Post 2013 2016 Nothing happens here: Songs about Perth Jon Stratton Independent Scholar, Perth, Australia Adam Trainer Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013 Part of the Australian Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons 10.1177/0725513616657884 This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of: Stratton, J., & Trainer, A. (2016), Nothing happens here: Songs about Perth. Thesis Eleven, 135(1), 34-50. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications. Available here This Journal Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013/2163 Nothing Happens Here: Songs About Perth Jon Stratton Adam Trainer Abstract This essay examines Perth as portrayed through the lyrics of popular songs written by people who grew up in the city. These lyrics tend to reproduce the dominant myths about the city, that it is isolated, that it is self-satisfied, that little happens there. Perth became the focus of song lyrics during the late 1970s time of punk with titles such as ‘Arsehole Of The Universe’ and ‘Perth Is A Culture Shock.’ Even the Eurogliders’ 1984 hit, ‘Heaven Must Be There,’ is based on a rejection of life in Perth. However, Perth was also home to Dave Warner whose songs in the 1970s and early 1980s offered vignettes, which is itself a title of one of Warner’s tracks, of the youthful, male suburban experience. The essay goes on to examine songs by the Triffids, Bob Evans, Sleepy Township and the Panda Band. Keywords: Perth; songs; music; place; isolation; lyrics Myths of the City Every city has its myths. -

Music Business and the Experience Economy the Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy

Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy . Peter Tschmuck • Philip L. Pearce • Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Editors Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Institute for Cultural Management and School of Business Cultural Studies James Cook University Townsville University of Music and Townsville, Queensland Performing Arts Vienna Australia Vienna, Austria Steven Campbell School of Creative Arts James Cook University Townsville Townsville, Queensland Australia ISBN 978-3-642-27897-6 ISBN 978-3-642-27898-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27898-3 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013936544 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

Résumé Date of Birth 1 October 1976, Tampere, Finland

Erkki Veltheim: Résumé Date of Birth 1 October 1976, Tampere, Finland Nationality Australian/Finnish Address 120 Garton Street, Princes Hill, VIC 3054 Telephone +61 (0)407 328 105 Email [email protected] Website erkkiveltheim.com Soundcloud soundcloud.com/erkkiveltheim Professional Appointments/Positions 2013-2016 Chamber Made Opera: Artistic Associate 2005- Australian Art Orchestra: Violinist, Violist, Electric Violinist 1998- ELISION Ensemble: Violist Academic history 2008-2010 Master of Arts, Victoria University 2002-2004 Bachelor of Arts and Sciences, University of Melbourne (not completed) 1999-2000 Postgraduate Diploma in Solo Studies, Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London 1995-1997 Bachelor of Music (Performance), Victorian College of the Arts Other educational programs 1996-1998 Australian National Academy of Music short courses Grants, Awards and Prizes 2019 Melbourne Prize for Music 'Distinguished Musicians Fellowship 2019' 2019 2018 Australian Music Prize (AMP) for Djarimirri by Gurrumul (co-composer, arranger, conductor) 2018 4 ARIA Awards for Djarimirri by Gurrumul (co-composer, arranger, conductor) 2014 Sidney Myer Creative Fellowship 2013 Australia Council for the Arts Project Fellowship 2013 Finalist in the Melbourne Music Prize Outstanding Musician of the Year Award 2010 Finalist in the Melbourne Music Prize Outstanding Musician of the Year Award 2008 Australian Postgraduate Award 2004 Dean's Award, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne 1999 Keith and Elizabeth Murdoch Traveling Fellowship (Victorian College -

“You Went There for the People and Went There for the Bands”

“You went there for the people and went there for the bands” The Sandringham Hotel – 1980 to 1998 Brendan Paul Smyly Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney August 2010 2 Acknowledgements I offer thanks to my supervisors, principally Dr Diana Blom whose knowledge, good advise and enthusiasm for a broad array of topics was invaluable for the length of this study. To Dr Greg Noble, a serendipitous choice who provided great counsel at the oddest hours and introduced me to whole vistas of academic view, thank you. Also to Professor Michael Atherton who offered unwavering support (along with some choice gigs) over the years of my engagement with UWS, many thanks. I offer very special thanks to all my colleagues from the Music Department at UWS. Ian Stevenson and Dr Sally Macarthur, thank you for your faith and support. To John Encarnacao, who was also an interviewee for the project, your advice and enthusiasm for the project has been invaluable and saw me through some difficult months, as has your friendship, thank you. To Mitchell Hart, your knowledge and willingness to help with myriad tasks whenever asked is greatly appreciated. My time as a student in this department will be fondly remembered due to you people being there. Many thanks to the administrative staff of the School of Communication Arts, particularly Robin Mercer for candidature funding and travel advice, and Tracy Mills at the Office of Research Service for your prompt and valuable help. Above all, I wish to thank Darinca Blajic. Thank you for your unfailing love, support and wonderful food. -

Glasshouse Musos All Reports

GLASSHOUSE MOUNTAINS MUSOS CLUB The first event for the Glasshouse Mountains Musos Club will be held on the Sunshine Coast at the Glasshouse Mountains Sports Club (on Steve Irwin Way), on Thursday May 12, from 7 – 10pm. The evening will be run in a blackboard style where performers either elect on the night, or book beforehand, to play for approximately 15 minutes. There will be spots at approximately 7, 7.20, 7.40, 9, 9.20 and 9.40pm with a feature act at 8pm. Artists will also be encouraged to promote their work through CD and other merchandise sales. Meals and of course drinks will be available at the venue. Weʼll provide good quality sound for the artists, and we encourage all styles of music, but with an emphasis on folk, blues, world, jazz and all forms of improvisation, country, bluegrass and theatre music. Please join us in encouraging music making in our region. Any level of support is welcome. The event will be further promoted through local venues, newspapers, community radio, music clubs and social media networks. Contact: Dr Michael Whiticker www.soundspace.com.au email [email protected] Mob. 0419026895 ********** GLASSHOUSE MOUNTAINS MUSOS CLUB May 12, 2011 Published in the GC News May 25 – page 12 (the review below) A great night was had by the 30 or so people who attended the inaugural Glasshouse Mountains Musos Club at the Sport Club last Thursday. Amongst the performers were Duo Classique (Craig and Joy), who included a magical performance of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, the rich harmonies of Champagne (Pam, Sue, Neil and Gerry), Leanne Zadkovitch, who shared five originals with us - which we’ll look forward to hearing again, Paul Fagan, who showed what a versatile singer / guitarist he is, a number of more than competent backing musicians who willingly got up to support us (thank you Neil for your harmonies and bass), and yours truly who presented some foot tappin’ “swamp rock”. -

A Beat for You Pseudo Echo a Day in the Life the Beatles a Girl Like

A Beat For You Pseudo Echo A Day In The Life The Beatles A Girl Like You Edwyn Collins A Good Heart Feargal Sharkey A Groovy Kind Of Love Phil Collins A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bryan Ferry A Kind Of Magic Queen A Little Less Conversation Elvis vs JXL A Little Ray of Sunshine Axiom A Matter of Trust Billy Joel A Sky Full Of Stars Coldplay A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton A Touch Of Paradise John Farnham A Town Called Malice The Jam A View To A Kill Duran Duran A Whiter Shade Of Pale Procol Harum Abacab Genesis About A Girl Nirvana Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Absolute Beginners David Bowie Absolutely Fabulous Pet Shop Boys Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Adam's Song Blink 182 Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Adventure of a Lifetime Coldplay Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers Affirmation Savage Garden Africa Toto After Midnight Eric Clapton Afterglow INXS Agadoo Black Lace Against All Odds (Take A Look At Me Now) Phil Collins Against The Wind Bob Seger Age of Reason John Farnham Ahead of Myself Jamie Lawson Ain't No Doubt Jimmy Nail Ain't No Mountain High Enough Jimmy Barnes Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine The Rockmelons feat. Deni Hines Alive Pearl Jam Alive And Kicking Simple Minds All About Soul Billy Joel All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All By Myself Eric Carmen All Fired Up Pat Benatar All For Love Bryan Adams, Rod Stewart & Sting All I Do Daryl Braithwaite All I Need Is A Miracle Mike & The Mechanics All I Wanna Do Sheryl Crow All I Wanna Do Is Make Love To You Heart All I Want -

Interrogating the Shaping of Sexual Identities Through the Digital Fan Spaces of the Eurovision Song Contest

‘Party for everybody’? Interrogating the shaping of sexual identities through the digital fan spaces of the Eurovision Song Contest J HALLIWELL PhD 2021 ‘Party for everybody’? Interrogating the shaping of sexual identities through the digital fan spaces of the Eurovision Song Contest JAMIE HALLIWELL A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Science and Engineering Manchester Metropolitan University 2021 ABSTRACT This research critically examines Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) fandom to explore how sexuality is shaped within digital fan spaces. Transformations in social media technologies have revolutionised ESC fan practices and what it means to be an ESC fan. I make a case for ESC fandom as a sprawling context through which its digital practices intersect with the performance of sexuality. This research uses a mixed- method approach, that involves experimenting with social media platforms as tools for conducting qualitative research. This includes developing and applying WhatsApp ‘group chats’ with ESC fans and an auto-netnography of my personal Twitter network of ESC fans. I contribute to the geographies of social media, fandom and sexuality in the following ways: I provide the first comprehensive analysis of the digital ecosystem of ESC fandom by mapping the online and offline fan spaces where ESC fandom is practiced. I argue that ESC fan spaces are fluid and dynamic and ESC fans travel between them. I then explore two social media platforms, Facebook and Twitter, to understand how ESC fans express, make visible, and negotiate their fan and sexual identities within and across these digital fan spaces. -

Life in a Padded Cell: a Biography of Tony Cohen, Australian Sound Engineer by Dale Blair ©Copyright

Life in a Padded Cell: A Biography of Tony Cohen, Australian Sound Engineer by Dale Blair ©copyright ~ One ~ Satan has possessed your Soul! ‘Tony is very devout in “God’s Lesson”. I cannot speak highly enough of Tony’s manners and behaviour. They are beyond reproach’. It was the sort of report card every parent liked to see. It was 1964. The Beatles were big and Tony Cohen was a Grade One student at St. Francis de Sales primary school, East Ringwood. The following year he took his first communion. The Beatles were still big and there seemed little to fear for the parents of this conscientious and attentive eight-year-old boy. The sisters who taught him at that early age would doubtless have been shocked at the life he would come to lead – a life that could hardly be described as devout. Tony Cohen was born on 4 June 1957 in the maternity ward of the Jessie MacPherson hospital in Melbourne. Now a place specializing in the treatment of cancer patients it was a general hospital then. He was christened Anthony Lawrence Cohen. His parents Philip and Margaret Cohen had been living in James Street, Windsor, but had moved to the outer eastern suburb of East Ringwood prior to the birth of their son. Philip Cohen was the son of Jewish immigrants who had left Manchester, England, and settled in Prahran, one of Melbourne’s inner eastern suburbs. Philip’s father had served in the First World War, survived and then migrated to Australia with his wife and infant son (Tony’s Uncle David).