“You Went There for the People and Went There for the Bands”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Into the Mainstream Guide to the Moving Image Recordings from the Production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988

Descriptive Level Finding aid LANDER_N001 Collection title Into the Mainstream Guide to the moving image recordings from the production of Into the Mainstream by Ned Lander, 1988 Prepared 2015 by LW and IE, from audition sheets by JW Last updated November 19, 2015 ACCESS Availability of copies Digital viewing copies are available. Further information is available on the 'Ordering Collection Items' web page. Alternatively, contact the Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to view the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on viewing The collection is open for viewing on the AIATSIS premises. AIATSIS holds viewing copies and production materials. Contact AFI Distribution for copies and usage. Contact Ned Lander and Yothu Yindi for usage of production materials. Ned Lander has donated production materials from this film to AIATSIS as a Cultural Gift under the Taxation Incentives for the Arts Scheme. Restrictions on use The collection may only be copied or published with permission from AIATSIS. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1988 Extent: 102 videocassettes (Betacam SP) (approximately 35 hrs.) : sd., col. (Moving Image 10 U-Matic tapes (Kodak EB950) (approximately 10 hrs.) : sd, col. components) 6 Betamax tapes (approximately 6 hrs.) : sd, col. 9 VHS tapes (approximately 9 hrs.) : sd, col. Production history Made as a one hour television documentary, 'Into the Mainstream' follows the Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi on its journey across America in 1988 with rock groups Midnight Oil and Graffiti Man (featuring John Trudell). Yothu Yindi is famed for drawing on the song-cycles of its Arnhem Land roots to create a mix of traditional Aboriginal music and rock and roll. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Theoretical Aspects. Service to the Major Parts of This 868-Item

1,0C t- T R F: AC 002 713 ED 023 024 By -Crew, Vernon Bibliography of Australian Adult Education,1835 -1965. Austriahan Association of AdultEducation, Melbourne.; National Librarya Australia, Canberra. Pub Date 68 Note I Up. EDRS Price MF -SOSO HC -S580 Industry, CommunityDevelopment, Descriptors MdultEducation, *AnnotatedBibliographies, Broadcast Organizations (Grocps), *ReferenceMaterials, Rural Extension,State *Historical Reviews. Labor Education, Vocational Schools, Voluntary Procyon, *Teaching Methods. Units ofStudy (Subiect Fields), Universities, Agencies Identifiers -*Australia, New Guinea General works (bibliographies. yearbooks, directories,encyclopedias, periodicals), and biographical notes,international, national, and historical and descriptive surveys subject fields, state organizationsand movements, adulteducation methods and special clientele groups(women, youth, immigrants. theoretical aspects. service to education in aborigoes. armed forces,older adults, prisoners,and others), and adult the major partsofthis 868-item retrospective Papua. New Gulhea, constitute institutes, labor and bibliography on adult education inAustralia. The early mechanics' agricultural education, universityextension, communitydevelopment. workers education, among thesubject the humanities, parent education,and library adult education, are types reviewed.Educational methods includecorrespondence areas and program classes and study, group discussion,tutorial classes, residentialand nonresidential Entries are grouped undersubject headings and seminars, -

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road Map: Data Assumptions and Modelling

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road Map: Data assumptions and modelling CSIRO Paul Graham, Luke Reedman, Luis Rodriguez, John Raison, Andrew Braid, Victoria Haritos, Thomas Brinsmead, Jenny Hayward, Joely Taylor and Deb O’Connell Centre of Policy Studies Phillip Adams May 2011 Enquiries should be addressed to: Paul Graham Energy Modelling Stream Leader CSIRO Energy Transformed Flagship PO Box 330 Newcastle NSW 2300 Ph: (02) 4960 6061 Fax: (02) 4960 6054 Email: [email protected] Copyright and Disclaimer © 2011 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important Disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. CONTENTS Contents ..................................................................................................................... -

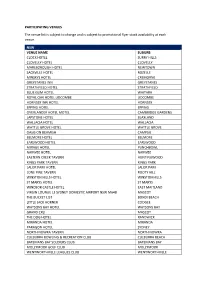

PARTICIPATING VENUES the Venue List Is Subject to Change and Is

PARTICIPATING VENUES The venue list is subject to change and is subject to promotional flyer stock availability at each venue. NSW VENUE NAME SUBURB CLOCK HOTEL SURRY HILLS CLOVELLY HOTEL CLOVELLY MARLBOROUGH HOTEL NEWTOWN SACKVILLE HOTEL ROZELLE MINSKYS HOTEL CREMORNE GREYSTANES INN GREYSTANES STRATHFIELD HOTEL STRATHFIELD BLUE GUM HOTEL WAITARA ROYAL OAK HOTEL LIDCOMBE LIDCOMBE HORNSBY INN HOTEL HORNSBY EPPING HOTEL EPPING OVERLANDER HOTEL MOTEL CAMBRIDGE GARDENS LAPSTONE HOTEL BLAXLAND WALLACIA HOTEL WALLACIA WATTLE GROVE HOTEL WATTLE GROVE OASIS ON BEAMISH CAMPSIE BELMORE HOTEL BELMORE EARLWOOD HOTEL EARLWOOD MIRAGE HOTEL PUNCHBOWL NARWEE HOTEL NARWEE EASTERN CREEK TAVERN HUNTINGWOOD KINGS PARK TAVERN KINGS PARK LALOR PARK HOTEL LALOR PARK LONE PINE TAVERN ROOTY HILL WINSTON HILLS HOTEL WINSTON HILLS ST MARYS HOTEL ST MARYS WINDSOR CASTLE HOTEL EAST MAITLAND VIRGIN LOUNGE L3 SYDNEY DOMESTIC AIRPORT NSW M648 MASCOT THE BUCKET LIST BONDI BEACH LITTLE JACK HORNER COOGEE WATSONS BAY HOTEL WATSONS BAY GRAND CRU MASCOT THE DOG HOTEL RANDWICK MIRANDA HOTEL MIRANDA PARAGON HOTEL SYDNEY NORTH NOWRA TAVERN NORTH NOWRA CULBURRA BOWLING & RECREATION CLUB CULBURRA BEACH BATEMANS BAY SOLDIERS CLUB BATEMANS BAY MOLLYMOOK GOLF CLUB MOLLYMOOK WENTWORTHVILLE LEAGUES CLUB WENTWORTHVILLE BLACKTOWN WORKERS CLUB BLACKTOWN ROOTY HILL RSL CLUB ROOTY HILL ST MARYS RUGBY LEAGUE CLUB ST MARYS ST JOHNS PARK BOWLING CLUB LTD ST JOHNS PARK CASTLE HILL RSL CLUB CASTLE HILL MORUYA BOWLING & REC CLUB LTD MORUYA COBARGO HOTEL COBARGO CRONULLA RSL MEMORIAL CLUB CRONULLA -

Presentation

10/5/2018 “Blow Up the Pokies:” Problem Electronic Gaming Machine (EGM) Gambling in Older Adults Dr Adam Searby RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia Disclosure: I have received an educational grant from Indivior to attend this year’s IntNSA educational conference. Outline • What are pokies? • Why are we blowing them up? • The scope of the problem in Australia • Older people and pokies • Future directions 1 10/5/2018 What are“pokies?” • Colloquial Australian term for a “poker machine” = “pokie” • Let’s go and play the pokies • Why are all of these places full of pokies? • Just won $100 on the pokies • Internationally known as: • Video poker machine • Fruit machine • Slot machine • Electronic gaming machine • One arm bandit Source: The Source: Advertiser Source: adelaiderememberwhen.com 2 10/5/2018 Source: thewest.com.au 3 10/5/2018 Why blow up the pokies? • In 1999, Australian band The Whitlams released the single Blow Up The Pokies • The song was inspired by two band members, Andy Lewis and Steve Plunder, who both engaged in problematic EGM gambling and lead singer, Dan Freedman’s observation that pokies were replacing live music venues in Sydney • A year after the song was released, Andy Lewis committed suicide – after losing his weekly income on the pokies and then returning to his workplace to hang himself 4 10/5/2018 In Victoria [return to player] is a minimum of 87 per cent. This doesn’t mean that every time you play you will get 87 per cent of your money back. It means that if you could play enough spins to cover every possible combination on a machine (about 80 million) then you could expect to get 87 per cent of your money back. -

Concert and Music Performances Ps48

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection CONCERT AND MUSIC PERFORMANCES PS48 This collection of posters is available to view at the State Library of Western Australia. To view items in this list, contact the State Library of Western Australia Search the State Library of Western Australia’s catalogue Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1975 April - September 1975 PS48/1975/1 Perth Concert Hall ABC 1975 Youth Concerts Various Reverse: artists 91 x 30 cm appearing and programme 1979 7 - 8 September 1979 PS48/1979/1 Perth Concert Hall NHK Symphony Orchestra The Symphony Orchestra of Presented by The 78 x 56 cm the Japan Broadcasting Japan Foundation and Corporation the Western Australia150th Anniversary Board in association with the Consulate-General of Japan, NHK and Hoso- Bunka Foundation. 1981 16 October 1981 PS48/1981/1 Octagon Theatre Best of Polish variety (in Paulos Raptis, Irena Santor, Three hours of 79 x 59 cm Polish) Karol Nicze, Tadeusz Ross. beautiful songs, music and humour 1989 31 December 1989 PS48/1989/1 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Elisa Wilson Embleton (soprano), John Kessey (tenor) Date PS number Venue Title Performers Series or notes Size D 1990 7, 20 April 1990 PS48/1990/1 Art Gallery and Fly Artists in Sound “from the Ros Bandt & Sasha EVOS New Music By Night greenhouse” Bodganowitsch series 31 December 1990 PS48/1990/2 Perth Concert Hall Vienna Pops Concert Perth Pops Orchestra, Musical director John Vienna Singers. Emma Embleton Lyons & Lisa Brown (soprano), Anson Austin (tenor), Earl Reeve (compere) 2 November 1990 PS48/1990/3 Aquinas College Sounds of peace Nawang Khechog (Tibetan Tour of the 14th Dalai 42 x 30 cm Chapel bamboo flute & didjeridoo Lama player). -

February 2017

城市漫步上海 英文版 2 月份 国内统一刊号: CN 11-5233/GO China Intercontinental Press FEBRUARY 2017 that’s Shanghai 《城市漫步》上海版 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 中国北京 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 邮编 100045 Published by China Intercontinental Press Address: 11th Floor South Building, HengHua linternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing 100045, PRC http://www.cicc.org.cn 总编辑 Editor in Chief of China Intercontinental Press: 慈爱民 Ci Aimin 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 主编 Executive Editor: 袁保安 Yuan Baoan 编辑 Editor: 王妍霖 Wang Yanlin 发行 / 市场 Circulation/Marketing: 黄静 Huang Jing, 李若琳 Li Ruolin 广告 Advertising: 林煜宸 Lin Yuchen Chief Editor Dominic Ngai Section Editors Andrew Chin, Betty Richardson, Alyssa Wieting Senior Editor Tongfei Zhang Events Editor Zoey Zha Production Manager Ivy Zhang Designer Joan Dai, Aries Ji Contributors Mario Grey, Mia Li, Ian Walker, Timothy Parent, Logan Brouse, Tristin Zhang, Sky Thomas Gidge, Amy Fabris-Shi, Catherine Lee, Jonty Dixon, Dr Daniel Meng Copy Editor Frances Arnold HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 021-8023 2199 传真 : 021-8023 2190 Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市越秀区麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Room 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Yuexiu District, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125, 传真 : 020-8357 3859-800 Shenzhen 广告代理 : -

1^ Date Rape Survivor Speaks at Colby

1^ Date ra pe survivor speaks at Colby get up to throw away his trash, she BY BROOKE subtly maneuvered over to the FITZSIMMONS same garbage barrel. They struck Staff Writer up a conversation, and things went from there. They studied together, On November 17, Colby stu- they spent time getting to know dents, faculty and administration one another, and after two weeks had the opportunity to attend "He they were not exactly dating, but Said, She Said," a lecture and dis- they were both very interested. cussion on date rape presented by One night Peter planned to take national speakers Katie Koestner her on a "real date" to a restaurant and Brett Sokolow. Koestner, who in Williamsburg. He wore a three- spoke on campus last year, was piece suit, she wore her tenth grade excited by the large student turn- homecoming dress. At the restau- out, especially from male students rant he ordered champagne, and although Koestner did not drink at at Colby. She commented that last Echo photo hy Melame Guryansky year she thought she "was at a the time, he persuaded her to have women's college and some of the Katie Koestner visits Colby. just one glass. He off ered to take women had brought their boy- something that happened in dark her to his house in Greece for the friends along." In the case of sexual alleys, the attacker was a stranger, summer under the condition that assault, both men and womenalike and the notion that a rapist could she would have sex when he should be aware of the risks, re- be a friend was not even consid- wanted to. -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

The Lemonheads Kommer Til Pumpehuset Med Nyt Album I Bagagen

2018-12-04 15:30 CET The Lemonheads kommer til Pumpehuset med nyt album i bagagen. THE LEMONHEADS 4. MARTS 2019 PUMPEHUSET The Lemonheads’ frontmand, Evan Dando, har en besynderlig evne til at gøre et nummer til sit eget. Han vil kunne få en takeaway-ordre over telefonen til at lyde som en hjerteskærende sang der ville passe ind på enhver bar. Hans følsomme, modne, vokal har gjort ham til en af de store udtryksfulde sangere. The Lemonheads hylder helte som Nick Cave, The Bevis Frond, Yo La Tengo, Lucinda Williams og Paul Westerberg, når de fremfører deres unikke covernumre. Det er næsten 10 år siden The Lemonheads pludselig satte tingene på hold, efter udgivelsen af deres niende album ’Varshons’, der var livlig samling covernumre som fik en meget flot modtagelse. Evan Dandos, evne til at ”twang” med sin vokal fik covernumrene på ’Varshons’ til at lyde som en gammel jukebox og denne formel bliver ført videre på bandets kommende album, ’Varshons II’. Med en udgivelsesdato sat til 8. februar, kommer grunge- pop-heltene til Pumpehuset med en ny samling covernumre og viser hvordan man gør et nummer til sit eget, når de giver deres take på sange som The Eagles’ ’Take It Easy’, Lucinda Wiliams’ ’Abandoned’ m. fl. Billetpriser: 225 kr. + gebyr Billetsalget er starter fredag 7. december via livenation.dk og ticketmaster.dk. Live Nation er verdens førende producent og formidler af live entertainment oplevelser. På verdensplan bliver det til + 25.000 årlige koncerter og mere end 68 millioner solgte billetter. Live Nation Denmark er Danmarks førende koncertbureau med 40 engagerede medarbejdere der holder til på Frederiksberg Allé i København. -

Pubtic A4 Mag January 2015.Indd

Volume 1 No.1 – JANUARY 2015 2014 In Review Justin Hemmes exclusive on pubs and the future Real Estate Rising – where’s the boom headed? Quick, easy money-maker cocktails January 2015 PubTIC | 1 Contents JANUARY 2015 6 14 12 FEATURES COLUMNS REGULARS 6. 2014-The Year That Was 24. Where’s the Money? 4. Editor’s rant Taking a big-picture look at the Manager of Perth’s Luxe Bar and 10. Brand News: product news for major pub events of the last year. former liquor mag editor Sacha pubs. Delfosse talks pub summer 14. View To The Future cocktails. 12. The Flutter: news and trends Hospitality legends Justin from the world of gaming. Hemmes and Andy Freeman speak exclusively to PubTIC about ideas, industry and innovation. 20. Pub Values An in-depth look at influences on pub real estate in the current market. January 2015 PubTIC | 3 Editor’s Rant I was born in a pub. By that, I don’t mean that is the ‘pub’ represents more in our hostile, metaphorically I have spent too much time sprawling environment than any other country haunting public houses. After entering the world in I have encountered. Typically the centre of Mona Vale hospital, my parents brought me home towns, frequently the shelter in crisis or the hub to the Frenchs Forest Hotel, where they worked as of community change, from tin shacks to multi- recovery managers for Tooths. One of my earliest million dollar creations, the pub is one of the most memories is sitting outside in the courtyard, aged 3, ubiquitous and socially significant industries in watching the enormous drive-in movie screen next Australia.