Interrogating the Shaping of Sexual Identities Through the Digital Fan Spaces of the Eurovision Song Contest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Russia and Ukraine's Use of the Eurovision Song

Lund University FKVK02 Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Peace and Conflict Studies Supervisor: Fredrika Larsson The Battle of Eurovision A case study of Russia and Ukraine’s use of the Eurovision Song Contest as a cultural battlefield Character count: 59 832 Julia Orinius Welander Abstract This study aims to explore and analyze how Eurovision Song Contest functioned as an alternative – cultural – battlefield in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict over Crimea. With the use of soft power politics in warfare as the root of interest, this study uses the theories of cultural diplomacy and visual international relations to explore how images may be central to modern-day warfare and conflicts as the perception of. The study has a theory-building approach and aims to build on the concept of cultural diplomacy in order to explain how the images sent out by states can be politized and used to conduct cultural warfare. To explore how Russia and Ukraine used Eurovision Song Contest as a cultural battlefield this study uses the methodological framework of a qualitative case study with the empirical data being Ukraine’s and Russia’s Eurovision Song Contest performances in 2016 and 2017, respectively, which was analyzed using Roland Barthes’ method of image analysis. The main finding of the study was that both Russia and Ukraine used ESC as a cultural battlefield on which they used their performances to alter the perception of themselves and the other by instrumentalizing culture for political gain. Keywords: cultural diplomacy, visual IR, Eurovision Song Contest, Crimea Word count: 9 732 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ -

Copenhagen – Stockholm – Oslo in 5 Days

Train trips in Scandinavia Enjoy the Scandinavian capitals COPENHAGEN – STOCKHOLM Sweden – OSLO IN 5 DAYS Five days, three remarkable cities, one diverse and amazing Norway experience. Visiting the capitals of Denmark, Sweden and Norway all in one trip offers an enormous wealth of design and architecture, world-class cuisine, fashion, royalty and fascinating historical features. Just do it. Denmark Day 1 to 2: Copenhagen – The City of Design Come and meet a jovial and convivial city full of alleyways lined with charming old houses. That said, Copenhagen is also a modern city where design is obvious in all its forms and featuring lively cafés and high-quality restaurants. Take a stroll down the famous pedestrianised street of Strøget and enjoy everything from high-end shopping to lively street artists and musicians. Or why not hire a bike and explore 5 h the city in true Danish style? Sights well worth seeing include the traditional Tivoli amusement park and the world-famous and popular “Little Mermaid” statue. And don’t forget to sample the very essence of all things Danish: the open Danish sandwich, or “smørrebrød” as it is known to the locals. Day 2 to 3: Stockholm – The Capital of Scandinavia Stockholm is one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Built on fourteen islands and directly connected to an archipelago, it’s a city of contrasts and is often considered unique by visitors. It’s an international metropolis, modern and trendy, yet bursting with culture, traditions and a history that stretches back an entire millennium. With 19 roof-top bars in the city centre and more than a hundred White Guide restaurants, 5 h few cities can compete with Stockholm’s ability to offer a taste of modern urban life, history and wonderful countryside – all in the same day. -

Burden Sharing and Dublin Rules – Challenges of Relocation of Asylum Seekers

Athens Journal of Law - Volume 3, Issue 1 – Pages 7-20 Burden Sharing and Dublin Rules – Challenges of Relocation of Asylum Seekers By Lehte Roots Mediterranean route has become the most used irregular migration route to access the borders of European Union. Dublin regulation has set up principles that a country which has allowed the immigrant to access its territory either by giving a visa or giving an opportunity to cross the border is responsible for asylum application and the processing procedure of this application. These rules have put an enormous pressure to the EU countries that are at the Mediterranean basin to deal with hundreds of thousands of immigrants. At the same time EU is developing its migration legislation and practice by changing the current directives. The role of the Court of Justice in this development should also not be under diminished. From one point of view EU is a union where principles of solidarity and burden sharing should be the primary concern, the practice though shows that the initiatives of relocation of asylum seekers and refugees is not taken by some EU member states as a possibility to contribute to these principles, but as a threat to their sovereignty. This paper is discussing the further opportunities and chances to develop the EU migration law and practice in order to facilitate the reception of persons arriving to EU borders by burden sharing. Keywords: Irregular migration, relocation, resettlement, Dublin rules, burden sharing Introduction “We all recognized that there are no easy solutions and that we can only manage this challenge by working together, in a spirit of solidarity and responsibility. -

90 Av 100 Ålänningar Sågar Upphöjd Korsning Säger Nej

Steker crépe på Lilla holmen NYHETER. Fransmannen Zed Ziani har fl yttat sitt créperie till Lilla holmen i Mariehamn och för första gången på många år fi nns det servering igen på friluftsområdet. Både salta och söta crépe, baguetter och kaffe fi nns på menyn i det lilla caféet med utsikt över fågeldammen Lördag€ SIDAN 18 12 MAJ 2007 NR 100 PRIS 1,20 och Slemmern. 90 av 100 ålänningar sågar upphöjd korsning Säger nej. Annette Gammals deltog i Nyans gatupejling om Ålandsvägens upphöjda korsning- ar. Men planerarna har politikernas uppdrag att se Men frågan är: Vems bekvämlighet är viktigast? till också den lätta trafi kens intressen. NYHETER. Ska alla trafi kanter – bilister, – Jag tycker mig känna igen trafi kplane- ålänningarna kanske har svårare än andra att – Jag hatar bumpers, sa Ingmar Håkansson cyklister, fotgängare och gamla med rullator ringsdiskussionen från 1960-talet när devisen ge avkall på bilbekvämligheten. från Lumparland som har jobbat 26 år som – behandlas jämlikt i stadstrafi ken? var att bilarna ska fram, allt ska ske på bilis- – Åland är väldigt bilberoende. Men man yrkeschaufför. Ja, säger planerarna i Mariehamn. Politi- ternas villkor och de oskyddade och sårbara måste ändå tänka på att också andra har rätt 90 personer svarade nej på frågan om de vill kerna har godkänt de styrdokument som de trafi kanterna får klara sig bäst de kan, säger till en säker trafi kmiljö. ha upphöjda korsningar, tio svarade ja. baserar ombyggnaden av Ålandsvägen på. tekniska nämndens ordförande Folke Sjö- Känslorna var starka då Nyan i går pejlade – Jag har barn som skall gå över Ålandsvä- Det som nu har hänt är att en del politiker lund. -

Irīna Ivaškina

IRĪNA IVAŠKINA Title: Ms. Citizenship: Latvia Mobile Phone: (+371) 28252237 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Riga Stradins University Riga, Latvia September 2008 – Master’s Degree of Social Science in Politics, Academic study program: International Relations Riga Stradins University Riga, Latvia September 2003 - June 2007 Bachelor’s Degree of Social Science in Politics, Academic study program: International Relations- European studies Academic papers: Latvian development cooperation policy towards Georgia (2005) European Neighbourhood Policy towards Georgia: opportunities and constraints (2006) Georgia’s social identity in relationship with the EU and Russia after the Rose revolution (2007) WORK EXPERINCE Latvian Transatlantic Organisation (LATO) Riga, Latvia February 2008 – present Project Manager Main responsibilities: project management; public relations; communication with international partners; office work. Main projects: Riga Conference (2008, 2009, 2010) www.rigaconference.lv Public discussion “NATO’s Future: A Baltic View” (June 1, 2010, Riga) Akhaltsikhe International Security Seminar 2008 (November 24-26, 2009, Tbilisi, Georgia) Association ‘’Georgian Youth for Europe’’ Rustavi, Georgia July 2007 – January 2008 European Volunteer Service, Volunteer Main responsibilities: Education of youngsters about the EU and NATO; Promotion of the “Youth in Action” programme among local youngsters; Assisting in implementation of projects. 1 Latvian Transatlantic organisation (LATO) Riga, Latvia September – December 2006 -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 20/12/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 20/12/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Perfect - Ed Sheeran Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer - Elmo & All I Want For Christmas Is You - Mariah Carey Summer Nights - Grease Crazy - Patsy Cline Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Feliz Navidad - José Feliciano Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas - Michael Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Killing me Softly - The Fugees Don't Stop Believing - Journey Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Zombie - The Cranberries Baby, It's Cold Outside - Dean Martin Dancing Queen - ABBA Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree - Brenda Lee Girl Crush - Little Big Town Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi White Christmas - Bing Crosby Piano Man - Billy Joel Jackson - Johnny Cash Jingle Bell Rock - Bobby Helms Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Baby It's Cold Outside - Idina Menzel Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Let It Go - Idina Menzel I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Last Christmas - Wham! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! - Dean Martin You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch - Thurl Ravenscroft Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Africa - Toto Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer - Alan Jackson Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor The Christmas Song - Nat King Cole Wannabe - Spice Girls It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas - Dean Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Please Come Home For Christmas - The Eagles Wagon Wheel - -

WEE19 – Reviewed by London Student

West End Eurovision 2019: A Reminder of the Talent and Supportive Community in the Theatre Industry ARTS, THEATRE Who doesn’t love Eurovision? The complete lack of expectation for any UK contestant adds a laissez faire tone to the event that works indescribably well with the zaniness of individual performances. Want dancing old ladies? Look up Russia’s 2012 entrance. Has the chicken dance from primary school never quite left your consciousness? Israel in 2018 had you covered. Eurovision is camp and fun, and we need more of that these days… cue West End Eurovision, a charity event where the casts from different shows compete with previous Eurovision songs to win the approval of a group of judges and the audience. The seven shows competing were: Only Fools and Horses, Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, Aladdin, Mamma Mia!, Follies, The Phantom of the Opera, and Wicked. Each cast performed for four judges – Amber Davies, Bonnie Langford, Wayne Sleep, and Tim Vincent – following a short ident. Quite what these were for I’m not sure was explained properly to the cast: are they adverts for their shows (Everybody’s Talking About Jamie), adverts for the song they’re to perform (Phantom) or adverts for Eurovision generally (Mamma Mia!)? I don’t know, but they were all amusing and a good way to introduce each act. The cast of Only Fools and Horses opened the show, though they unfortunately came last in the competition, a less-than jubly result. That said, with sparkling costumes designed by Lisa Bridge, the performance of ‘Dancing Lasha Tumbai’, first performed by Ukraine in 2007, was certainly in the spirit of Eurovision and made for a sound opening number. -

Voyager of the Seas® - 2022 Europe Adventures

Voyager of the Seas® - 2022 Europe Adventures Get your clients ready to dive deep into Europe in Summer 2022. They can explore iconic destinations onboard the new Odyssey of the Seas S M. Fall in love with the Med's greatest hits and discover its hidden gems onboard Voyager of the Seas® ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 9-Night Best of Western April 15, 2022 Barcelona, Spain • Cartagena, Spain • Gibraltar, Europe United Kingdom • Cruising • Lisbon, Portugal • Cruising (2 nights) • Amsterdam, Netherlands Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Best of Northern April 24, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Oslo, Norway Europe August 28, 2022 (Overnight) • Kristiansand, Norway • Cruising • Skagen, Denmark • Gothenburg, Sweden • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Scandinavia & May 1, 8, 15, 22, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Russia Sweden • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia • Helsinki, Finland • Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Scandinavia & May 29, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Russia Sweden • Helsinki, Finland • St. Petersburg, Russia • Tallinn, Estonia • Copenhagen, Denmark 10-Night Scandinavia & June 5, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Cruising • Stockholm, Russia Sweden • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia (Overnight) • Helsinki, Finland • Riga, Latvia • Visby, Sweden • Cruising • Copenhagen, Denmark Book your Europe adventures today! Features vary by ship. All itineraries are subject to change without notice. ©2020 Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd. Ships’ registry: The Bahamas. 20074963 • 11/24/2020 ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 11-Night Scandinavia & June 15, 2022 Copenhagen, Denmark • Ronne, Bornholm, Russia Denmark • Cruising • Tallinn, Estonia • St. Petersburg, Russia (Overnight) • Helsinki, Finland • Visby, Sweden • Riga, Latvia • Cruising (2-Nights) • Copenhagen, Denmark 7-Night Scandinavia & July 3, 2022 Stockholm, Sweden• Cruising • St. -

Tartu Arena Tasuvusanalüüs

Tartu Arena tasuvusanalüüs Tellija: Tartu Linnavalitsuse Linnavarade osakond Koostaja: HeiVäl OÜ Tartu 2016 Copyright HeiVäl Consulting 2016 1 © HeiVäl Consulting Tartu Arena tasuvusanalüüs Uuring: Tartu linna planeeritava Arena linnahalli tasuvusanalüüs Uuringu autorid: Kaido Väljaots Geete Vabamäe Maiu Muru Uuringu teostaja: HeiVäl OÜ / HeiVäl Consulting ™ Kollane 8/10-7, 10147 Tallinn Lai 30, 51005 Tartu www.heival.ee [email protected] +372 627 6190 Uuringu tellija: Tartu Linnavalitsus, Linnavarade osakond Uuringuprojekt koostati perioodil aprill – juuli 2016. 2 © HeiVäl Consulting Tartu Arena tasuvusanalüüs Sisukord Kokkuvõte .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1 Uuringu valim .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Tartu linn .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Euroopa .......................................................................................................................................... 11 2 Spordi- ja kultuuriürituste turuanalüüs ........................................................................................... 13 2.1 Konverentsiürituste ja messide turuanalüüs Tartus ....................................................................... 13 2.2 Kultuuriürituste turuanalüüs Tartus ............................................................................................... -

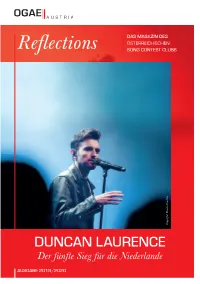

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Media Release Thursday 23 January 2020

Media Release Thursday 23 January 2020 Eurovision royalty to grace Eurovision – Australia Decides 2020 Watch the Live TV Final on Saturday 8 February 8.30pm AEDT on SBS and cast your vote SBS and production partner Blink TV today revealed Swedish pop phenomenon and winner of the Eurovision Song Contest 2015 Måns Zelmerlöw is heading to the Gold Coast to perform and be one of the Jury members for Eurovision – Australia Decides next month. Swedish singer, songwriter and TV presenter Måns Zelmerlöw masterminded one of the most memorable wins in Swedish Eurovision Song Contest history with his performance of the uplifting multi- platinum single Heroes. After winning, Heroes peaked at #1 on iTunes in 21 countries and his tour across Europe took him to 22 cities – most of them at sold out venues. In 2016, he co-hosted the song contest in Stockholm, Sweden where Dami Im made history winning the Jury vote and coming second overall with her performance of Sound of Silence. Måns Zelmerlöw said: “I’m so excited to come back to my favourite country to perform, and to be a guest judge on the National Eurovision selection show! Australia has sent great songs ever since they joined the Eurovision Song Contest and I think 2020 could be THE year. I might sing a line or two from my winning song from 2015 and from my newest single, Walk with Me, featuring the wonderful Dami Im. Can’t wait to see you all!” Joining him in Australia is Eurovision boss Jon Ola Sand who will step down as Executive Supervisor after Rotterdam 2020. -

Baku Airport Bristol Hotel, Vienna Corinthia Hotel Budapest Corinthia

Europe Baku Airport Baku Azerbaijan Bristol Hotel, Vienna Vienna Austria Corinthia Hotel Budapest Budapest Hungary Corinthia Nevskij Palace Hotel, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Fairmont Hotel Flame Towers Baku Azerbaijan Four Seasons Hotel Gresham Palace Budapest Hungary Grand Hotel Europe, St Petersburg St Petersburg Russia Grand Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton DoubleTree Zagreb Zagreb Croatia Hilton Hotel am Stadtpark, Vienna Vienna Austria Hilton Hotel Dusseldorf Dusseldorf Germany Hilton Milan Milan Italy Hotel Danieli Venice Venice Italy Hotel Palazzo Parigi Milan Italy Hotel Vier Jahreszieten Hamburg Hamburg Germany Hyatt Regency Belgrade Belgrade Serbia Hyatt Regenct Cologne Cologne Germany Hyatt Regency Mainz Mainz Germany Intercontinental Hotel Davos Davos Switzerland Kempinski Geneva Geneva Switzerland Marriott Aurora, Moscow Moscow Russia Marriott Courtyard, Pratteln Pratteln Switzerland Park Hyatt, Zurich Zurich Switzerland Radisson Royal Hotel Ukraine, Moscow Moscow Russia Sacher Hotel Vienna Vienna Austria Suvretta House Hotel, St Moritz St Moritz Switzerland Vals Kurhotel Vals Switzerland Waldorf Astoria Amsterdam Amsterdam Netherlands France Ascott Arc de Triomphe Paris France Balmoral Paris Paris France Casino de Monte Carlo Monte Carlo Monaco Dolce Fregate Saint-Cyr-sur-mer Saint-Cyr-sur-mer France Duc de Saint-Simon Paris France Four Seasons George V Paris France Fouquets Paris Hotel & Restaurants Paris France Hôtel de Paris Monaco Monaco Hôtel du Palais Biarritz France Hôtel Hermitage Monaco Monaco Monaco Hôtel