Holocaust Memory for the Millennium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theresienstadt Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Theresienstadt concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E "Theresienstadt" redirects here. For the town, see Terezín. Navigation Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt Ghetto,[1][2] Main page [3] was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress and garrison city of Contents Terezín (German name Theresienstadt), located in what is now the Czech Republic. Featured content During World War II it served as a Nazi concentration camp staffed by German Nazi Current events guards. Random article Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from Donate to Wikipedia malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail Interaction transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied [4] Help Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. About Wikipedia Contents Community portal Recent changes 1 History The Small Fortress (2005) Contact Wikipedia 2 Main fortress 3 Command and control authority 4 Internal organization Toolbox 5 Industrial labor What links here 6 Western European Jews arrive at camp Related changes 7 Improvements made by inmates Upload file 8 Unequal treatment of prisoners Special pages 9 Final months at the camp in 1945 Permanent link 10 Postwar Location of the concentration camp in 11 Cultural activities and -

STATEMENT by MR. ANDREY KELIN, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE of the RUSSIAN FEDERATION, at the 1045Th MEETING of the OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL

PC.DEL/393/15/Rev.1 25 March 2015 ENGLISH Original: RUSSIAN Delegation of the Russian Federation STATEMENT BY MR. ANDREY KELIN, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION, AT THE 1045th MEETING OF THE OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL 19 March 2015 On the growth of racism, radicalism and neo-Nazism in the OSCE area Mr. Chairperson, The growth in manifestations of racism, violent extremism, aggressive nationalism and neo-Nazism remain, as ever, one of the most serious threats in the OSCE area. Unfortunately, the work in the OSCE to combat the spread of radical and neo-Nazi views within society is not being done systematically. Despite commitments in this area, there is no single OSCE action plan as there is for combating trafficking in human beings, improving the situation of Roma and Sinti or promoting gender equality. Every OSCE country has its problems connected with the growth of radicalism and nationalistic extremism. Russia is not immune to these abhorrent phenomena either. The approaches to resolving these problems in the OSCE participating States vary though. In our country, there is a package of comprehensive measures in place, ranging from criminal to practical, to nip these threats in the bud. Neo-Nazis and anyone else who incites racial hatred are either in prison or will end up there sooner or later. However, in many countries, including those that are proud to count themselves among the established democracies, people close their eyes to such phenomena or justify these activities with reference to freedom of speech, assembly and association. We are surprised at the position taken by the European Union, which attempts to find justification for neo-Nazi demonstrations and gatherings sometimes through particular historical circumstances and grievances and sometimes under the banner of democracy. -

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

© Copyright by Ann Littmann Rappoport 1978 SOVIET POLICIES TOWARD ITS UNION REPUBLICS: A

790820A RAPPOPORT t ANN LITTMANN SOVIET POLICIES TDWARD ITS JNION REPUBLICS A COMPOSITIONAL ANALYSIS OF "NATIONAL INTEGRATION". THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY, PH.D., 1978 University, Microfilm s International .TOO N / I I U HOAD. ANN AHIJOH. Ml 4H1<K> © Copyright by Ann Littmann Rappoport 1978 SOVIET POLICIES TOWARD ITS UNION REPUBLICS: A COMPOSITIONAL ANALYSIS OF "NATIONAL INTEGRATION" DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ann Littmann Rappoport ***** The Ohio State University 1978 Reading Committee: Approved By Philip D. Stewart, Ph.D. R. William Liddle, Ph.D. Loren K. Waldman, Ph.D. M) Adviser \ Department of Political Science Dedicated to the most special Family with all my love. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A lengthy appendix might be in order to adequately acknowledge those persons who provided valuable assistance to this dissertation. Many of their names do indeed appear throughout the footnotes and bibliography of this study. Certain others are acknowledged for the inspira tion they provided me through their dedicated teaching. My sincere appreciation goes to my thesis and Major Adviser, Prof. Philip D. Stewart, who supported and somehow tactfully guided this undertaking. I also thank Prof. R. William Liddle and Prof. Loren K. Waldman, for their incisive comments, especially at the time of this study's "debut" presentation. Professor Waldman1s suggestion to investigate the Lieberson Diversity Measure as a means for approaching my compositional problem, made a great independent contribution toward this study while also serving to provide my Entropy Index with additional credibility. In preparing and typing this manuscript, the work of Mrs. -

China's False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United

W O R K I N G P A P E R # 7 8 China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War By Milton Leitenberg, March 2016 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Drew Hayden Taylor, Native Canadian Playwright in His Times

BRIDGING THE GAP: DREW HAYDEN TAYLOR, NATIVE CANADIAN PLAYWRIGHT IN HIS TIMES Dale J. Young A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2005 Committee: Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor Dr. Lynda Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Jonathan Chambers Bradford Clark © 2005 Dale Joseph Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor In his relatively short career, Drew Hayden Taylor has amassed a significant level of popular and critical success, becoming the most widely produced Native playwright in the world. Despite nearly twenty years of successful works for the theatre, little extended academic discussion has emerged to contextualize Taylor’s work and career. This dissertation addresses this gap by focusing on Drew Hayden Taylor as a writer whose theatrical work strives to bridge the distance between Natives and Non-Natives. Taylor does so in part by humorously demystifying the perceptions of Native people. Taylor’s approaches to humor and demystification reflect his own approaches to cultural identity and his expressions of that identity. Initially this dissertation will focus briefly upon historical elements which served to silence Native peoples while initiating and enforcing the gap of misunderstanding between Natives and non-Natives. Following this discussion, this dissertation examines significant moments which have shaped the re-emergence of the Native voice and encouraged the formation of the Contemporary Native Theatre in Canada. Finally, this dissertation will analyze Taylor’s methodology of humorous demystification of Native peoples and stories on the stage. -

Opening Statements

Opening Statements Opening Ceremony Remarks at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Mr. Miles Lerman CHAIRMAN, UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL COUNCIL UNITED STATES It is proper and most fitting that this conference began with a symbolic ceremony of silent contemplation in the Hall of Remembrance of the Holocaust Memorial Museum where we invoked memory and paid tribute to those who were consumed in the Nazi inferno. Now let me welcome you to the Washington Conference on Holocaust-Era Assets. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is pleased to co-chair with the State Department this historic event. For the next three days representatives of 44 countries will have the opportunity to explore a just and orderly return of confiscated assets to their rightful owners. It took over 50 years for the world to come to grips with the fact that the biggest murder of the century; it was also, as my friend Ben Meed reminds us, the biggest robbery in history. This fact is not limited to one country only. What really shocked the conscience of the world was the discovery that even after the war, some countries tried to gain materially from this cataclysm by refusing to return to the rightful owners what was justly theirs. The refusal to respond to these rightful claims was a great injustice, a moral wrong which can not be ignored. And this is what brings us together today. We are here to make sure that these wrongs are corrected in a just and proper manner. 4 WASHINGTON CONFERENCE ON HOLOCAUST-ERA ASSETS Under Secretary Eizenstat and Edgar Bronfman deserve our gratitude for their unrelenting efforts to bring about full accountability for all wrongs that must be made right. -

Parallel Journeys:Parallel Teacher’S Guide

Teacher’s Parallel Journeys: The Holocaust through the Eyes of Teens Guide GRADES 9 -12 Phone: 470 . 578 . 2083 historymuseum.kennesaw.edu Parallel Journeys: The Holocaust through the Eyes of Teens Teacher’s Guide Teacher’s Table of Contents About this Teacher’s Guide.............................................................................................................. 3 Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Georgia Standards of Excellence Correlated with These Activities ...................................... 5 Guidelines for Teaching about the Holocaust .......................................................................... 12 CORE LESSON Understanding the Holocaust: “Tightening the Noose” – All Grades | 5th – 12th ............................ 15 5th Grade Activities 1. Individual Experiences of the Holocaust .......................................................................... 18 2. Propaganda and Dr. Seuss .................................................................................................. 20 3. Spiritual Resistance and the Butterfly Project .................................................................. 22 4. Responding to the St. Louis ............................................................................................... 24 5. Mapping the War and the Holocaust ................................................................................. 25 6th, 7th, and 8th Grade Activities -

Estudio De La Evolución De Un Fitopatógeno: Genómica Comparada Del Hongo Patógeno De Maíz Colletotrichum Graminicola

Universidad de salamanca FACULTAD DE BIOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE MICROBIOLOGÍA Y GENÉTICA ÁREA: GENÉTICA TESIS DOCTORAL Estudio de la evolución de un fitopatógeno: Genómica comparada del hongo patógeno de maíz Colletotrichum graminicola GABRIEL EDUARDO RECH SALAMANCA, 2013 UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA Facultad de Biología Departamento de Microbiología y Genética Área: Genética Centro Hispano-Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias Insight into the evolution of a plant pathogen: Comparative genomic analysis of the fungal maize pathogen Colletotrichum graminicola PhD Thesis Programa de Doctorado: Agrobiotecnología Órgano responsable del Programa de Doctorado: Departamento de Fisiología Vegetal Gabriel Eduardo Rech Salamanca, 2013 UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA Facultad de Biología Departamento de Microbiología y Genética Área: Genética Centro Hispano-Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias Estudio de la evolución de un fitopatógeno: Genómica comparada del hongo patógeno de maíz Colletotrichum graminicola Tesis Doctoral Programa de Doctorado: Agrobiotecnología Órgano responsable del Programa de Doctorado: Departamento de Fisiología Vegetal Gabriel Eduardo Rech Salamanca, 2013 D. Luis Román Fernández Lago, Director del Departamento de Microbiología y Genética de la Facultad de Biología de la Universidad de Salamanca y Dña. Berta Dopico Rivela, Directora del Departamento de Fisiología Vegetal de la Facultad de Biología de la Universidad de Salamanca, órgano responsable del Programa de Doctorado en Agrobiotecnología CERTIFICAMOS: Que la presente Memoria titulada “Estudio de la evolución de un fitopatógeno: Genómica comparada del hongo patógeno de maíz Colletotrichum graminicola”, ha sido realizada en el Departamento de Microbiología y Genética de la Facultad de Biología y el Centro Hispano-Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias de la Universidad de Salamanca por el Licenciado D. Gabriel Eduardo Rech, bajo la dirección del Dr. -

Harvard Historical Studies • 173

HARVARD HISTORICAL STUDIES • 173 Published under the auspices of the Department of History from the income of the Paul Revere Frothingham Bequest Robert Louis Stroock Fund Henry Warren Torrey Fund Brought to you by | provisional account Unauthenticated Download Date | 4/11/15 12:32 PM Brought to you by | provisional account Unauthenticated Download Date | 4/11/15 12:32 PM WILLIAM JAY RISCH The Ukrainian West Culture and the Fate of Empire in Soviet Lviv HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2011 Brought to you by | provisional account Unauthenticated Download Date | 4/11/15 12:32 PM Copyright © 2011 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Risch, William Jay. The Ukrainian West : culture and the fate of empire in Soviet Lviv / William Jay Risch. p. cm.—(Harvard historical studies ; 173) Includes bibliographical references and index. I S B N 9 7 8 - 0 - 6 7 4 - 0 5 0 0 1 - 3 ( a l k . p a p e r ) 1 . L ’ v i v ( U k r a i n e ) — H i s t o r y — 2 0 t h c e n t u r y . 2 . L ’ v i v ( U k r a i n e ) — P o l i t i c s a n d government— 20th century. 3. L’viv (Ukraine)— Social conditions— 20th century 4. Nationalism— Ukraine—L’viv—History—20th century. 5. Ethnicity— Ukraine—L’viv— History—20th century. -

TRANSLATED and EDITED by GEORGE S.N. LUCKYJ Harvard Series in Ukrainian Studies Diasporiana.Org.Ua Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute Mono~Raph Series

TRANSLATED AND EDITED BY GEORGE S.N. LUCKYJ Harvard Series in Ukrainian Studies diasporiana.org.ua Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute Mono~raph Series Editarial Board Omeljan Pritsak, Editar-in-Chief Ihor Sev~enko Paul R. Magocsi, Managing Editar Committee on Ukrainian Studies Edward Keenan Horace G. Lunt Richard E. Pipes Omeljan Pritsak, Chairman Ihor Sevl:enko Wiktor Weintraub Cambridge, Massachusetts Ievhen Sverstiuk Clandestine Essays Translation and an Introduction by George S. N. Luckyj Published by the Ukrainian Academic Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute 1976 The Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute was established in 1973 as an integral part of Harvard University. It supports research associates and visiting scholars who are engaged in projects concerned with all aspects of Ukrainian studies. The Institute also works in close cooperation with the Committee on Ukrainian Studies, which supervises and coordinates the teaching of Ukrain ian history, language, and literature at Harvard University. Copyright© 1976 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data ,......, ,.-.... Sverstiuk, IEvhen. Clandestine essays. (Monograph series - Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute) Includes bibliographical references. CONTENTS: A cathedral in scaffolding. -Ivan Kot liarevs'kyi is laughing. -Final plea before the court. 1. Ukraine-Politics and govemment-1917- -Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Dissenters Ukraine-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Title. II. Series: Harvard University Research Institute. Monograph series- Harvard Ukrainian Research Insti tute. DK508.8.S825 322.4'4'094 771 76-20768 ISBN 0-87287-151-7 ISBN 0-87287-1584 pbk. Ukrainian Academic Press, a division of Libraries Unlimited, Inc., P.O. -

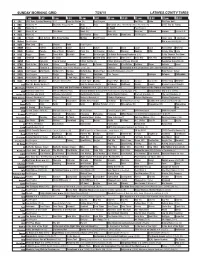

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015.