Drew Hayden Taylor, Native Canadian Playwright in His Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

The Killam Trusts Annual Report 2007

THE KILLAM TRUSTS ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Sarah Pace, BA (Hons) Administrative Officer to the Killam Trusts 1391 Seymour Street Halifax, NS B3H 3M6 T: (902) 494-1329 F:(902) 494-6562 [email protected] Published by the Trustees of the Killam Trusts www.killamtrusts.ca THE KILLAM TRUSTS ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Sarah Pace, BA (Hons) Administrative Officer to the Killam Trusts 1391 Seymour Street Halifax, NS B3H 3M6 T: (902) 494-1329 F:(902) 494-6562 [email protected] Published by the Trustees of the Killam Trusts www.killamtrusts.ca 2007 Annual Report of The Killam Trustees 2007 Annual Report of The Killam Trustees With infinite sadness, we record that our beloved fellow Trustee, W. Robert Wyman, passed away in June. A few weeks before his death, Dr. Indira Samarasekera, President and Vice Chancellor of the University of Alberta and Dr. Mark Dale, Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, journeyed to Vancouver to con- fer an honourary LLD degree on Bob at his home. At the U of A Special Convocation held in Edmonton later in the year, Bob’s wife Donna and daughter Robin told us of his deep satisfaction at having received this honour from the university of his birthplace and childhood, the city of Edmonton. Please see page 17 for a more detailed tribute to this remarkable Canadian and his inestimable contribution to higher education in Canada. Moncton, New Brunswick is a medium-sized but up and coming city. Its recent growth rests on three promising features: its loca- tion at the transportation hub of the Maritime Provinces; its highly entrepreneurial citizenry; and a thriving cultural life. -

CANADA's ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET Thu, Oct 20, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2016 // 17 SEASON Northrop Presents CANADA'S ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET Thu, Oct 20, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage DRACULA Dear Northrop Dance Lovers, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents It’s great to welcome Canada’s Royal Winnipeg Ballet back to Northrop! We presented their WONDERLAND at the Orpheum in 2011, but they last appeared on this stage in 2009 with their sensational Moulin Rouge. Northrop was a CANADA'S ROYAL very different venue then, and the dancers are delighting in the transformation of this historic space. The work that Royal Winnipeg brings us tonight boasts WINNIPEG BALLET quite a history as well. When it first came out in 1897, Bram th Stoker’s novel was popular enough, but it was the early 20 Under the distinguished Patronage of His Excellency century film versions that really caused its popularity to The Right Honourable David Johnston, C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.D. skyrocket. The play DRACULA appeared in London in 1924 Governor General of Canada and had a successful three-year tour, and then the American version opened in New York City in 1927 and grossed over $2 Founders, GWENETH LLOYD & BETTY FARRALLY million in its first year (that’s in 1927 dollars, and 1927 ticket Artistic Director Emeritus, ARNOLD SPOHR, C.C., O.M. prices). Founding Director, School Professional Division, DAVID MORONI, C.M. Founding Director, School Recreational Division, JEAN MACKENZIE Christine Tschida. Photo by Tim Rummelhoff. So, what is it about this vampire tale that still evokes dread and horror, but most of all, fascination? That’s a subject Artistic Director currently being explored by our first University Honors Program-coordinated interdisciplinary, outside- ANDRÉ LEWIS the-classroom Honors Experience: Dracula in Multimedia. -

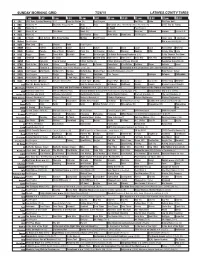

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

A Feminist-Foucauldian Approach to Sexual Violence and Survival

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 Surviving History of Sexuality: A Feminist-Foucauldian Approach to Sexual Violence and Survival Merritt Rehn-Debraal Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rehn-Debraal, Merritt, "Surviving History of Sexuality: A Feminist-Foucauldian Approach to Sexual Violence and Survival" (2015). Dissertations. 1967. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1967 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2015 Merritt Rehn-Debraal LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO SURVIVING HISTORY OF SEXUALITY: A FEMINIST-FOUCAULDIAN APPROACH TO SEXUAL VIOLENCE AND SURVIVAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN PHILOSOPHY BY MERRITT REHN-DEBRAAL CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2015 Copyright by Merritt Rehn-DeBraal, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For his breadth of knowledge, insights, and careful readings I am grateful to my dissertation director, Andrew Cutrofello. Many thanks also to my other readers: Jacqueline Scott, who has undoubtedly helped me to become a better writer and philosopher; and Hanne Jacobs, whose enthusiasm renews my excitement in my own research. I am additionally appreciative of Hugh Miller and Jennifer Parks for raising questions at my proposal defense that helped to make my final project stronger. -

12-05-2008.Pdf2013-02-12 15:4711.4 MB

ISIE: 2 OICES AAIC SEACOAS OIAYS l lvr fr G O AGE A IAY, ECEME , 2008 8A, A8A O OU rntdEWS I Et Kntn I Extr I Grnlnd I ptn I ptn h I ptn ll vl. 4 I . 4 24 Knntn I fld I rth ptn I I h I Sbr I Sth ptn I Strth SEACOAS OIAY SECIO Cnnll Cntn C j. I .Atlnt. I 0 El Strt, Slbr, MA 02 I (60 26 I EE • AKE OE SbK Shl rt Offr n thbt In th rr I br Shl r Offr h fnrprnt ntr hl prn Chld Sft I Kt. Offr h, h ptrd th Sbr tt Offr hn Mn, l dtrbtd lr t t th r SES Sft . nd th lAr nd t r bt th SO tpl hl d n th nth f 2 n A6A nd 2A22A. — Atlnt ht State reports first flu case I EMO Cnt dlt. W n t nl AAIC EWS SA WIE h n ttr f t bfr th "WE KEW nflnz h ht th frd lt b th fl rrvd hr n I WAS OY • Grnt Stt. bl lth brt phr," d S Ardn t th r. In n th ff Cnr hl A MAE O prtnt f lth nd l nnnnt, IMS rnp. n Srv (S, ntd tht th tn fr Cd b vr, IME." OOK WOS EE — St f fl l Arthr th frt f nflnz th frt f th fl nflnz hhl n (ptrd h p n th St drn th Chrt n phr fr fr 2008 rlr thn lt t lln, prdn n. -

Spirit Week! the Science Behind Happiness a Look at “Soaring Valor”

The Knight Magazine November 2017 1 NOVEMBER 2017 A DISCUSSION ABOUT GUN OWNERSHIP THE KNIGHT MAGAZINE Spirit Week! The Science Behind Happiness A Look At “Soaring Valor” PLUS: Student Spotlight on Photography Girls Golf & Boys Varsity Water Polo Letter from the Editors Hello, fellow students. We want to thank you for such a positive reception to our first issue of the Knight Magazine this year. We have been working non-stop since the previous magazine was published, and hope that you enjoy this one as much as its predecessor. In this issue we tackle issues like gun ownership, the ever-threatening opioid epidemic, and the increase of American troops in Afghanistan. On the lighter side, we hope you enjoy the Spirit Week pictorial put together by the new Publications Club, as well as some Thanksgiving recipes. It is no secret that a lot has happened since our last update. Between the tragic massacre in Las Vegas, the many hurricanes that have pummeled American shores, and a Dodgers World Series loss in Game 7, just to name a few events. As your Editors-in-Chief, we continue to try to promote healthy debate within our student body. For stories published more frequently, visit our school blog at ndhsmedia.com. If you want to be a part of this Notre Dame Publications mission, please see Mrs. Landinguin or Mrs. Moulton in room 40. Your Editors, Bridget Gehan ‘18 and Maria Thomas ‘18 THE KNIGHT MAGAZINE BRIDGET GEHAN ‘18 CO-EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MARIA THOMAS ‘18 CO-EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MARIA GUINNIP ‘20 Staff Writer BLATHNAID HEANEY ‘19 Staff Writer ASHWIN MILLS ‘18 Staff Writer SARAH O’BRIEN ‘19 Staff Writer DOMINIC PALOSZ ‘18 Staff Writer DANI POSIN ‘18 Staff Writer ALLYSON ROCHE ‘19 Staff Writer EVIN SANTANA ‘19 Staff Writer CHRISTINA SHIRLEY ‘18 Staff Writer MRS. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Constructed Situations: a New History of the Situationist International

ConstruCted situations Stracey T02909 00 pre 1 02/09/2014 11:39 Marxism and Culture Series Editors: Professor Esther Leslie, Birkbeck, University of London Professor Michael Wayne, Brunel University Red Planets: Marxism and Science Fiction Edited by Mark Bould and China Miéville Marxism and the History of Art: From William Morris to the New Left Edited by Andrew Hemingway Magical Marxism: Subversive Politics and the Imagination Andy Merrifield Philosophizing the Everyday: The Philosophy of Praxis and the Fate of Cultural Studies John Roberts Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture Gregory Sholette Fredric Jameson: The Project of Dialectical Criticism Robert T. Tally Jr. Marxism and Media Studies: Key Concepts and Contemporary Trends Mike Wayne Stracey T02909 00 pre 2 02/09/2014 11:39 ConstruCted situations A New History of the Situationist International Frances Stracey Stracey T02909 00 pre 3 02/09/2014 11:39 For Peanut First published 2014 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © the Estate of Frances Stracey 2014 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3527 8 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3526 1 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1223 6 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1225 0 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1224 3 EPUB eBook Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

Theatre and Transformation in Contemporary Canada

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by YorkSpace Theatre and Transformation in Contemporary Canada Robert Wallace The John P. Robarts Professor of Canadian Studies THIRTEENTH ANNUAL ROBARTS LECTURE 15 MARCH 1999 York University, Toronto, Ontario Robert Wallace is Professor of English and Coordinator of Drama Studies at Glendon College, York University in Toronto, where he has taught for over 30 years. During the 1970s, Prof. Wallace wrote five stage plays, one of which, No Deposit, No Return, was produced off- Broadway in 1975. During this time, he began writing theatre criticism and commentary for a range of newspapers, magazines and academic journals, which he continues to do today. During the 1980s, Prof. Wallace simultaneously edited Canadian Theatre Review and developed an ambitious programme of play publishing for Coach House Press. During the 1980s, Prof. Wallace also contributed commentary and reviews to CBC radio programs including Stereo Morning, State of the Arts, The Arts Tonight and Two New Hours; for CBC-Ideas, he wrote and produced 10 feature documentaries about 20th century performance. Robert Wallace is a recipient of numerous grants and awards including a Canada Council Aid to Artists Grant and a MacLean-Hunter Fellowship in arts journalism. His books include The Work: Conversations with English-Canadian Playwrights (1982, co-written with Cynthia Zimmerman), Quebec Voices (1986), Producing Marginality: Theatre 7 and Criticism in Canada (1990) and Making, Out: Plays by Gay Men (1992). As the Robarts Chair in Canadian Studies at York (1998-99), Prof. Wallace organized and hosted a series of public events titled “Theatre and Trans/formation in Canadian Culture(s)” that united theatre artists, academics and students in lively discussions that informed his ongoing research in the cultural formations of theatre in Canada. -

Artsnews SERVING the ARTS in the FREDERICTON REGION September 22, 2016 Volume 17, Issue 37

ARTSnews SERVING THE ARTS IN THE FREDERICTON REGION September 22, 2016 Volume 17, Issue 37 In this issue *Click the “Back to top” link after each notice to return to “In This Issue”. Upcoming Events 1. Centre communautaire Sainte-Anne’s launches the 2016-17 Season with Cy & Christian KIT Goguen Sept 22 2. The UNB Art Centre presents The Next Chapter & The Stained Glass Windows of Memorial Hall Sept 23 3. Marimba Duo Taktus perform Glass Houses for Marimba Sept 22 4. Kenny James and Carla Bonnell at Grimross Brewing Co. Sept 23 5. Public Lecture: Goddesses, Whores, Vampyres & Archaeologists: Uncovering Ancient Mytilene Sept 23 6. Gardenfest Music Festival Sept 24 7. Spotlight Series presents Joe Ink at The Playhouse Sept 24 8. The Motorleague & Brother at The Capital Sept 24 9. TNB Open Space Theatre Tours Available Sept 25 10. iTrombini Chamber Music Concert at Brunswick Street Baptist Church Sept 25 11. Monday Night Film Series presents The Man Who Knew Infinity (Sept 26) & Sunset Song (Oct 3) 12. Registration Continues for the Fredericton Choral Society Sept 27 13. Potted Potter at The Playhouse Sept 27 14. Music on the Hill presents Dissonant Grooves at Memorial Hall Sept 28 15. Marty Haggard at The Playhouse Sept 29 16. Stand-up Comic Korine Côté at Centre Communautaire Sainte-Anne Sept 29 17. Music Runs Through It presents Scott Cook at Corked Wine Bar Sept 29 18. New Brunswick Media Co-Op Annual General Meeting Sept 29 19. Tenor Marcel d’Entremont at Christ Church Parish Church Sept 30 20.