Theatre and Transformation in Contemporary Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journaux Journals

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 37th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 37e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 12 No 12 Tuesday, February 13, 2001 Le mardi 13 février 2001 10:00 a.m. 10 heures The Clerk informed the House of the unavoidable absence of the Le Greffier informe la Chambre de l’absence inévitable du Speaker. Président. Whereupon, Mr. Kilger (Stormont — Dundas — Charlotten- Sur ce, M. Kilger (Stormont — Dundas — Charlottenburgh), burgh), Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees of the Vice–président et président des Comités pléniers, assume la Whole, took the Chair, pursuant to subsection 43(1) of the présidence, conformément au paragraphe 43(1) de la Loi sur le Parliament of Canada Act. Parlement du Canada. PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES PRESENTING REPORTS FROM COMMITTEES PRÉSENTATION DE RAPPORTS DE COMITÉS Mr. Lee (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the M. Lee (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Government in the House of Commons), from the Standing Chambre des communes), du Comité permanent de la procédure et Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, presented the des affaires de la Chambre, présente le 1er rapport de ce Comité, 1st Report of the Committee, which was as follows: dont voici le texte : The Committee recommends, pursuant to Standing Orders 104 Votre Comité recommande, conformément au mandat que lui and 114, that the list of members and associate members for confèrent les articles 104 et 114 du Règlement, que la liste -

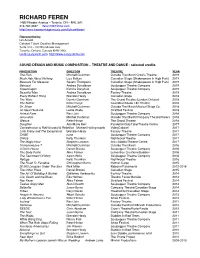

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, on – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected]

RICHARD FEREN 146B Rhodes Avenue – Toronto, ON – M4L 3A1 416-787-0657 [email protected] http://www.haemorrhage-music.com/richard-feren/ Represented by: Ian Arnold Catalyst Talent Creative Management Suite 310 - 100 Broadview Ave Toronto, Ontario Canada M4M 3H3 [email protected] http://www.catalysttcm.com SOUND DESIGN AND MUSIC COMPOSITION – THEATRE AND DANCE - selected credits PRODUCTION DIRECTOR THEATRE YEAR The Flick Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Crow’s Theatre 2019 Much Ado About Nothing Liza Balkan Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Measure For Measure Severn Thompson Canadian Stage (Shakespeare In High Park) 2019 Betrayal Andrea Donaldson Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Copenhagen Katrina Darychuk Soulpepper Theatre Company 2019 Beautiful Man Andrea Donaldson Factory Theatre 2019 Every Brilliant Thing Brendan Healy Canadian Stage 2018 The Wars Dennis Garnhum The Grand Theatre (London Ontario) 2018 The Nether Peter Pasyk Coal Mine/Studio 180 Theatre 2018 Dr. Silver Mitchell Cushman Outside The March/Musical Stage Co. 2018 An Ideal Husband Lezlie Wade Stratford Festival 2018 Animal Farm Ravi Jain Soulpepper Theatre Company 2018 Jerusalem Mitchel Cushman Outside The March/Company Theatre/Crow’s 2018 Silence Peter Hinton The Grand Theatre 2018 Daughter Ann-Marie Kerr Pandemic/QuipTake/Theatre Centre 2017 Confederation & Riel/Scandal & Rebellion Michael Hollingsworth VideoCabaret 2017 Little Pretty and The Exceptional Brendan Healy Factory Theatre 2017 CAGE none Soulpepper Theatre Company 2017 Unholy Kelly Thornton -

BACKBENCHERS So in Election Here’S to You, Mr

Twitter matters American political satirist Stephen Colbert, host of his and even more SPEAKER smash show The Colbert Report, BACKBENCHERS so in Election Here’s to you, Mr. Milliken. poked fun at Canadian House Speaker Peter politics last week. p. 2 Former NDP MP Wendy Lill Campaign 2011. p. 2 Milliken left the House of is the writer behind CBC Commons with a little Radio’s Backbenchers. more dignity. p. 8 COLBERT Heard on the Hill p. 2 TWITTER TWENTY-SECOND YEAR, NO. 1082 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, APRIL 4, 2011 $4.00 Tories running ELECTION CAMPAIGN 2011 Lobbyists ‘pissed’ leaner war room, Prime Minister Stephen Harper on the hustings they can’t work on focused on election campaign, winning majority This campaign’s say it’s against their This election campaign’s war room Charter rights has 75 to 90 staffers, with the vast majority handling logistics of about one man Lobbying Commissioner Karen the Prime Minister’s tour. Shepherd tells lobbyists that working on a political By KRISTEN SHANE and how he’s run campaign advances private The Conservatives are running interests of public office holder. a leaner war room and a national campaign made up mostly of cam- the government By BEA VONGDOUANGCHANH paign veterans, some in new roles, whose goal is to persuade Canadi- Lobbyists are “frustrated” they ans to re-elect a “solid, stable Con- can’t work on the federal elec- servative government” to continue It’s a Harperendum, a tion campaign but vow to speak Canada’s economic recovery or risk out against a regulation that they a coalition government headed by national verdict on this think could be an unconstitutional Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff. -

The Killam Trusts Annual Report 2007

THE KILLAM TRUSTS ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Sarah Pace, BA (Hons) Administrative Officer to the Killam Trusts 1391 Seymour Street Halifax, NS B3H 3M6 T: (902) 494-1329 F:(902) 494-6562 [email protected] Published by the Trustees of the Killam Trusts www.killamtrusts.ca THE KILLAM TRUSTS ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Sarah Pace, BA (Hons) Administrative Officer to the Killam Trusts 1391 Seymour Street Halifax, NS B3H 3M6 T: (902) 494-1329 F:(902) 494-6562 [email protected] Published by the Trustees of the Killam Trusts www.killamtrusts.ca 2007 Annual Report of The Killam Trustees 2007 Annual Report of The Killam Trustees With infinite sadness, we record that our beloved fellow Trustee, W. Robert Wyman, passed away in June. A few weeks before his death, Dr. Indira Samarasekera, President and Vice Chancellor of the University of Alberta and Dr. Mark Dale, Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, journeyed to Vancouver to con- fer an honourary LLD degree on Bob at his home. At the U of A Special Convocation held in Edmonton later in the year, Bob’s wife Donna and daughter Robin told us of his deep satisfaction at having received this honour from the university of his birthplace and childhood, the city of Edmonton. Please see page 17 for a more detailed tribute to this remarkable Canadian and his inestimable contribution to higher education in Canada. Moncton, New Brunswick is a medium-sized but up and coming city. Its recent growth rests on three promising features: its loca- tion at the transportation hub of the Maritime Provinces; its highly entrepreneurial citizenry; and a thriving cultural life. -

Drew Hayden Taylor, Native Canadian Playwright in His Times

BRIDGING THE GAP: DREW HAYDEN TAYLOR, NATIVE CANADIAN PLAYWRIGHT IN HIS TIMES Dale J. Young A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2005 Committee: Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor Dr. Lynda Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Jonathan Chambers Bradford Clark © 2005 Dale Joseph Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor In his relatively short career, Drew Hayden Taylor has amassed a significant level of popular and critical success, becoming the most widely produced Native playwright in the world. Despite nearly twenty years of successful works for the theatre, little extended academic discussion has emerged to contextualize Taylor’s work and career. This dissertation addresses this gap by focusing on Drew Hayden Taylor as a writer whose theatrical work strives to bridge the distance between Natives and Non-Natives. Taylor does so in part by humorously demystifying the perceptions of Native people. Taylor’s approaches to humor and demystification reflect his own approaches to cultural identity and his expressions of that identity. Initially this dissertation will focus briefly upon historical elements which served to silence Native peoples while initiating and enforcing the gap of misunderstanding between Natives and non-Natives. Following this discussion, this dissertation examines significant moments which have shaped the re-emergence of the Native voice and encouraged the formation of the Contemporary Native Theatre in Canada. Finally, this dissertation will analyze Taylor’s methodology of humorous demystification of Native peoples and stories on the stage. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre’S John Hirsch Mainstage

ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 The Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre’s John Hirsch Mainstage. PHOTO BY JERRY GRAJEWSKI Inset: John Hirsch and Tom Hendry. Mandate It is the aim of the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre to study, practice and promote all aspects of the dramatic art, with particular emphasis on professional production. Mission The Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre exists to celebrate the widest spectrum of theatre art. Deeply rooted in the province of Manitoba, which gave it life and provides for its growth, Royal MTC aspires to both ABOUT ROYAL MTC reflect and engage the community it serves. When the Winnipeg Little Theatre and Theatre 77 merged to form Vision the Manitoba Theatre Centre in 1958, the goal was to produce great Royal MTC’s theatres and our province will theatre with mass appeal. Artistic Director John Hirsch and General teem with artists and audiences sharing in the act of imagining, enriching lives Manager Tom Hendry staged professional productions of an eclectic and communities. array of plays – classics, Broadway hits and new Canadian work. With the establishment of a second stage for experimental work in 1960, Values and an annual provincial tour that began in 1961, MTC fully realized Quality the original vision of a centre for theatre in Manitoba. Inspired by the A commitment to quality is reflected in the breadth and quality of MTC’s programming, a whole network of what writing of each play, in the actors, directors became known as “regional theatres” emerged across North America. and designers who create each production, and in the volunteers, staff, funders and Since its founding, MTC has produced more than 600 plays with audiences who support it. -

Total of !0 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

TOTAL OF !0 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) Liberalism in Winnipeg, 1890s-1920s: Charles W. Gordon, John W. Dafoe, Minnie J.B. Campbell, and Francis M. Beynon by © Kurt J. Korneski A thesis submitted to the school of graduate studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Memorial University of Newfoundland April2004 DEC 0 5 2005 St. John's Newfoundland Abstract During the first quarter of the twentieth century Canadians lived through, were shaped by, and informed the nature of a range of social transformations. Social historians have provided a wealth of information about important aspects of those transformations, particularly those of"ordinary" people. The purpose of this thesis is to provide further insight into these transitions by examining the lives and thoughts of a selection of those who occupied a comparatively privileged position within Canadian society in the early twentieth century. More specifically, the approach will be to examine four Winnipeg citizens - namely, Presbyterian minister and author Charles W. Gordon, newspaper editor John W. Dafoe, member of the Imperial Order Daughters of Empire Minnie J.B. Campbell, and women's page editor Francis M. Beynon. In examining these men and women, what becomes evident about elites and the social and cultural history of early twentieth-century Canada is that, despite their privileged standing, they did not arrive at "reasonable" assessments of the state of affairs in which they existed. Also, despite the fact that they and their associates were largely Protestant, educated Anglo-Canadians from Ontario, it is apparent that the men and women at the centre of this study suggest that there existed no consensus among elites about the proper goals of social change. -

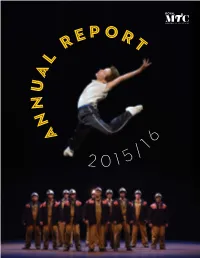

A N N U a L Report 2015/16

2 0 1 5 / 1 a 6 n n u a l R e t p r o The Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre’s John Hirsch Mainstage. PHOTO BY JERRY GRAJEWSKI Inset: John Hirsch and Tom Hendry. Mandate It is the aim of the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre to study, practice and promote all aspects of the dramatic art, with particular emphasis on professional production. Mission The Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre exists to celebrate the widest spectrum of theatre art. Deeply rooted in the province of Manitoba, which gave it life and provides for its growth, Royal MTC aspires to both ABOUT ROYAL MTC reflect and engage the community it serves. When the Winnipeg Little Theatre and Theatre 77 merged to form Vision the Manitoba Theatre Centre in 1958, the goal was to produce great Royal MTC’s theatres and our province will theatre with mass appeal. Artistic Director John Hirsch and General teem with artists and audiences sharing in the act of imagining, enriching lives Manager Tom Hendry staged professional productions of an eclectic and communities. array of plays – classics, Broadway hits and new Canadian work. With the establishment of a second stage for experimental work in 1960, Values and an annual provincial tour that began in 1961, MTC fully realized Quality the original vision of a centre for theatre in Manitoba. Inspired by the A commitment to quality is reflected in the breadth and quality of MTC’s programming, a whole network of what writing of each play, in the actors, directors became known as “regional theatres” emerged across North America. -

CANADA's ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET Thu, Oct 20, 7:30 Pm Carlson Family Stage

2016 // 17 SEASON Northrop Presents CANADA'S ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET Thu, Oct 20, 7:30 pm Carlson Family Stage DRACULA Dear Northrop Dance Lovers, Northrop at the University of Minnesota Presents It’s great to welcome Canada’s Royal Winnipeg Ballet back to Northrop! We presented their WONDERLAND at the Orpheum in 2011, but they last appeared on this stage in 2009 with their sensational Moulin Rouge. Northrop was a CANADA'S ROYAL very different venue then, and the dancers are delighting in the transformation of this historic space. The work that Royal Winnipeg brings us tonight boasts WINNIPEG BALLET quite a history as well. When it first came out in 1897, Bram th Stoker’s novel was popular enough, but it was the early 20 Under the distinguished Patronage of His Excellency century film versions that really caused its popularity to The Right Honourable David Johnston, C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.D. skyrocket. The play DRACULA appeared in London in 1924 Governor General of Canada and had a successful three-year tour, and then the American version opened in New York City in 1927 and grossed over $2 Founders, GWENETH LLOYD & BETTY FARRALLY million in its first year (that’s in 1927 dollars, and 1927 ticket Artistic Director Emeritus, ARNOLD SPOHR, C.C., O.M. prices). Founding Director, School Professional Division, DAVID MORONI, C.M. Founding Director, School Recreational Division, JEAN MACKENZIE Christine Tschida. Photo by Tim Rummelhoff. So, what is it about this vampire tale that still evokes dread and horror, but most of all, fascination? That’s a subject Artistic Director currently being explored by our first University Honors Program-coordinated interdisciplinary, outside- ANDRÉ LEWIS the-classroom Honors Experience: Dracula in Multimedia. -

The Cbc Radio Drama Project and Its Background

THE CBC RADIO DRAMA PROJECT AND ITS BACKGROUND by Howard Fink Radio drama for me, as for many people who were growing up just after the War, was, quite simply, my introduction to theatre: the classics, Renaissance drama, and modern and contemporary plays, including European and Canadian. It is rare that one gets the opportunity to re-examine a major formative influence later in one's life, rarer still to find that in this objective light its value holds up. I have had that happy experience with CBC radio drama. I have also had an experience of a completely different kind, in attempting to trace the materials of this influ- ential phenomenon: one which, as regards the history of Canadian theatre in general, has been shared in some measure by many: it was almost impossible to study the achievement of CBC radio drama as a whole, or even at first to locate the vast majority of the plays created and produced. Of course this is partly owing to the particular nature of theatre, the original form of which, unlike a novel or a book of verse, is a live performance, which remains rather in the memories than in the bookcases of its audience. More particularly, the CBC has always considered itself a production organization rather than a repository of culture, and quite rightly so. It has, in fact, been discouraged from archival activities by the government, which considers the Public Archives of Canada as a more appropriate institution for that role. 3f course such well-known figures as Robertson Davies, George Ryga and James Reaney are well represented in print. -

MANGAARD C.V 2019 (6Pg)

ANNETTE MANGAARD Film/Video/Installation/Photography Born: Lille Værløse, Denmark. Canadian Citizen Education: MFA, Gold Medal Award, OCAD University 2017 BIO Annette Mangaard is a Danish born Canadian media artist and filmmaker who has recently completed her Masters in Interdisciplinary Art, Media and Design. Her installation work has been shown around the world including: the Armoury Gallery, Olympic Site in Sydney Australia; Pearson International Airport, Toronto; South-on Sea, Liverpool and Manchester, UK; Universidad Nacional de Río Negro, Patagonia, Argentina; and Whitefish Lake, First Nations, Ontario. Mangaard has completed more then 16 films in more than a decade as an independent filmmaker. Her feature length experimental documentary on photographer Suzy Lake and the history of feminism screened as part of the INTRODUCING SUZY LAKE exhibition October 2014 through March 2015 at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Mangaard was nominated for a Gemini for Best Director of a Documentary for her one hour documentary, GENERAL IDEA: ART, AIDS, AND THE FIN DE SIECLE about the celebrated Canadian artists collective which premiered at Hot Doc’s in Toronto then went on to garner accolades around the world. Mangaard’s one hour documentary KINNGAIT: RIDING LIGHT INTO THE WORLD, about the changing face of the Inuit artists of Cape Dorset premiered at the Art Gallery of Ontario and was invited to Australia for a special screening celebrating Canada Day with the Canadian High Commission. Mangaard’s body of work was presented as a retrospective at the Palais de Glace, Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2009 and at the PAFID, Patagonia, Argentina in 2013. In 1990 Mangaard was invited to present solo screenings of her films at the Pacific Cinematheque in Vancouver, Canada and in 1991 at the Kino Arsenal Cinematheque in Berlin, West Germany. -

The Last Comedy

v*? - at \ The Banff Centre for Continuing Education T h e B a n f f C e n t r e As The Banff Centre embarks on its seventh decade, it carries with it a new image as an internationally renowned centre of creativity. presents The Centre continues to stress the imagina tion's role in a vibrant and prosperous soci ety. It champions artists, business leaders and their gift of creativity. It brings profes The Last sionals face to face with new ideas, catalyses achievement, experiments with disciplinary boundaries. It takes Canadians and others to the cutting edge - and beyond. Comedy The Banff Centre operates under the authority of The Banff Centre Act, Revised by Michael Mackenzie Statutes of Alberta. For more information call: Arts Programs 762-6180 Gallery Information 762-6281 Management Programs 762-6129 Directed by - Jean Asselin Conference Services 762-6204 Set and Costume Design by - Patrick Clark Lighting Design by - Harry Frehner Set and Costume Design Assistant - Julie Fox* Lighting Design Assistant - Susann Hudson* Arts Focus Stage Manager - Winston Morgan+ Our Centre is a place for artists. The Assistant Stage Manager - Jeanne LeSage*+ Banff Centre is dedicated to lifelong Production Assistant - David Fuller * learning and professional career develop ment for artists in all their diversity. * A resident in training in the Theatre Production, We are committed to being a place that Design and Stage Management programs. really works as a catalyst for creative +Appearing through the courtesy of the Canadian activity — a place where artistic practices Actors' Equity Association are broadened and invigorated. There will be one fifteen minute intermission Interaction with a live audience is an important part of many artists’ profession al development.