The Search for the Authentic Citron (Citrus Medica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bright Citron™ Soak

Product Profile BRIGHT CITRON™ SOAK WHAT IT IS An aromatic and refreshing sea salt soak for cleansing skin. WHAT IT DOES Softens and cleanses skin. WHY YOU NEED IT • Provides the first step to cleanse impurities and soften skin for a luxurious manicure or pedicure experience. • Gently cleanses without drying skin. FRAGRANCE FEATURED Pink Grapefruit and Warm Amber. FRAGRANCE PROFILE • Bright citrus top notes. • Soft floral mid notes. CREATIVE SUGGESTIONS • Light woody base notes. • Create a fragrant ceremonial experience by placing the Soak into warm water directly prior to ACTIVE BOTANICALS immersing hands or feet. Kaffir Lime (Citrus Hystrix Leaf Extract): • Add lime or grapefruit slices to enhance the Is known to purify skin and promote radiance. experience. • Use as a foot soak prior to all salon services. Honey: • Excellent retail product for home use in bath tubs. Is known to hydrate skin and help retain moisture. INGREDIENT LISTING FEATURED INGREDIENTS & BENEFITS Maris Sal ((Sea Salt) Sel Marin), Sodium Sesquicarbonate, Sea Salt: Argania Spinosa Kernel Oil, Honey, Citrus Hystrix Leaf Natural salt used for its therapeutic properties. Extract, Aqua ((Water) Eau), Glycerin, Propylene Glycol, Salts increase the flow of water in and out of Hydrated Silica, Parfum (Fragrance), Limonene, Linalool, cells, in essence flushing and cleansing the cells. Hexyl Cinnamal, Citral. This facilitates the absorption of other ingredients into the cells. AVAILABLE SIZES • Retail/Professional: 410 g (14.4 oz) Argan Oil (Argania Spinosa Kernel Oil): • Professional: 3.3 kg (118.8 oz) Is known to nourish dry skin. DIRECTIONS FOR USE • For feet, add a teaspoon to footbath and agitate water to dissolve. -

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 1

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Lecture 32 Citrus Citrus: Citrus spp., Rutaceae Citrus are subtropical, evergreen plants originating in southeast Asia and the Malay archipelago but the precise origins are obscure. There are about 1600 species in the subfamily Aurantioideae. The tribe Citreae has 13 genera, most of which are graft and cross compatible with the genus Citrus. There are some tropical species (pomelo). All Citrus combined are the most important fruit crop next to grape. 1 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 The common features are a superior ovary on a raised disc, transparent (pellucid) dots on leaves, and the presence of aromatic oils in leaves and fruits. Citrus has increased in importance in the United States with the development of frozen concentrate which is much superior to canned citrus juice. Per-capita consumption in the US is extremely high. Citrus mitis (calamondin), a miniature orange, is widely grown as an ornamental house pot plant. History Citrus is first mentioned in Chinese literature in 2200 BCE. First citrus in Europe seems to have been the citron, a fruit which has religious significance in Jewish festivals. Mentioned in 310 BCE by Theophrastus. Lemons and limes and sour orange may have been mutations of the citron. The Romans grew sour orange and lemons in 50–100 CE; the first mention of sweet orange in Europe was made in 1400. Columbus brought citrus on his second voyage in 1493 and the first plantation started in Haiti. In 1565 the first citrus was brought to the US in Saint Augustine. 2 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Taxonomy Citrus classification based on morphology of mature fruit (e.g. -

Canker Resistance: Lesson from Kumquat by Naveen Kumar, Bob Ebel the Development of Asiatic Citrus Throughout Their Evolution, Plants and P.D

Canker resistance: lesson from kumquat By Naveen Kumar, Bob Ebel The development of Asiatic citrus Throughout their evolution, plants and P.D. Roberts canker in kumquat leaves produced have developed many defense mecha- anthomonas citri pv. citri (Xcc) localized yellowing (5 DAI) or necro- nisms against pathogens. One of the is the causal agent of one of sis (9-12 DAI) that was restricted to most characteristic features associated the most serious citrus diseases the actual site of inoculation 7-12 DAI with disease resistance against entry X (Fig. 2). of a pathogen is the production of worldwide, Asiatic citrus canker. In the United States, Florida experienced In contrast, grapefruit epidermis hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Hydrogen three major outbreaks of Asiatic citrus became raised (5 DAI), spongy (5 peroxide is toxic to both plant and canker in 1910, 1984 and 1995, and it DAI) and ruptured from 7 to 8 DAI. pathogen and thus restricts the spread is a constant threat to the $9 billion On 12 DAI, the epidermis of grape- by directly killing the pathogen and citrus industry. fruit was thickened, corky, and turned the infected plant tissue. Hydrogen Citrus genotypes can be classified brown on the upper side of the leaves. peroxide concentrations in Xcc-in- into four broad classes based on sus- Disease development and popula- fected kumquat and grapefruit leaves ceptibility to canker. First, the highly- tion dynamics studies have shown that were different. Kumquat produces susceptible commercial genotypes are kumquat demonstrated both disease more than three times the amount of Key lime, grapefruit and sweet lime. -

Citrus from Seed?

Which citrus fruits will come true to type Orogrande, Tomatera, Fina, Nour, Hernandina, Clementard.) from seed? Ellendale Tom McClendon writes in Hardy Citrus Encore for the South East: Fortune Fremont (50% monoembryonic) “Most common citrus such as oranges, Temple grapefruit, lemons and most mandarins Ugli Umatilla are polyembryonic and will come true to Wilking type. Because most citrus have this trait, Highly polyembryonic citrus types : will mostly hybridization can be very difficult to produce nucellar polyembryonic seeds that will grow true to type. achieve…. This unique characteristic Citrus × aurantiifolia Mexican lime (Key lime, West allows amateurs to grow citrus from seed, Indian lime) something you can’t do with, say, Citrus × insitorum (×Citroncirus webberii) Citranges, such as Rusk, Troyer etc. apples.” [12*] Citrus × jambhiri ‘Rough lemon’, ‘Rangpur’ lime, ‘Otaheite’ lime Monoembryonic (don’t come true) Citrus × limettioides Palestine lime (Indian sweet lime) Citrus × microcarpa ‘Calamondin’ Meyer Lemon Citrus × paradisi Grapefruit (Marsh, Star Ruby, Nagami Kumquat Redblush, Chironja, Smooth Flat Seville) Marumi Kumquat Citrus × sinensis Sweet oranges (Blonde, navel and Pummelos blood oranges) Temple Tangor Citrus amblycarpa 'Nasnaran' mandarin Clementine Mandarin Citrus depressa ‘Shekwasha’ mandarin Citrus karna ‘Karna’, ‘Khatta’ Poncirus Trifoliata Citrus kinokuni ‘Kishu mandarin’ Citrus lycopersicaeformis ‘Kokni’ or ‘Monkey mandarin’ Polyembryonic (come true) Citrus macrophylla ‘Alemow’ Most Oranges Citrus reshni ‘Cleopatra’ mandarin Changshou Kumquat Citrus sunki (Citrus reticulata var. austera) Sour mandarin Meiwa Kumquat (mostly polyembryonic) Citrus trifoliata (Poncirus trifoliata) Trifoliate orange Most Satsumas and Tangerines The following mandarin varieties are polyembryonic: Most Lemons Dancy Most Limes Emperor Grapefruits Empress Tangelos Fairchild Kinnow Highly monoembryonic citrus types: Mediterranean (Avana, Tardivo di Ciaculli) Will produce zygotic monoembryonic seeds that will not Naartje come true to type. -

Growing Citrus in the North Bay

Growing Citrus in the North Bay Steven Swain UC Cooperative Extension, Marin & Sonoma Counties (415) 473-4204 [email protected] http://cemarin.ucanr.edu The title is almost an oxymoron Where do citrus trees come from? . Southeast Asia . Burma (Myanmar) . Yunnan province of China . Northeast India In California, we’re used to being able to grow anything . But California’s famous for lots of climates in a small area Where is citrus Sacramento Valley: 0.4% commercially grown? Not here … San Joaquin Valley: 73% . There’s probably more than one reason for that Desert Valleys: 5% . Commercial citrus in Sacramento Valley is restricted to hot spots . Commercial grapefruit restricted to inland locations with water – Why? Coast: 12% . Citrus is a subtropical plant – It needs heat to produce sugar South Coast And Interior: 10% Citrus development periods Development Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec prebloom shoot growth and leaf flush bloom petal fall, leaf drop (?) root growth fruit drop fruit development slow increase in size rapid increase in size maturation, slow increase … for navel oranges grown in San Joaquin County The average time of year for each development stage is shown in dark gray, less vigorous development is shown in light gray Note early drop (light gray), June drop (dark gray), and preharvest drop (light gray) Prebloom: All citrus except lemon essentially stop growing in California’s climate (variable due to weather) Note that maturation can extend into early May in some citrus varietals in some regions Table adapted from IPM for Citrus, 3rd ed., in turn from Lovatt, in prep From: Bower JP (2004) The pre- and postharvest application potential for CropSet and ISR2000 on citrus. -

Chemical Variability of Peel and Leaf Essential Oils in the Citrus Subgenus Papeda (Swingle) and Few Relatives

plants Article Chemical Variability of Peel and Leaf Essential Oils in the Citrus Subgenus Papeda (Swingle) and Few Relatives Clémentine Baccati 1, Marc Gibernau 1, Mathieu Paoli 1 , Patrick Ollitrault 2,3 ,Félix Tomi 1,* and François Luro 2 1 Laboratoire Sciences Pour l’Environnement, Equipe Chimie et Biomasse, Université de Corse—CNRS, UMR 6134 SPE, Route des Sanguinaires, 20000 Ajaccio, France; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (M.P.) 2 UMR AGAP Institut, Université Montpellier, CIRAD, INRAE, Institut Agro, 20230 San Giuliano, France; [email protected] (P.O.); [email protected] (F.L.) 3 CIRAD, UMR AGAP, 20230 San Giuliano, France * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-495-52-4122 Abstract: The Papeda Citrus subgenus includes several species belonging to two genetically distinct groups, containing mostly little-exploited wild forms of citrus. However, little is known about the potentially large and novel aromatic diversity contained in these wild citruses. In this study, we characterized and compared the essential oils obtained from peels and leaves from representatives of both Papeda groups, and three related hybrids. Using a combination of GC, GC-MS, and 13C-NMR spectrometry, we identified a total of 60 compounds in peel oils (PO), and 76 compounds in leaf oils (LO). Limonene was the major component in almost all citrus PO, except for C. micrantha and C. hystrix, where β-pinene dominated (around 35%). LO composition was more variable, with different Citation: Baccati, C.; Gibernau, M.; major compounds among almost all samples, except for two citrus pairs: C. -

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Presentation

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Citrus species & Citrus Relatives Hundreds of varieties available. CITRON Citrus medica • The citron is believed to be one of the original kinds of citrus. • Trees are small and shrubby with an open growth habit. The new growth and flowers are flushed with purple and the trees are sensitive to frost. • Ethrog or Etrog citron is a variety of citron commonly used in the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles. The flesh is pale yellow and acidic, but not very juicy. The fruits hold well on the tree. The aromatic fruit is considerably larger than a lemon. • The yellow rind is glossy, thick and bumpy. Citron rind is traditionally candied for use in holiday fruitcake. Ethrog or Etrog citron CITRON Citrus medica • Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron is a unique citrus grown mainly as a curiosity. The six to twelve inch fruits are apically split into a varying number of segments that are reminiscent of a human hand. • The rind is yellow and highly fragrant at maturity. The interior of the fruit is solid rind with no flesh or seeds. • Fingered citron fruits usually mature in late fall to early winter and hold moderately well on the tree, but not as well as other citron varieties. Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron NAVEL ORANGES Citrus sinensis • ‘Washington navel orange’ is also known • ‘Lane Late Navel’ was the first of a as the Bahia. It was imported into the number of late maturing Australian United States in 1870. navel orange bud sport selections of Washington navel imported into • These exceptionally delicious, seedless, California. -

A New Graft Transmissible Disease Found in Nagami Kumquat L

A New Graft Transmissible Disease Found in Nagami Kumquat L. Navarro, J. A. Pina, J. F. Ballester, P. Moreno, and M. Cambra ABSTRACT. An undescribed graft transmissible disease has been found on Nagami kumquat. Three types of symptoms have been observed: 1) vein clearing on Pineapple sweet orange, Troyer citrange, sour orange, Marsh grapefruit, Orlando tangelo, Dweet tangor and Alemow, but not on Mexican lime, Etrog citron, Cleopatra mandarin, rough lemon, Eureka lemon, Volkamer lemon, trifoliate orange, Nules clementine and Parson's special mandarin; 2) stem pitting on Etrog citron, but not on the other species and hybrids; and 3) graft incompatibility of Nagami kumquat on Troyer citrange, but not on rough lemon. Vein clearing symptoms were more severe in seedlings grown at 18- 25OC than at 27-32OC. Stem pitting was induced only at 18-25OC. Some kumquat plants obtained by shoot-tip grafting in vitro were compatible with Troyer citrange, and did not induce vein clearing, but still produced stem pitting. These data suggest the presence of more than one pathogen on the original plants. Preliminary electron micro- scopy studies have shown the presence of some virus-like particles about 800 nm long in extracts of infected Troyer citrange and sweet orange plants. Diseased kumquats gave negative reactions by ELISA using four different tristeza antisera. A Citrus Variety Improvement cortis, but it also induced vein Program (CVIPS) was started in clearing on Pineapple sweet orange. Spain in 1975 to recover virus-free This type of vein clearing symp- plants from all commercial varie- toms on sweet orange are usually ties and other citrus species, valu- not induced by tristeza in Spain. -

Citrus Trees Grow Very Well in the Sacramento Valley!

Citrus! Citrus trees grow very well in the Sacramento Valley! They are evergreen trees or large shrubs, with wonderfully fragrant flowers and showy fruit in winter. There are varieties that ripen in nearly every season. Citrus prefer deep, infrequent waterings, regular fertilizer applications, and may need protection from freezing weather. We usually sell citrus on rootstocks that make them grow more slowly, so we like to call them "semi-dwarf". We can also special-order most varieties on rootstocks that allow them to grow larger. Citrus size can be controlled by pruning. The following citrus varieties are available from the Redwood Barn Nursery, and are recommended for our area unless otherwise noted in the description. Oranges Robertson Navel Best selling winter-ripening variety. Early and heavy bearing. Cultivar of Washington Navel. Washington Navel California's famous winter-ripening variety. Fruit ripens in ten months. Jaffa (Shamouti) Fabled orange from Middle East. Very few seeds. spring to summer ripening. Good flavor. Trovita Spring ripening. Good in many locations from coastal areas to desert. Few seeds, heavy producer, excellent flavor. Valencia Summer-ripening orange for juicing or eating. Fifteen months to ripen. Grow your own orange juice. Seville Essential for authentic English marmalade. Used fresh or dried in Middle Eastern cooking. Moro Deep blood coloration, almost purple-red, even in California coastal areas. Very productive, early maturity, distinctive aroma, exotic berry-like flavor. Sanquinella A deep blood red juice and rind. Tart, spicy flavor. Stores well on tree. Mandarins / Tangerines Dancy The best-known Mandarin type. On fruit stands at Christmas time. -

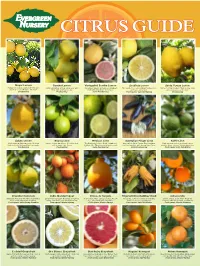

Citrus Guide

CITRUS GUIDE Meyer Lemon Eureka Lemon Variegated Eureka Lemon Seedless Lemon Santa Teresa Lemon Popular in recipes. Juicy with thin skin Common market lemon. Very juicy with Variegated leaves and yellow, streaked The hassle-free lemon. Bright yellow rind Native to Italy. Medium-thick yellow rinds and few seeds. Medium size fruit. thick skin and few seeds. fruit with pink flesh. Very juicy. with tart, juicy flesh. with very juicy, acidic flesh. Everbearing Everbearing Semi-Everbearing Fruit ripens: Late Fall-Spring Everbearing Lisbon Lemon Bearss Lime Mexican Lime Australian Finger Lime Kaffir Lime Most common California lemon. Medium Larger, lemon-sized lime. Seedless fruit The Bartender’s lime. Small, round and Also called Citrus Caviar. Fruit contains Fruit used in curries; pungent leaves thick rind, pale flesh and few to no seeds. with a sweet-tart flavor. highly acidic. Thornless variety also avail. vesicles bursting with lemon-lime flavor. used in Asian cuisine. Yellow when ripe. Everbearing Everbearing Semi-Everbearing Semi-Everbearing Fruit ripens: Late Fall-Winter Chandler Pummelo Indio Mandarinquat Minneola Tangelo Fingered Citron Buddhas’ Hand Calamondin Pink flesh; thick rind with bitter membranes. Larger than kumquat. Bell shaped fruit has Red-orange, thin, easy peel rind. Sweet- Fingerlike sections consist of rind only. Small, round, acidic fruit. Great for Fruit usually segmented for eating. sweet-sour flavor; can be eaten whole. tart, juicy flesh with few seeds. Used for zest or candied rind. chutneys and marmalade. Cold hardy. Fruit ripens: Late Spring-Summer Fruit ripens: Winter-Spring Fruit ripens: Winter-Spring Fruit ripens: Late Fall-Winter Fruit ripens: Winter-Summer Cocktail Grapefruit Oro Blanco Grapefruit Star Ruby Grapefruit Nagami Kumquat Meiwa Kumquat Large fruit with thin yellow rind. -

Genomic Analyses of Primitive, Wild and Cultivated Citrus Provide Insights Into Asexual Reproduction

ARTICLES OPEN Genomic analyses of primitive, wild and cultivated citrus provide insights into asexual reproduction Xia Wang1,7, Yuantao Xu1,7, Siqi Zhang1,7, Li Cao2,7, Yue Huang1, Junfeng Cheng3, Guizhi Wu1, Shilin Tian4, Chunli Chen5, Yan Liu3, Huiwen Yu1, Xiaoming Yang1, Hong Lan1, Nan Wang1, Lun Wang1, Jidi Xu1, Xiaolin Jiang1, Zongzhou Xie1, Meilian Tan1, Robert M Larkin1, Ling-Ling Chen3, Bin-Guang Ma3, Yijun Ruan5,6, Xiuxin Deng1 & Qiang Xu1 The emergence of apomixis—the transition from sexual to asexual reproduction—is a prominent feature of modern citrus. Here we de novo sequenced and comprehensively studied the genomes of four representative citrus species. Additionally, we sequenced 100 accessions of primitive, wild and cultivated citrus. Comparative population analysis suggested that genomic regions harboring energy- and reproduction-associated genes are probably under selection in cultivated citrus. We also narrowed the genetic locus responsible for citrus polyembryony, a form of apomixis, to an 80-kb region containing 11 candidate genes. One of these, CitRWP, is expressed at higher levels in ovules of polyembryonic cultivars. We found a miniature inverted-repeat transposable element insertion in the promoter region of CitRWP that cosegregated with polyembryony. This study provides new insights into citrus apomixis and constitutes a promising resource for the mining of agriculturally important genes. Asexual reproduction is a remarkable feature of perennial fruit crops important trait for breeding purposes. On the one hand, polyembryony that facilitates the faithful propagation of commercially valuable is widely employed in citrus nurseries and propagation programs to individuals by avoiding the uncertainty associated with the sexual generate large numbers of uniform rootstocks from seeds. -

Spring Lunch Menu

Spring Lunch Menu APPETIZERS & SMALL PLATES Tuna Tartare 16 Sushi Grade Tuna, Togarashi Chips, Cucumber, Radish, Haricots Verts, Avocado Tzatziki, Kaffir Lime Vinaigrette Crispy Calamari 15 Citrus Garlic Butter, Crispy Pickled Peppers, Spicy Romanesco Black Skillet Roasted Mussels 17 Sicilian Sea Salt, Olive Oil, Citrus Heirloom Baby Carrots and Charred Brussels Sprouts 10 Almonds, Feta Cheese, Cumin-Yogurt Vinaigrette, Cilantro Mint Pesto Crispy Kettle Potato Chips 10 Maytag Bleu Cheese Fondue, Roma Tomato, Maple Cajun Bacon, Scallions Artisian Cheeses & Charcuterie to Share 25 Fresh & Dried Fruits, Nuts, Olives, Breads, Honeycomb SOUPS 9 Soup du Jour Ask Your Server SIMPLY SALADS 11 Citron Seasonal Salad Endive, Watercress, Spinach, Dried Blueberries, Green Apple, Pecan Brittle, Champagne Herb Vinaigrette Contemporary Caesar Salad Petite Romaine Lightly Grilled, Spicy Croutons, Shaved Grana Padano, Black Citrus-Garlic Dressing Wedge Classic Baby Iceberg Lettuce, Boiled Egg, Roma Tomato, Maple Cajun Bacon, Scallions, Maytag Bleu Cheese Baby Kale Salad Grilled Corn, Dried Fruit, Avocado, Cherry Tomatoes, Candied Marcona Almonds, Cilantro Buttermilk Dressing Add to Any Simply Salad… Salmon 14 Grilled Chicken 9 Chilled Shrimp 15 Sliced Angus Tenderloin 20 Soup Cup 6 ENTRÉE SALADS Crispy Buttermilk Chicken 20 Field Greens, Watercress and Baby Kale, Grilled Corn, Dried Fruit, Avocado, Cherry Tomato, Candied Marcona Almonds, Cilantro-Buttermilk Dressing Herb-Seared Rare Ahi Tuna Nicoise 25 Baby Greens, Fingerling Potato, Eggs, Tomato, French