National Communism and Soviet Strategy, by Dinko A. Tomasic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Soviet Investigation of the 1991 Coup the Suppressed Transcripts

Supreme Soviet Investigation of the 1991 Coup The Suppressed Transcripts: Part 3 Hearings "About the Illegal Financia) Activity of the CPSU" Editor 's Introduction At the birth of the independent Russian Federation, the country's most pro-Western reformers looked to the West to help fund economic reforms and social safety nets for those most vulnerable to the change. However, unlike the nomenklatura and party bureaucrats who remained positioned to administer huge aid infusions, these reformers were skeptical about multibillion-dollar Western loans and credits. Instead, they wanted the West to help them with a different source of money: the gold, platinum, diamonds, and billions of dollars in hard currency the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and KGB intelligence service laundered abroad in the last years of perestroika. Paradoxically, Western governments generously supplied the loans and credits, but did next to nothing to support the small band of reformers who sought the return of fortunes-estimated in the tens of billions of dollars- stolen by the Soviet leadership. Meanwhile, as some in the West have chronicled, the nomenklatura and other functionaries who remained in positions of power used the massive infusion of Western aid to enrich themselves-and impoverish the nation-further. In late 1995, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development concluded that Russian officials had stolen $45 billion in Western aid and deposited the money abroad. Radical reformers in the Russian Federation Supreme Soviet, the parliament that served until its building was destroyed on President Boris Yeltsin's orders in October 1993, were aware of this mass theft from the beginning and conducted their own investigation as part of the only public probe into the causes and circumstances of the 1991 coup attempt against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. -

Socialism and Current Crisis of Capitalism

providing benefits for the workers EDITORIAL who are paying into this plan." According to that law Mr. This is the last question to be Obama, it states, very, very asked of Mr. Obama: '7s the directly that: "The primary forced bankruptcy of General responsibility of the pension fund Motors and the elimination of "fiduciaries" is to run this plan tens of thousands of jobs, just solely in the interests of an arranged collection grab for participants and beneficiaries and the favored U.S. financiers that for the exclusive purpose of are calling the shots? PRESIDENT OBAMA AND THE BAIL OUT OF US AUTOMKERS This financial robbery of US and Canadian taxpayers hard- earned money is nothing more than the Greatest Auto Theft in history! Besides this unheard of Billions Robbery, it is also dumping 40,000 of the last 60,000 auto trade union jobs into the mass grave dug by Obama's appointee, James Dimon. Mr. Dimon is the CEO of J.P. Morgan and Citibank. While GM trade union workers are losing their jobs and retirement benefits, their life savings, but the GM shareholders are getting rich and most expect to get back a stunning $6 BILLION! Even under the present US Laws this is illegal! Helping Mr. Dimon is also the official Obama's appointee — This cartoon is from the Toronto Daily Star newspaper' showing Steven Rattner, Obama's "Auto the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) leadership that did not stand Czar" - the man who ordered up strongly enough during this financial robbery. Looking on is General Motors to go bankrupt. -

United We Stand, Divided We Fall: the Kremlin’S Leverage in the Visegrad Countries

UNITED WE STAND, DIVIDED WE FALL: THE KREMLIN’S LEVERAGE IN THE VISEGRAD COUNTRIES Edited by: Ivana Smoleňová and Barbora Chrzová (Prague Security Studies Institute) Authors: Ivana Smoleňová and Barbora Chrzová (Prague Security Studies Institute, Czech Republic) Iveta Várenyiová and Dušan Fischer (on behalf of the Slovak Foreign Policy Association, Slovakia) Dániel Bartha, András Deák and András Rácz (Centre for Euro-Atlantic Integration and Democracy, Hungary) Andrzej Turkowski (Centre for International Relations, Poland) Published by Prague Security Studies Institute, November 2017. PROJECT PARTNERS: SUPPORTED BY: CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 CZECH REPUBLIC 7 Introduction 7 The Role of the Russian Embassy 7 The Cultural Sphere and Non-Governmental Organizations 8 The Political Sphere 9 The Extremist Sphere and Paramilitary Groups 10 The Media and Information Space 11 The Economic and Financial Domain 12 Conclusion 13 Bibliography 14 HUNGARY 15 Introduction 15 The Role of the Russian Embassy 15 The Cultural Sphere 16 NGOs, GONGOs, Policy Community and Academia 16 The Political Sphere and Extremism 17 The Media and Information Space 18 The Economic and Financial Domain 19 Conclusion 20 Bibliography 21 POLAND 22 Introduction 22 The Role of the Russian Embassy 22 Research Institutes and Academia 22 The Political Sphere 23 The Media and Information Space 24 The Cultural Sphere 24 The Economic and Financial Domain 25 Conclusion 26 Bibliography 26 SLOVAKIA 27 Introduction 27 The Role of the Russian Embassy 27 The Cultural Sphere 27 The Political Sphere 28 Paramilitary organisations 28 The Media and Information Space 29 The Economic and Financial Domain 30 Conclusion 31 Bibliography 31 CONCLUSION 33 UNITED WE STAND, DIVIDED WE FALL: THE KREMLIN’S LEVERAGE IN THE VISEGRAD COUNTRIES IN THE VISEGRAD THE KREMLIN’S LEVERAGE DIVIDED WE FALL: UNITED WE STAND, INTRODUCTION In the last couple of months, Russian interference in the internal affairs if the Kremlin’s involvement is overstated and inflated by the media. -

Teaching International Communism Lewis F

Washington and Lee University School of Law Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons Powell Speeches Powell Papers 1-8-1961 Teaching International Communism Lewis F. Powell Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/powellspeeches Part of the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, and the International and Comparative Education Commons I i ) RICHMOND PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM January 18, 1961 Instruction On International Connnunism The purpose of this memorandum is to present an analysis of what is presently (1960-61) being taught in the Richmond Public Scho.ol System on International Connnunism. The analysis will be confined to the secondary grades, which in Richmond consist of five years of instruction from the eighth through the twelfth grades. There has never been a specific course in Richmond on International Connnunism. The courses in history and government, discussed below, contain some limited discussion of Imperial Russia or the Soviet Union or both, and there is some sketchy - almost incidental - treatment of International Connnunism and the problems created by it. As the result of a study initiated in the spring of 1960, it was concluded that the available instruction is in adequate to meet the imperative needs of our time. Inquiry through professional channels indicated that there is no recognized text book on this subject for secondary school use, and that there appear to be relatively few secondary schools • ~ in the United States which undertake much more than incidental instruction in this area. The Richmond Public School System is moving to meet this need in the following_ manner. -

Selected Bibliography

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Documents Central Committee, C.P.S.U., "The Letter of the Central CommitteeoftheC.P.S.U. to the Central Committee of the C.P.C." February 21, 1963. Reprinted in A Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement. The Letter of the C.C., C.P.C., in Reply to the Letter of the C.C., C.P.S.U., March 30, 1963. -. "Letter of the Central Committee of the C.P.S.U. of November 29, 1963, to the Central Committee of the C.P.C.," Peking Review, vol. VII, no. 19, May 8, 1964, pp. 18-21. -. "Letter of the Central Committee of the C.P.S.U. of February 22, 1964, to the Central Committee of the C.P.C." Peking Review, vol. VII, no. 19, May 8,1964, pp.22-24. -. "Letter of the Central Committee of the C.P.S.U., of March 7, 1964, to the Central Committee of the C.P.C." Peking Review, vol. VII, no. 19, May 8,1964, pp.24-27. -, and U.S.S.R. Supreme Soviet, and U.S.S.R. Council of Ministers. "On Form ing the Party-State Control Committee of the C.P.S.U. Central Committee and the U.S.S.R. Council of Ministers." Izvestia, November 28, 1962, p. 1. Central Committee, C.P.S.U. "Open Letter of the Central Committee of the Com munist Party of the Soviet Union. " To the Party Organizations and Communists of the Soviet Union. Pravda,July 14,1963. -. "Peace, Humanity, and Socialism." A Soviet Reply to the China Government's Position. -

Briefing European Parliamentary Research Service

Briefing June 2016 Russia's 2016 elections More of the same? SUMMARY On 18 September, 2016 Russians will elect representatives at federal, regional and municipal level, including most importantly to the State Duma (lower house of parliament). President Vladimir Putin remains popular, with over 80% of Russians approving of his presidency. However, the country is undergoing a prolonged economic recession and a growing number of Russians feel it is going in the wrong direction. Support for Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and ruling party United Russia has declined in recent months. Nevertheless, United Russia is likely to hold onto, and even increase its parliamentary majority, given the lack of credible alternatives. Of the tame opposition parties currently represented in the State Duma, polls suggest the far-right Liberal Democrats will do well, overtaking the Communists to become the largest opposition party. Outside the State Duma, opposition to Putin's regime is led by liberal opposition parties Yabloko and PARNAS. Deeply unpopular and disunited, these parties have little chance of breaking through the 5% electoral threshold. To avoid a repeat of the 2011–2012 post-election protests, authorities may try to prevent the blatant vote-rigging which triggered them. Nevertheless, favourable media coverage, United Russia's deep pockets and changes to electoral legislation (for example, the re-introduction of single-member districts) will give the ruling party a strong head-start. In this briefing: What elections will be held in Russia? Which parties will take part? Will elections be transparent and credible? The State Duma – the lower house of Russia's parliament. -

Yugoslav Ideology and Its Importance to the Soviet Bloc: an Analysis

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1967 Yugoslav Ideology and Its Importance to the Soviet Bloc: An Analysis Christine Deichsel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Deichsel, Christine, "Yugoslav Ideology and Its Importance to the Soviet Bloc: An Analysis" (1967). Master's Theses. 3240. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3240 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YUGOSLAV IDEOLOGY AND ITS IMPORTANCE TO THE SOVIET BLOC: AN ANALYSIS by Christine Deichsel A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo., Michigan April 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In writing this thesis I have benefited from the advice and encouragement of Professors George Klein and William A. Ritchie. My thanks go to them and the other members of my Committee, namely Professors Richard J. Richardson and Alan Isaak. Furthermore, I wish to ex press my appreciation to all the others at Western Michi gan University who have given me much needed help and encouragement. The award of an assistantship and the intellectual guidance and stimulation from the faculty of the Department of Political Science have made my graduate work both a valuable experience and a pleasure. -

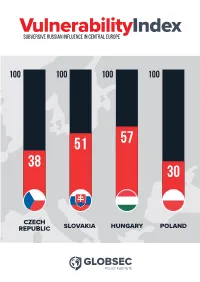

Vulnerabilityindex

VulnerabilitySUBVERSIVE RUSSIAN INFLUENCE IN CENTRAL EUROPE Index 100 100 100 100 51 57 38 30 CZECH REPUBLIC SLOVAKIA HUNGARY POLAND Credits Globsec Policy Institute, Klariská 14, Bratislava, Slovakia www.globsec.org GLOBSEC Policy Institute (formerly the Central European Policy Institute) carries out research, analytical and communication activities related to impact of strategic communication and propaganda aimed at changing the perception and attitudes of the general population in Central European countries. Authors: Daniel Milo, Senior Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Policy Institute Katarína Klingová, Research Fellow, GLOBSEC Policy Institute With contributions from: Kinga Brudzinska (GLOBSEC Policy Institute), Jakub Janda, Veronika Víchová (European Values, Czech Republic), Csaba Molnár, Bulcsu Hunyadi (Political Capital Institute, Hungary), Andriy Korniychuk, Łukasz Wenerski (Institute of Public Affairs, Poland) Layout: Peter Mandík, GLOBSEC This publication and research was supported by the National Endowment for Democracy. © GLOBSEC Policy Institute 2017 The GLOBSEC Policy Institute and the National Endowment for Democracy assume no responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication or their subsequent use. Sole responsibility lies with the authors of this publication. Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Country Overview 7 Methodology 9 Thematic Overview 10 1. Public Perception 10 2. Political Landscape 15 3. Media 22 4. State Countermeasures 27 5. Civil Society 32 Best Practices 38 Vulnerability Index Executive Summary CZECH REPUBLIC: 38 POLAND: 30 PUBLIC PERCEPTION 36 20 POLITICAL LANDSCAPE 47 28 MEDIA 34 35 STATE COUNTERMEASURES 23 33 CIVIL SOCIETY 40 53 SLOVAKIA: 51 53 HUNGARY: 57 50 31 40 78 78 60 39 80 45 The Visegrad group countries in Central Europe (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia – V4) are often perceived as a regional bloc of nations sharing similar aspirations, aims and challenges. -

Tito's Yugoslavia

The Search for a Communist Legitimacy: Tito's Yugoslavia Author: Robert Edward Niebuhr Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1953 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2008 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History THE SEARCH FOR A COMMUNIST LEGITIMACY: TITO’S YUGOSLAVIA a dissertation by ROBERT EDWARD NIEBUHR submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE ABSTRACT . iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . iv LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS . v NOTE ON TRANSLATIONS AND TERMS . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 1 A STRUGGLE FOR THE HEARTS AND MINDS: IDEOLOGY AND YUGOSLAVIA’S THIRD WAY TO PARADISE . 26 2 NONALIGNMENT: YUGOSLAVIA’S ANSWER TO BLOC POLITICS . 74 3 POLITICS OF FEAR AND TOTAL NATIONAL DEFENSE . 133 4 TITO’S TWILIGHT AND THE FEAR OF UNRAVELING . 180 5 CONCLUSION: YUGOSLAVIA AND THE LEGACY OF THE COLD WAR . 245 EPILOGUE: THE TRIUMPH OF FEAR. 254 APPENDIX A: LIST OF KEY LCY OFFICIALS, 1958 . 272 APPENDIX B: ETHNIC COMPOSITION OF JNA, 1963 . 274 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 275 INDEX . 289 © copyright by ROBERT EDWARD NIEBUHR 2008 iii ABSTRACT THE SEARCH FOR A COMMUNIST LEGITIMACY: TITO’S YUGOSLAVIA ROBERT EDWARD NIEBUHR Supervised by Larry Wolff Titoist Yugoslavia—the multiethnic state rising out of the chaos of World War II—is a particularly interesting setting to examine the integrity of the modern nation-state and, more specifically, the viability of a distinctly multi-ethnic nation-building project. -

Russian Federation

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights RUSSIAN FEDERATION STATE DUMA ELECTIONS 18 September 2016 OSCE/ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report Warsaw 23 December 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................... 3 III. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT ............................................................................... 4 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ....................................................................................................................... 5 V. ELECTORAL SYSTEM ....................................................................................................................... 6 VI. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ....................................................................................................... 7 VII. VOTER REGISTRATION .................................................................................................................... 9 VIII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION ........................................................................................................ 10 IX. CAMPAIGN ......................................................................................................................................... 12 X. CAMPAIGN FINANCE ..................................................................................................................... -

West European Communist Parties: Kautskyism And/Or Derevolutionization?

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Download Download

1 Nepali Communist Parties in Elections: Participation and Representation Amrit Kumar Shrestha, PhD Associate Professor Department of Political Science Education Central Department of Education, Kirtipur, Tribhuvan University, Nepal. Email: [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3792-0666 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/dristikon.v10i1.34537 Abstract The communist parties are not gaining popularity throughout the countries of the world, as they are shrinking. The revolutionary communist forces are in a defensive position, and the reformist communists have failed to achieve good results in the elections. Communist parties are struggling just for their existence in the developed countries. They are not in a decisive position, even in developing countries as well. Nevertheless, communists of Nepal are obtaining popularity through the elections. Although the communists of Nepal are split into many factions, they have been able to win the significant number of seats of electoral offices. This article tries to analyze the position of communist parties in the general elections of Nepal. It examines seven general elections of Nepal held from 1959 to 2017. Facts, which were published by the Elections Commission of Nepal at different times, were the basic sources of information for this article. Similarly, governmental and scholarly publications were also used in the article. Keywords: communists, revolutionary, reformist, elections, electoral office Introduction Background Tentatively, communists of the world are divided into two categories; one believes in reformation, and another emphasizes on revolution. As D'Amato (2000) stated that reformists believe in peaceful and gradual transformation. They utilize the election as a means to achieve socialism.