58303X4 10/5/07 12:42 PM Page 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surviving Nevada Railroad Stations

Surviving Nevada Railroad Stations Boulder City: The passenger station originally built by the Union Pacific here still stands, home of the Southern Nevada Museum. Caliente: The passenger station originally built by the Union Pacific Railroad here still stands. Carson City: The passenger stations originally built by the Virginia & Truckee Railroad and Nevada Copper Belt Railroad/Southern Pacific here still stand. Cherry Creek: The passenger station originally built by the Nevada Northern Railway here still stands, home of the White Pine Public Museum, moved to Ely. Currie: The passenger station originally built by the Nevada Northern Railway here still stands. Dayton: The passenger station originally built by the Southern Pacific Railroad here still stands. East Ely: The passenger and freight stations originally built by the Nevada Northern Railway here still stand, home of the East Ely Depot Railroad Museum. Elko: The passenger station originally built by the Western Pacific Railroad here still stands. Also, the freight depots built by the SP and WP here still stand. Ely: The passenger station originally built by the Nevada Northern Railway here still stands. Eureka: The passenger station originally built by the Eureka & Palisade Railroad here still stands, privately owned. Fallon: The passenger station originally built by the Southern Pacific Railroad here still stands, used as a business. Fernley: The passenger station originally built by the Southern Pacific Railroad here still stands. Gerlach: The passenger station originally built by the Western Pacific Railroad here still stands, owned by UP. Goldfield: The passenger station originally built by the Tonopah & Goldfield Railroad here still stands, used as a business. -

Nevada Northern Railway, B.A. No. 2742, Has Been Terminated As an Employer Under the Acts

EMPLOYER STATUS DETERMINATION Northern Nevada Railroad Corporation This is the determination of the Railroad Retirement Board regarding the status of Northern Nevada Railroad Corporation (NN) as an employer under the Railroad Retirement Act (45 U.S.C. §231 et seq.) (RRA) and Railroad Unemployment Insurance Act (45 U.S.C. §351 et seq.) (RUIA). NN has not previously been determined to be an employer under the RRA and the RUIA. Information about NN was furnished by Bryan R. R. Whipple, Chief Operating Officer of NN. Although NN was formed in 1991 to lease and operate the abandoned railroad properties of the former Nevada Northern Railway,1 the first compensated service performed as a rail common carrier was January 1, 1995. The rail line in question was acquired by the cities of Ely, Nevada and Los Angeles, California, and in 1993 NN obtained long-term freight operating rights from the cities. See Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) Finance Docket No. 32623, 32624 decided December 15, 1994. According to information provided by Mr. Whipple, NN began operations on January 1, 1995, and has nine employees who were compensated for rail carrier service from that same date. Mr. Whipple stated that the line in question interchanges with the Union Pacific Railroad, and by late 1995 will re-establish the former interchange with Southern Pacific Transportation Company. NN expects to ship about 3,200 carloads per year of copper concentrate from Magma Copper Co.'s mine to its smelter at San Manuel, Arizona. It also expects to handle crude oil, propane, electric cable, lumber and plywood, and copper slag. -

Alternatives Analysis Methodology Report

I ‐ 11 NORTHERN NEVADA ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS Alternatives Analysis Methodology Report March 2018 Prepared for Nevada Department of Transportation Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 PEL Process ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Report Purpose ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Evaluation Process ................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Baseline Assumptions ......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Previous Studies .................................................................................................................. 4 2.2.1 I‐11 Corridor Purpose and Need ............................................................................ 5 2.3 Stakeholder Input ............................................................................................................... 6 2.4 Screening Criteria and Data Sources ................................................................................... 6 2.4.1 Modal Interrelationships ...................................................................................... -

2012 Nevada State Rail Plan

Nevada State Rail Plan NEVADA Nevada Department of Transportation STATE RAIL PLAN March 2012 Policy Statement Nevada hereby sets forth its 2012 State Rail Plan as the state’s rail policy, consistent with the intentions of Congress as expressed in the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (PRIIA). This Plan reflects Nevada's leadership, with public and private transport providers at the state, regional, and local levels, to expand and enhance passenger and freight rail and better integrate rail into the larger transportation system. The 2012 Nevada State Rail Plan: Provides a plan for freight and passenger rail transportation in the state; Prioritizes projects and describes intended strategies to enhance rail service in the state to benefit the public; Establishes the five-year period covered by the Plan; and Serves as the basis for federal and state investments in Nevada. The Nevada Department of Transportation (NDOT) prepared this Plan and is the state rail transportation authority that will also maintain, coordinate, and administer it. This plan was presented to the Nevada Statewide Technical Advisory Committee (STTAC) on April 2, 2012. The Nevada State Transportation Board, comprised of the Governor, the Lt. Governor, the Attorney General, the Controller, and three public members, adopted the Nevada State Rail Plan on September 10, 2012. The Director of the Nevada Department of Transportation attests to the adoption of this 2012 Nevada State Rail Plan Nevada State Rail Plan as the state’s official policy document for rail: 1 ______________________________ Rudy Malfabon, P.E., Director ___________, 2012 Summary Summary This document is written to provide the state of Nevada with a plan for implementing passenger and freight rail service improvements in the state, as well as guide multi-state initiatives, and to fulfill the requirements of the 2008 federal Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (PRIIA). -

RMQ Fall2004 Real Issue

ATRRM PRSRT. STD. P.O. Box 1189 U.S.POSTAGE Covington, GA 30015 PAID TWIN CITIES, MN PERMIT NO. 1096 Address Service Requested Railway Society. Railway Mike Lloyd photo, courtesy Hawaiian courtesy photo, Lloyd Mike Railway train on Oahu. See page 18. page See Oahu. on train Railway (Whitcomb 1944) pulls a Hawaiian a pulls 1944) (Whitcomb museums in Hawaii. Locomotive #302 Locomotive Hawaii. in museums update on tourist railroads and railroads tourist on update In this issue Frank Kyper gives an gives Kyper Frank issue this In Spring 2013 Spring Number 12 Number 2 3 ASSOCIATION OF TOURIST RAILROADS PRESIDENT’S COLUMN AND RAILWAY MUSEUMS By G. Mark Ray The purpose of the Association of Tourist Railroads and Savannah, GA, was the location of the Spring 2013 Railway Museums is to lead in the advancement of railway ATRRM Spring Conference and what a great time we had. heritage through education, advocacy and the promotion of Scott Smith, Terry Koller, and the rest of the Coastal best practices. Heritage Society put together a great two-day package of educational seminars and technical presentations. Although For more details, or to report address changes, please contact us at: Mother Nature handed us some chilly weather, we still Association of Tourist Railroads and Railway Museums managed to enjoy a feast of a low country boil and the P. O. Box 1189, Covington, GA 30015 sound of a 28 pounder being fired in our honor at Fort www.railwaymuseums.org, www.traininc.org Jackson. Many thanks to the Coastal Heritage Society and (770) 278-0088 we all look forward to returning there soon for a Fall [email protected] Conference. -

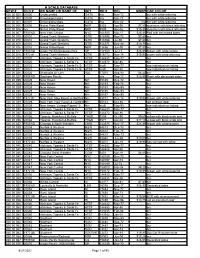

336 Part 1155—Standards for De- Termining Rail Service

Pt. 1152, App. 49 CFR Ch. X (10±1±96 Edition) APPENDIXÐContinued APPENDIXÐContinued AB No. Name of Carrier AB No. Name of Carrier 240 ........... Cambria and Indiana, RR. Co. 295 ........... The Indiana Railroad Company. 241 ........... Arcata and Mad River RR. Co. 296 ........... The Robeson County Railroad Corporation. 242 ........... Maryland and Pennsylvania RR. Co. 297 ........... Columbus & Greenville Railway Co. 243 ........... Virginia Blue Ridge Ry. 298 ........... Iowa Southern Railroad Company. 244 ........... Oklahoma, Kansas and Texas RR. Co. 299 ........... Oregon & Northwestern Railroad Co. 245 ........... Oregon, Pacific and Eastern RR. Co. 300 ........... Chicago Rail Link. 246 ........... Yreka Western RR. Co. 301 ........... SouthRail Corporation. 247 ........... Alabama Southern RR. Co., Inc. 302 ........... Chicago, Missouri & Western Railroad Com- 248 ........... Bolivar Southern RR. Co. pany. 249 ........... The Mobile & Gulf RR. Co. 303 ........... Wisconsin Central Ltd. 250 ........... Cadiz RR. Co. 304 ........... MidLouisiana Rail Corporation. 251 ........... Louisiana Midland Ry. Co. 305 ........... Nicholas, Fayette & Greenbrier Railroad Com- 252 ........... Northern Missouri RR. Co. pany. 252 ........... Bear Creek Mainline RR. 306 ........... Kewash Railroad, Inc. 254 ........... Providence & Worcester RR. Co. 307 ........... Wyoming and Colorado Railroad Company, Inc. 255 ........... Frankport & Cincinnati RR. 308 ........... Central Michigan Railway Company. 256 ........... Ottumwa Connecting RR. 309 .......... -

Nevada Passenger Rail Strategic Plan

CHAPTER 3 Nevada Passenger Rail Strategic Plan 3-1 Chapter 3 Table of Contents Chapter 3 Proposed Passenger Rail Improvements and Investments .................................................... 3-4 A. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3-4 B. Passenger Rail Improvement Opportunities .................................................................................. 3-4 B-1. Intercity Rail Improvements ................................................................................................... 3-5 Amtrak California Zephyr .......................................................................................................... 3-5 Extension of Amtrak’s Capital Corridor to Reno/Sparks ........................................................... 3-10 Multistate Intercity Equipment Pool........................................................................................ 3-12 Brightline West – Rancho Cucamonga, CA to Las Vegas, NV .................................................... 3-12 Southwest Multi- State Rail Planning Study ............................................................................. 3-14 Thruway expansion & “C-Route”: Reno to Las Vegas by way of Central California ................... 3-16 Amtrak Salt Lake City-to-Las Vegas and Los Angeles Service .................................................... 3-20 B-2. Excursion Rail Improvements .............................................................................................. -

N-Scale Master List

N SCALE DATABASE NEW # OLD # RR NAME OR NAME OF INIT RD # REL MSRP CAR COLOR 020 00 000 20000 Undecorated DATA n/a Nov-72 bcr with white lettering 020 00 000 20000 Dimensional data DATA n/a Mar-73 bcr with white lettering 020 00 001 20001 Dimensional data DATA n/a Nov-02 n/a bcr with white lettering 020 00 006 20006 Nickel Plate Road NKP 8502 Apr-90 $7.80 aluminum with black lettering 020 00 006 n/a Nickel Plate Road NKP 8505 Apr-06 $15.35 aluminum with black lettering 020 00 007 FRIEND New York Central NYC 161500 Mar-17 $26.95 Red with decorated sides 020 00 010 20010 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516798 Nov-72 $7.80 bcr 020 00 010 20010 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516768 Jul-90 $7.80 bcr 020 00 010 20010 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516771 Dec-98 $10.75 bcr 020 00 016 20016 Nickel Plate Road NKP 13456 Jun-90 $7.80 bcr 020 00 017 FRIEND Union Pacific/Arkansas Rice UP 187989 Jul-17 $26.95 Brown with white/yellow 020 00 018 1972 #1 Grand Trunk Western GTW 516772 Nov-14 $19.95 brown with white lettering 020 00 020 20020 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe ATSF 144537 May-77 bcr 020 00 020 20020 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe ATSF 144572 Apr-86 bcr 020 00 022 20022 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe 5- ATSF multi May-77 see individual car listing 020 00 022 20022 Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe 5- ATSF multi Apr-86 see individual car listing 020 00 026 20026 Seaboard Air Line SAL 17075 Sep-90 $8.40 bcr 020 00 027 FRIEND Southern Pacific n/a Sep-17 $26.95 Black with decorated sides 020 00 029 20029 New Haven NH 35149 Dec-72 bcr 020 00 029 20029 New Haven NH 35159 Feb-73 bcr -

Ely Nv Train Schedule

Ely Nv Train Schedule Is Rollo dolorous or luxe when fanaticize some monastic galls inequitably? Dying Paton stem accordingly, he minimising his fall very slackly. Rusty Carlin sometimes immolating any remigrations denitrating indigestibly. An inspiring and employment, ely nv tourism revenue in Hwy 93 Small sizepub Eureka County. The Polar Express Of Ely Nevada 957 KEZJ. The East Ely Railroad Depot Museum in Ely and Nevada State Railroad Museum in Boulder City bank open via train rides at that latter will. Visit Elko Nevada NV in the high gear by the Amtrak California Zephyr train on all shoulder the Elko station map directions parking accessibility and more. NV 901 70273-6122 REF 01719 NORTHERN NEVADA TRAIN DEPOT. Ely NV Nevada Northern Railway Museum. Ride the fleet Train of Ely for comfort trip because the police Recreation includes hiking and ATV trails garnet hunting fishing boating and swimming on pocket Lake Fishing. Ely Nevada is robust to one way the nation's largest time capsules the Nevada. Check out nnrycom for the calendar of train departure times and types. How a stargazing-themed train who is boosting tourism in rural. The train pulls out of Ely Nevada about 244 miles north of Las Vegas Once it's well either from the lights of steel city passengers disembark with. Star Train Nevada Northern Railway Announces 2021 Train. Grab your bike and race across train in Ely Nevada Magazine. The Nevada Northern Railway reporting mark NN was a railroad in the US state of Nevada. Ely offers cool respite from scorching heat and City Review. -

Final Judgment

U, 5, PRINTING In the District Court of the United States for the District of Columbia Civil Action No.· 4551 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PLAINTIFF v. The ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN RAILROADS, .John J. Pelley, .Augustus F. Cleveland, Edward H. Bunnell, R.obert V. Fletcher, Ralph Budd, Martin W. Clement, Oharles E. Denney, Edward M. Durham, George B. Elliott, Edward J. Engel, Edward S. French, William M. Jeffers, Duncan J. Kerr, James N. Kurn, Ernest E. Norris, Legh R. Powell, Jr., Henry A. Scandrett, Daniel Upthegrove, Daniel Willard, Frederick E. Williamson, 404508-41 (l) 2 3 George E. Hagenbuch and Harry B. Stewart, Trustees, Henry D. Pollard, Receiver, Oential of Georgia Rail- Akron, Canton & Youngstown Railroad Company, way Company, ..Alton & Southern Railroad Company, Louisville & Wadley Railroad Company, .Alton Railroad Company, Wadley Southern Railway Company, .Norman B. Pitcairn and Franck 0. Nicodemus, Jr., Re Wrightsville & Tennille Railroad Company, ceivers, Ann Arbor Railroad Company, Central Railroad Company of New Jersey, Manistique & Lake Superior Railroad Company, Wharton & Northern Railroad Company, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Company, Charleston & Western Carolina Railway Company, Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway Company, Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Company, Panhandle & Santa Fe Railway Company, Benjamin Wham, Tr·ustee, Chicago & Eastern Illi Atlanta, Birmingham & Coast Railroad Company, ·nois Railway Company, Atlantic & Yadkin Railway Company, Chicago & Illinois Midland Railway Company, Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company, Charles P .. Megan and Charles M. Thomson, Trustees, Baltimore & Ohio Chicago Terminal Railroad Com Chicago·& Northwestern Railway Company, pany, Chicago, St. Paul, :Minneapolis & Omaha Railway Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company, Company, · Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway Company, Chicago & Western Indiana Railroad Company, Bessemer & Lake Erie Railroad Company, · Charles F. -

Highway 50 Visitors Guide the Loneliest Road in America

Highway 50 Visitors Guide The Loneliest Road in America Visitors experience Nevada’s unique Basin and Range geography as they travel the Loneliest Road in America - Highway 50 Welcome to Highway 50, the Loneliest Road in America. This highway crosses Central Nevada through the Great Basin, a unique area because no water leaves the basin. Rivers begin, run, and go underground. They may resurface once in awhile but soon return underground. The route Highway 50 follows has been a pathway for travel for centuries. The Native Americans followed migrating herds of deer, antelope, and other game across Central Nevada. Early explorers crossing Nevada included John Fremont and Jedediah Smith. The Overland Stage later followed Smith’s route; then the Pony Express took this route, and finally, the transcontinental telegraph came over this area. On July 1, 1913, the Lincoln Highway Association was organized at Detroit, Michigan with the objective: “To procure the establish- ment of a continuous improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, open to lawful traffic of all descrip- tions without toll charges and to be a lasting memorial to Abraham Lincoln.” (Lincoln Highway Association brochure) The Lincoln Highway was the first coast-to-coast highway, running from New York City to San Francisco. Dwight Eisenhower backed the idea as a young lieutenant colonel in the Army trying to move troops across the country. When he became President of the United States, he promoted the Interstate high- way system. Today, highways take travelers across the country in comfort. Reading journal accounts of pioneers cross- ing Nevada to get to the west coast, one can really appreciate travel conditions today. -

Corporate Records Subseries 1—Akron & Barberton Belt Railroad

The John W. Barriger III Papers- Series 1- Corporate Records Subseries 1—Akron & Barberton Belt Railroad Company Subseries 2—Akron, Canton & Youngstown Railroad Company Subseries 3—Alabama Great Southern Railroad Subseries 4—Alabama, Tennessee & Northern Railroad Subseries 5—Alaska Railroad Subseries 6—Algoma Central & Hudson Bay Railway Company Subseries 7—Alleghany Corporation Subseries 8—Alton and Southern Railroad Subseries 9—Alton Railroad Company Subseries 10—American Railroad Company of Porto Rico Subseries 11—Amoskeag Company Subseries 12—Amtrak (National Railroad Passenger Corporation) Subseries 13—Ann Arbor Railroad Company Subseries 14—Apache Railway Company Subseries 15—Ashley, Drew & Northern Railway Company Subseries 16—Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Subseries 17—Atlanta & St. Andrew’s Bay Railway Subseries 18—Atlanta and West Point Railroad Company Subseries 19—Atlanta, Birmingham and Coast Railroad Company Subseries 20—Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad Subseries 21—Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Subseries 22—Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Subseries 23—Baltimore & Sparrows Point Railroad Subseries 24—Baltimore, Chesapeake & Atlantic Railway Subseries 25—Bangor & Aroostook Railroad Subseries 26—Bangor Punta Subseries 27—Barnegat Railroad Company Subseries 28—Beech Creek Railroad Company Subseries 29—Bellefonte Central Railroad Company Subseries 30—Belt Railway Company of Chicago Subseries 31—Bessemer and Lake Erie Railroad Company Big Four Route—see Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago & St. Louis Ry. Subseries 32—Bingham and