In Construction in Construction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

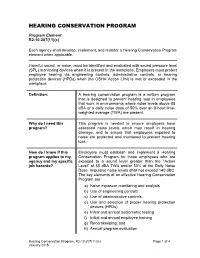

Hearing Conservation Program

HEARING CONSERVATION PROGRAM Program Element R2-10-207(11)(c) Each agency shall develop, implement, and monitor a Hearing Conservation Program element when applicable. Harmful sound, or noise, must be identified and evaluated with sound pressure level (SPL) monitoring devices when it is present in the workplace. Employers must protect employee hearing via engineering controls, administrative controls, or hearing protection devices (HPDs) when the OSHA Action Limit is met or exceeded in the workplace. Definition: A hearing conservation program is a written program that is designed to prevent hearing loss in employees that work in environments where noise levels above 85 dBA or a daily noise dose of 50% over an 8-hour time- weighted average (TWA) are present. Why do I need this This program is needed to ensure employers have program? assessed noise levels which may result in hearing damage, and to ensure that employees exposed to noise are protected and monitored to prevent hearing loss. How do I know if this Employers must establish and implement a Hearing program applies to my Conservation Program for those employees who are agency and my specific exposed to a sound level greater than the “Action job hazards? Level” of 85 dBA TWA and/or 50% of the Daily Noise Dose. Impulsive noise levels shall not exceed 140 dBC. The key elements of an effective Hearing Conservation Program are: a) Noise exposure monitoring and analysis b) Use of engineering controls c) Use of administrative controls d) Use and selection of proper hearing protection devices (HPDs) e) Initial and annual audiometric testing f) Initial and annual employee training g) Recordkeeping; and h) Annual program evaluation Hearing Conservation Program, R2-10-207(11)(c) Page 1 of 4 January 2015 What are the minimum There are five OSHA required Hearing Conservation required elements and/ Program elements: or best practices for a Hearing Conservation 1. -

Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition

PRINT Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition John R. Schermerhorn, Jr. Ohio University James G. Hunt Texas Tech University Richard N. Osborn Wayne State University ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR 7TH edition Copyright 2002 © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-471-22819-2 (ebook) 0-471-42063-8 (print version) Brief Contents SECTION ONE 1 Management Challenges of High Performance SECTION FOUR 171 Organizations 81 Organizational Behavior Today 3 Illustrative Case: Creating a High Performance Power 173 Learning About Organizational Behavior 5 Organization 84 Empowerment 181 Organizations as Work Settings 7 Groups in Organizations 87 Organizational Politics 183 Organizational Behavior and Management 9 Stages of Group Development 90 Political Action and the Manager 186 Ethics and Organizational Behavior 12 Input Foundations of Group Effectiveness 92 The Nature of Communication 190 Workforce Diversity 15 Group and Intergroup Dynamics 95 Essentials of Interpersonal Communication Demographic Differences 17 Decision Making in Groups 96 192 Aptitude and Ability 18 High Performance Teams 100 Communication Barriers 195 Personality 19 Team Building 103 Organizational Communication 197 Personality Traits and Classifications 21 Improving Team Processes 105 -

422 PART 227—OCCUPATIONAL NOISE EXPOSURE Subpart A—General

Pt. 227 49 CFR Ch. II (10–1–20 Edition) by the BLS. The wage component is weight- 227.15 Information collection. ed by 40% and the equipment component by 60%. Subpart B—Occupational Noise Exposure 2. For the wage component, the average of for Railroad Operating Employees the data from Form A—STB Wage Statistics for Group No. 300 (Maintenance of Way and 227.101 Scope and applicability. Structures) and Group No. 400 (Maintenance 227.103 Noise monitoring program. of Equipment and Stores) employees is used. 227.105 Protection of employees. 3. For the equipment component, 227.107 Hearing conservation program. LABSTAT Series Report, Producer Price 227.109 Audiometric testing program. Index (PPI) Series WPU 144 for Railroad 227.111 Audiometric test requirements. Equipment is used. 227.113 Noise operational controls. 4. In the month of October, second-quarter 227.115 Hearing protectors. wage data are obtained from the STB. For 227.117 Hearing protector attenuation. equipment costs, the corresponding BLS rail- 227.119 Training program. road equipment indices for the second quar- 227.121 Recordkeeping. ter are obtained. As the equipment index is APPENDIX A TO PART 227—NOISE EXPOSURE reported monthly rather than quarterly, the COMPUTATION average for the months of April, May and APPENDIX B TO PART 227—METHODS FOR ESTI- June is used for the threshold calculation. 5. The wage data are reported in terms of MATING THE ADEQUACY OF HEARING PRO- dollars earned per hour, while the equipment TECTOR ATTENUATION cost data are indexed to a base year of 1982. APPENDIX C TO PART 227—AUDIOMETRIC BASE- 6. -

Tinnitus Characteristics at High-And Low-Risk Occupations from Occupational Noise Exposure Standpoint

PERSPECTIVE DOI: 10.5935/0946-5448.20210016 International Tinnitus Journal. 2021;25(1):87-93 Tinnitus characteristics at high-and low-risk occupations from occupational noise exposure standpoint Mehdi Asghari ABSTRACT Introduction: The aim of the present study was to compare tinnitus characteristics in high- and low-risk occupations from the occupational noise exposure standpoint, considering demographic data, hearing loss and concomitant diseases. Methods: Demographic data, characteristics of tinnitus, hearing and concomitant diseases were recorded in the questionnaires. Their pure tone air conduction thresholds were determined using a double-channel diagnostic Audiometer and the Bone Conduction was assessed using a B-71 bone vibrator. Results: Totally, 6.3% subjects (6.8% high-risk group and 5.6% low-risk group) had subjective tinnitus, mainly as whistling sound. In the high-risk group, tinnitus was mainly left-sided (41.18%) and hearing loss was mild. Bilateral tinnitus (52.63%) and slight hearing loss were observed predominantly in the low-risk group. Conclusions: The study showed higher incidence of tinnitus in high-risk professions regarding with occupational noise exposure. Keywords: Tinnitus; Loudness; Hearing loss; Noise exposure; High-risk occupations. 1Department of Medical Sciences, Arak University, Iran *Send correspondence to: Mehdi Asghari Department of Medical Sciences, Arak University, Iran. E-mail: [email protected], Phone: +81302040753 Paper submitted on February 07, 2021; and Accepted on April 18, 2021 87 International Tinnitus Journal, Vol. 25, No 1 (2021) www.tinnitusjournal.com INTRODUCTION 20 to 60 years referred to XXX Occupational Medicine Centers in 2018, Arak, Iran. Inclusion criteria included Tinnitus is a sound sensation in the ears or head in the age ≥18, at least a fifth grade education, wok experience absence of an external auditory or electrical source. -

Preventing Hazardous Noise and Hearing Loss

Preventing Hazardous Noise and Hearing Loss during Project Design and Operation Prevention through Design (PtD) Prevention through Design (PtD) Why is PtD Needed? Description of can be defined as designing out Integrating PtD concepts into busi- Exposure or eliminating safety and health ness processes helps reduce injury and hazards associated with processes, Prolonged exposure to high noise levels structures, equipment, tools, or illness in the workplace, as well as costs can cause hearing loss and tinnitus. work organization. The National associated with injuries. PtD lays the Other health effects include headaches, Institute for Occupational Safety foundation for a sustainable culture of fatigue, stress, and cardiovascular and Health (NIOSH) launched a safety with lower workers’ compensation problems [Yueh et al. 2003]. High noise PtD initiative in 2007. The mission expenses, fewer retrofits, and improved levels can also cause workers to be dis- tracted and interfere with communica- is to reduce or prevent occupational productivity. When PtD concepts are in- injuries, illnesses, and fatalities by tion and warning signals. If workers do troduced early in the design process, re- considering hazard prevention in not hear warning signals, they may not the design, re-design, and retrofit of sources can be allocated more efficiently. take precautions to prevent hazards or new and existing workplaces, tools, injuries [NIOSH 1996, 1998; Yoon et al. equipment, and work processes Summary 2015; Cantley et al. 2015]. [NIOSH 2008a,b]. Exposure to high noise levels in the workplace can cause hearing loss and Workers at Risk Contents affect worker productivity and compen- An estimated twenty-two million work- ▶ Why is PtD Needed sation costs. -

FAA/OSHA Aviation Safety and Health Team, First Report

FAA / OSHA Aviation Safety and Health Team First Report Application of OSHA’s Requirements to Employees on Aircraft in Operation December 2000 FAA/OSHA Aviation Safety and Health Team (First Report) Table of Contents Executive Summary. ..................................................................................................ii Introduction. .............................................................................................................. iv Discussion....................................................................................................................1 Issue 1 - Recordkeeping. .........................................................................................2 Issue 2 - Bloodborne pathogens. .............................................................................6 Issue 3 - Noise. ......................................................................................................11 Issue 4 - Sanitation. ...............................................................................................14 Issue 5 - Hazard communication. ..........................................................................18 Issue 6 - Anti-discrimination. ................................................................................22 Issue 7 - Access to employee exposure/medical records.......................................25 Matters for Further Consideration. .......................................................................27 Appendices. A. FAA/OSHA Memorandum of Understanding, August 7, 2000. ...................29 -

MARCH, 1970 Ilini’Tj-Ljiril’ Jleu/S Qtie U\Lmgty-Cafmes^

MARCH, 1970 Ilini’tj-lJiriL’ Jleu/s QTie u\lmGty-cAfmes^. umn March, 1970 Speaking of potential, have you •w heard about Turi Wideroe? A most at As I sit here about to start my tractive young lady Airline Captain Monthly Message to you, the sun is from Oslo, Norway. Hope she will shining on glistening white snow and become a Ninety-Nine and let us all the temperature is zero. There isn’t a in on her secret to success. I know you all join me in wishing her well MARCH, 1970 cloud in the sky and I’m thinking in her new assignment. We’re all so ahead a couple of hours and the fact proud of our feminine accomplish THE NINETY-NINES, Inc. that I will be flying today and this ments in the field of aviation. After all Will Rogers World Airport brings to mind how very hard a long this is what our Ninety-Nines’ Museum International Headquarters win’er is on people. I guess people just Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73159 is made of. aren’t like bears content with hiberna Sectional Meeting time is here and Headquarters Secretary tion. It seems easy to let little things “Project Awareness” will be our LORETTA GRAGG begin to bother you when you feel theme. You know the best way to learn couped up and winter is that kind of a subject is to teach it. So get involved Editor thing at times. With Spring in the air in this Seminar on Ninety-Nineman- HAZEL McKENDRICK let’s all get the cob-webs out of our ship. -

Occupational Noise Exposure Noise, Or Unwanted Sound, Is One of the Most Pervasive Occupational Health Problems

Occupational Noise Exposure Noise, or unwanted sound, is one of the most pervasive occupational health problems. It is a by-product of many industrial processes. Sound consists of pressure changes in a medium (usually air), caused by vibration or turbulence. These pressure changes produce waves emanating away from the turbulent or vibrating source. Exposure too high levels of noise causes hearing loss and may cause other harmful health effects as well. The extent of damage depends primarily on the intensity of the noise and the duration of the exposure. Noise-induced hearing loss can be temporary or permanent. Temporary hearing loss results from short-term exposures to noise, with normal hearing returning after a period of rest. Generally, prolonged exposure to high noise levels over a period of time gradually causes permanent damage. OSHA's hearing conservation program is designed to protect workers with significant occupational noise exposures from suffering material hearing impairment even if they are subject to such noise exposures over their entire working lifetimes. Monitoring The hearing conservation program requires employers to monitor noise exposure levels in a manner that will accurately identify employees who are exposed to noise at or above 85 decibels (dB) averaged over 8 working hours, or an 8-hour time-weighted average (TWA.) That is, employers must monitor all employees whose noise exposure is equivalent to or greater than a noise exposure received in 8 hours where the noise level is constantly 85 dB. The exposure measurement must include all continuous, intermittent, and impulsive noise within an 80 dB to 130-dB range and must be taken during a typical work situation. -

Volume 28, Issue 13 Virginia Register of Regulations February 27, 2012 1039 PUBLICATION SCHEDULE and DEADLINES

VOL. 28 ISS. 13 PUBLISHED EVERY OTHER WEEK BY THE VIRGINIA CODE COMMISSION FEBRUARY 27, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Register Information Page .........................................................................................................................................1039 Publication Schedule and Deadlines.......................................................................................................................1040 Petitions for Rulemaking ............................................................................................................................................1041 Notices of Intended Regulatory Action .................................................................................................................1042 Regulations .......................................................................................................................................................................1043 8VAC115-30. Richard Bland College Weapons on Campus Regulation (Final) ..................................................................1043 10VAC5-40. Credit Unions (Final)........................................................................................................................................1043 11VAC10-20. Regulations Pertaining to Horse Racing with Pari-Mutuel Wagering (Final) ................................................1045 11VAC10-50. Racing Officials (Final)..................................................................................................................................1052 -

Noise Induced Hearing Loss: an Occupational Medicine Perspective Emily Z

Noise induced hearing loss: An occupational medicine perspective Emily Z. Stucken MD Michigan Ear Institute Robert S. Hong MD, PhD Michigan Ear Institute Corresponding author: Robert S. Hong MD, PhD Michigan Ear Institute 30055 Northwestern Highway, Suite #101 Farmington Hills, MI 48334 Phone (248) 865-4444 Abstract Purpose of review: Up to 30 million workers in the United States are exposed to potentially detrimental levels of noise. While reliable medications for minimizing or reversing noise induced hearing loss (NIHL) are not currently available, NIHL is entirely preventable. The purpose of this article is to review the epidemiology and pathophysiology of occupational NIHL. We will focus on at-risk populations and discuss prevention programs. Current prevention programs focus on reduction of inner ear damage by minimizing environmental noise production and through the use of personal hearing protective devices. Recent findings: Noise induced hearing loss is the result of a complex interaction between environmental factors and patient factors, both genetic and acquired. The effects of noise exposure are specific to an individual. Trials are currently underway evaluating the role of antioxidants in protection from, and even reversal of, NIHL. Summary: Occupational NIHL is the most prevalent occupational disease in the United States. Occupational noise exposures may contribute to temporary or permanent threshold shifts, though even temporary threshold shifts may predispose an individual to eventual permanent hearing loss. Noise prevention programs are paramount in reducing hearing loss as a result of occupational exposures. Key words: occupational noise induced hearing loss, occupational noise exposure, hearing protection programs Introduction Hearing loss is the most widespread disability in Westernized society. -

Reducing the Risks from Occupational Noise

Cover Noise Report 6/10/05 15:05 Pagina 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 1 EN European Agency for Safety and Health at Work TE-68-05-535-EN-C EUROPEAN WEEK FOR SAFETY AND HEALTH AT WORK EN 1 In order to improve the working environment, ISSN 1681-0155 as regards the protection of the safety and health 2. of workers as provided for in the Treaty and successive Community strategies and action programmes concerning health and safety at Reducing the risks from occupational noise occupational Reducing the risks from the workplace, the aim of the Agency shall be to provide the Community bodies, the Member States, the social partners and those involved in the field with the technical, scientific and economic information of use in the field of safety and health at work. 3. 1. http://osha.eu.int Reducing the risks from occupational noise European Agency for Safety and Health at Work Gran Vía 33, E-48009 Bilbao Tel.: +34 944 794 360 Fax: +34 944 794 383 E-mail: [email protected] EUROPEAN WEEK Price (excluding VAT) in Luxembourg: EUR 15 ISBN 92-9191-167-4 European Agency for Safety and Health at Work Agency for Safety European and Health at European Agency for Safety and Health at Work Compuesta Noise Report 6/10/05 15:07 Página 1 European Agency for Safety and Health at Work EUROPEAN WEEK FOR SAFETY AND HEALTH AT WORK EN 1 ISSN 1681-0155 2. 3. 1. Reducing the risks from occupational noise European Agency for Safety and Health at Work Noise Report 6/10/05 15:07 Página 2 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. -

Workforce Development and Unemployment Insurance Provisions

ALABAMA ALASKA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO CONNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY LOUISIANA Implementation of the MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNE- SOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NE- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: VADA NEW HAMPSHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLA- HOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA PUERTO RICO RHODE ISLAND SOUTH CAROLINA SOUTH DAKOTA TENNESSEE TEXAS UTAH VERMONT VIRGINIA WASHINGTON WEST Workforce Development and VIRGINIA WISCONSIN WYOMING ALABAMA ALASKA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO CON- Unemployment Insurance ProvisionsNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY LOUISIANA MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NEVADA NEW HAMP- SHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH FINAL REPORT CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA PUERTO RICO RHODE ISLAND SOUTH CAR- OLINA SOUTH DAKOTA TENNESSEE TEXAS UTAH VER- October 2012 MONT VIRGINIA WASHINGTON WEST VIRGINIA WISCON- SIN WYOMING ALABAMA ALASKA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO CONNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KEN- TUCKY LOUISIANA MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NEVADA NEW HAMPSHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA