Noise Induced Hearing Loss: an Occupational Medicine Perspective Emily Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing Conservation Program

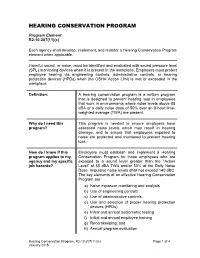

HEARING CONSERVATION PROGRAM Program Element R2-10-207(11)(c) Each agency shall develop, implement, and monitor a Hearing Conservation Program element when applicable. Harmful sound, or noise, must be identified and evaluated with sound pressure level (SPL) monitoring devices when it is present in the workplace. Employers must protect employee hearing via engineering controls, administrative controls, or hearing protection devices (HPDs) when the OSHA Action Limit is met or exceeded in the workplace. Definition: A hearing conservation program is a written program that is designed to prevent hearing loss in employees that work in environments where noise levels above 85 dBA or a daily noise dose of 50% over an 8-hour time- weighted average (TWA) are present. Why do I need this This program is needed to ensure employers have program? assessed noise levels which may result in hearing damage, and to ensure that employees exposed to noise are protected and monitored to prevent hearing loss. How do I know if this Employers must establish and implement a Hearing program applies to my Conservation Program for those employees who are agency and my specific exposed to a sound level greater than the “Action job hazards? Level” of 85 dBA TWA and/or 50% of the Daily Noise Dose. Impulsive noise levels shall not exceed 140 dBC. The key elements of an effective Hearing Conservation Program are: a) Noise exposure monitoring and analysis b) Use of engineering controls c) Use of administrative controls d) Use and selection of proper hearing protection devices (HPDs) e) Initial and annual audiometric testing f) Initial and annual employee training g) Recordkeeping; and h) Annual program evaluation Hearing Conservation Program, R2-10-207(11)(c) Page 1 of 4 January 2015 What are the minimum There are five OSHA required Hearing Conservation required elements and/ Program elements: or best practices for a Hearing Conservation 1. -

NOISE and MILITARY SERVICE Implications for Hearing Loss and Tinnitus

NOISE AND MILITARY SERVICE Implications for Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Committee on Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Associated with Military Service from World War II to the Present Medical Follow-up Agency Larry E. Humes, Lois M. Joellenbeck, and Jane S. Durch, Editors THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, DC www.nap.edu THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS • 500 Fifth Street, N.W. • Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Insti- tute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This study was supported by Contract No. V101(93)P-1637 #29 between the Na- tional Academy of Sciences and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Any opinions, find- ings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the organizations or agencies that provided support for this project. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Noise and military service : implications for hearing loss and tinnitus / Committee on Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Associated with Military Service from World War II to the Present, Medical Follow- up Agency ; Larry E. Humes, Lois M. Joellenbeck, and Jane S. Durch, editors. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-309-09949-8 — ISBN 0-309-65307-X 1. Deafness—Etiology. -

Monitoring of Sound Pressure Level

1. INTRODUCTION Noise is one of the main environmental problems of modern life and it is inseparable from human activities, urban and technological growth. National and international standards provide for a minimum of acoustic comfort for coexistence between man and industrial development. That's why a study of noise emission and environmental noise at the PALAGUA - CAIPAL Field was carried out; samples of measurements were taken in specific (punctual) manner to meet the sound pressure level (SPL) with a duration of five minutes per sample/measurement for noise measurements and 15 minutes for ambient or environmental noise in each direction: (north, east, south, west and vertical). The result of these measurements was compared with the maximum permissible noise emission and environmental noise standards stated in Resolution 627 of 2006 Ministry of Environment, Housing, and Territorial Development (MAVDT) and thus it was verified that they comply with environmental regulations in the PALAGUA - CAIPAL Field. 1 INFORME DE LABORATORIO 0860-09-ECO. NIVELES DE PRESIÓN SONORA EN EL AREA DE PRODUCCION CAMPO PALAGUA - CAIPAL PUERTO BOYACA, BOYACA. NOVIEMBRE DE 2009. 2. OBJECTIVES • To evaluate the emission of noise and environmental noise encountered in the PALAGUA - CAIPAL Gas Field area, located in the municipality of Puerto Boyacá, Boyacá. • To compare the obtained sound pressure levels at points monitored, with the permissible limits of resolution 627 of the Ministry of Environment, SECTOR C: RESTRICTED INTERMEDIATE NOISE, which allows a maximum of 75 dB in the daytime (7:01 to 21:00) and 70 dB in the night shift (21:01 to 7: 00 hours) 2 INFORME DE LABORATORIO 0860-09-ECO. -

The Psychophysiological Implications of Soundscape: a Systematic Review of Empirical Literature and a Research Agenda

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review The Psychophysiological Implications of Soundscape: A Systematic Review of Empirical Literature and a Research Agenda Mercede Erfanian * , Andrew J. Mitchell , Jian Kang * and Francesco Aletta UCL Institute for Environmental Design and Engineering, The Bartlett, University College London (UCL), Central House, 14 Upper Woburn Place, London WC1H 0NN, UK; [email protected] (A.J.M.); [email protected] (F.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.E.); [email protected] (J.K.); Tel.: +44-(0)20-3108-7338 (J.K.) Received: 16 September 2019; Accepted: 19 September 2019; Published: 21 September 2019 Abstract: The soundscape is defined by the International Standard Organization (ISO) 12913-1 as the human’s perception of the acoustic environment, in context, accompanying physiological and psychological responses. Previous research is synthesized with studies designed to investigate soundscape at the ‘unconscious’ level in an effort to more specifically conceptualize biomarkers of the soundscape. This review aims firstly, to investigate the consistency of methodologies applied for the investigation of physiological aspects of soundscape; secondly, to underline the feasibility of physiological markers as biomarkers of soundscape; and finally, to explore the association between the physiological responses and the well-founded psychological components of the soundscape which are continually advancing. For this review, Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and -

Deafness and Hearing Loss Caroline’S Story

Deafness and Hearing Loss Caroline’s Story Caroline is six years old, A publication of NICHCY with bright brown eyes and, at Disability Fact Sheet #3 June 2010 the moment, no front teeth, like so many other first graders. She also wears a hearing aid in each ear—and has done so since she was three, when she Caroline was immediately Hearing Loss was diagnosed with a moderate fitted with hearing aids. She in Children hearing loss. also began receiving special education and related services Hearing is one of our five For Caroline’s parents, there through the public school senses. Hearing gives us access were many clues along the way. system. Now in the first grade, to sounds in the world around Caroline often didn’t respond she regularly gets speech us—people’s voices, their to her name if her back was therapy and other services, and words, a car horn blown in turned. She didn’t startle at her speech has improved warning or as hello! noises that made other people dramatically. So has her vocabu- jump. She liked the TV on loud. lary and her attentiveness. She When a child has a hearing But it was the preschool she sits in the front row in class, an loss, it is cause for immediate started attending when she was accommodation that helps her attention. That’s because three that first put the clues hear the teacher clearly. She’s language and communication together and suggested to back on track, soaking up new skills develop most rapidly in Caroline’s parents that they information like a sponge, and childhood, especially before the have her hearing checked. -

Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition

PRINT Organizational Behavior Seventh Edition John R. Schermerhorn, Jr. Ohio University James G. Hunt Texas Tech University Richard N. Osborn Wayne State University ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR 7TH edition Copyright 2002 © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data base retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-471-22819-2 (ebook) 0-471-42063-8 (print version) Brief Contents SECTION ONE 1 Management Challenges of High Performance SECTION FOUR 171 Organizations 81 Organizational Behavior Today 3 Illustrative Case: Creating a High Performance Power 173 Learning About Organizational Behavior 5 Organization 84 Empowerment 181 Organizations as Work Settings 7 Groups in Organizations 87 Organizational Politics 183 Organizational Behavior and Management 9 Stages of Group Development 90 Political Action and the Manager 186 Ethics and Organizational Behavior 12 Input Foundations of Group Effectiveness 92 The Nature of Communication 190 Workforce Diversity 15 Group and Intergroup Dynamics 95 Essentials of Interpersonal Communication Demographic Differences 17 Decision Making in Groups 96 192 Aptitude and Ability 18 High Performance Teams 100 Communication Barriers 195 Personality 19 Team Building 103 Organizational Communication 197 Personality Traits and Classifications 21 Improving Team Processes 105 -

Soundscape Mapping in Environmental Noise Management and Urban Planning

This is a repository copy of Soundscape mapping in environmental noise management and urban planning. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/128385/ Version: Published Version Article: Margaritis, E. and Kang, J. orcid.org/0000-0001-8995-5636 (2017) Soundscape mapping in environmental noise management and urban planning. Noise Mapping (4). 1. pp. 87-103. ISSN 2084-879X https://doi.org/10.1515/noise-2017-0007 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Noise Mapp. 2017; 4:87ś103 Research Article Efstathios Margaritis* and Jian Kang Soundscape mapping in environmental noise management and urban planning: case studies in two UK cities https://doi.org/10.1515/noise-2017-0007 tentional design process comparable to landscape and to Received Dec 22, 2017; accepted Dec 28, 2017 introduce the theories of soundscape into the design pro- cess of urban public spaces”. Lately, suggestions of ap- plied soundscape practises were introduced in the Master plan level thanks to the initiative of the local authorities. -

422 PART 227—OCCUPATIONAL NOISE EXPOSURE Subpart A—General

Pt. 227 49 CFR Ch. II (10–1–20 Edition) by the BLS. The wage component is weight- 227.15 Information collection. ed by 40% and the equipment component by 60%. Subpart B—Occupational Noise Exposure 2. For the wage component, the average of for Railroad Operating Employees the data from Form A—STB Wage Statistics for Group No. 300 (Maintenance of Way and 227.101 Scope and applicability. Structures) and Group No. 400 (Maintenance 227.103 Noise monitoring program. of Equipment and Stores) employees is used. 227.105 Protection of employees. 3. For the equipment component, 227.107 Hearing conservation program. LABSTAT Series Report, Producer Price 227.109 Audiometric testing program. Index (PPI) Series WPU 144 for Railroad 227.111 Audiometric test requirements. Equipment is used. 227.113 Noise operational controls. 4. In the month of October, second-quarter 227.115 Hearing protectors. wage data are obtained from the STB. For 227.117 Hearing protector attenuation. equipment costs, the corresponding BLS rail- 227.119 Training program. road equipment indices for the second quar- 227.121 Recordkeeping. ter are obtained. As the equipment index is APPENDIX A TO PART 227—NOISE EXPOSURE reported monthly rather than quarterly, the COMPUTATION average for the months of April, May and APPENDIX B TO PART 227—METHODS FOR ESTI- June is used for the threshold calculation. 5. The wage data are reported in terms of MATING THE ADEQUACY OF HEARING PRO- dollars earned per hour, while the equipment TECTOR ATTENUATION cost data are indexed to a base year of 1982. APPENDIX C TO PART 227—AUDIOMETRIC BASE- 6. -

Hearing Impairment Sheet

Oklahoma State Department of Education Special Education Services • 405-521-3351 • www.ok.gov/sde/special-education FACT HEARING IMPAIRMENT SHEET ■ Definition of Intellectual POSSIBLE CAUSES Disabilities under IDEA • Acquired, meaning that the loss occurred after birth, Hearing impairment means an impairment in hearing, due to illness or injury; or whether permanent or fluctuating, that adversely affects • Congenital, meaning that the hearing loss or deafness a child’s educational performance. 34 CFR 300.8(c)(5) was present at birth The most common cause of acquired hearing loss is TYPES exposure to noise (Merck Manual’s Online Medical Conductive hearing losses are caused by diseases or Library, 2007). Other causes can include: obstructions in the outer or middle ear (the pathways • Build up of fluid behind the eardrum for sound to reach the inner ear). Conductive hearing • Ear infections (known as otitis media) losses usually affect all frequencies of hearing evenly • Childhood diseases, such as mumps, measles, or and do not result in severe losses. A person with a con- chicken pox; and ductive hearing loss usually is able to use a hearing aid • Head trauma well or can be helped medically or surgically. Congenital causes of hearing loss and Sensorineural hearing losses result from damage to the deafness include: delicate sensory hair cells of the inner ear or the nerves • A family history of hearing loss or deafness that supply it. These hearing losses can range from • Infections during pregnancy (such as rubella) mild to profound. They often affect the person’s abil- • Complications during pregnancy (such as the Rh ity to hear certain frequencies more than others. -

Tinnitus Characteristics at High-And Low-Risk Occupations from Occupational Noise Exposure Standpoint

PERSPECTIVE DOI: 10.5935/0946-5448.20210016 International Tinnitus Journal. 2021;25(1):87-93 Tinnitus characteristics at high-and low-risk occupations from occupational noise exposure standpoint Mehdi Asghari ABSTRACT Introduction: The aim of the present study was to compare tinnitus characteristics in high- and low-risk occupations from the occupational noise exposure standpoint, considering demographic data, hearing loss and concomitant diseases. Methods: Demographic data, characteristics of tinnitus, hearing and concomitant diseases were recorded in the questionnaires. Their pure tone air conduction thresholds were determined using a double-channel diagnostic Audiometer and the Bone Conduction was assessed using a B-71 bone vibrator. Results: Totally, 6.3% subjects (6.8% high-risk group and 5.6% low-risk group) had subjective tinnitus, mainly as whistling sound. In the high-risk group, tinnitus was mainly left-sided (41.18%) and hearing loss was mild. Bilateral tinnitus (52.63%) and slight hearing loss were observed predominantly in the low-risk group. Conclusions: The study showed higher incidence of tinnitus in high-risk professions regarding with occupational noise exposure. Keywords: Tinnitus; Loudness; Hearing loss; Noise exposure; High-risk occupations. 1Department of Medical Sciences, Arak University, Iran *Send correspondence to: Mehdi Asghari Department of Medical Sciences, Arak University, Iran. E-mail: [email protected], Phone: +81302040753 Paper submitted on February 07, 2021; and Accepted on April 18, 2021 87 International Tinnitus Journal, Vol. 25, No 1 (2021) www.tinnitusjournal.com INTRODUCTION 20 to 60 years referred to XXX Occupational Medicine Centers in 2018, Arak, Iran. Inclusion criteria included Tinnitus is a sound sensation in the ears or head in the age ≥18, at least a fifth grade education, wok experience absence of an external auditory or electrical source. -

5. Noise Pollution

5. Noise pollution 1. Please describe the present situation and development over the last five to ten years in relation to (max. 1,000 words): Within the scope of implementing “Directive 2002/49/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 25 June 2002, relating to the assessment and management of environmental noise”, the proportion of Hamburg’s population subjected to noise emanations from road, railway and air traffic sources as well as industrial, commercial and port facilities has been determined in terms of the noise indicators L den, for noise levels during the day, evening and night, and L night, for noise levels at night. The assessment was calculated on the basis of national provisional computation methods; namely, the “Provisional computation method for environmental noise on roads – VBUS”, the “Provisional computation method for environmental noise on railways – VBUSch”, the “Provisional computation method for environmental noise at airports – VBUF”, the “Provisional computation method for environmental noise from industry and commercial facilities – VBUI”, and the “Provisional computation method for determining the number of individuals exposed to environmental noise – VBEB”. In terms of the industrial, commercial and port sector, in addition to plants located in the port area, only those industrial or commercial zones with one or more plants as per Appendix 1 of the “European Council Directive 96/61/EC of 24 September 1996 concerning integrated pollution prevention and control” are afforded consideration. The period of reference is 2006. Accordingly, the number of individuals affected is as follows: Affected by L den > Affected by L night > 55 dB(A) 45 dB(A) Road traffic 363600 420900 Rail traffic 56200 38900 (L night > 50 dB(A)) Air traffic 43700 5000 (L night > 50 dB(A)) Industry/commercial 4200 10200 /port facilities In line with the requirements of the EU directive, the analyses are updated at least every 5 years, from which commensurate developments regarding issues of concern can be ascertained. -

Tinnitus What Is Tinnitus? Tinnitus Is Defined As the Perception of Sound When No External Sound Is Present

Tinnitus What is tinnitus? Tinnitus is defined as the perception of sound when no external sound is present. The common vernacular is "ringing in the ears"; however, the quality of the tinnitus can range from roaring to hissing and chirping to clicking. Tinnitus can pulsate or be constant. It can be a single tone or multiple tones, and it's amplitude can vary from background noise to an excruciating experience. What causes tinnitus? Tinnitus has a variety of causes. The most common causes include wax in the ear canal, noise trauma or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction. It can also be caused by Meniere's disease, endolymphatic hydrops, allergies, destruction of the middle ear bones, infection, nutritional deficiency, cardiovascular disease, thyroid disorders, certain medications, head injury and cervical disorders. Recently, migraine disorders have also been listed as a culprit. Regardless of the inciting etiology, it has been shown that the it is within the brain that the sound resides, persists, evolves and propagates. Tinnitus may begin with damage to the peripheral auditory system (the cochlea and auditory nerve), but its persistence is a function of the attention that it receives parietal cortex and frontal cortex), the importance that it is given (cingulate cortex, anterior insula) and it maintaining residence in the limbic system (the amygdala, hippocampus and thalamus). Ongoing research is being aggressively pursued to stop this feed-forward cycle in its tracks. Medications that may exacerbate tinnitus (adapted from Bailey's Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 4th ed.) include aspirin and aspirin-containing compounds, aminoglycoside antibiotics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and heterocycline antidepressants.