Workforce Development and Unemployment Insurance Provisions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEA Fact Sheet

WHAT IS THE SEA PROGRAM? The Self-Employment Assistance (SEA) program offers qualifying dislocated workers the opportunity for early re-employment through self-employment. The program is designed to encourage and enable unemployed workers to create their own jobs by starting their own small businesses. States operating an SEA program can pay an SEA allowance, instead of regular unemployment insurance benefits, to help unemployed workers while they are establishing businesses and becoming self-employed. Participants receive weekly allowances while they are getting their businesses off the ground. ELIGIBILTY REQUIREMENTS To receive these benefits, an individual must first be eligible to receive regular unemployment insurance under State law. Indiviuals who have been permanently separated from their previous employment and are identified as likely to exhaust regular unemployment benefits are eligible to apply for the program along with other program requirements as designated by the state. Individuals who are found eligible for SEA must engage in full-time self-employment activities in accordance with the state’s SEA program - including entrepreneurial training, business counseling, business plan development, etc. APPLICATION PROCESS SEA is a voluntary state program. To date, there are five SEA states. For more information on each state’s SEA program and requirements, visit the state’s UI agency’s website. } Delaware (Note: See agency “Contact” instructions to obtain SEA program information) } Mississippi } New Hampshire } New York } Oregon ADDITIONAL SEA INFORMATION You can obtain additional SEA information through the Self-Employment Assistance Center. The U.S. Department of Labor, in partnership with the Small Business Administration, created the Self-Employment Assistance Center to provide information, resources, and tools to help build state entrepreneurial programs for individuals eligible for Unemployment Insurance compensation. -

Marx, the Present Crisis and the Future of Labour*

MARX, THE PRESENT CRISIS AND THE FUTURE OF LABOUR* Ernest Mandel For several years, the political thesis that human emancipation can no longer rely on the 'proletariat', the class of wage labour, has been increasingly buttressed by economic arguments. Some posit that wage labour is receding rapidly from its position as the main sector of the active population, as the result of automation, robotisation, mass unemployment, growth of small independent business firms, etc. (Gorz, Dahrendorf, Daniel Bell, Hobsbawm).' Others state that there is no future for mankind (and therefore for human emancipation) as long as 'classical' industrial techno- logy and thence 'classical' wage labour are maintained at their present level because such a situation would lead to a complete destruction of the ecological balance (Ilitch, Bahro, G~rz).~The present crisis is therefore seen not as a typical crisis of overproduction and overaccumulation. It is seen as a fundamental change of structure of the international capitalist economy, with a long-term fundamental shift in the weight, cohesion and dynamic of wage labour, at the expense of that class, as a 'crisis of the industrial system'. Can this hypothesis be verified empirically? If not, what is the meaning and what are the long-term potential consequences of growing structural unemployment, which, in and by itself, is an undeniable phenomenon? If yes, what is the explanation of the phenomenon of the supposed 'decline of the working class' as an objective phenomenon? What are its potential economic consequences? Empirically, the basic trend which is statistically verifiable is that of the growth of wage labour on a world scale, and on all continents, and not that of its absolute or relative decline. -

Non State Employer Group Employee Guidebooks

STATE EMPLOYEE HEALTH PLAN NON-STATE GROUP EMPLOYEES BENEFIT GUIDEBOOK PLAN YEAR 2020 - 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS VENDOR CONTACT INFORMATION .............................................................................................................. 2 MEMBERSHIP ADMINISTRATION PORTAL .................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 4 GENERAL DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................ 5 EMPLOYEE ELIGIBILITY ................................................................................................................................ 7 OTHER ELIGIBLE INDIVIDUALS UNDER THE SEHP .................................................................................... 9 ANNUAL OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD ...................................................................................................... 16 MID-YEAR ENROLLMENT CHANGES .......................................................................................................... 17 LEAVE WITHOUT PAY AND RETURN FROM LEAVE WITHOUT PAY …………………………………………22 FAMILY MEDICAL LEAVE ACT(FMLA), FURLOUGHS AND LAYOFFS ……………………………………….23 HEALTH INSURANCE PORTABILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY ACT (HIPAA) ............................................ 24 FLEXIBLE SPENDING ACCOUNT PROGRAM - 2021 .................................................................................. -

The Budgetary Effects of the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 February 2021

The Budgetary Effects of the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 FEBRUARY 2021 If enacted at the end of March 2021, the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 (S. 53, as introduced on January 26, 2021) would raise the federal minimum wage, in annual increments, to $15 per hour by June 2025 and then adjust it to increase at the same rate as median hourly wages. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office estimates the bill’s effects on the federal budget. The cumulative budget deficit over the 2021–2031 period would increase by $54 billion. Increases in annual deficits would be smaller before 2025, as the minimum-wage increases were being phased in, than in later years. Higher prices for goods and services—stemming from the higher wages of workers paid at or near the minimum wage, such as those providing long-term health care—would contribute to increases in federal spending. Changes in employment and in the distribution of income would increase spending for some programs (such as unemployment compensation), reduce spending for others (such as nutrition programs), and boost federal revenues (on net). Those estimates are consistent with CBO’s conventional approach to estimating the costs of legislation. In particular, they incorporate the assumption that nominal gross domestic product (GDP) would be unchanged. As a result, total income is roughly unchanged. Also, the deficit estimate presented above does not include increases in net outlays for interest on federal debt (as projected under current law) that would stem from the estimated effects of higher interest rates and changes in inflation under the bill. -

Workers and Labour in a Globalised Capitalism

Workers and Labour in a Globalised Capitalism MANAGEMENT, WORK & ORGANISATIONS SERIES Series editors: Gibson Burrell, School of Management, University of Leicester, UK Mick Marchington, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester and Strathclyde Business School, University of Strathclyde, UK Paul Thompson, Strathclyde Business School, University of Strathclyde, UK This series of textbooks covers the areas of human resource management, employee relations, organisational behaviour and related business and management fields. Each text has been specially commissioned to be written by leading experts in a clear and accessible way. The books contain serious and challenging material, take an analytical rather than prescriptive approach and are particularly suitable for use by students with no prior specialist knowledge. The series is relevant for many business and management courses, including MBA and post-experience courses, specialist masters and postgraduate diplomas, professional courses and final-year undergraduate courses. These texts have become essential reading at business and management schools worldwide. Published titles include: Maurizio Atzeni WORKERS AND LABOUR IN A GLOBALISED CAPITALISM Stephen Bach and Ian Kessler THE MODERNISATION OF THE PUBLIC SERVICES AND EMPLOYEE RELATIONS Emma Bell READING MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATION IN FILM Paul Blyton and Peter Turnbull THE DYNAMICS OF EMPLOYEE RELATIONS (3RD EDN) Paul Blyton, Edmund Heery and Peter Turnbull (eds) REASSESSING THE EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIP Sharon C. Bolton EMOTION -

Gender Pay Gaps

Equality and Human Rights Commission Briefing paper 2 Gender pay gaps David Perfect Gender pay gaps David Perfect, Equality and Human Rights Commission © Equality and Human Rights Commission 2011 First published Spring 2011 ISBN 978 1 84206 351 4 Equality and Human Rights Commission Research The Equality and Human Rights Commission publishes research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers and by the Research Team. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate. Please contact the Research Team for further information about other Commission research reports, or visit our website: Research Team Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House The Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0161 829 8500 Website: www.equalityhumanrights.com You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website: http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/ If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Communications Team to discuss your needs at: [email protected] Key findings Men working full-time continue to have higher average (mean) hourly, weekly and annual earnings than women. Across the United Kingdom, the mean full-time gender pay gap (the difference in percentage terms between the average earnings of women and men working full-time) in 2010 was 15.5 per cent for hourly earnings excluding overtime and 21.5 per cent for gross weekly earnings. The gap was wider in weekly than hourly earnings, since men tend to work longer weekly hours than women and are also more likely to receive additional payments, such as overtime. -

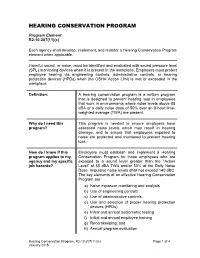

Hearing Conservation Program

HEARING CONSERVATION PROGRAM Program Element R2-10-207(11)(c) Each agency shall develop, implement, and monitor a Hearing Conservation Program element when applicable. Harmful sound, or noise, must be identified and evaluated with sound pressure level (SPL) monitoring devices when it is present in the workplace. Employers must protect employee hearing via engineering controls, administrative controls, or hearing protection devices (HPDs) when the OSHA Action Limit is met or exceeded in the workplace. Definition: A hearing conservation program is a written program that is designed to prevent hearing loss in employees that work in environments where noise levels above 85 dBA or a daily noise dose of 50% over an 8-hour time- weighted average (TWA) are present. Why do I need this This program is needed to ensure employers have program? assessed noise levels which may result in hearing damage, and to ensure that employees exposed to noise are protected and monitored to prevent hearing loss. How do I know if this Employers must establish and implement a Hearing program applies to my Conservation Program for those employees who are agency and my specific exposed to a sound level greater than the “Action job hazards? Level” of 85 dBA TWA and/or 50% of the Daily Noise Dose. Impulsive noise levels shall not exceed 140 dBC. The key elements of an effective Hearing Conservation Program are: a) Noise exposure monitoring and analysis b) Use of engineering controls c) Use of administrative controls d) Use and selection of proper hearing protection devices (HPDs) e) Initial and annual audiometric testing f) Initial and annual employee training g) Recordkeeping; and h) Annual program evaluation Hearing Conservation Program, R2-10-207(11)(c) Page 1 of 4 January 2015 What are the minimum There are five OSHA required Hearing Conservation required elements and/ Program elements: or best practices for a Hearing Conservation 1. -

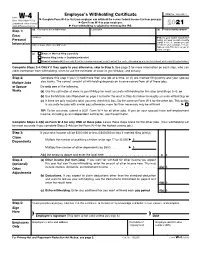

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

MINIMUM WAGE Sheryl Maxfield Director

Mike DeWine Governor STATE OF OHIO Jon Husted Lt. Governor 2021 MINIMUM WAGE Sheryl Maxfield www.com.ohio.gov Director NON-TIPPED EMPLOYEES A Minimum Wage of $8.80 per hour “Non-Tipped Employees” includes any employee who does not engage in an occupation in which he/she customarily and regularly receives more than thirty dollars ($30.00) per month in tips. “Employers” who gross less than $323,000 shall pay their employees no less than the current federal minimum wage rate. “Employees” under the age of 16 shall be paid no less than the current federal minimum wage rate. “Current Federal Minimum Wage” is $7.25 per hour. TIPPED EMPLOYEES A Minimum Wage of $4.40 per hour PLUS TIPS “Tipped Employees” includes any employee who engages in an occupation in which he/she customarily and regularly receives more than thirty dollars ($30.00) per month in tips. Employers electing to use the tip credit provision must be able to show that tipped employees receive at least the minimum wage when direct or cash wages and the tip credit amount are combined. OVERTIME INDIVIDUALS EXEMPT FROM MINIMUM WAGE 1. An employer shall pay an employee for overtime at a wage rate of one and one-half times the employee’s wage rate for hours in 1. Any individual employed by the United States; excess of 40 hours in one work week, except for employers grossing less than $150,000 per year. 2. Any individual employed as a baby-sitter in the employer’s home, RECORDS TO BE KEPT BY THE EMPLOYER or a live-in companion to a sick, convalescing, or elderly person whose principal duties do not include housekeeping; 1. -

Unemployment Benefits and Unemployment in the Great Recession: the Role of Macro Effects

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS AND UNEMPLOYMENT IN THE GREAT RECESSION: THE ROLE OF MACRO EFFECTS Marcus Hagedorn Fatih Karahan Iourii Manovskii Kurt Mitman Working Paper 19499 http://www.nber.org/papers/w19499 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2013 We would like to thank Bob Hall, Sam Schulhofer-Wohl and seminar participants at Census Bureau, Edinburgh, EIEF, USC, Maryland, Penn State, UPenn, Princeton, Pompeu Fabra, Toulouse, UCL, UConn, Wisconsin, CUNY Graduate Center, Greater Stockholm Macro Group, Federal Reserve Banks of Cleveland, New York, and Philadelphia, 2013 conference on Macroeconomics Across Time and Space, 2013 SED, 2013 NBER Summer Institute (EFCE, EFMB, EFRSW groups), 2013 North American Summer Meeting of Econometric Society, 2013 Minnesota Workshop in Macroeconomic Theory, 15th IZA/CEPR European Summer Symposium on Labor Economics, Mannheim conference on \Financial Frictions and Real Economy," 4th Ifo Conference on "Macroeconomics and Survey Data", 2014 ASSA Meetings, 2014 NBER Public Economics Program Meeting and 2014 Cowles Foundation Summer Conference on \Structural Empirical Microeconomic Models" for their comments. We are especially grateful to June Shelp, at The Conference Board, for her help with the HWOL data. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Support from the National Science Foundation Grants No. SES-0922406 and SES-1357903 is gratefully acknowledged. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve System, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

Neoliberal Austerity and Unemployment

E L C I ‘…following Stuckler and Basu (2013) T it is not economic downturns per se that R matter but the austerity and welfare A “reform” that may follow: that “austerity Neoliberal austerity kills” and – as I argue here – that it particularly “kills” those in lower socio- economic positions.’ and unemployment The scale of contemporary unemployment consequent upon David Fryer and Rose Stambe examine critical psychological issues neoliberal austerity programmes is colossal. According to labour market statistics released in June 2013 by the UK Neoliberal fiscal austerity policies I am really sorry to bother you again. Office for National Statistics, 2.51 million decrease public expenditure God. But I am bursting to tell you all people were unemployed in the UK through cuts to central and local the stuff that has been going on (tinyurl.com/neu9l47). This represents five government budgets, welfare behind your back since I first wrote to unemployed people competing for every services and benefits and you back in 1988. Oh God do you still vacancy. privatisation of public resources remember? Remember me telling Official statistics like these, which have resulting in job losses. This article you of the war that was going on persisted now for years, do not, of course, interrogates the empirical, against the poor and unemployed in prevent the British Prime Minister – theoretical, methodological and our working class communities? Do evangelist of neoliberal government - ideological relationships between you remember me telling you, God, asking in a speech delivered in June 2012 neoliberalism, unemployment and how the people in my community ‘Why has it become acceptable for many the discipline of psychology, were being killed and terrorised but people to choose a life on benefits?’ arguing that neoliberalism that there were no soldiers to be Talking of what he termed ‘Working Age constitutes rather than causes seen, no tanks, no bombs being Welfare’, Mr Cameron opined: ‘we have unemployment. -

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗

Unemployment in an Extended Cournot Oligopoly Model∗ Claude d'Aspremont,y Rodolphe Dos Santos Ferreiraz and Louis-Andr´eG´erard-Varetx 1 Introduction Attempts to explain unemployment1 begin with the labour market. Yet, by attributing it to deficient demand for goods, Keynes questioned the use of partial analysis, and stressed the need to consider interactions between the labour and product markets. Imperfect competition in the labour market, reflecting union power, has been a favoured explanation; but imperfect competition may also affect employment through producers' oligopolistic behaviour. This again points to a general equilibrium approach such as that by Negishi (1961, 1979). Here we propose an extension of the Cournot oligopoly model (unlike that of Gabszewicz and Vial (1972), where labour does not appear), which takes full account of the interdependence between the labour market and any product market. Our extension shares some features with both Negishi's conjectural approach to demand curves, and macroeconomic non-Walrasian equi- ∗Reprinted from Oxford Economic Papers, 41, 490-505, 1989. We thank P. Champsaur, P. Dehez, J.H. Dr`ezeand J.-J. Laffont for helpful comments. We owe P. Dehez the idea of a light strengthening of the results on involuntary unemployment given in a related paper (CORE D.P. 8408): see Dehez (1985), where the case of monopoly is studied. Acknowledgements are also due to Peter Sinclair and the Referees for valuable suggestions. This work is part of the program \Micro-d´ecisionset politique ´economique"of Commissariat G´en´eral au Plan. Financial support of Commissariat G´en´eralau Plan is gratefully acknowledged.