Saint Laurent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cutting Edge of French Cinema

BACKWASH: THE CUTTING EDGE OF FRENCH CINEMA J’IRAI AU PARADIS CAR L’ENFER EST ICI , Xavier Durringer ( France, 1997 ) MA 6T VA CRACK-ER , Jean-Francois Richet ( France, 1997 ) LE PETIT VOLEUR , Érick Zonca ( France, 1998 ) L’HUMANITÉ , Bruno Dumont ( France, 1999 ) POLA X , Leos Carax ( France, 1999 ) RESSOURCES HUMAINES (Human Resources), Laurent Cantet ( France, 1999 ) À MA SOEUR! , Catherine Breillat ( France-Italy, 2000 ) PARIA , Nicolas Klotz ( France, 2000 ) SAINT-CYR , Patricia Mazuy ( France-Belgium, 2000 ) SELON MATTHIEU , Xavier Beauvois ( France, 2000 ) SOUS LE SABLE , François Ozon ( France-Belgium-Italy-Japan, 2000 ) ÊTRE ET AVOIR , Nicolas Philibert ( France, 2001 ) IRRÉVERSIBLE (Irreversible), Gaspar Noé ( France, 2001 ) LA CHATTE À DEUX TÊTES , Jacques Nolot ( France, 2001 ) LA VIE NOUVELLE , Philippe Grandrieux ( France, 2001 ) LE PACTE DES LOUPS , Christophe Gans ( France, 2001 ) LE STADE DE WIMBLEDON , Mathieu Amalric ( France, 2001 ) ROBERTO SUCCO , Cédric Kahn ( France-Switzerland, 2001 ) TROUBLE EVERY DAY , Claire Denis ( France-Japan, 2001 ) DANS MA PEAU , Marina De Van ( France, 2002 ) UN HOMME, UN VRAI , Jean-Marie Larrieu, Arnaud Larrieu ( France, 2002 ) CLEAN , Olivier Assayas ( France-UK-Canada, 2003 ) INNOCENCE , Lucile Hadzihalilovic ( France-UK-Belgium, 2003 ) L’ESQUIVE , Abdellatif Kechiche ( France, 2003 ) LE CONVOYEUR , Nicolas Boukhrief ( France, 2003 ) LES CORPS IMPATIENTS , Xavier Giannoli ( France, 2003 ) ROIS ET REINE , Arnaud Desplechin ( France-Belgium, 2003 ) TIRESIA , Bertrand Bonello ( France, 2003 ) DE BATTRE MON COEUR S’EST ARRÊTÉ (The Beat That My Heart Skipped), Jacques Audiard ( France, 2004 ) LES REVENANTS , Robin Campillo ( France, 2004 ) LES ANGES EXTERMINATEURS , Jean-Claude Brisseau ( France, 2005 ) VOICI VENU LE TEMPS , Alain Guiraudie ( France, 2005 ) À L’INTERIEUR , Alexandre Bustillo, Julien Maury ( France, 2006 ) AVIDA , Benoît Delépine, Gustave Kervern ( France, 2006 ) LES CHANSONS D’AMOUR , Christophe Honoré ( France, 2006 ) 24 MESURES , Jalil Lespert ( France-Canada, 2007 ) L’HISTOIRE DE RICHARD O. -

QUEER FILM Anniversary FESTIVAL #BQFF2019

THE BANGALORE 10th QUEER FILM Anniversary FESTIVAL #BQFF2019 I'm crying cuz I love you We’ve turned ten! And we didn’t make it so far on our own. One of the several perks of being a volunteer-run, community- funded event has been that friends from the community and of the community have come in, rolled up their sleeves, hitched up their hemlines and taken charge over the many years. From the first public film festival called ‘Bangalored’, held with our signature spread of mattresses at the Attakkalari Studios and helmed by the good folks of Pedestrian Pictures, Swabhava’s Vinay Chandran (who remains the longest- running festival director), Sangama, and the funding prowess of Bangalore’s former party starter Abhishek Agarwal, to the smaller festivals organised at a screening room in the Sona Towers, to its present avatar as the Bangalore Queer Film Festival – this festival has become its own beauty, its own beast. Over this decade-long journey, we’ve been held and nurtured by support groups like Good As You, We’re Here And Queer and All Sorts of Queers; individuals like Karthik Vaidyanathan, Nanju Reddy and Siddharth Narrain (who were part of the organising team in the early editions) and organisations like the Alliance Française de Bangalore and Goethe Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan. A question that everyone involved with the festival asks at its end: How did we make this happen again? And while we’ve come up with lots of lies to drive out these doubts, in truth: we have no real idea. -

Film Lives Heresm

TITANUS Two Women BERTRAND BONELLO NEW YORK AFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL MARTÍN REJTMAN TITANUS OPEN ROADS: NEW ITALIAN CINEMA HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH FILM FESTIVAL NEW YORK ASIAN FILM FESTIVAL SPECIAL PROGRAMS NEW RELEASES EMBASSY / THE KOBAL COLLECTION / THE KOBAL EMBASSY MAY/JUN 2015SM FILM LIVES HERE Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center 144 W 65th St | Walter Reade Theater 165 W 65th St | filmlinc.com | @filmlinc HERE STARTS PROGRAMMING SPOTLIGHT TABLE OF CONTENTS I PUT A SPELL ON YOU: THE FILMS OF BERTRAND BONELLO Festivals & Series 2 I Put a Spell on You: The Films of Bertrand Bonello (Through May 4) 2 PROVOKES PROVOKES Each new Bertrand Bonello film is an event in and of itself.Part of what makes Bonello’s work so thrilling is that, with some exceptions, world cinema has yet to catch up with his New York African Film Festival (May 6 – 12) 4 unique combination of artistic rigor and ability to distill emotion from the often extravagantly Sounds Like Music: The Films of Martín Rejtman (May 13 – 19) 7 stylish, almost baroque figures, places, and events that he portrays. He already occupies Titanus (May 22 – 31) 8 HERE FILM a singular place in French cinema, and we’re excited that our audiences now have the Open Roads: New Italian Cinema (June 4 – 11) 12 opportunity to discover a body of work that is unlike any other. –Dennis Lim, Director of Programming Human Rights Watch Film Festval (June 12 – 20) 16 New York Asian Film Festival (June 26 – July 8) 17 HERE FILM Special Programs 18 INSPIRES TITANUS Sound + Vision Live (May 28, June 25) 18 We have selected 23 cinematic gems from the Locarno Film Festival’s tribute to Titanus. -

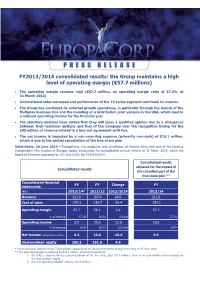

FY2013/2014 Consolidated Results: the Group Maintains a High Level of Operating Margin (€57.7 Millions)

FY2013/2014 consolidated results: the Group maintains a high level of operating margin (€57.7 millions) The operating margin remains high (€57.7 million, an operating margin ratio of 27.3% at 31 March 2014) International sales increased and performance of the TV series segment continued to improve The Group has continued its external growth operations, in particular through the launch of the Multiplex business line and the founding of a distribution joint venture in the USA, which lead to a reduced operating income for the financial year The statutory auditors have stated that they will issue a qualified opinion due to a divergence between their technical analysis and that of the Company over the recognition timing for the $45 million of revenue related to a buy-out agreement with Fox. The net income is impacted by a non-recurring expense (primarily non-cash) of €10.1 million, which is due to the partial cancellation of the free share plan Saint-Denis, 26 June 2014 – EuropaCorp, the producer and distributor of feature films and one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, today announces its consolidated annual results at 31 March 2014, which the Board of Directors approved on 25 June 2014, for FY2013/2014. Consolidated results adjusted for the impact of Consolidated results the cancelled part of the free share plan ** Consolidated financial FY FY Change FY statements (€m) 2013/14* 2012/13 2013/2014 2013/14 Revenue 211.8 185.8 26.0 211,8 Cost of sales -154.1 -129.7 -24.4 -154.1 Operating margin 57.7 56.1 1.6 57.7 % of revenue -

Bertrand Bonello « Il a Fallu Que Je Trouve Mon Chemin De Manière Relativement Solitaire » Sami Gnaba

Document generated on 09/26/2021 12:12 p.m. Séquences : la revue de cinéma Bertrand Bonello « Il a fallu que je trouve mon chemin de manière relativement solitaire » Sami Gnaba On the beach At night Alone Number 308, June 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/86039ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gnaba, S. (2017). Bertrand Bonello : « Il a fallu que je trouve mon chemin de manière relativement solitaire ». Séquences : la revue de cinéma, (308), 38–43. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 38 | ARRÊT SUR IMAGE | ENTREVUE Bertrand Bonello « Il a fallu que je trouve mon chemin de manière relativement solitaire » Dans ce long entretien, Bertrand Bonello revient sur l'origine, la fabrication et la réception de Nocturama, son plus récent film. Mais aussi, plus largement, sur sa filmographie, que nous avons revisitée avec lui au cours de notre échange, l'interrogeant notamment sur sa méthode de travail, l’importance de la musique dans ses films, son attachement au court métrage ou encore son rapport au cinéma français. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Finite Rants” from 25 June 2020

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE ONLINE PROJECT “FINITE RANTS” FROM 25 JUNE 2020 Milan, 17 July 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the online project “Finite Rants”, curated by Luigi Alberto Cippini and Niccolò Gravina, on its website and social platforms from 25 June 2020. Commissioned by Fondazione Prada to filmmakers, artists, intellectuals and scholars, the 8 visual essays comprised in “Finite Rants” will be published on a monthly basis. The first authors include German director and writer Alexander Kluge, Japanese photographer Satoshi Fujiwara, French director Bertrand Bonello, and Swiss economist Christian Marazzi. As stated by avant-garde director Hans Richter in 1940, the film or video essay is a form of expression capable of creating “images for mental notions” and of portraying concepts. Starting from Richter's ideas, some later theorists identify specific traits in the video essay, such as creative freedom, complexity, reflexivity, the crossing of film genres and the transgression of linguistic conventions. “Finite Rants” aims to test the versatility of the visual essay in expressing thought images and demonstrate its relevance in contemporary visual production. According to the two curators, “this project further develops Richter's intuitions starting from the assumption that, due to the natural evolutionary condition of the cinematographic fact and its contamination with forms of information, visual material and capillary distribution of Image Capture supports, today more than ever it is necessary to search for what can be defined as ‘Formatless Dogma’, in support of a visual production without restrictions". The aesthetic and theoretical roots of “Finite Rants” can be traced back to the experimental work La Jetée (1962) by French author Chris Marker. -

Alexander Wang

Fashion. Beauty. Business. APRIL 2015 No.1 Alexander Wang The Six Who will build the powerhouse brands US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1500 of tomorrow? CANADA $13 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG HK100 A look at six of the EUROPE € 11 INDIA 800 industry’s best bets. Fashion. Beauty. Business. APRIL 2015 No.1 The Row The Six Who will build the powerhouse brands US $9.99 JAPAN ¥1500 of tomorrow? CANADA $13 CHINA ¥80 UK £ 8 HONG KONG HK100 A look at six of the EUROPE € 11 INDIA 800 industry’s best bets. Christopher Kane J.W. Anderson Introducing the ricky drawstring 888.475.7674 ralphlauren.com The Ricky Sunglass ARMANI.COM/ATRIBUTE 800.929.Dior (3467) Dior.com © 2015 Estée Lauder Inc. © 2015 DRIVEN BY DESIRE esteelauder.com NEW. PURE COLOR ENVY SHINE On Carolyn: Empowered Sculpt. Hydrate. Illuminate. NEW ORIGINAL HIGH-IMPACT CREME AND NEW SHINE FINISH Contents Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Alexander J.W. Wang The Row Anderson Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Fashion. Beauty. Business. Chitose Christopher Proenza Abe Kane Schouler Six Covers Photographer Nigel Parry shot the designers for the cover story during a whirlwind global tour. “To be asked to photograph the covers for the launch of the new WWD weekly is a gift to any photographer,” he said. “I’m not saying it was easy — eight designers, six days, three continents — but the jet-lag was kept at bay by meeting such great talents. Thank you WWD!” Cover Story The 168 Fashion has long been obsessed with the new, the fresh, the unexpected, never more so than now. -

Myfrenchfilmfestival-2017.Pdf

PRESENTS MY FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL .COM JAN 13 - FEB 13, 2017 7 TH EDITION ONLINE FESTIVAL WORLDWIDE 10 FEATURE FILMS 10 SHORT FILMS 10 LANGUAGES MY FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL + RDV CINEMA FRANCAIS • 170 x 220 mm • PPR • Q • VISUEL : MAN • Remise le 05/12 OM • BAT La vie est un sport magnifique LACO_1610270_Man_170x220.indd 1 05/12/2016 10:32 É DITORIAUX / E DITORIALS P.4 P LATEFORMES PARTENAIRES / P ARTN E R P L AT F O R M S P.6 M Y F RENCH F ILM F E ST I VA L P.9 N OUVEAUT É S / W H AT ’ S N ew P.10 P RIX & TARIFS / A WARDS & R AT E S P.11 J URY DES C IN É ASTES / D IR E CTORS ’ J URY P.12 J URY DE LA P RESSE I NTERNATIONALE / I NT E R N AT I O N A L P R E SS J URY P.14 P RO J ECTIONS P UBLIQUES / P UBLIC SCR ee NINGS P.17 C ONCOURS / C ONT E STS P.19 I LS AIMENT LE F E ST I VA L / T H E Y LIK E TH E F E ST I VA L P.20 I NDEX DES FILMS / M OVI E IND E X P.21 L A S É LECTION / T H E S E L E CTION C OMING OF A G E P.22 W E A R E F A M I LY P.32 L OV E & F RI E NDSHI P P.40 P SYCHO P.46 A W OMAN ’ S L IF E P.54 M IDNIGHT S CR ee NINGS P.62 J URYS P R É C É DENTS / P R E VIOUS J URI E S P.69 P ALMARÈS DES É DITIONS P R É C É DENTES / P R E VIOUS AWARDS P.71 U NI F RANCE P.73 P ARTENAIRES / P ARTN E RS P.74 MA RELATION AVEC LE CINÉMA FRANÇAIS a commencé bien avant que je devienne réalisateur. -

SOPHIA LATJUBA Her Passion of Life

MAGAZINE OF SENAYAN CITY winter 2017 Beautiful Young Mothers SABAI DIETER MORSCHEK MIKAILA PATRITZ YASMINE WILDBLOOD Winter Travel To Reykjavik SOPHIA LATJUBA HER PASSION OF LIFE A Celebration of Festive season in-Chief ED ITOR EKSEKUTIF Halina E-MAIL PROMOSI DAN IklaN E-mail: [email protected] Call Center: 021-7278 1000 DIterbItkaN OLEH Senayan City BEKERJA SAMA DENGAN MRA Media Special Project Division Wisma MRA Jl. TB. Simatupang HNALI A No.19 Cilandak Barat mark ETING dirECTOR SENAYAN citY Jakarta Selatan 12430 Tel: (021) 2765-1717/18 A Celebration Of Festive Seasons. Menjelang akhir tahun, sejumlah persiapan menyambut. Natal, Tahun Baru, dan Imlek TIM EDItorIAL adalah rangkaian perayaan yang ditunggu-tunggu hingga tahun Miranti M. Lemy Eddy Sofyan depan. Oleh sebab itu, kami menyajikan sejumlah artikel yang Agung C. Widi Insan Obi mengangkat berbagai event istimewa tersebut sebagai topik Firisa Ardianti Saffie Adjie Badas dalam edisi winter 2017 ini. Anda akan menemukan the latest Kiky Septika Anjani Iqbal trend untuk Cruise Collection dan rekomendasi kami tentang Aristya Rizky Badzlina Veby Citra gaya earthy tone untuk tahun 2018. Gusti Aditya Abiprasiasti Dalam edisi ini, sebagai cover, kami menampilkan iconic Bungbung Mangaraja Riza Adam Buchori telented figures yang juga merupakan ibu dan anak yang Hadi Cahyono berprestasi yang kisahnya juga dapat Anda simak dalam cover story. Simak juga laporan kami mengenai sejumlah new spots di Senayan City yang wajib Anda kunjungi, serta liputan mendalam dari perhelatan JFW 2018 yang diikuti oleh kisah sukses sejumlah Jakarta Fashion Week 2017. Ikuti kisah sukses COVER sejumlah profil tokoh desainer fashion yang kini tengah menjadi Model: Sophia Latjuba the talk of the town untuk referensi Anda. -

Agathe Bonitzer

AIRF_1905302 • MRS 13 - Presse Mag.FID MARSEILLE • SP + 5 mm de débord • 150 x 200 mm • Visuel : Divertissement • Parution 01/juin/2019 • Remise le 31/mai/2019 ILG• BAT SPECTACULAIRE!! Nouvel écran tactile!: découvrez un écran HD plus grand pour profiter des dernières sorties cinéma, des dessins animés, de la musique et des jeux vidéo, depuis le décollage jusqu’à l’atterrissage. AIRFRANCE.FR France is in the air : La France est dans l’air. Mise en place progressive sur une partie de la flotte long-courrier Boeing 777 et Boeing 787. AIRF_1905302_MRS13_DIVERTISSEMENT_FID_MARSEILLE_150x200_PM.indd 1 29/05/2019 12:36 LE SITE. L'APPLI. LA CHAÎNE. REGARDEZ À TRAVERS LA LUCARNE Dédiée au documentaire de création, La Lucarne est une fenêtre ouverte sur la diversité des réels, des vécus et des imaginaires. Le lundi aux alentours de minuit sur ARTE. En replay sur arte.tv et YouTube. © Elliott Erwitt VOUS AIMEZ DÉJÀ Elliott Erwitt - Silence Sounds GoodSounds Silence - Erwitt Elliott 30e Festival International de Cinéma Marseille 9 — 15 juillet 2019 Sommaire / Contents 4 Partenaires / Partners & sponsors 146 Écrans parallèles / Parallel screenings 148 Hommage à Sharon Lockhart 6 Éditoriaux / Editorials 158 Hommage à Bertrand Bonello 166 Histoire(s) de Portrait 15 Prix / Awards 182 Des marches, démarches 20 Jurys / Juries 204 Cinéma sans recettes 22 Jury de la Compétition Internationale / International Competition jury 208 Les Années Scopitones 28 Jury de la Compétition Française / French Competition jury 214 Les Sentiers – Les Sentiers Expanded 34 -

House of Tolerance English Subtitles

House of tolerance english subtitles click here to download English www.doorway.ru, 1, amam. not perfect but tried to bring it close enough!!! English www.doorway.runceDVDRip, 1. English subtitle for House of Tolerance (House of Pleasures / L'Apollonide / Souvenirs de la maison close). Download House of Tolerance English YIFY YTS Subtitles. 0, English, Subtitle House of Tolerance AKA House of Pleasures dvdrip lpd, YTS. Download the popular multi language subtitles for House Of Tolerance Dvdrip. www.doorway.ru English. English subtitle (English subtitles). · www.doorway.ru English subtitle (English subtitles). L'Apollonide (Souvenirs. House Of Tolerance: {3} english (en) subtitles. Download and convert House of Tolerance movie subtitle in one of the following formats SRT. Download L'Apollonide (Souvenirs de la maison close) {(House of Tolerance AKA House of Pleasures)} subtitles. english subtitles. Watch online House of Tolerance full with English subtitle. Watch online free House of Tolerance, Hafsia Herzi, Jasmine Trinca, Noémie Lvovsky, Adèle. Download HOUSE OF TOLERANCE English Download subtitles. House of Pleasures - L'Apollonide: Souvenirs de la maison close Bertrand Bonello; ; France; French with English subtitles; 35mm; Life in an elegant Parisian brothel in the early twentieth century. The madam essentially owns the women: their. Full MOVIE Legit Link:: (www.doorway.ru) ▷▷ House of Tolerance FULL MOVIE House of Tolerance FULL MOVIE | House of. House of Tolerance (Souvenirs de la maison close) Duration: 2h5m; Country: France; Format: Digital; Year: ; Language: French with English subtitles. Find House of Tolerance [Region 2] [UK Import] at www.doorway.ru Movies & TV, Digital Stereo), English (Subtitles), ANAMORPHIC WIDESCREEN (). WITH ENGLISH SUBTITLES.