Bertrand Bonello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cutting Edge of French Cinema

BACKWASH: THE CUTTING EDGE OF FRENCH CINEMA J’IRAI AU PARADIS CAR L’ENFER EST ICI , Xavier Durringer ( France, 1997 ) MA 6T VA CRACK-ER , Jean-Francois Richet ( France, 1997 ) LE PETIT VOLEUR , Érick Zonca ( France, 1998 ) L’HUMANITÉ , Bruno Dumont ( France, 1999 ) POLA X , Leos Carax ( France, 1999 ) RESSOURCES HUMAINES (Human Resources), Laurent Cantet ( France, 1999 ) À MA SOEUR! , Catherine Breillat ( France-Italy, 2000 ) PARIA , Nicolas Klotz ( France, 2000 ) SAINT-CYR , Patricia Mazuy ( France-Belgium, 2000 ) SELON MATTHIEU , Xavier Beauvois ( France, 2000 ) SOUS LE SABLE , François Ozon ( France-Belgium-Italy-Japan, 2000 ) ÊTRE ET AVOIR , Nicolas Philibert ( France, 2001 ) IRRÉVERSIBLE (Irreversible), Gaspar Noé ( France, 2001 ) LA CHATTE À DEUX TÊTES , Jacques Nolot ( France, 2001 ) LA VIE NOUVELLE , Philippe Grandrieux ( France, 2001 ) LE PACTE DES LOUPS , Christophe Gans ( France, 2001 ) LE STADE DE WIMBLEDON , Mathieu Amalric ( France, 2001 ) ROBERTO SUCCO , Cédric Kahn ( France-Switzerland, 2001 ) TROUBLE EVERY DAY , Claire Denis ( France-Japan, 2001 ) DANS MA PEAU , Marina De Van ( France, 2002 ) UN HOMME, UN VRAI , Jean-Marie Larrieu, Arnaud Larrieu ( France, 2002 ) CLEAN , Olivier Assayas ( France-UK-Canada, 2003 ) INNOCENCE , Lucile Hadzihalilovic ( France-UK-Belgium, 2003 ) L’ESQUIVE , Abdellatif Kechiche ( France, 2003 ) LE CONVOYEUR , Nicolas Boukhrief ( France, 2003 ) LES CORPS IMPATIENTS , Xavier Giannoli ( France, 2003 ) ROIS ET REINE , Arnaud Desplechin ( France-Belgium, 2003 ) TIRESIA , Bertrand Bonello ( France, 2003 ) DE BATTRE MON COEUR S’EST ARRÊTÉ (The Beat That My Heart Skipped), Jacques Audiard ( France, 2004 ) LES REVENANTS , Robin Campillo ( France, 2004 ) LES ANGES EXTERMINATEURS , Jean-Claude Brisseau ( France, 2005 ) VOICI VENU LE TEMPS , Alain Guiraudie ( France, 2005 ) À L’INTERIEUR , Alexandre Bustillo, Julien Maury ( France, 2006 ) AVIDA , Benoît Delépine, Gustave Kervern ( France, 2006 ) LES CHANSONS D’AMOUR , Christophe Honoré ( France, 2006 ) 24 MESURES , Jalil Lespert ( France-Canada, 2007 ) L’HISTOIRE DE RICHARD O. -

Film Lives Heresm

TITANUS Two Women BERTRAND BONELLO NEW YORK AFRICAN FILM FESTIVAL MARTÍN REJTMAN TITANUS OPEN ROADS: NEW ITALIAN CINEMA HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH FILM FESTIVAL NEW YORK ASIAN FILM FESTIVAL SPECIAL PROGRAMS NEW RELEASES EMBASSY / THE KOBAL COLLECTION / THE KOBAL EMBASSY MAY/JUN 2015SM FILM LIVES HERE Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center 144 W 65th St | Walter Reade Theater 165 W 65th St | filmlinc.com | @filmlinc HERE STARTS PROGRAMMING SPOTLIGHT TABLE OF CONTENTS I PUT A SPELL ON YOU: THE FILMS OF BERTRAND BONELLO Festivals & Series 2 I Put a Spell on You: The Films of Bertrand Bonello (Through May 4) 2 PROVOKES PROVOKES Each new Bertrand Bonello film is an event in and of itself.Part of what makes Bonello’s work so thrilling is that, with some exceptions, world cinema has yet to catch up with his New York African Film Festival (May 6 – 12) 4 unique combination of artistic rigor and ability to distill emotion from the often extravagantly Sounds Like Music: The Films of Martín Rejtman (May 13 – 19) 7 stylish, almost baroque figures, places, and events that he portrays. He already occupies Titanus (May 22 – 31) 8 HERE FILM a singular place in French cinema, and we’re excited that our audiences now have the Open Roads: New Italian Cinema (June 4 – 11) 12 opportunity to discover a body of work that is unlike any other. –Dennis Lim, Director of Programming Human Rights Watch Film Festval (June 12 – 20) 16 New York Asian Film Festival (June 26 – July 8) 17 HERE FILM Special Programs 18 INSPIRES TITANUS Sound + Vision Live (May 28, June 25) 18 We have selected 23 cinematic gems from the Locarno Film Festival’s tribute to Titanus. -

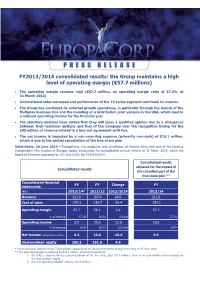

FY2013/2014 Consolidated Results: the Group Maintains a High Level of Operating Margin (€57.7 Millions)

FY2013/2014 consolidated results: the Group maintains a high level of operating margin (€57.7 millions) The operating margin remains high (€57.7 million, an operating margin ratio of 27.3% at 31 March 2014) International sales increased and performance of the TV series segment continued to improve The Group has continued its external growth operations, in particular through the launch of the Multiplex business line and the founding of a distribution joint venture in the USA, which lead to a reduced operating income for the financial year The statutory auditors have stated that they will issue a qualified opinion due to a divergence between their technical analysis and that of the Company over the recognition timing for the $45 million of revenue related to a buy-out agreement with Fox. The net income is impacted by a non-recurring expense (primarily non-cash) of €10.1 million, which is due to the partial cancellation of the free share plan Saint-Denis, 26 June 2014 – EuropaCorp, the producer and distributor of feature films and one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, today announces its consolidated annual results at 31 March 2014, which the Board of Directors approved on 25 June 2014, for FY2013/2014. Consolidated results adjusted for the impact of Consolidated results the cancelled part of the free share plan ** Consolidated financial FY FY Change FY statements (€m) 2013/14* 2012/13 2013/2014 2013/14 Revenue 211.8 185.8 26.0 211,8 Cost of sales -154.1 -129.7 -24.4 -154.1 Operating margin 57.7 56.1 1.6 57.7 % of revenue -

Bertrand Bonello « Il a Fallu Que Je Trouve Mon Chemin De Manière Relativement Solitaire » Sami Gnaba

Document generated on 09/26/2021 12:12 p.m. Séquences : la revue de cinéma Bertrand Bonello « Il a fallu que je trouve mon chemin de manière relativement solitaire » Sami Gnaba On the beach At night Alone Number 308, June 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/86039ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Gnaba, S. (2017). Bertrand Bonello : « Il a fallu que je trouve mon chemin de manière relativement solitaire ». Séquences : la revue de cinéma, (308), 38–43. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 38 | ARRÊT SUR IMAGE | ENTREVUE Bertrand Bonello « Il a fallu que je trouve mon chemin de manière relativement solitaire » Dans ce long entretien, Bertrand Bonello revient sur l'origine, la fabrication et la réception de Nocturama, son plus récent film. Mais aussi, plus largement, sur sa filmographie, que nous avons revisitée avec lui au cours de notre échange, l'interrogeant notamment sur sa méthode de travail, l’importance de la musique dans ses films, son attachement au court métrage ou encore son rapport au cinéma français. -

Finite Rants” from 25 June 2020

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE ONLINE PROJECT “FINITE RANTS” FROM 25 JUNE 2020 Milan, 17 July 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the online project “Finite Rants”, curated by Luigi Alberto Cippini and Niccolò Gravina, on its website and social platforms from 25 June 2020. Commissioned by Fondazione Prada to filmmakers, artists, intellectuals and scholars, the 8 visual essays comprised in “Finite Rants” will be published on a monthly basis. The first authors include German director and writer Alexander Kluge, Japanese photographer Satoshi Fujiwara, French director Bertrand Bonello, and Swiss economist Christian Marazzi. As stated by avant-garde director Hans Richter in 1940, the film or video essay is a form of expression capable of creating “images for mental notions” and of portraying concepts. Starting from Richter's ideas, some later theorists identify specific traits in the video essay, such as creative freedom, complexity, reflexivity, the crossing of film genres and the transgression of linguistic conventions. “Finite Rants” aims to test the versatility of the visual essay in expressing thought images and demonstrate its relevance in contemporary visual production. According to the two curators, “this project further develops Richter's intuitions starting from the assumption that, due to the natural evolutionary condition of the cinematographic fact and its contamination with forms of information, visual material and capillary distribution of Image Capture supports, today more than ever it is necessary to search for what can be defined as ‘Formatless Dogma’, in support of a visual production without restrictions". The aesthetic and theoretical roots of “Finite Rants” can be traced back to the experimental work La Jetée (1962) by French author Chris Marker. -

Saint Laurent

presents SAINT LAURENT A Film by Bertrand Bonello Official Selection Cannes Film Festival 2014 New York Film Festival 2014 (150 min., France, Belgium, 2014) Language: English, Franch Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1028 Queen Street West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com SYNOPSIS 1967-1976 As one of history’s greatest fashion designers entered a decade of freedom, neither came out of it in one piece. 2 CREDITS CAST Yves Saint Laurent GASPARD ULLIEL Pierre Berge JEREMIE RENIER Jacques De Bascher LOUIS GARREL Loulou De Falaise LEA SEYDOUX Anne Marie Munoz AMIRA CASAR Betty Catroux AYMELINE VALADE Monsieur Jean-Pierre MICHA LESCOT Yves Saint Laurent 1989 HELMUT BERGER Mme Duzer VALERIA BRUNI-TEDESCHI Renee VALERIE DONZELLI Talitha ASMINE TRINCA Lucienne DOMINIQUE SANDA FILMMAKERS Director Bertrand Bonello Screenplay Thomas Bidegain and Bertrand Bonello Director of Photography Josee Deshaies Production Designer Katia Wyszkop Costume Designer Anais Romand Casting Richard Rousseau First Assistant Director Elsa Amiel Script Supervisor Elodie Van Beuren Original Score Bertrand Bonello Sound Nicolas Cantin, Nicolas Moreau, Jean-Pierre Laforce Editing Fabrice Rouaud Production Manager Pascal Roussel Post-Production Supervisor Patricia Colombat Produced by Eric Altmayer, Nicolas Altmayer 3 An Interview with Bertrand Bonello How did this project begin? In November 2011, shortly after the release of L’Apollonide, Eric and Nicolas Altmayer asked me if I’d be interested in making a film about Saint Laurent. -

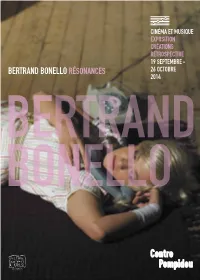

BERTRAND BONELLO RÉSONANCES 26 OCTOBRE 2014 BERTRANDBE BONELLOBON Bertrand Bonello 1

CINÉMA ET MUSIQUE EXPOSITION CRÉATIONS RÉTROSPECTIVE 19 SEPTEMBRE - BERTRAND BONELLO RÉSONANCES 26 OCTOBRE 2014 BERTRANDBE BONELLOBON Bertrand BONELLO 1 SOMMAIRE Musicien de formation, Bertrand Bonello a réalisé depuis le milieu des années 1990 douze films très différents, qui sont autant de prototypes. Son cinéma ne cesse de rechercher et d’expérimenter • Avant-propos, par Alain Seban, p. 1 de nouvelles formes tout en restant délibérément fidèle à un certain classicisme. Ainsi s’adresse-t-il au plus grand nombre tout en l’amenant ailleurs, et autrement. Cet équilibre rare répond • Présentation, par Bertrand Bonello, p. 3 à des questions qui sont au cœur de la création contemporaine et qui s’inscrivent en même temps • Ouverture, par Bertrand Bonello, p. 4 dans la grande tradition de la fiction : que faire du romanesque et du genre (au cinéma) ? Comment, aujourd’hui, donner à éprouver un récit, un espace, un personnage, une émotion ? • Masterclass, p. 5 Aux prises résolument avec notre époque, faisant du temps, passé et présent, à la fois • Exposition, par Bertrand Bonello, p. 6 une matière, un instrument et une expérience, Le Pornographe, Tiresia, L’Apollonide et ses autres films travaillent le double et le genre, l’enfermement et la folie, l’engagement et le plaisir. • Livre, p. 10 Plus encore peut-être que la facture musicale et sonore de ses films, c’est probablement • Radio, p. 11 l’intelligence et le raffinement de leur construction, visant toujours la sensation et l’affect purs, • Bandes-son, par Bertrand Bonello, p. 12 qui donnent le mieux à percevoir le compositeur et musicien qu’est Bertrand Bonello. -

Paris Region at the 72 Cannes Film Festival

Paris Regionnd at the 72 Cannes PRESS PACK - MAYFilm 2019 Festival Paris Region Press contacts [email protected] +33 (0)1 53 85 63 14 [email protected] “Expanding our efforts to bolster creativity” gnès Varda described cinema as “a pas- Given that passion for cinema is passed on from sionate and dangerous experience”. a very early age, we have supplemented this The talented filmmakers nominated in strategy by bolstering art and culture education nd the official selections of the 72 Cannes for young people in Paris Region, by increasing the Film Festival certainly won’t be contradicting level of contact between these youth and the someone who was the first woman to receive a world of cinema – largely through film clubs in Palme d’honneur award. The passion is clear to see upper secondary schools and apprenticeship Aon every screen along the Croisette. But what a training centres, or by taking a mobile theatre to journey it is to finally feature on these famous our recreation parks over summer. screens! Recognising this, Paris Region stands The result of this strong, clear and genuine com- alongside the professionals involved throughout mitment of Paris Region to the cinema and audio- their perilous adventure of film-making. More than visual sector can be seen at events such as the ever before! It is the leading French region when it nd Cannes Film Festival. For this 72 edition, we are comes to supporting the cinema and audiovisual proud to once again be present via the high- sector and playing host to film shoots. -

House of Tolerance English Subtitles

House of tolerance english subtitles click here to download English www.doorway.ru, 1, amam. not perfect but tried to bring it close enough!!! English www.doorway.runceDVDRip, 1. English subtitle for House of Tolerance (House of Pleasures / L'Apollonide / Souvenirs de la maison close). Download House of Tolerance English YIFY YTS Subtitles. 0, English, Subtitle House of Tolerance AKA House of Pleasures dvdrip lpd, YTS. Download the popular multi language subtitles for House Of Tolerance Dvdrip. www.doorway.ru English. English subtitle (English subtitles). · www.doorway.ru English subtitle (English subtitles). L'Apollonide (Souvenirs. House Of Tolerance: {3} english (en) subtitles. Download and convert House of Tolerance movie subtitle in one of the following formats SRT. Download L'Apollonide (Souvenirs de la maison close) {(House of Tolerance AKA House of Pleasures)} subtitles. english subtitles. Watch online House of Tolerance full with English subtitle. Watch online free House of Tolerance, Hafsia Herzi, Jasmine Trinca, Noémie Lvovsky, Adèle. Download HOUSE OF TOLERANCE English Download subtitles. House of Pleasures - L'Apollonide: Souvenirs de la maison close Bertrand Bonello; ; France; French with English subtitles; 35mm; Life in an elegant Parisian brothel in the early twentieth century. The madam essentially owns the women: their. Full MOVIE Legit Link:: (www.doorway.ru) ▷▷ House of Tolerance FULL MOVIE House of Tolerance FULL MOVIE | House of. House of Tolerance (Souvenirs de la maison close) Duration: 2h5m; Country: France; Format: Digital; Year: ; Language: French with English subtitles. Find House of Tolerance [Region 2] [UK Import] at www.doorway.ru Movies & TV, Digital Stereo), English (Subtitles), ANAMORPHIC WIDESCREEN (). WITH ENGLISH SUBTITLES. -

Les Films Du Lendemain and My New Picture Present Dp Anglais 1/05/11 20:19 Page 2

dp anglais 1/05/11 20:19 Page 1 Les Films du Lendemain and My New Picture present dp anglais 1/05/11 20:19 Page 2 Les Films du Lendemain and My New Picture present WORLD SALES FILMS DISTRIBUTION 34 rue du Louvre 75001 Paris France Tél.: +33 1 53 10 33 99 Fax: +33 1 53 10 33 98 [email protected] www.filmsdistribution.com INTERNATIONAL PRESS RENDEZ-VOUS Viviana Andriani 25 fbg Saint Honoré 75008 Paris France Tél./Fax: +33 1 42 66 36 35 IN CANNES: +33 6 80 16 81 39 [email protected] 2011 France Color 2h05 35 mm 1.85 Dolby SRD www.rv-press.com FRENCH RELEASE: SEPTEMBER 21ST 2011 Photos and Press book to download from: www.rv-press.com dp anglais 1/05/11 20:19 Page 4 SYNOPSIS The dawn of the XXth century: L'Apollonide, a house of tolerance, is living its last days. In this closed world, where some men fall in love and others become viciously harmful, the girls share their secrets, their fears, their joys and their pains... dp anglais 1/05/11 20:19 Page 6 dp anglais 1/05/11 20:19 Page 8 CONVERSATION BETWEEN BERTRAND BONELLO AND LAURE ADLER1 Avril 2011 GENESIS LA: What is very interesting in your film is the specific role LAURE ADLER: How did the desire to make a movie about of the upstairs and the downstairs. The latter is a what was once called a house of tolerance come to you? sumptuous space, a beautiful background to enhance the beauty of the young women who are here to quench the BERTRAND BONELLO: Ten years ago, I wanted to make a sexual appetites of the bourgeois. -

Le Biopic : Comparaison De Deux Films

Rubrique « Meilleurs travaux étudiants » du département Carrières sociales de l’IUT de Paris Accueil de la page : <https://www.iut.parisdescartes.fr/metiers-du-social-socioculturel/meilleurs-travaux- etudiants-carrieres-sociales/> IUT PARIS DESCARTES – Département carrières sociales ASSC2 / Promo 2016-2017 Pratiques de créativité / cinéma / Patrick Pognant 1) Sujet LE BIOPIC : COMPARAISON DE DEUX FILMS CONTENU DU DOSSIER À RENDRE (GROUPES DE TROIS ÉTUDIANTS) YVES SAINT-LAURENT DE JALIL LESPERT (2014) : 101’ SAINT-LAURENT DE BERTRAND BONELLO (2014) : 144’ PARTIE COLLECTIVE (NOTÉE SUR 10) : TRAITEMENT OBJECTIF DES DONNÉES Fiche complète des deux films : le genre, réalisateur(s), scénariste(s), compositeur, produc- teur(s), casting, équipe technique, etc. (une à deux pages) ; restituer le synopsis des deux films (attention, un synopsis n’est pas une bande-annonce…) et définir les principaux per- sonnages (trois pages maxi) ; définir les points divergents et convergents entre les deux films par rapport à la biographie d’Yves Saint-Laurent mais aussi par rapport aux options de tournage, de montage, de la direction d’acteurs, de la bande son et des effets spéciaux éventuels. Cette partie collective du dossier est absolument objective (trois pages maxi). PARTIE INDIVIDUELLE (NOTÉE SUR 10) : PARTIE SUBJECTIVE 1) A) Développez succinctement votre point de vue critique sur chaque film. b) quelle est votre préférence et pourquoi ? c) la vie, somme toute romanesque d’Yves Saint-Lau- rent, méritait-elle deux biopics la même année ? (1 à 2 pages) ; 2) Que pensez-vous de la place accordée aux femmes dans les deux films (étayez vos propos par des exemples pris dans chacun des films) ? enfin, peut-on comprendre Yves Saint-Laurent, son parcours artistique, si l’on fait abstraction de son homosexualité ? (1 à 2 pages). -

All About Yves / Saint Laurent]

Document generated on 09/26/2021 1:35 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma All about Yves Saint Laurent Mathieu Séguin-Tétreault Number 294, January–February 2015 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/73391ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Séguin-Tétreault, M. (2015). Review of [All about Yves / Saint Laurent]. Séquences, (294), 16–17. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2015 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 16 LES FILMS | GROS PLAN Bertrand BONELLO Saint Laurent All about Yves À peine quelques mois après le prêt-à-filmer aseptisé Yves Saint Laurent de Jalil Lespert, Bertrand Bonello débarque avec Saint Laurent, (anti)biopic haut de gamme non autorisé, enivrant comme un parfum d’opium et enfiévré comme un chant d’amour et de mort. MATHIEU SÉGUIN-TÉTREAULT anse suave parée d’étoffes somptueuses, Saint Laurent démons mais aussi ceux de son époque, jouisseur torturé rongé se focalise sur une seule partie de la vie d’YSL : la décennie par la mélancolie, YSL apparaît avant tout comme un homme D1967-1976, la plus prospère et la plus obscure, la plus pétri de paradoxes, archétype d’une bourgeoisie décadente iconique et la plus sordide, celle que tout le monde connaît, avide d’expériences toujours plus extrêmes.