Plaster Monuments Architecture and the Power Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

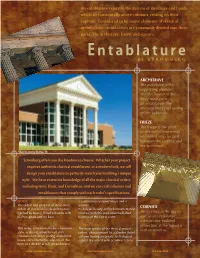

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

Materials & Process

Sculpture: Materials & Process Teaching Resource Developed by Molly Kysar 2001 Flora Street Dallas, TX 75201 Tel 214.242.5100 Fax 214.242.5155 NasherSculptureCenter.org INDEX INTRODUCTION 3 WORKS OF ART 4 BRONZE Material & Process 5-8 Auguste Rodin, Eve, 1881 9-10 George Segal, Rush Hour, 1983 11-13 PLASTER Material & Process 14-16 Henri Matisse, Madeleine I, 1901 17-18 Pablo Picasso, Head of a Woman (Fernande), 1909 19-20 STEEL Material & Process 21-22 Antony Gormley, Quantum Cloud XX (tornado), 2000 23-24 Mark di Suvero, Eviva Amore, 2001 24-25 GLOSSARY 26 RESOURCES 27 ALL IMAGES OF WORKS OF ART ARE PROTECTED UNDER COPYRIGHT. ANY USES OTHER THAN FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ARE STRICTLY FORBIDDEN. 2 Introduction This resource is designed to introduce students in 4th-12th grades to the materials and processes used in modern and traditional sculpture, specifically bronze, plaster, and steel. The featured sculptures, drawn from the collection of the Nasher Sculpture Center, range from 1881 to 2001 and represent only some of the many materials and processes used by artists whose works of art are in the collection. Images from this packet are also available in a PowerPoint presentation for use in the classroom, available at nashersculpturecenter.org. DISCUSS WITH YOUR STUDENTS Artists can use almost any material to create a work of art. When an artist is deciding which material to use, he or she may consider how that particular material will help express his or her ideas. Where have students seen bronze before? Olympic medals, statues… Plaster? Casts for broken bones, texture or decoration on walls.. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

Section 092400

SPEC MIX, Inc. – Guide Specification Note to User: This section contains macros to aid the editing process. By default Microsoft Word disables macros for virus security reasons. When you open a file that has macros, the yellow message bar appears with a shield icon and the enable content button. To enable these macros, click the Enable Content button. SECTION 09 24 00 PORTLAND CEMENT STUCCO (To View Hidden Text, Type CTRL-H) PART 1 – GENERAL 1.1 SECTION INCLUDES A. Portland Cement, Pre-blended Scratch and Brown Coat Stucco. B. Portland Cement, Pre-blended Fiber Base Coat Stucco. C. Portland Cement, Pre-blended Colored Finish Coat Stucco. 1.2 RELATED SECTIONS A. Section 03 30 00 - Cast-in-Place Concrete. B. Section 04 20 00 - Unit Masonry. C. Section 05 40 00 - Cold-Formed Metal Framing: Light gauge load-bearing metal framing. D. Section 06 10 00 - Rough Carpentry: Wood framing. E. Section 07 21 13 - Board Insulation. F. Section 07 92 00 - Joint Sealants. G. Section 09 22 16 - Non-Structural Metal Framing: Non-load-bearing metal framing systems. H. Section 09 22 36 - Metal Lath. I. Section 09 29 00 - Gypsum Board: Exterior gypsum sheathing. 1.3 REFERENCES A. American National Standards Institute (ANSI) / American Hardboard Association (AHA): 1. ANSI/AHA A 194 - Cellulosic Fiber Board. B. ASTM International (ASTM): 1. ASTM A 641/A 641M - Standard Specification for Zinc-Coated (Galvanized) Carbon Steel Wire. 2. ASTM A 653/A 653M - Standard Specification for Steel Sheet, Zinc-Coated (Galvanized) or Zinc- Iron Alloy-Coated (Galvannealed) by the Hot-Dip Process. -

Greek Columns in America

Greek Columns in America By: Sarah Griffin Doric Columns Doric columns are the simplest columns. The design is plain, but powerful-looking. The top is made of a circle topped by a square, and it does not have a base. The shaft is very plain, and it has 20 sides. It looked great on the long and rectangular buildings that the Greeks made. The frieze, which is the area above the column, has simple patterns. Above the columns, there are triglyphs and metopes. The metopes are plain and smooth. Doric Columns Continued The triglyphs have a patterns that has three vertical lines which are between the metopes. The order from bottom to top was the shaft, the capital, the architrave, the frieze, and the cornice. Doric Columns- Example #1 The State Capitol in Columbus, Ohio Doric Columns- Example #2 The Clark County Courthouse in Cleveland, Ohio Ionic Columns The shafts of the Ionic columns are taller than the shafts of Doric columns, which makes the columns look slender. They also had lines carved into them going from top to bottom, which were called flutes. The shafts had entasis, which is a bulge in the columns that make them look straight even at a distance. The frieze is plain. The bases are big and look like a set of stacked rings. The capitals have scrolls above the shaft. Ionic Columns Continued The Ionic columns are more decorative than the Doric columns. The order from bottom to top is the base, then the shaft, then the capital, then the architrave, then the frieze, then the cornice. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it. -

Traditional Architectural Renders on Earthen Surfaces

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1991 Traditional Architectural Renders on Earthen Surfaces Maria Isabel G. Beas University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Beas, Maria Isabel G., "Traditional Architectural Renders on Earthen Surfaces" (1991). Theses (Historic Preservation). 395. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/395 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Beas, Maria Isabel G. (1991). Traditional Architectural Renders on Earthen Surfaces. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/395 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Traditional Architectural Renders on Earthen Surfaces Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Beas, Maria Isabel G. (1991). Traditional Architectural Renders on Earthen Surfaces. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/395 'T,' i'&Sim mi> 'm m. i =ir,!t-i^-!vs i )'» \ •.'.i:'-ii-2\c-. fell ;;!•!' UNIVERSITVy PENNSYLVANIA. UBKARIES TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURAL RENDERS ON EARTHEN SURFACES Maria Isabel G. Beas A THESIS in The Graduate Program in Historic Presen/ation Presented to the faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 1991 Frank G.lMatero, Associate Professor 'reservation, Advisor X Samuel Y. -

Gypsum Resources of Iowa by Robert M

Gypsum Resources of Iowa by Robert M. McKay In mining gypsum at Fort Dodge, overlying glacial deposits are removed and the deeply creviced surface of the gypsum is exposed. These crevices resulted from movement of water along intersecting fractures in the easily eroded gypsum. Photo by Tim Kemmis. One of the softest minerals known to exist is the basis for one of Iowa's most durable mineral resource industries. Gypsum is a gray to white-colored mineral that can be easily scratched with a fingernail, and is referred to chemically as a hydrous calcium sulfate. Some of its other, perhaps more familiar, names are based on its various forms of occurrence. For example, alabaster is a massive form; satin spar is a fibrous variety; and selenite is its crystalline form. Gypsum often occurs in varying proportions with anhydrite (calcium sulfate), a slightly harder and more dense mineral that lacks water in its chemical make-up. Both gypsum and anhydrite belong to an interesting group of minerals called evaporites, which are sedimentary deposits composed of salts precipitated from sea water. Evaporites form in shallow or near shore marine and lake environments where evaporation has - 1 - produced an unusually high concentration of dissolved salts, and where there is little or no circulation of fresh water. The precipitation of sediment from these hypersaline brines is associated with hot and relatively dry climatic conditions. Iowa's paleogeography at several times in the state's geologic past duplicated these environments of deposition and resulted in major accumulations of evaporite minerals. As a result, several geologic units in Iowa's underlying sedimentary rock sequence host economically significant deposits of gypsum. -

Appendix E: Glossary

Appendix E: Glossary Appendix E Glossary Accessory Structure-A subordinate structure detached from but located on the same lot as a principle building. The use of an accessory structure must be identical and accessory to the use of the principle building. Accessory structures include garages, decks, and fences. Adaptive Use-Recycling an old building for a use other than that for which it was originally constructed. Addition - A non-original element placed onto an existing building, site or structure. Alteration - Any act or process that which the exterior architectural appearance of a building. Appropriate - Suitable to or compatible with what exists. Proposed work on historic properties is evaluated for "appropriateness" during the design review process. Architectural Style - Showing the influence of shapes, materials, detailing or other features associated with a particular architectural style. Ashlar-A dressed or squared stone and the masonry built of such hewn stone. It may be coursed, with continuous horizontal joints or random, with discontinuous joints. Baluster-A turned or rectangular upright supporting a stair handrail or forming part of a balustrade. Balustrade-An entire railing system including a top rail and its balusters, and often a bottom rail. Bay-One unit of a building that consists of a series of similar units; commonly defined as the number of vertical divisions within a building facade. Brace-A diagonal stabilizing member of a building frame. Bracket-A projecting support used under cornices, eaves, balconies, or windows to provide structural support. Capital-The uppermost part of a column or pilaster. E-1 Stone Mountain Design Guidelines Casement-A hinged window frame that opens horizontally like a door. -

Ancient Greek Architecture Complete the Graphic Organizer As You Follow Along with the Presentation

Ancient Greek Architecture Complete the graphic organizer as you follow along with the presentation. Types of Greek Columns • Doric • Ionic • Corinthian Doric Doric columns are the most simple of the three types of columns. There are three main parts of the column: the capitol, the shaft, and the frieze. The capitol is the top of the column that is made up of a circle topped by a square. The shaft is the tall part of the column. The frieze is the area above the column that has simple patterns for decorations. Doric Columns - Example There are many examples of ancient Doric buildings. Perhaps the most famous one is the Parthenon in Athens. Many buildings constructed today borrow some parts of the Doric design. Ionic The main parts of Ionic columns are the shaft, the flutes, the capitol, and the base. The shafts of Ionic columns are shorter than Doric columns, which made them look more slender. The flutes were lines that were carved into the shaft from top to bottom. The bases are large and look like carved, stacked rings. The capitols have scroll designs on them. The Ionic columns are a little more decorative than the Doric. Ionic Columns - Example • The Temple of Athena Nike in Athens, shown here, is one of the most famous Ionic buildings in the world. It is located on the Acropolis, very close to the Parthenon. Corinthian The Corinthian column is the most decorative column and is the type most people like best. The Corinthian capitals have flowers and leaves below a small scroll. -

Shale Gas Study

Foreign and Commonwealth Office Shale Gas Study Final Report April 2015 Amec Foster Wheeler Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited 2 © Amec Foster Wheeler Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited Report for Copyright and non-disclosure notice Tatiana Coutinho, Project Officer The contents and layout of this report are subject to copyright Setor de Embaixadas Sul owned by Amec Foster Wheeler (© Amec Foster Wheeler Foreign and Commonwealth Office Environment & Infrastructure UK Limited 2015). save to the Bririah Embassy extent that copyright has been legally assigned by us to Quadra 801, Conjunto K another party or is used by Amec Foster Wheeler under Brasilia, DF licence. To the extent that we own the copyright in this report, Brazil it may not be copied or used without our prior written agreement for any purpose other than the purpose indicated in this report. The methodology (if any) contained in this report is provided to you in confidence and must not be disclosed or Main contributors copied to third parties without the prior written agreement of Amec Foster Wheeler. Disclosure of that information may Pete Davis constitute an actionable breach of confidence or may Alex Melling otherwise prejudice our commercial interests. Any third party Daren Luscombe who obtains access to this report by any means will, in any Katherine Mason event, be subject to the Third Party Disclaimer set out below. Rob Deanwood Silvio Jablonski, ANP Third-party disclaimer Issued by Any disclosure of this report to a third party is subject to this disclaimer. The report was prepared by Amec Foster Wheeler at the instruction of, and for use by, our client named on the front of the report.