Ure Museum's Erasmus Internship Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and Was Thought of As the Personification of Cyclic Law, the Causal Power of Expansion, and the Angel of Miracles

Ζεύς The Angel of Cycles and Solutions will help us get back on track. In the old schools this angel was known as Jupiter (Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and was thought of as the personification of cyclic law, the Causal Power of expansion, and the angel of miracles. Price, John Randolph (2010-11-24). Angels Within Us: A Spiritual Guide to the Twenty-Two Angels That Govern Our Everyday Lives (p. 151). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Zeus 1 Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, justice [1] The Jupiter de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680 Abode Mount Olympus Symbol Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak Consort Hera and various others Parents Cronus and Rhea Siblings Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter Children Aeacus, Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Dardanus, Dionysus, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces [2] Roman equivalent Jupiter Zeus (Ancient Greek: Ζεύς, Zeús; Modern Greek: Δίας, Días; English pronunciation /ˈzjuːs/[3] or /ˈzuːs/) is the "Father of Gods and men" (πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε, patḕr andrōn te theōn te)[4] who rules the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father rules the family according to the ancient Greek religion. He is the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. Zeus is etymologically cognate with and, under Hellenic influence, became particularly closely identified with Roman Jupiter. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Aphrodite by Dione.[5] He is known for his erotic escapades. -

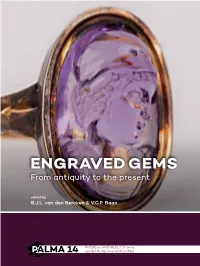

Engraved Gems

& Baan (eds) & Baan Bercken den Van ENGRAVED GEMS Many are no larger than a fingertip. They are engraved with symbols, magic spells and images of gods, animals and emperors. These stones were used for various purposes. The earliest ones served as seals for making impressions in soft materials. Later engraved gems were worn or carried as personal ornaments – usually rings, but sometimes talismans or amulets. The exquisite engraved designs were thought to imbue the gems with special powers. For example, the gods and rituals depicted on cylinder seals from Mesopotamia were thought to protect property and to lend force to agreements marked with the seals. This edited volume discusses some of the finest and most exceptional GEMS ENGRAVED precious and semi-precious stones from the collection of the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities – more than 5.800 engraved gems from the ancient Near East, Egypt, the classical world, renaissance and 17th- 20th centuries – and other special collections throughout Europe. Meet the people behind engraved gems: gem engravers, the people that used the gems, the people that re-used them and above all the gem collectors. This is the first major publication on engraved gems in the collection of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden since 1978. ENGRAVED GEMS From antiquity to the present edited by B.J.L. van den Bercken & V.C.P. Baan 14 ISBNSidestone 978-90-8890-505-6 Press Sidestone ISBN: 978-90-8890-505-6 PAPERS ON ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE LEIDEN MUSEUM OF ANTIQUITIES 9 789088 905056 PALMA 14 This is an Open Access publication. -

Plaster Monuments Architecture and the Power Of

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Monuments in Flux The absentminded visitor drifts by chance into the Hall of Architecture at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, where astonishment awaits. In part, the surprise is the sheer number of architectural fragments: Egyptian capitals, Assyrian pavements, Phoenician reliefs, Greek temple porches, Hellenistic columns, Etruscan urns, Roman entablatures, Gothic portals, Renaissance balconies, niches, and choir stalls; parapets and balustrades, sarcophagi, pulpits, and ornamental details. Center stage, a three-arched Romanesque church façade spans the entire width of the skylit gallery, colliding awkwardly into the surrounding peristyle. We find ourselves in a hypnotic space fabricated from reproduced building parts from widely various times and places. Cast from buildings still in use, from ruins, or from bits and pieces of architecture long since relocated to museums, the fragments present a condensed historical panorama. Decontextualized, dismembered, and with surfaces fashioned to imitate the patina of their referents, the casts convey a weird reality effect. Mute and ghostlike, they seem programmed to evoke the experience of the real thing. For me, the effect of this mimetic extravaganza only became more puzzling when I recognized— among chefs d’oeuvre such as a column from the Vesta temple at Tivoli, a portal from the cathedral in Bordeaux, and Lorenzo Ghiberti’s golden Gates of Paradise from the baptistery in Florence— a twelfth- century Norwegian stave- church portal. Impeccably document- ing the laboriously carved ornaments of the wooden church, it is mounted shoulder to shoulder with doorways from French and British medieval stone churches, the sequence materializing as three- dimensional wallpa- per. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Multifaceted Role Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Multifaceted Role of Plaster Casts in Contemporary Museums THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Art History by Alissa Ann Moyeda Thesis Committee: Professor Margaret M. Miles, Chair Professor Cecile Whiting Associate Professor Lyle Massey 2017 © 2017 Alissa Ann Moyeda DEDICATION To James and my sister Christina, who gave me endless support and love this past year at times when my anxieties and stress got the better of me. I could not have done this without you. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS v INTRODUCTION 1 Casts in Antiquity 2 Casts in the Renaissance 4 Casts in Nineteenth Century Europe 7 Casts in the United States 17 The Akropolis Museum and Its Casts 16 Lord Elgin's Actions in Greece 19 Attitudes in New Greece and Britain 21 Conclusion 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 31 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee chair, Professor Margaret M. Miles, for her great patience and assistance in my journey to write this thesis. It was thanks to her guidance that I was able to complete my writing. I would also like to thank my guidance counselor, Arielle Hinojosa-Garcia, for her encouragement and help. None of this would have been possible without her support and aid. Thank you to Associate Professor Roberta Wue and the other professors at UCI who made my time spent there more enjoyable and provided a safe and encouraging space to learn and grow. Lastly, a special thank you to all of the wonderful women in my program. -

Wandering Poets and the Dissemination of Greek Tragedy in the Fifth

Wandering Poets and the Dissemination of Greek Tragedy in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC Edmund Stewart Abstract This work is the first full-length study of the dissemination of Greek tragedy in the earliest period of the history of drama. In recent years, especially with the growth of reception studies, scholars have become increasingly interested in studying drama outside its fifth century Athenian performance context. As a result, it has become all the more important to establish both when and how tragedy first became popular across the Greek world. This study aims to provide detailed answers to these questions. In doing so, the thesis challenges the prevailing assumption that tragedy was, in its origins, an exclusively Athenian cultural product, and that its ‘export’ outside Attica only occurred at a later period. Instead, I argue that the dissemination of tragedy took place simultaneously with its development and growth at Athens. We will see, through an examination of both the material and literary evidence, that non-Athenian Greeks were aware of the works of Athenian tragedians from at least the first half of the fifth century. In order to explain how this came about, I suggest that tragic playwrights should be seen in the context of the ancient tradition of wandering poets, and that travel was a usual and even necessary part of a poet’s work. I consider the evidence for the travels of Athenian and non-Athenian poets, as well as actors, and examine their motives for travelling and their activities on the road. In doing so, I attempt to reconstruct, as far as possible, the circuit of festivals and patrons, on which both tragedians and other poetic professionals moved. -

The History and Antiquities of the Doric Race, Vol. 1 of 2 by Karl Otfried Müller

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The History and Antiquities of the Doric Race, Vol. 1 of 2 by Karl Otfried Müller This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The History and Antiquities of the Doric Race, Vol. 1 of 2 Author: Karl Otfried Müller Release Date: September 17, 2010 [Ebook 33743] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF THE DORIC RACE, VOL. 1 OF 2*** The History and Antiquities Of The Doric Race by Karl Otfried Müller Professor in the University of Göttingen Translated From the German by Henry Tufnell, Esq. And George Cornewall Lewis, Esq., A.M. Student of Christ Church. Second Edition, Revised. Vol. I London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. 1839. Contents Extract From The Translators' Preface To The First Edition.2 Advertisement To The Second Edition. .5 Introduction. .6 Book I. History Of The Doric Race, From The Earliest Times To The End Of The Peloponnesian War. 22 Chapter I. 22 Chapter II. 39 Chapter III. 50 Chapter IV. 70 Chapter V. 83 Chapter VI. 105 Chapter VII. 132 Chapter VIII. 163 Chapter IX. 181 Book II. Religion And Mythology Of The Dorians. 202 Chapter I. 202 Chapter II. 216 Chapter III. 244 Chapter IV. 261 Chapter V. 270 Chapter VI. 278 Chapter VII. 292 Chapter VIII. 302 Chapter IX. -

Wandering Poets and the Dissemination of Greek Tragedy in the Fifth

Wandering Poets and the Dissemination of Greek Tragedy in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC Edmund Stewart Abstract This work is the first full-length study of the dissemination of Greek tragedy in the earliest period of the history of drama. In recent years, especially with the growth of reception studies, scholars have become increasingly interested in studying drama outside its fifth century Athenian performance context. As a result, it has become all the more important to establish both when and how tragedy first became popular across the Greek world. This study aims to provide detailed answers to these questions. In doing so, the thesis challenges the prevailing assumption that tragedy was, in its origins, an exclusively Athenian cultural product, and that its „export‟ outside Attica only occurred at a later period. Instead, I argue that the dissemination of tragedy took place simultaneously with its development and growth at Athens. We will see, through an examination of both the material and literary evidence, that non-Athenian Greeks were aware of the works of Athenian tragedians from at least the first half of the fifth century. In order to explain how this came about, I suggest that tragic playwrights should be seen in the context of the ancient tradition of wandering poets, and that travel was a usual and even necessary part of a poet‟s work. I consider the evidence for the travels of Athenian and non-Athenian poets, as well as actors, and examine their motives for travelling and their activities on the road. In doing so, I attempt to reconstruct, as far as possible, the circuit of festivals and patrons, on which both tragedians and other poetic professionals moved. -

The History of Phoenicia by George Rawlinson

THE HISTORY OF PHOENICIA BY GEORGE RAWLINSON The first half of this history of the Phoenicians covers the land, art, industry, cities, commerce, and religion of the Canaanites people. The second half covers their political history from about 1200 B.C. to 600 A.D. Of particular interest are chapters on colonies, commerce, religion and history of Phoenicia and Carthage. Overall, the book emphasizes the positive contributions of Phoenicia rather than dwelling on some of the more despicable aspects of its religious rites and commercial enterprises. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE LAND ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 CLIMATE AND PRODUCTIONS ........................................................................................................................ 17 THE PEOPLE—ORIGIN AND CHARACTERISTICS .......................................................................................... 24 THE CITIES ..................................................................................................................................................... 31 THE COLONIES .............................................................................................................................................. 41 ARCHITECTURE.............................................................................................................................................. 58 AESTHETIC ART ............................................................................................................................................ -

The Sons of Jacob and the Sons of Herakles: Myth, Genealogy, and the Construction of Identity

THE SONS OF JACOB AND THE SONS OF HERAKLES: MYTH, GENEALOGY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY BY ANDREW TOBOLOWSKY B.A., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2007 M.PHIL, TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN, 2008 M.A., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2011 Ph.D., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2015 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Andrew B. Tobolowsky This dissertation by Andrew Tobolowsky is accepted in its present form by the Department of Religious Studies as satisfying the Dissertation Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date_________ ----------------------------- Saul Olyan, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date_________ ----------------------------- Stanley Stowers, Reader Date_________ ----------------------------- Pura Nieto Hernandez, Reader Approved by Graduate Council Date_________ ----------------------------- Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Andrew Tobolowsky was born April 17th, 1985. He attended Brown University as an undergraduate, receiving a B.A. in Religious Studies in 2007. Subsequently, he attended Trinity College, Dublin, where he received an M.Phil in Literature, which he used to teach literature in various ways in Dallas, Texas. He began his PhD at Brown in the fall of 2009 and received an M.A. in 2011. He has taught classes in biblical Hebrew and World Literature and assisted in classes ranging from Greek Myth, to Modern Problems of Belief, to Introductions to Islam and Biblical Literature. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been completed without the constant support of my friends and family. It would have been much less than it is without the tireless work of my advisers, especially Saul Olyan, but Stanley Stowers and Pura Nieto Hernandez very much as well. -

Gods, Ghosts and Newlyweds: Exploring the Uses of the Threshold in Greek A

GODS, GHOSTS AND NEWLYWEDS: EXPLORING THE USES OF THE THRESHOLD IN GREEK AND ROMAN SUPERSTITION AND FOLKLORE by DEBORAH MARY KERR A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of CLassics, Ancient History and ArchaeoLogy CoLLege of Arts and Law University of Birmingham August 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This is the first reappraisaL of the supernaturaL symboLism of the threshoLd in over a century. This thesis wilL chaLLenge the notion that this LiminaL Location was significant in Greek and Roman superstition and foLkLore – from apotropaic devices appLied to the door, to Lifting the bride over the threshold – because it was believed to be haunted by ghosts. In Part One, this thesis examines the evidence of prophyLactic devices and magic speLLs used at the threshoLd, aLong with the potentiaL for human buriaL under the doorway, and concludes that there is no evidence for such a belief. However, this thesis does find evidence for a beLief in the haunting of ghosts at the equaLLy LiminaL Location of the crossroads. -

Arrian Notes

ARIAN 1 Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μέγας A SYNOPSIS OF "Arrian The Campaigns of Alexander The Great" (356 -323 BC) CONTENTS Autumn 336 - Winter 334 | Europe and Western Asia 4 THE NORTHERN CAMPAIGNS! 5 THEBES 9 THE BATTLE OF THE RIVER GRANICUS - Spring 334 BC 11 Leaving Cert Question 2000! 14 THE RESTORATION OF DEMOCRACIES | ALONG THE AEGEAN SEABOARD! 19 The Costal Campaigns! 19 Miletus! 19 Leaving Cert Question 1998 20 Halicarnassus! 20 The Gordian Knot! 22 2 3 AUTUMN 336 - WINTER 334 | EUROPE AND WESTERN ASIA Autumn 336 MACEDONIA Philip II is assassinated, Alexander becomes king. Spring 335 NORTHERN CAMPAIGNS Alexander puts down revolts of subject peoples. DANUBE Alexander crosses the river, defeats Getae. DANUBE Triballoi offer surrender; Celts send envoys. ILLYRIA Rebellious Taulantians and other Illyrians are subdued. GREECE Alexander destroys Thebes, receives submission of major Greek cities with the exception of Sparta. Spring 334 HELLESPONT Alexander leads his army into Asia and visits Troy. GRANICUS The Macedonian army defeats Persian forces led by western satraps. Summer 334 WESTERN ASIA Alexander takes control of Sardis and Ephesus. THE SIEGE OF MILETUS Alexander takes Miletus by siege and disbands most of his navy. HALICARNASSUS Halicarnassus is captured, except for its citadel. Autumn 334 CARIA-LYCIA A l e x a n d e r a r r a n g e s n e w administrators, sends for new recruits. Winter 334/3 LYCIA Cities of Lycia surrender to Alexander. 4 THE NORTHERN CAMPAIGNS On Alexander’s succession to the throne, he assembled all Greeks in Peloponnese and asked for the command of the campaign against Persia, which had been previously granted to his late father Philip of Macedonia. -

Cast Contemporaries

CAST CONTEMPORARIES I notice that in the most cutting-edge art schools today – the ones that also happen to have large holdings of plaster-casts of the works of antiquity, medieval art and renaissance masterpieces – there is usually at least one tutor or person in authority who is keen to protest an “interest” in the works of past time as represented in these copies. But the political situation instituted during the contemporist clampdown of the last century means that these people have to conceal their obvious enthusiasm for these works behind a critical mask. These plasters are, they insist, of “historical interest” – or they have an “identity”, or they represent a “casting aesthetic all their own,” and so on. In this way these responsible people make a claim for the plaster-cast’s being tolerated within the contemporary art school setting, where powerful and visceral antipathies to the grand manner of Occidental art persist. The lovers of the plaster-cast recognise the danger which daily threatens the plaster cast and so encourage the cast collections (a) to be studiously museologised under the rubric of art-conservation, and (b) to be employed within the context of contemporist artistic idioms. In this way the casts are removed from their rough life of pedagogical function (in which they once thrived) while being purloined by talentless and lazy art- students as “found objects” arranged without leave within “installations” which pretend to base their meanings upon “issues.” I was assured, once, by one such guardian, that were the casts not seen to be exploited in this contrary way then they should be “out, out, out!” He made a throat-cutting gesture as he said this to me.