Cast Contemporaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Peter Davidson Collection of Ian Hamilton Finlay MSS.013 Finding Aid Prepared by Ryan Evans; Collection Processed by Ryan Evans

CCS Bard Archives Phone: 845.758.7567 Center for Curatorial Studies Fax: 845.758.2442 Bard College Email: [email protected] Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504 Guide to the Peter Davidson Collection of Ian Hamilton Finlay MSS.013 Finding aid prepared by Ryan Evans; Collection processed by Ryan Evans. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit April 29, 2016 Guide to the Peter Davidson Collection of Ian Hamilton Finlay MSS. Table of Contents Summary Information..................................................................................................................................3 Biographical/Historical note.........................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note........................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information...........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings.......................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory.....................................................................................................................................7 -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Allan Ramsay, ‘Verses by the Celebrated Allan Ramsay to his Son. On his Drawing a Fine Gentleman’s Picture’, in The Scarborough Miscellany for the Year 1732, 2nd edn (London: Wilford, 1734), pp. 20–22 (p. 20, p. 21, p. 21). 2. See Iain Gordon Brown, Poet & Painter, Allan Ramsay, Father and Son, 1684–1784 (Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland, 1984). 3. When considering works produced prior to the formation of the United Kingdom in 1801, I have followed in this study the eighteenth-century prac- tice of using ‘united kingdom’ in lower case as a synonym for Great Britain. 4. See, respectively, Kurt Wittig, The Scottish Tradition in Literature (London: Oliver and Boyd, 1958); G. Gregory Smith, Scottish Literature: Character and Influence (London: Macmillan, 1919); Hugh MacDiarmid, A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, ed. by Kenneth Buthlay (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1988); David Craig, Scottish Literature and the Scottish People, 1680–1830 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1961); David Daiches, The Paradox of Scottish Culture: The Eighteenth-Century Experience (London: Oxford University Press, 1964); Kenneth Simpson, The Protean Scot: The Crisis of Identity in Eighteenth-Century Scottish Literature (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1988); Robert Crawford, Devolving English Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992); Murray Pittock, Poetry and Jacobite Politics in Eighteenth- Century Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994) and idem, Scottish and Irish Romanticism (Oxford: Oxford University -

Ossian: Past Present and Future Mitchell, Sebastian

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Ossian: Past Present and Future Mitchell, Sebastian License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Mitchell, S 2016, 'Ossian: Past Present and Future', Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 39, no. 2. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 08/03/2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Ure Museum's Erasmus Internship Report

Ure Museum’s Erasmus Internship Report Beirão2014 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS HISTÓRIA ANTIGA The Ure Museum’s Internship - Erasmus Report Mariana Gomes Beirão Mestrado em História- História Antiga 2014 1 Ure Museum’s Erasmus Internship Report Beirão2014 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS HISTÓRIA ANTIGA The Ure Museum’s Internship Erasmus Report Mariana Gomes Beirão Mestrado em História- História Antiga Orientação: Prof. Doutor Amílcar Guerra 2014 2 Ure Museum’s Erasmus Internship Report Beirão2014 Agradecimentos Queria agradecer em primeiro lugar à Assistente da Curadora Guja Bandini e à Curadora Prof. Amy Smith por me terem proporcionado um óptimo estágio. Ambas foram formidáveis, adorei os meus três meses a trabalhar no Ure Museum of Greek Archeology. Em segundo lugar à Universidade de Reading por ter facilitado o meu alojamento pertíssimo do campus ao ponto de poder ir a pé todos os dias para o museu, um muito obrigado. Em terceiro lugar queria agradecer a três grandes amigos; ao Dr. Nick West por ter feito a tradução dos escaravelhos egípcios graças ao seu vasto conhecimento sobre o Antigo Egipto; ao Eduardo Ganilho, pelas fantásticas traduções de Grego, um muitíssimo obrigado (és um génio!); ao estupendo artista André Batista pelo desenho no Paddle Text da Maquilhagem Egípcia, OBRIGADO A TODOS! Por último, um agradecimento especial ao meu orientador, o Professor Amílcar Guerra por ter autorizado a minha ida em Erasmus e por toda a ajuda que prestou. 3 Ure Museum’s Erasmus Internship Report Beirão2014 Resumo A exposição seguinte consiste no relatório de estágio Erasmus decorrido de Setembro de 2014 a Dezembro de 2014 no The Ure Museum of Greek Archeology em Reading, Inglaterra. -

Promise, Demonstrating a Fruitful Marriage Between History, Heritage

REVIEWS 327 promise, demonstrating a fruitful marriage From 1987 to 1992 Simpson prepared between history, heritage and science. designs for Paternoster Square, City of London, to replace the dismally grim work (1956)of William Graham Holford (1907–75), who airily AUDREY MTHORSTAD and arrogantly declared he wanted ‘no harmony of scale, character, or placing, just a total con- trast’, and deliberately obliterated all traces of earlier street-patterns. Although Simpson’s work was never realised, it has been influential in that doi:10.1017⁄s0003581517000191 it shows a humane and beautiful alternative to the kind of Dystopian dreariness that was de The Architecture of John Simpson: the timeless rigueur when Holford’sinflated reputation — — language of classicism.ByDAVID WATKIN. which did not long survive him unaccountably 330mm. Pp 304, many ills, chiefly col. Rizzoli dazzled his contemporaries (Nikolaus Pevsner International Publications, New York, 2016. ( 1902–83), in The Buildings of England (1973) ’ ’ ISBN 9780847848690.£55 (hbk). called Holford s work near St Paul s Cathedral an ‘outstandingly well conceived precinct’, John Anthony Simpson (b 1954) has established which it patently was not, and it barely lasted himself as an architectural practitioner of what twenty years). has become known as New Classicism, drawing Other important works were Simpson’s on a rich and infinitely adaptable architectural designs for Poundbury, Dorset, including the language that was deliberately discarded by Market Hall (2000); substantial interventions at Modernists in favour of a poverty-stricken Kensington Palace (including the delightfully pidgin (in linguistic terms, the equivalent of delicate cast-iron loggia forming the new garden- monosyllabic grunts), the appalling failures of entrance to the building); buildings at Lady which are obvious to all those not blinded Margaret Hall, Oxford, including remarkable by their beliefs in a destructive cult. -

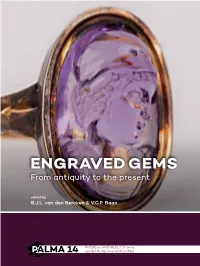

Engraved Gems

& Baan (eds) & Baan Bercken den Van ENGRAVED GEMS Many are no larger than a fingertip. They are engraved with symbols, magic spells and images of gods, animals and emperors. These stones were used for various purposes. The earliest ones served as seals for making impressions in soft materials. Later engraved gems were worn or carried as personal ornaments – usually rings, but sometimes talismans or amulets. The exquisite engraved designs were thought to imbue the gems with special powers. For example, the gods and rituals depicted on cylinder seals from Mesopotamia were thought to protect property and to lend force to agreements marked with the seals. This edited volume discusses some of the finest and most exceptional GEMS ENGRAVED precious and semi-precious stones from the collection of the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities – more than 5.800 engraved gems from the ancient Near East, Egypt, the classical world, renaissance and 17th- 20th centuries – and other special collections throughout Europe. Meet the people behind engraved gems: gem engravers, the people that used the gems, the people that re-used them and above all the gem collectors. This is the first major publication on engraved gems in the collection of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden since 1978. ENGRAVED GEMS From antiquity to the present edited by B.J.L. van den Bercken & V.C.P. Baan 14 ISBNSidestone 978-90-8890-505-6 Press Sidestone ISBN: 978-90-8890-505-6 PAPERS ON ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE LEIDEN MUSEUM OF ANTIQUITIES 9 789088 905056 PALMA 14 This is an Open Access publication. -

Plaster Monuments Architecture and the Power Of

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction Monuments in Flux The absentminded visitor drifts by chance into the Hall of Architecture at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, where astonishment awaits. In part, the surprise is the sheer number of architectural fragments: Egyptian capitals, Assyrian pavements, Phoenician reliefs, Greek temple porches, Hellenistic columns, Etruscan urns, Roman entablatures, Gothic portals, Renaissance balconies, niches, and choir stalls; parapets and balustrades, sarcophagi, pulpits, and ornamental details. Center stage, a three-arched Romanesque church façade spans the entire width of the skylit gallery, colliding awkwardly into the surrounding peristyle. We find ourselves in a hypnotic space fabricated from reproduced building parts from widely various times and places. Cast from buildings still in use, from ruins, or from bits and pieces of architecture long since relocated to museums, the fragments present a condensed historical panorama. Decontextualized, dismembered, and with surfaces fashioned to imitate the patina of their referents, the casts convey a weird reality effect. Mute and ghostlike, they seem programmed to evoke the experience of the real thing. For me, the effect of this mimetic extravaganza only became more puzzling when I recognized— among chefs d’oeuvre such as a column from the Vesta temple at Tivoli, a portal from the cathedral in Bordeaux, and Lorenzo Ghiberti’s golden Gates of Paradise from the baptistery in Florence— a twelfth- century Norwegian stave- church portal. Impeccably document- ing the laboriously carved ornaments of the wooden church, it is mounted shoulder to shoulder with doorways from French and British medieval stone churches, the sequence materializing as three- dimensional wallpa- per. -

Annual Review 2013–2014 the National Galleries of Scotland Cares For, Develops, Researches and Displays the National Collection of Scottish

Annual Review 2013–2014 The National Galleries of Scotland cares for, develops, researches and displays the national collection of Scottish © Keith Hunter Photography © Andrew Lee © Keith Hunter Photography and international fine art and, Scottish National Gallery Scottish National Portrait Gallery Scottish National Gallery with a lively and innovative The Scottish National Gallery comprises The Scottish National Portrait Gallery of Modern Art One three linked buildings at the foot of is about the people of Scotland – past Home to Scotland’s outstanding national programme of exhibitions, the Mound in Edinburgh. The Gallery and present, famous or forgotten. The collection of modern and contemporary education and publications, houses the national collection of fine portraits are windows into their lives art, the Scottish National Gallery of art from the early Renaissance to the and the displays throughout the beautiful Modern Art comprises two buildings, aims to engage, inform end of the nineteenth century, including Arts and Crafts building help explain Modern One and Modern Two. The early the national collection of Scottish art how the men and women of earlier times part of the collection features French and inspire the broadest from around 1600 to 1900. The Gallery made Scotland the country it is today. and Russian art from the beginning of possible public. is joined to the Royal Scottish Academy Photography and film also form part of the twentieth century, cubist paintings building via the underground Weston the collection and help to make Scotland’s and superb holdings of Expressionist and Link, which contains a restaurant, café, colourful history come alive. modern British art. -

James Clerk Maxwell Statue DONORS

James Clerk Maxwell Statue DONORS James Clerk Maxwell Statue DONORS ames Clerk Maxwell is generally regarded as the greatest physicist after Newton. While Newton laid down the laws of mechanics and Juniversal gravitation, Maxwell did the same for electromagnetism, showing in particular that light was part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Our modern technological society, from the computer to telecommunications, rests firmly on the foundations established by Maxwell. Albert Einstein was one of Maxwell’s great admirers and it was Maxwell’s emphasis on the basic role of fields of force that led Einstein to his general theory of relativity and the modern understanding of gravity. Born in Edinburgh in 1831, Maxwell was educated locally before moving to Cambridge, where he became a Fellow of Trinity. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1856 at the age of 24, and of the Royal Society in London in 1859. After holding chairs at Aberdeen and King’s College, London, he retired to his family estate at Glenlair in Dumfriesshire, where he wrote his great treatise on electricity and magnetism. In 1871, he returned to Cambridge and established the Cavendish Laboratory. Sadly, Maxwell died at the early age of 48. 1 For a scientist of Maxwell’s stature, there are few memorials to him. In 2006, the 175th anniversary of his birth, the Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE), led by its then President Sir Michael Atiyah, initiated plans for a statue, which culminated in its unveiling in George Street on 25 November 2008. The statue would not have been possible without the donations of many who wished to recognise James Clerk Maxwell’s achievements and legacy. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Multifaceted Role Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Multifaceted Role of Plaster Casts in Contemporary Museums THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Art History by Alissa Ann Moyeda Thesis Committee: Professor Margaret M. Miles, Chair Professor Cecile Whiting Associate Professor Lyle Massey 2017 © 2017 Alissa Ann Moyeda DEDICATION To James and my sister Christina, who gave me endless support and love this past year at times when my anxieties and stress got the better of me. I could not have done this without you. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS v INTRODUCTION 1 Casts in Antiquity 2 Casts in the Renaissance 4 Casts in Nineteenth Century Europe 7 Casts in the United States 17 The Akropolis Museum and Its Casts 16 Lord Elgin's Actions in Greece 19 Attitudes in New Greece and Britain 21 Conclusion 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 31 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee chair, Professor Margaret M. Miles, for her great patience and assistance in my journey to write this thesis. It was thanks to her guidance that I was able to complete my writing. I would also like to thank my guidance counselor, Arielle Hinojosa-Garcia, for her encouragement and help. None of this would have been possible without her support and aid. Thank you to Associate Professor Roberta Wue and the other professors at UCI who made my time spent there more enjoyable and provided a safe and encouraging space to learn and grow. Lastly, a special thank you to all of the wonderful women in my program. -

Why Beauty Matters/Perché La Bellezza Ha Importanza, Di Roger Scruton

Why Beauty Matters/Perché la bellezza ha importanza, di Roger Scruton - Scritto da Redazione de Gliscritti: 26 /01 /2020 - 14:37 pm Riprendiamo dal sito Gliscritti.it la trascrizione delle parole di un documentario di Roger Scruton per la BBC con l’introduzione che accompagnava la trascrizione sul sito stesso. Restiamo a disposizione per l’immediata rimozione se la sua presenza sul nostro sito non fosse gradita a qualcuno degli aventi diritto. Il Centro culturale Gli scritti (26/1/2020) Nei mesi di novembre e di dicembre del 2009, il secondo e il quarto canale della BBC. British Broadcasting Corporation, la società radiotelevisiva pubblica del Regno Unito, hanno mandato in onda un ciclo di documentari dal titolo Modern Beauty, che intendeva esaminare la percezione della bellezza nelle forme artistiche classiche e moderne. Il quinto della serie, intitolato Why Beauty Matters, diretto da Louise Lockwood e mandato in onda la prima volta il 28-11-2009, è stato affidato allo scrittore e filosofo britannico Roger Scruton. Nato nel 1944, Scruton si è laureato a Cambridge nel 1965 e ha insegnato Estetica al Birkbeck College dell’Università di Londra dal 1971 al 1992. Fondatore nel 1982 del trimestrale The SalisburyReview, lo ha diretto fino al 2000. Insegna attualmente presso l’università di St. Andrews in Scozia ed è visiting scholar dell’American Enterprise Institute a Washington. Con l’autorizzazione dell’autore pubblichiamo il testo di Why Beauty Matters. La traduzione — che riduce le ripetizioni tipiche dello stile parlato —, la suddivisione in paragrafi, le inserzioni fra parentesi quadre e le note sono redazionali. -

Graeme Moore Collection of Ian Hamilton Finlay Material Ms

Graeme Moore collection of Ian Hamilton Finlay material Ms. Coll. 1386 Finding aid prepared by Sam Allingham. Last updated on April 15, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2019 April 8 Graeme Moore collection of Ian Hamilton Finlay material Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 Series I: Correspondence.........................................................................................................................8 Series