The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

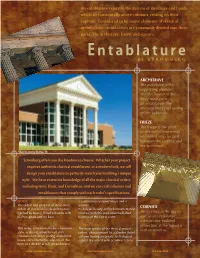

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

The Conversion of the Parthenon Into a Church: the Tübingen Theosophy

The Conversion of the Parthenon into a Church: The Tübingen Theosophy Cyril MANGO Δελτίον XAE 18 (1995), Περίοδος Δ'• Σελ. 201-203 ΑΘΗΝΑ 1995 Cyril Mango THE CONVERSION OF THE PARTHENON INTO A CHURCH: THE TÜBINGEN THEOSOPHY Iveaders of this journal do not have to be reminded of the sayings "of a certain Hystaspes, king of the Persians the uncertainty that surrounds the conversion of the or the Chaldaeans, a very pious man (as he claims) and for Parthenon into a Christian church. Surprisingly to our that reason deemed worthy of receiving a revelation of eyes, this symbolic event appears to have gone entirely divine mysteries concerning the Saviour's incarnation"5. unrecorded. The only piece of written evidence that has At the end of the work was placed a very brief chronicle been adduced concerns the removal of Athena's cult (perhaps simply a chronology) from Adam to the emperor statue, mentioned without a firm date in Marinus' Life of Zeno (474-91), in which the author advanced the view that Proclus (written in 485/6, the year following the the world would end in the year 6000 from Creation. philosopher's death)1. It is not clear, however, whether The original work was, therefore, composed between this removal marked the conversion of the building to 474 and, at the latest, 508, assuming the author was using Christian worship or merely its desacralization. The two, the Alexandrian computation from 5492 BC. The we have been told, need not have been simultaneous and expectation that the world would end in the reign of it is not inconceivable that the Parthenon remained Anastasius was, indeed, quite widespread at the time6. -

1 Mystery Cults and Visual Language in Graeco-Roman Antiquity: an Introduction

1 Mystery Cults and Visual Language in Graeco-Roman Antiquity: An Introduction Nicole Belayche and Francesco Massa Like the attendants at the rites, who stand outside at the doors […] but never pass within. Dio Chrysostomus … Behold, I have related things about which you must remain in igno- rance, though you have heard them. Apuleius1 ∵ These two passages from two authors, one writing in Greek, the other in Latin, set the stage of this book on Mystery cults in Visual Representation in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. In this introductory chapter we begin with a broad and problematiz- ing overview of mystery cults, stressing the original features of “mysteries” in the Graeco-Roman world – as is to be expected in this collection, and as is necessary when dealing with this complex phenomenon. Thereafter we will address our specific question: the visual language surrounding the mysteries. It is a complex and daunting challenge to search for ancient mysteries,2 whether represented textually or visually, whether we are interested in their 1 Dio Chrysostomus, Discourses, 36, 33: ὅμοιον εἶναι τοῖς ἔξω περὶ θύρας ὑπηρέταις τῶν τελετῶν […] οὐδέ ποτ’ ἔνδον παριοῦσιν (transl. LCL slightly modified); Apuleius, Metamorphoses, 11, 23: Ecce tibi rettuli, quae, quamvis audita, ignores tamen necesse est (transl. J. Gwyn Griffiths, Apuleius of Madauros, The Isis-Book (Metamorphoses, book XI) (Leiden, Brill: 1975), 99). 2 Thus the program (2014–2018) developed at the research center AnHiMA (UMR 8210, Paris) on “Mystery Cults and their Specific Ritual Agents”, in collaboration with the programs “Ambizione” and “Eccellenza”, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and hosted by the University of Geneva (2015–2018) and University of Fribourg (2019–2023). -

Mark Scheme for June 2018

GCE Classics: Classical Civilisation Unit F388: Art and Architecture in the Greek World Advanced GCE Mark Scheme for June 2018 Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations OCR (Oxford Cambridge and RSA) is a leading UK awarding body, providing a wide range of qualifications to meet the needs of candidates of all ages and abilities. OCR qualifications include AS/A Levels, Diplomas, GCSEs, Cambridge Nationals, Cambridge Technicals, Functional Skills, Key Skills, Entry Level qualifications, NVQs and vocational qualifications in areas such as IT, business, languages, teaching/training, administration and secretarial skills. It is also responsible for developing new specifications to meet national requirements and the needs of students and teachers. OCR is a not-for-profit organisation; any surplus made is invested back into the establishment to help towards the development of qualifications and support, which keep pace with the changing needs of today’s society. This mark scheme is published as an aid to teachers and students, to indicate the requirements of the examination. It shows the basis on which marks were awarded by examiners. It does not indicate the details of the discussions which took place at an examiners’ meeting before marking commenced. All examiners are instructed that alternative correct answers and unexpected approaches in candidates’ scripts must be given marks that fairly reflect the relevant knowledge and skills demonstrated. Mark schemes should be read in conjunction with the published question papers and the report on the examination. © OCR 2018 F388 Mark Scheme June 2018 SUBJECT SPECIFIC MARKING INSTRUCTIONS These are the annotations, (including abbreviations), including those used in RM Assessor, which are used when marking Annotation Meaning of annotation Blank Page – this annotation must be used on all blank pages within an answer booklet and on each page of an additional object where there is no candidate response. -

The Athenian Agora

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 12 Prepared by Dorothy Burr Thompson Produced by The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vermont American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993 ISBN 87661-635-x EXCAVATIONS OF THE ATHENIAN AGORA PICTURE BOOKS I. Pots and Pans of Classical Athens (1959) 2. The Stoa ofAttalos II in Athens (revised 1992) 3. Miniature Sculpturefrom the Athenian Agora (1959) 4. The Athenian Citizen (revised 1987) 5. Ancient Portraitsfrom the Athenian Agora (1963) 6. Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade (revised 1979) 7. The Middle Ages in the Athenian Agora (1961) 8. Garden Lore of Ancient Athens (1963) 9. Lampsfrom the Athenian Agora (1964) 10. Inscriptionsfrom the Athenian Agora (1966) I I. Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (1968) 12. An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora (revised 1993) I 3. Early Burialsfrom the Agora Cemeteries (I 973) 14. Graffiti in the Athenian Agora (revised 1988) I 5. Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora (1975) 16. The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (revised 1986) French, German, and Greek editions 17. Socrates in the Agora (1978) 18. Mediaeval and Modern Coins in the Athenian Agora (1978) 19. Gods and Heroes in the Athenian Agora (1980) 20. Bronzeworkers in the Athenian Agora (1982) 21. Ancient Athenian Building Methods (1984) 22. Birds ofthe Athenian Agora (1985) These booklets are obtainable from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens c/o Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. 08540, U.S.A They are also available in the Agora Museum, Stoa of Attalos, Athens Cover: Slaves carrying a Spitted Cake from Market. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

CLIL Multikey Lesson Plan LESSON PLAN

CLIL MultiKey lesson plan LESSON PLAN Subject: Art History Topic: The Athenian acropolis Students' age: 14-15 Language level: B1 Time: 2 hours Content aims: Art History (and a bit of History) on ancient Greece and the poleis. To describe an artistic element of an ancient city To understand the political role of Art and Religion in Ancient Greece Language aims: - Listening activity - Learn and use new vocabulary - Knowledge of technical art and history vocabulary Pre-requisites: - Geographical and cartographical skill - Knowledge of Greek history from the Persian wars to Pericles; - The role of the city in the world Materials: - Personal computer - handouts Procedure steps: Teacher starts explaining the geographical asset: where is Greece in Europe, where is Athens, arriving to the map that shows the metropolis in the details. Then after a short brainstorming activity about the poleis, (birth and main characters) arrives to the substantial continuity of the word polis in English. Which are the words deriving from polis? acropolis, necropolis, metropolis, metropolitan; megalopolis, cosmopolitan; Politics Policy Police T. shows map and asks: 1 CLIL MultiKey lesson plan Where are the acropolis and the necropolis of Athens? Then t. shows a video, inviting students to understanding the following items: - Which was the Athenian political role? - Which politicians are quoted? Why? When do they live? - Which are the most relevant urban changes for Athens? Finally teacher invites students to complete the handout 2 CLIL MultiKey lesson plan HANDOUT a) Sites references: Image coins: http://www.ancientresource.com/lots/greek/coins_athens.html http://blogs-images.forbes.com/stephenpope/files/2011/05/300px-1_euro_coin_Gr_serie_1.png Athena's birth: http://galeri7.uludagsozluk.com/282/zeus_454246.png b) vvideos's transcripts 1) https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/greek-art/classical/v/parthenon Transcript Voiceover: We're looking at the Parthenon. -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna. -

The Pedestal of the Athena Promachos 109

THE PEDESTALOF THE ATHENA PROMACHOS fr IHE FOUNDATIONS of the base of the Athena Promachos statue which once stood on the Acropolis of Athens lie about forty meters to the east of the Propy- laea and almost on.the axis of that great building (Figure 1).1 Fig. 1. The Athena Promachos As the Promachos statue was erected to commemorate the battle of Marathon, or possibly the Persian Wars in general, it is likely that the dedicatory inscription referred to this fact and that trophies won in the battles against the Persians were 1 When E. Beule wrote his great book L'Acropole d'Athe'nes, he reported (III, p. 307) as an already established fact the assignment of certain foundations and rock cuttings to the pedestal of the Promachos monument; compare also W. judeich, Topographie von Athen2, pp. 234-235; G. Lippold, R.E., s.v. Pheidias, cols. 1924-1925; C. Picard, Mai el d'Archeologie Grecql e, II, pp. 338-342. W. B. Dinsmoor assigned (A.J.A., XXV, 1921, p. 128, fig. 1) a fragment of an ovolo moulding to the capping course of the pedestal; compare also L. Shoe, Profiles of Greek Mouldings, p. 19 and plates C, 2, and IX, 6; G. P. Stevens, H:esperia, V, 1936, pp. 495, note 3, and 496, fig. 46. G. P. Stevens examined in detail the architectural remains (Hesperia, V, 1936, pp. 491-499, and figs. 42-49), and the present report is a continuation of his study based on the attribution by A. E. Raubitschek of two inscribed blocks to the lowest marble course of the pedestal (A.J.A., XLIV, 1940, p. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015)

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 31 | 2018 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015) Angelos Chaniotis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2741 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2741 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2018 Number of pages: 167-219 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, “Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015)”, Kernos [Online], 31 | 2018, Online since 01 October 2020, connection on 25 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/2741 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2741 This text was automatically generated on 25 January 2021. Kernos Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015) 1 Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015) Angelos Chaniotis To the memory of David Jordan 1 The 28th issue of the EBGR presents epigraphic corpora and new epigraphic finds published in 2015. I have only included a few contributions to the reading and interpretation of old finds as well as a small selection of publications that adduce inscriptions for the study of religious phenomena. I have also summarizes some publications of earlier years that had not been included in earlier issues of the EBGR (2007–2013). 2 In this issue, I summarize the content of new corpora from Athens (34), Macedonia (56. 109), Termessos (64), and Hadrianopolis (79) that mainly contain dedications, but also records of manumission through dedication to deities (56). The two most important new inscriptions are the incantations from Selinous (?), known as the ‘Getty hexameters’ and a cult regulation from Thessaly. -

Ancient Greece Around the Museum Gallery Trail

Ancient Greece around the Museum Gallery Trail USE this trail to fi nd Ancient Greek objects around the museum when the main Greek galleries are booked by another group. This trail does NOT include Greece (16), Aegean World (20), Money (7) or the Cast Gallery (14). GO OUTSIDE THE BUILDING TO THE FORECOURT The Ashmolean was built in 1845 in the style of an Ancient Greek temple. LOOK closely at the building and fi nd these elements of Greek archtictecture. DRAW a line between the labels and the pictures below. Pediment Classical column Key pattern Capital Mythical beast Apollo Apollo fact In the Ancient Greek world, Apollo was the god of music, poetry and the arts. He was the son of Zeus, king of all the gods. RE-ENTER THE MUSEUM AND FIND OUT MORE Ancient Greece around the Museum Gallery Trail GO TO: Ground fl oor, Gallery 21: Greek and Roman Sculpture MEET Athena a famous Greek goddess. Goddess Fact This is Athena the patron goddess of Athens. She is also the goddess of wisdom and warfare. She always wears a helmet and the ‘mask of Medusa’ on her breast plate. LOOK closely at Athena’s breast plate. It shows the face of the gorgon Medusa with snakes for hair. Greek myths tell us that if you looked Medusa in the eye you would be turned to stone! DRAW Medusa’s face onto this picture of the breastplate. In this gallery HUNT for: A giant head of the God Apollo A throne with Griffi n wings on the side Griffi n Information The Greek hero Herakles fi ghting A griffi n is a mythical creature with the with a lion. -

(Eponymous) Heroes

is is a version of an electronic document, part of the series, Dēmos: Clas- sical Athenian Democracy, a publicationpublication ofof e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org]. e electronic version of this article off ers contextual information intended to make the study of Athenian democracy more accessible to a wide audience. Please visit the site at http:// www.stoa.org/projects/demos/home. Athenian Political Art from the fi h and fourth centuries: Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes S e Cleisthenic reforms of /, which fi rmly established democracy at Ath- ens, imposed a new division of Attica into ten tribes, each of which consti- tuted a new political and military unit, but included citizens from each of the three geographical regions of Attica – the city, the coast, and the inland. En- rollment in a tribe (according to heredity) was a manda- tory prerequisite for citizenship. As usual in ancient Athenian aff airs, politics and reli- gion came hand in hand and, a er due consultation with Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, each new tribe was assigned to a particular hero a er whom the tribe was named; the ten Amy C. Smith, “Athenian Political Art from the Fi h and Fourth Centuries : Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes,” in C. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy (A.(A. MahoneyMahoney andand R.R. Scaife,Scaife, edd.,edd., e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org], . © , A.C. Smith. tribal heroes are thus known as the eponymous (or name giving) heroes. T : Aristotle indicates that each hero already received worship by the time of the Cleisthenic reforms, although little evi- dence as to the nature of the worship of each hero is now known (Aristot.