The Case of the Parthenon Sculptures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

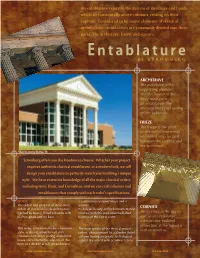

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

Full Thesis Text Only

A DIACHRONIC EXAMINATION OF THE ERECHTHEION AND ITS RECEPTION Alexandra L. Lesk, B.A., M.St. (Oxon.), M.A. Presented to McMicken College of Arts and Sciences and the Department of Classics of the University of Cincinnati in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2004 Committee: C. Brian Rose (Chair) Jack L. Davis Kathleen M. Lynch J. James Coulton Abstract iii ABSTRACT “A Diachronic Examination of the Erechtheion and Its Reception” examines the social life of the Ionic temple on the Athenian Akropolis, which was built in the late 5th century B.C. to house Athens’ most sacred cults and relics. Using a contextualized diachronic approach, this study examines both the changes to the Erechtheion between its construction and the middle of the 19th century A.D., as well as the impact the temple had on the architecture and art of these successive periods. This approach allows the evidence to shed light on new areas of interest such as the Post-Antique phases of the building, in addition to affording a better understanding of problems that have plagued the study of the Erechtheion during the past two centuries. This study begins with a re-examination of all the pertinent archaeological, epigraphical, and literary evidence, and proposes a wholly new reconstruction of how the Erechtheion worked physically and ritually in ancient times. After accounting for the immediate influence of the Erechtheion on subsequent buildings of the Ionic order, an argument for a Hellenistic rather than Augustan date for the major repairs to the temple is presented. -

Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon

ATHENIANS AND ELEUSINIANS IN THE WEST PEDIMENT OF THE PARTHENON (PLATE 95) T HE IDENTIFICATION of the figuresin the west pedimentof the Parthenonhas long been problematic.I The evidencereadily enables us to reconstructthe composition of the pedimentand to identify its central figures.The subsidiaryfigures, however, are rath- er more difficult to interpret. I propose that those on the left side of the pediment may be identifiedas membersof the Athenian royal family, associatedwith the goddessAthena, and those on the right as membersof the Eleusinian royal family, associatedwith the god Posei- don. This alignment reflects the strife of the two gods on a heroic level, by referringto the legendary war between Athens and Eleusis. The recognition of the disjunctionbetween Athenians and Eleusinians and of parallelism and contrastbetween individualsand groups of figures on the pedimentpermits the identificationof each figure. The referenceto Eleusis in the pediment,moreover, indicates the importanceof that city and its majorcult, the Eleu- sinian Mysteries, to the Athenians. The referencereflects the developmentand exploitation of Athenian control of the Mysteries during the Archaic and Classical periods. This new proposalfor the identificationof the subsidiaryfigures of the west pedimentthus has critical I This article has its origins in a paper I wrote in a graduateseminar directedby ProfessorJohn Pollini at The Johns Hopkins University in 1979. I returned to this paper to revise and expand its ideas during 1986/1987, when I held the Jacob Hirsch Fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In the summer of 1988, I was given a grant by the Committeeon Research of Tulane University to conduct furtherresearch for the article. -

Lord Elgin and the Ottomans: the Question of Permission

Yeshiva University, Cardozo School of Law LARC @ Cardozo Law Articles Faculty 2002 Lord Elgin and the Ottomans: The Question of Permission David Rudenstine Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/faculty-articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David Rudenstine, Lord Elgin and the Ottomans: The Question of Permission, 23 Cardozo Law Review 449 (2002). Available at: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/faculty-articles/167 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty at LARC @ Cardozo Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of LARC @ Cardozo Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. LORD ELGIN AND THE OTTOMANS: THE QUESTION OF PERMISSION David Rudenstine* In the early morning light on July 31, 1801, a ship-carpenter, five crew members, and twenty Athenian laborers "mounted the walls" of the Parthenon and with the aid of ropes and pulleys detached and lowered a sculptured marble block depicting a youth and centaur in combatJ The next day the group lowered a second sculptured marble from the magnificent templet Within months, the workers had lowered dozens of additional marble sculptures, and within a few years, most of the rest of the Parthenon's priceless marbles were removed.^ These fabulous marbles, sculptured during the age of Pericles'' under the guiding hand of Phidias' out of fine white Pentelic marble quarried ten miles from Athens and hauled by ox-cart to the Acropolis,® had remained on the Parthenon for 2,200 years before being removed. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

Psychologically Safe Workplaces: Utopia Revisited

GEORGIOS P. PIPEROPOULOS PSYCHOLOGICALLY SAFE WORKPLACES: UTOPIA REVISITED 2 Psychologically Safe Workplaces: Utopia Revisited 1st edition © 2018 Georgios P. Piperopoulos & bookboon.com ISBN 978-87-403-2421-1 Peer review by Professor Tyrone Pitsis, Durham University Business School Dedicated to a eutopia where employers and employees will no longer just co-exist but thrive together. 3 PSYCHOLOGICALLY SAFE WORKPLACES: UTOPIA REVISITED CONTENTS CONTENTS About the author 7 Prolegomena 9 PART ONE - Psychologically safe workplaces: Utopia revisited 15 1 Psychologically safe workplaces 17 2 The concept of ‘Utopia’ in literature 24 3 The concept of ‘Utopia’ in political economy 27 PART TWO – A journey through History 33 4 The Biblical ‘Garden of Eden’: ‘Paradise’ as a religious ‘Utopia’ 34 5 The Giza pyramids: History ‘made’ in Hollywood 38 6 Pericles and the Acropolis of Athens 41 Free eBook on Learning & Development By the Chief Learning Officer of McKinsey Download Now 4 PSYCHOLOGICALLY SAFE WORKPLACES: UTOPIA REVISITED CONTENTS PART THREE – From the British Industrial Revolution to the Great Depression and the ‘New Deal’ programs in America 45 7 The British Industrial Revolution 47 8 Unions and Unionism 51 8.1 Unionism in Britain 52 8.2 Unionism in the USA 53 8.3 Unionism in Germany 54 8.4 Unionism in France 57 9 Tsarist Russia and the Bolshevik Revolutions 60 9.1 Tsarist Russia 60 9.2 The Bolshevik Revolutions with Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin as the three protagonists 63 10 The Great Depression and the ‘New Deal’ Programs in America 68 PART -

Athena from a House on the Areopagus

ATHENA FROM A HOUSE ON THE AREOPAGUS (PLATES 107-112) E XCAVATIONS in 1970 and 1971 in the Athenian Agora revealed a remarkablecol- lection of sculpture from one of the largest of the late Roman houses on the slopes of the Areopagus.1This house, now called House C, was built in the 4th century after Christ with a spaciousplan includingtwo peristylecourts, and it was filled with Greek and Roman marble sculpturesof exceptional quality.2Two significantworks from the house have been I It is a pleasure to acknowledgethe cooperationof H. A. Thompson, T. L. Shear,Jr., and J. McK. Camp II of the Agora Excavationsand Museum, M. Brouskariof the AkropolisMuseum, N. Peppa-Delmouzouof the Epigraphical Museum, and K. Krystalli-Votsi of the National ArchaeologicalMuseum in Athens for allowing me to study and photograph the sculptures included here. I am especially grateful to Evelyn B. Harrison for her continuing encouragementand for permission to publish the Agora material, and to the AmericanSchool of Classical Studies at Athens for its friendly assistance. Works frequentlycited are abbreviatedas follows: Bieber, Copies = M. Bieber, Ancient Copies: Contributionsto the History of Greek and Roman Art, New York 1977 Boardman,GSCP = J. Boardman,Greek Sculpture: The ClassicalPeriod, New York 1985 Karouzou = S. Karouzou, National ArchaeologicalMuseum: Collection of Sculpture. A Cata- logue, Athens 1968 Lawton = C. L. Lawton, Attic Document Reliefs of the Classicaland Hellenistic Periods, diss. PrincetonUniversity, 1984 Leipen = N. Leipen, Athena Parthenos:A Reconstruction,Toronto 1971 Meyer = M. Meyer, Die griechischen Urkundenreliefs,AM Beiheft 13, Berlin 1989 Richter, SSG4 = G. M. A. Richter, The Sculptureand Sculptorsof the Greeks,4th ed., New Haven 1970 Ridgway, FCS = B. -

The Acropolis

November 2010 The Acropolis Acropolis is actually a generic Greek term referring to citadel on high ground originally designed for defense, and a number of Ancient Greek cities could boast such, such as Argos, Thebes, and Corinth. It was Athen’s acropolis, though that has become the Acropolis to the modern world. The Acropolis was formally proclaimed as the pre-eminent monument on the European Cultural Heritage list of monuments in 2007. The Acropolis is a flat-topped rock which rises 490 ft above sea level in the city of Athens, with a surface area of about 3 hectares. By the time of Pericles, during the Golden Age of Athens (460–430 BC), a number of temples had already been build and destroyed on the Acropolis, but most of the major temples were rebuilt under Pericles, Phidias (a great Athenian sculptor) and Ictinus and Callicrates (two famous architects) . During the 5th century BC, the Acropolis gained its final shape. After winning at Eurymedon in 468 BC, Cimon and Themistocles ordered the reconstruction of southern and northern walls, and Pericles entrusted the building of the Parthenon to Ictinus and Phidias. The Parthenon is the dominant building one sees standing atop the Acropolis today. It has been judged by architects as the most perfect building ever built by Man, and it undoubtedly is one of the major reasons why the Acropolis is so famous. The entrance to the Acropolis was a monumental gateway called the Propylaea. To the south is the tiny Temple of Athena Nike. A bronze statue of Athena, by Phidias, originally stood at its centre. -

Mapping the Limits of Repatriable Cultural Heritage: a Case Study of Stolen Flemish Art in French Museums

_________________ COMMENT _________________ MAPPING THE LIMITS OF REPATRIABLE CULTURAL HERITAGE: A CASE STUDY OF STOLEN FLEMISH ART IN FRENCH MUSEUMS † PAIGE S. GOODWIN INTRODUCTION......................................................................................674 I. THE NAPOLEONIC REVOLUTION AND THE CREATION OF FRANCE’S MUSEUMS ................................................676 A. Napoleon and the Confiscation of Art at Home and Abroad.....677 B. The Second Treaty of Paris ....................................................679 II. DEVELOPMENT OF THE LAW OF RESTITUTION ...............................682 A. Looting and War: From Prize Law to Nationalism and Cultural-Property Internationalism .................................682 B. Methods of Restitution Today: Comparative Examples............685 1. The Elgin Marbles and the Problem of Cultural-Property Internationalism........................687 2. The Italy-Met Accord as a Restitution Blueprint ...689 III. RESTITUTION OF FLEMISH ART AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS IN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE LAW .........................................................692 A. Why Should France Return Flemish Art Now?.........................692 1. Nationalism .............................................................692 2. Morality and Legality ..............................................693 3. Universalism............................................................694 † J.D. Candidate, 2009, University of Pennsylvania Law School; A.B., 2006, Duke Uni- versity. Many thanks to Professors Hans J. Van Miegroet -

The Stolen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in World War Ii?

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Faculty Articles and Essays Faculty Scholarship 1999 The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? Barbara Tyler Cleveland State University, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Publisher's Statement Copyright permission granted by the Rutgers University Law Journal. Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Original Citation Barbara Tyler, The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? 30 Rutgers Law Journal 441 (1999) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Articles and Essays by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 30 Rutgers L.J. 441 1998-1999 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon May 21 10:04:33 2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0277-318X THE STOLEN MUSEUM: HAVE UNITED STATES ART MUSEUMS BECOME INADVERTENT FENCES FOR STOLEN ART WORKS LOOTED BY THE NAZIS IN WORLD WAR II? BarbaraJ. -

A Mystery in Marble: Examining a Portrait Statue Through Science and Art

A Mystery in Marble: Examining a Portrait Statue through Science and Art lisa r. brody and carol e. snow Suffering from exposure to the elements, the purchased by a French private collector who unidentified woman was wrapped in a blan- placed the statue in a Parisian garden, where ket and shipped across the English Channel it endured two more decades of outdoor to an undisclosed location in Paris, her exact exposure to urban pollutants and acid rain. age and identity unknown. Later, traveling In December 2007, the piece was shipped with a French passport, she arrived in the to Sotheby’s in New York to be sold at an United States and made her way through the auction of Greek and Roman antiquities.2 streets of Manhattan to an elegant building Looking beyond the superficial, curators on the Upper East Side. Standing in a hall- and conservators from the Yale University way there on a cold December afternoon, the Art Gallery discerned the figure’s full poten- woman’s discolored appearance and awkward tial as a fine example of Roman sculpture pose attracted little attention (fig. 1). and arranged for its final journey to New The story of the Roman marble statue Haven, Connecticut. There, the story of a woman that is the subject of this article would continue to unfold through scholarly has the plot twists and intricacies of a pop- research, scientific analysis, and a lengthy ular novel. Although the very beginning conservation treatment. remains unwritten, the ending is a happy one The six-foot-tall marble statue of a for Yale.