Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program Hilary Kao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tesla Motors

AUGUST 2014 TESLA MOTORS: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, OPEN INNOVATION, AND THE CARBON CRISIS DR MATTHEW RIMMER AUSTRALIAN RESEARCH COUNCIL FUTURE FELLOW ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LAW The Australian National University College of Law, Canberra, ACT, 0200 Work Telephone Number: (02) 61254164 E-Mail Address: [email protected] 1 Introduction Tesla Motors is an innovative United States manufacturer of electric vehicles. In its annual report for 2012, the company summarizes its business operations: We design, develop, manufacture and sell high-performance fully electric vehicles and advanced electric vehicle powertrain components. We own our sales and service network and have operationally structured our business in a manner that we believe will enable us to rapidly develop and launch advanced electric vehicles and technologies. We believe our vehicles, electric vehicle engineering expertise, and operational structure differentiates us from incumbent automobile manufacturers. We are the first company to commercially produce a federally-compliant electric vehicle, the Tesla Roadster, which achieves a market-leading range on a single charge combined with attractive design, driving performance and zero tailpipe emissions. As of December 31, 2012, we had delivered approximately 2,450 Tesla Roadsters to customers in over 30 countries. While we have concluded the production run of the Tesla Roadster, its proprietary electric vehicle powertrain system is the foundation of our business. We modified this system -

Cadmium Telluride Photovoltaics - Wikipedia 1 of 13

Cadmium telluride photovoltaics - Wikipedia 1 of 13 Cadmium telluride photovoltaics Cadmium telluride (CdTe) photovoltaics describes a photovoltaic (PV) technology that is based on the use of cadmium telluride, a thin semiconductor layer designed to absorb and convert sunlight into electricity.[1] Cadmium telluride PV is the only thin film technology with lower costs than conventional solar cells made of crystalline silicon in multi-kilowatt systems.[1][2][3] On a lifecycle basis, CdTe PV has the smallest carbon footprint, lowest water use and shortest energy payback time of any current photo voltaic technology. PV array made of cadmium telluride (CdTe) solar [4][5][6] CdTe's energy payback time of less than a year panels allows for faster carbon reductions without short- term energy deficits. The toxicity of cadmium is an environmental concern mitigated by the recycling of CdTe modules at the end of their life time,[7] though there are still uncertainties[8][9] and the public opinion is skeptical towards this technology.[10][11] The usage of rare materials may also become a limiting factor to the industrial scalability of CdTe technology in the mid-term future. The abundance of tellurium—of which telluride is the anionic form— is comparable to that of platinum in the earth's crust and contributes significantly to the module's cost.[12] CdTe photovoltaics are used in some of the world's largest photovoltaic power stations, such as the Topaz Solar Farm. With a share of 5.1% of worldwide PV production, CdTe technology accounted for more than half of the thin film market in 2013.[13] A prominent manufacturer of CdTe thin film technology is the company First Solar, based in Tempe, Arizona. -

AS You Sow on Creating Greener Solar PV Panels

AS You Sow on Creating Greener Solar PV Panels Andrew Burger. March 28, 2012 Advocating solar PV manufacturers adopt a set of industry best practices, a new survey and report highlights the environmental benefits of using solar photovoltaic (PV) energy as compared to fossil fuels, while at the same time criticizing ongoing, outsized government support for fossil fuel production. “Even though there are toxic compounds used in the manufacturing of many solar panels, the generation of electricity from solar energy is much safer to both the environment and workers than production of electricity from coal, natural gas, or nuclear,” stated Amy Galland, PhD and research director at non-profit group As You Sow. “For example, once a solar panel is installed, it generates electricity with no emissions of any kind for decades, whereas coal-fired power plants in the U.S. emitted nearly two billion tons of carbon dioxide and millions of tons of toxic compounds in 2010 alone.” Based on an international survey of more than 100 solar PV manufac- turers, the best practices in As You Sow’s report, “Clean & Green: Best Practices in Photovoltaics” aim to protect the employee and community health and safety, as well as the broader environment. Also analyzed are investor considerations regarding environmental, social and govern- ance for responsible management of solar PV manufacturing business- es. The best practices listed were determined in consultation with sci- entists, engineers, academics, government labs and industry consult- ants. Solar PV CSR survey and report card “We have been working with solar companies to study and minimize the environmental health and safety risks in the production of solar panels and the industry has embraced the opportunities,” Vasilis Fthenakis, PhD and director of the National PV Environmen- tal Health and Safety Research Center at Brookhaven National Laboratory and director of the Center for Life Cycle Analysis at Columbia University, explained. -

Federal Incentives for Clean Energy After Solyndra: a Post-Recovery Act Precipice

North Dakota Law Review Volume 87 Number 4 Article 7 1-1-2011 Federal Incentives for Clean Energy After Solyndra: A Post- Recovery Act Precipice John A. Herrick Cara S. Elias Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Herrick, John A. and Elias, Cara S. (2011) "Federal Incentives for Clean Energy After Solyndra: A Post- Recovery Act Precipice," North Dakota Law Review: Vol. 87 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr/vol87/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Dakota Law Review by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HERRICK 10-15-10 MFE (DO NOT DELETE) 10/15/2012 10:13 AM FEDERAL INCENTIVES FOR CLEAN ENERGY AFTER SOLYNDRA: A POST–RECOVERY ACT PRECIPICE JOHN A. HERRICK* & CARA S. ELIAS** I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 628 II. FEDERAL NON-TAX INCENTIVE PROGRAMS .................. 630 A. TYPES OF FEDERAL INCENTIVES FOR CLEAN ENERGY ........ 630 1. PURPA Renewable Power Purchase Requirements ...... 630 2. Federal Financial Assistance Programs for Clean Energy ............................................................................ 632 3. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Cooperative Agreements ..................................................................... 635 4. DOE Technology Investment Agreements ...................... 637 5. Federal Loan Guarantees .............................................. 638 6. Rights to Intellectual Property Under Federal Incentive Programs ........................................................................ 640 * John A. Herrick is Senior Counsel in the Denver office of Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck LLP where he specializes in the clean technology practice area. -

The Water-Energy Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities Overview

U.S. Department of Energy The Water-Energy Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities JUNE 2014 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary.............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 DOE’s Motivation and Role .................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 The DOE Approach ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Opportunities ............................................................................................................................................. 4 References .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Laying the Foundation for a Bright Future: Assessing Progress

Laying the Foundation for a Bright Future Assessing Progress Under Phase 1 of India’s National Solar Mission Interim Report: April 2012 Prepared by Council on Energy, Environment and Water Natural Resources Defense Council Supported in part by: ABOUT THIS REPORT About Council on Energy, Environment and Water The Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) is an independent nonprofit policy research institution that works to promote dialogue and common understanding on energy, environment, and water issues in India and elsewhere through high-quality research, partnerships with public and private institutions and engagement with and outreach to the wider public. (http://ceew.in). About Natural Resources Defense Council The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) is an international nonprofit environmental organization with more than 1.3 million members and online activists. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have worked to protect the world’s natural resources, public health, and the environment. NRDC has offices in New York City; Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles; San Francisco; Chicago; Livingston and Beijing. (www.nrdc.org). Authors and Investigators CEEW team: Arunabha Ghosh, Rajeev Palakshappa, Sanyukta Raje, Ankita Lamboria NRDC team: Anjali Jaiswal, Vignesh Gowrishankar, Meredith Connolly, Bhaskar Deol, Sameer Kwatra, Amrita Batra, Neha Mathew Neither CEEW nor NRDC has commercial interests in India’s National Solar Mission, nor has either organization received any funding from any commercial or governmental institution for this project. Acknowledgments The authors of this report thank government officials from India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), NTPC Vidyut Vyapar Nigam (NVVN), and other Government of India agencies, as well as United States government officials. -

The Solyndra Failurex

The Solyndra Failurex Majority Staff Report Prepared for the Use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce Fred Upton, Chairman U.S. House of Representatives 112th Congress August 2, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... ii TABLE OF NAMES .......................................................................................................... v I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 II. HISTORY OF THE COMMITTEE’S INVESTIGATION .................................... 5 III. DOE’S REVIEW OF THE SOLYNDRA LOAN APPLICATION AND CONDITIONAL COMMITMENT ........................................................................ 9 A. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 and The Establishment of the Loan Guarantee Program at DOE .............................................................................................................................. 9 B. Solyndra’s Application ................................................................................................... 10 C. Solyndra Loan Application Begins Due Diligence and Is Remanded by the First DOE Credit Committee (2008 and 2009) ................................................................................ 12 D. The Stimulus and Other Changes to the DOE Loan Guarantee Program Under the Obama Administration ................................................................................................... 16 E. Review -

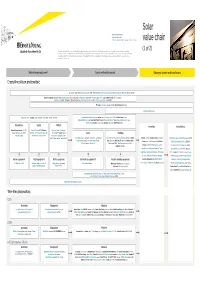

Lsoar Value Chain Value Chain

Solar Private companies in black Public companies in blue Followed by the founding date of companies less than 15 years old value chain (1 of 2) This value chain publication contains information gathered and summarized mainly from Lux Research and a variety of other public sources that we believe to be accurate at the time of ppggyublication. The information is for general guidance only and not intended to be a substitute for detailed research or the exercise of professional judgment. Neither EYGM Limited nor any other member of the global Ernst & Young organization nor Lux Research can accept responsibility for loss to any person relying on this publication. Materials and equipment Components and products Balance of system and installations Crystalline silicon photovoltaic GCL Silicon, China (2006); LDK Solar, China (2005); MEMC, US; Renewable Energy Corporation ASA, Norway; SolarWorld AG, Germany (1998) Bosch Solar Energy, Germany (2000); Canadian Solar, Canada/China (2001); Jinko Solar, China (2006); Kyocera, Japan; Sanyo, Japan; SCHOTT Solar, Germany (2002); Solarfun, China (2004); Tianwei New Energy Holdings Co., China; Trina Solar, China (1997); Yingli Green Energy, China (1998); BP Solar, US; Conergy, Germany (1998); Eging Photovoltaic, China SOLON, Germany (1997) Daqo Group, China; M. Setek, Japan; ReneSola, China (2003); Wacker, Germany Hyundai Heavy Industries,,; Korea; Isofoton,,p Spain ; JA Solar, China (();2005); LG Solar Power,,; Korea; Mitsubishi Electric, Japan; Moser Baer Photo Voltaic, India (2005); Motech, Taiwan; Samsung -

Tesla, Inc. Form 10-K Annual Report Filed 2017-03-01

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-K Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d) Filing Date: 2017-03-01 | Period of Report: 2016-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0001564590-17-003118 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Tesla, Inc. Mailing Address Business Address 3500 DEER CREEK RD 3500 DEER CREEK RD CIK:1318605| IRS No.: 912197729 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 PALO ALTO CA 94070 PALO ALTO CA 94070 Type: 10-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-34756 | Film No.: 17655025 650-681-5000 SIC: 3711 Motor vehicles & passenger car bodies Copyright © 2017 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2016 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-34756 Tesla, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 91-2197729 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 3500 Deer Creek Road Palo Alto, California 94304 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (650) 681-5000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, $0.001 par value The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Bankrupt Companies

The List of Fallen Solar Companies: 2015 to 2009: S.No Year/Status Company Name and Details 118 2015 Enecsys (microinverters) bankrupt -- Enecsys raised more than $55 million in VC from investors including Wellington Partners, NES Partners, Good Energies and Climate Change Capital Private Equity for its microinverter technology. 117 2015 QBotix (trackers) closed -- QBotix had a two-axis solar tracker system where the motors, instead of being installed two per tracker, were moved around by a rail-mounted robot that adjusted each tracker every 40 minutes. But while QBotix was trying to gain traction, single-axis solar trackers were also evolving and driving down cost. QBotix raised more than $19.5 million from Firelake, NEA, DFJ JAIC, Siemens Ventures, E.ON and Iberdrola. 116 2015 Solar-Fabrik (c-Si) bankrupt -- German module builder 115 2015 Soitec (CPV) closed -- France's Soitec, one of the last companies with a hope of commercializing concentrating photovoltaic technology, abandoned its solar business. Soitec had approximately 75 megawatts' worth of CPV projects in the ground. 114 2015 TSMC (CIGS) closed -- TSMC Solar ceased manufacturing operations, as "TSMC believes that its solar business is no longer economically sustainable." Last year, TSMC Solar posted a champion module efficiency of 15.7 percent with its Stion- licensed technology. 113 2015 Abengoa -- Seeking bankruptcy protection 112 2014 Bankrupt, Areva's solar business (CSP) closed -- Suffering through a closed Fukushima-inspired slowdown in reactor sales, Ausra 111 2014 Bankrupt, -

Solar Projects: DOE Section 1705 Loan Guarantees Name Redacted Analyst in Energy Policy

Solar Projects: DOE Section 1705 Loan Guarantees name redacted Analyst in Energy Policy October 25, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R42059 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Solar Projects: DOE Section 1705 Loan Guarantees ince Solyndra, a solar system manufacturing company that received a $535 million loan guarantee from the Department of Energy (DOE), filed for bankruptcy in September of S2011 there has been much congressional interest in better understanding the characteristics of renewable energy projects, specifically solar projects, that have received DOE loan guarantees. The objective of this report is to provide Congress with insight regarding solar projects supported by DOE’s loan guarantee program, the risk characteristics of these projects, and how other DOE loan guarantee projects are either similar to or different from the Solyndra solar manufacturing project. Key Points • DOE’s Loan Programs Office (LPO) administers three separate loan programs: (1) Section 17031 loan guarantees, (2) Section 17052 loan guarantees, and (3) Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing (ATVM) loans. • To date, all loan guarantees for solar projects have been provided under LPO’s Section 1705 program. • LPO’s Section 1705 program has closed transactions that guarantee approximately $16.15 billion of loans for renewable energy projects. Roughly 82% ($13.27 billion) of Section 1705 loan guarantees have been for solar projects. • Solar projects supported by Section 1705 loan guarantees generally fall into one of two categories: (1) solar manufacturing, or (2) solar generation. Each category has different financial, operational, and technology risk characteristics. • Four solar manufacturing projects, including Solyndra, have received loan guarantees totaling $1.28 billion, which is approximately 8% of the total dollar value of loans guaranteed under the Section 1705 program. -

Mintz Levin Project Finance Greenpaper

whitepaper Renewable Energy Project Finance in the U.S.: An Overview and Midterm Outlook Renewable Energy Project Finance in the U.S.: An Overview and Midterm Outlook I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Wind, solar and geothermal energy projects in the United States are typically paid for using an approach known as “project finance.” This is a structure employed to finance capital-intensive projects that are either difficult to support on a corporate balance sheet or that become more attractive when financed on their own. Project financing structures will vary on a project-by-project basis, but renewable energy projects in the U.S. utilizing project financing generally rely upon a mix of direct equity investors, tax equity investors and project-level loans provided by a syndicate of banks. Turbulence in the financial markets began disrupting the flow of project financing (both equity and debt) into renewable energy projects in the U.S. in the fourth quarter of 2008. Nearly two years later, the availability of project financing has improved considerably due to the thawing of the lending markets, with a return to longer tenors on term-debt, and legislative support mechanisms introduced as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)—particularly the ITC cash grant. In this report, we provide an update on the current terms and availability of project financing for large-scale wind, solar and geothermal projects in the U.S. and forecast the amount of project financing we expect to be sought by the sector through 2012. In analyzing where this financing is likely to come from, we address the potential impacts of the upcoming expiration of the cash grant and changes to the tax equity supply—two main themes in the renewable energy project financing arena at present.