Venture Capital and Cleantech: the Wrong Model for Clean Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanosolar Is Leading the “Third Wave” of Solar Power Technology: the First

Nanosolar is leading the “Third Wave” of solar power technology: ▪ The First Wave started with the introduction of silicon-wafer based solar cells over three decades ago. While ground-breaking, it is visible until today that this technology came out of a market environment with little concern for cost, capital efficiency, and the product cost / performance ratio. Despite continued incremental improvements, silicon-wafer cells have a built-in disadvantage of fundamentally high materials cost and poor capital efficiency. Because silicon does not absorb light very strongly, silicon wafer cells have to be very thick. And because wafers are fragile, their intricate handling complicates processing all the way up to the panel product. ▪ The Second Wave came about a decade ago with the arrival of the first commercial "thin-film" solar cells. This established that new solar cells based on a stack of layers 100 times thinner than silicon wafers can make a solar cell that is just as good. However, the first thin-film approaches were handicapped by two issues: 1. The cell's semiconductor was deposited using slow and expensive high-vacuum based processes because it was not known how to employ much simpler and higher-yield printing processes (and how to develop the required semiconductor ink). 2. The thin films were deposited directly onto glass as a substrate, eliminating the opportunity of ▪ using a conductive substrate directly as electrode (and thus avoiding bottom-electrode deposition cost), ▪ achieving a low-cost top electrode of high performance, ▪ employing the yield and performance advantages of individual cell matching & sorting, ▪ employing high-yield continuous roll-to-roll processing, and ▪ developing high-power high-current panels with lower balance-of-system cost. -

Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program Hilary Kao

William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review Volume 37 | Issue 2 Article 4 Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program Hilary Kao Repository Citation Hilary Kao, Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program, 37 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol'y Rev. 425 (2013), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol37/iss2/4 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr BEYOND SOLYNDRA: EXAMINING THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY’S LOAN GUARANTEE PROGRAM HILARY KAO* ABSTRACT In the year following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011, the renewable and clean energy industries faced significant turmoil— from natural disasters, to political maelstroms, from the Great Recession, to U.S. debt ceiling debates. The Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program (“DOE LGP”), often a target since before it ever received a dollar of appropriations, has been both blamed and defended in the wake of the bankruptcy filing of Solyndra, a California-based solar panel manufac- turer, in September 2011, because of the $535 million loan guarantee made to it by the Department of Energy (“DOE”) in 2009.1 Critics have suggested political favoritism in loan guarantee awards and have questioned the government’s proper role in supporting renewable energy companies and the renewable energy industry generally.2 This Article looks beyond the Solyndra controversy to examine the origin, structure and purpose of the DOE LGP. It asserts that loan guaran- tees can serve as viable policy tools, but require careful crafting to have the potential to be effective programs. -

How Founders Use External Advice to Improve Their Firm's Chance of Succeeding

The dynamics of forming a technology based start-up: How founders use external advice to improve their firm's chance of succeeding by Nick Cravalho B.S. Mechanical Engineering University of California, Berkeley, 2000 Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology May 2007 2007 Nick Cravalho. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium not known or hereafter created. Signature of Author Nick Cravalho System Design and Management Program May 2007 Certified by Diane Burton Thesis Supervisor Sloan School of Management Certified by _ Patrick Hale Director OASSACHUSETTS INS System Design and Management Program OF TECHNOLOGY FEB 0 1 2008 BARKER LIBRARIES The dynamics of forming a technology based start-up: How founders use external advice to improve their firm's chance of succeeding by Nick Cravalho Submitted to the System Design and Management Program on May 11, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management Abstract External advice can be a valuable resource for founders of high technology startup companies. As with any resource, the pursuit and efficient use of the external advice resource is one of the greatest challenges for founders. This thesis examines how the founders of eleven US venture-backed high-tech companies leveraged external advice to their advantage. -

Solar Energy: a New Day Dawning?: Silicon Valley Sunrise Oliver Morton Oliver Morton Is Nature's Chief News and Features Editor

Solar energy: A new day dawning?: Silicon Valley sunrise Oliver Morton Oliver Morton is Nature's chief news and features editor. Abstract Sunlight is a ubiquitous form of energy, but not as yet an economic one. In the first of two features, Oliver Morton looks at how interest in photovoltaic research is heating up in California's Silicon Valley. In the second, Carina Dennis talks to Australian researchers hoping to harness the dawn Sun's heat. The Sun provides Earth with as much energy every hour as human civilization uses every year. If you are a solarenergy enthusiast, that says it all. No other energy supply could conceivably be as plentiful as the 120,000 terawatts the Sun provides ceaselessly and unbidden. If the tiniest fraction of that sunlight were to be captured by photovoltaic cells that turn it straight into electricity, there would be no need to emit any greenhouse gases from any power plant. Thanks to green thoughts like that, and to generous subsidies from governments in Japan and Germany, the solarcell market has been growing on average by a heady 31% a year for the past decade (see chart, below). One of the most bullish industry analysts, Michael Rogol, sees the industry increasing from about US$12 billion in 2005 to as much as $70 billion in 2010. Although not everyone predicts such impressive growth, a 20–25% annual rise is widely expected. The market for shares in solarenergy companies is correspondingly buoyant. And yet in the projections of energy supply made by policy analysts and climate wonks, solar remains so marginal as to be barely on the map at all. -

Federal Incentives for Clean Energy After Solyndra: a Post-Recovery Act Precipice

North Dakota Law Review Volume 87 Number 4 Article 7 1-1-2011 Federal Incentives for Clean Energy After Solyndra: A Post- Recovery Act Precipice John A. Herrick Cara S. Elias Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Herrick, John A. and Elias, Cara S. (2011) "Federal Incentives for Clean Energy After Solyndra: A Post- Recovery Act Precipice," North Dakota Law Review: Vol. 87 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr/vol87/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Dakota Law Review by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HERRICK 10-15-10 MFE (DO NOT DELETE) 10/15/2012 10:13 AM FEDERAL INCENTIVES FOR CLEAN ENERGY AFTER SOLYNDRA: A POST–RECOVERY ACT PRECIPICE JOHN A. HERRICK* & CARA S. ELIAS** I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 628 II. FEDERAL NON-TAX INCENTIVE PROGRAMS .................. 630 A. TYPES OF FEDERAL INCENTIVES FOR CLEAN ENERGY ........ 630 1. PURPA Renewable Power Purchase Requirements ...... 630 2. Federal Financial Assistance Programs for Clean Energy ............................................................................ 632 3. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Cooperative Agreements ..................................................................... 635 4. DOE Technology Investment Agreements ...................... 637 5. Federal Loan Guarantees .............................................. 638 6. Rights to Intellectual Property Under Federal Incentive Programs ........................................................................ 640 * John A. Herrick is Senior Counsel in the Denver office of Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck LLP where he specializes in the clean technology practice area. -

The Water-Energy Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities Overview

U.S. Department of Energy The Water-Energy Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities JUNE 2014 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK Table of Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................... i Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary.............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 DOE’s Motivation and Role .................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 The DOE Approach ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Opportunities ............................................................................................................................................. 4 References .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Solar PV Technology Development Report 2020

EUR 30504 EN This publication is a Technical report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s science and knowledge service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policymaking process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of this publication. For information on the methodology and quality underlying the data used in this publication for which the source is neither Eurostat nor other Commission services, users should contact the referenced source. The designations employed and the presentation of material on the maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Union concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Contact information Name: Nigel TAYLOR Address: European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy Email: [email protected] Name: Maria GETSIOU Address: European Commission DG Research and Innovation, Brussels, Belgium Email: [email protected] EU Science Hub https://ec.europa.eu/jrc JRC123157 EUR 30504 EN ISSN 2600-0466 PDF ISBN 978-92-76-27274-8 doi:10.2760/827685 ISSN 1831-9424 (online collection) ISSN 2600-0458 Print ISBN 978-92-76-27275-5 doi:10.2760/215293 ISSN 1018-5593 (print collection) Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 © European Union, 2020 The reuse policy of the European Commission is implemented by the Commission Decision 2011/833/EU of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. -

The Solyndra Failurex

The Solyndra Failurex Majority Staff Report Prepared for the Use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce Fred Upton, Chairman U.S. House of Representatives 112th Congress August 2, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... ii TABLE OF NAMES .......................................................................................................... v I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 II. HISTORY OF THE COMMITTEE’S INVESTIGATION .................................... 5 III. DOE’S REVIEW OF THE SOLYNDRA LOAN APPLICATION AND CONDITIONAL COMMITMENT ........................................................................ 9 A. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 and The Establishment of the Loan Guarantee Program at DOE .............................................................................................................................. 9 B. Solyndra’s Application ................................................................................................... 10 C. Solyndra Loan Application Begins Due Diligence and Is Remanded by the First DOE Credit Committee (2008 and 2009) ................................................................................ 12 D. The Stimulus and Other Changes to the DOE Loan Guarantee Program Under the Obama Administration ................................................................................................... 16 E. Review -

Nanosolar & U.S. Department of Energy Solar America Initiative

Securing our Energy Independence and Sustaining our Environment March 2011 1 Our High-Speed Solar Cell and Panel Factories Can Be Built Cost Effectively Anywhere in the World We Do Not Need to Manufacture in Asia to Be Competitive: We can build in San Jose! San Jose, California, Global Headquarters & Solar Cell Production Factory, 200,000 sq ft Luckenwalde, Germany, Panel Assembly Factory, 500,000 sq ft 2 We Print Nanotechnology-enabled Ink on Rolls of Very Inexpensive Aluminum Foil Rapid processing using low cost equipment and the lowest cost metal substrate 3 Our Flexible Foil Cells Are Built in San Jose, CA . Rolls of printed foil processed and thin film layers added to complete electrical structure . Foil cut into individual, rectangular cells . Flexibility to tune cells’ power output for Utility, Commercial and Residential solar markets 4 We then Assemble these Cells into Utility-scale Panels . 84 cells welded together to form one solar panel . Cells sandwiched between two tempered glass plates . Glass plate edges sealed to protect against weather Specifically designed from the start to make Nanosolar utility-scale solar power plants competitive with fossil fuels 5 Nanosolar Power Plants Are Built in Municipal Areas Connection to Distribution Voltage Lowers Delivery Costs Nanosolar power plants can be constructed on landfills, brown fields and green fields, as well as on flat rooftops 6 Nanosolar CA Factory Expansion Can Create Thousands of Skilled Solar Jobs Each Year For every 100 MW of production: . Navigant: 1,000 downstream jobs in system integration, installation, and O&M . Deutsche Bank : 3,700 downstream jobs in system integration, installation, and O&M . -

Solar Projects: DOE Section 1705 Loan Guarantees Name Redacted Analyst in Energy Policy

Solar Projects: DOE Section 1705 Loan Guarantees name redacted Analyst in Energy Policy October 25, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R42059 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Solar Projects: DOE Section 1705 Loan Guarantees ince Solyndra, a solar system manufacturing company that received a $535 million loan guarantee from the Department of Energy (DOE), filed for bankruptcy in September of S2011 there has been much congressional interest in better understanding the characteristics of renewable energy projects, specifically solar projects, that have received DOE loan guarantees. The objective of this report is to provide Congress with insight regarding solar projects supported by DOE’s loan guarantee program, the risk characteristics of these projects, and how other DOE loan guarantee projects are either similar to or different from the Solyndra solar manufacturing project. Key Points • DOE’s Loan Programs Office (LPO) administers three separate loan programs: (1) Section 17031 loan guarantees, (2) Section 17052 loan guarantees, and (3) Advanced Technology Vehicle Manufacturing (ATVM) loans. • To date, all loan guarantees for solar projects have been provided under LPO’s Section 1705 program. • LPO’s Section 1705 program has closed transactions that guarantee approximately $16.15 billion of loans for renewable energy projects. Roughly 82% ($13.27 billion) of Section 1705 loan guarantees have been for solar projects. • Solar projects supported by Section 1705 loan guarantees generally fall into one of two categories: (1) solar manufacturing, or (2) solar generation. Each category has different financial, operational, and technology risk characteristics. • Four solar manufacturing projects, including Solyndra, have received loan guarantees totaling $1.28 billion, which is approximately 8% of the total dollar value of loans guaranteed under the Section 1705 program. -

Sunny Side up Varun Sivaram

Sunny Side Up Characterizing the US Military’s Approach to Solar Energy Policy Varun Sivaram CISAC Honors Thesis Advised by Professor Michael May and Professor Martha Crenshaw May 15, 2011 Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................... 2 The Puzzle ............................................................................................................................. 2 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Solar Power ....................................................................................................................... 4 Federal Policy ................................................................................................................... 6 DoD Renewables Initiatives .............................................................................................. 8 Looking Forward ................................................................................................................. 10 Chapter 2: Theoretical Frameworks for Real Policymaking ........................................... 12 Punctuated Equilibrium ....................................................................................................... 14 Bounded Rationality and Incrementalism .......................................................................... -

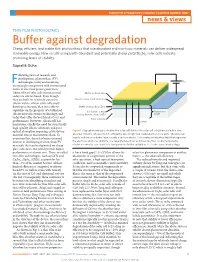

Buffer Against Degradation Cheap, Efficient, and Stable Thin Photovoltaics That Use Abundant and Non-Toxic Materials Can Deliver Widespread

PUBLISHED: 27 MARCH 2017 | VOLUME: 2 | ARTICLE NUMBER: 17057 news & views THIN-FILM PHOTOVOLTAICS Buffer against degradation Cheap, efficient, and stable thin photovoltaics that use abundant and non-toxic materials can deliver widespread renewable energy. New results using Earth-abundant and potentially cheap ZnO/Sb2Se3 solar cells indicate promising levels of stability. Supratik Guha ollowing years of research and development, photovoltaic (PV) Ftechnologies today are becoming VOC increasingly competitive with conventional forms of electrical power generation. About 93% of solar cells manufactured Metal electrode layer today are silicon-based. Even though they are built on relatively expensive Absorber layer (such as Sb2Se3) silicon wafers, silicon solar cells enjoy dominance because they were able to Buer layer (such as ZnO) capitalize on the progress of established Conductive coating Transparent to sunlight silicon microelectronics technology, and (such as fluorine-doped SnO2) today they offer the best blend of cost and Glass substrate performance. However, silicon still has Sunlight limitations, chiefly the need for structurally high-quality silicon substrates and poor optical absorption requiring active device Figure 1 | Typical architecture of a thin-film solar cell. A thin-film solar cell is built around a thin-film material tens of micrometres thick. To absorber material, whose role is to efficiently absorb light and create electron–hole pairs. The absorber overcome this, there has been sustained layer is matched to a buffer layer, usually a semiconductor. This creates an electrical field that separates interest in developing micron-thick PV the electrons and holes spatially. The separated electrons and holes are then conducted away by electrical contacts, one of which is transparent to let the sunlight in.