Laying the Foundation for a Bright Future: Assessing Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automatic Sun Tracking System with Dual Axis

AUTOMATIC SUN TRACKING SYSTEM WITH DUAL AXIS K Srinivasa Rao1, G.Sreedhara Babu2 and M.Rajesh3 1,2,3Department of Mechanical Engineering,V.R.Siddhartha Engineering College Abstract— The aim of this paper is to solve the problem of energy crisis which is considerably serious issue in today’s period. It is becoming essential to increase use of renewable sources of energy namely solar energy as compared to conventional sources for energy generation. Solar energy is rapidly gaining notoriety as an important means of expanding renewable energy resources. As such, it is vital that those in engineering fields understand the technologies associated with this area. Our project will include the design and construction of a microcontroller-based solar panel tracking system. It uses 8051 microcontroller and stepper motor to move solar panel according to position of sun. Photo resistors are also used to detect light intensity. Solar tracking allows more energy to be produced because the solar array is able to remain aligned to the sun. A technology namely solar tracking system is introduced to improve efficiency of solar cells by tracking sun’s energy. A working system will ultimately be demonstrated to validate the design. Problems and possible improvements will also be presented. A solar panel receives the most sunlight when it is perpendicular to the sun’s rays, but the sunlight direction changes regularly with changing seasons and weather. Currently, most solar panels are fixed, i.e., the solar array has a fixed orientation to the sky and does not turn to follow the sun. To increase the unit area illumination of sunlight on solar panels, we designed a solar tracking electricity generation system. -

Techniques to Upgrade Indian Solar Power Sector by Analysing the Top Ranking Solar Power Countries

IJRET: International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology eISSN: 2319-1163 | pISSN: 2321-7308 TECHNIQUES TO UPGRADE INDIAN SOLAR POWER SECTOR BY ANALYSING THE TOP RANKING SOLAR POWER COUNTRIES Shantanu Rawat1, Himanshi Rana2, Deepanvita Maurya3, Deepak Kumar4 1Department of Electrical, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies, Dehradun, India 2Department of Aerospace, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies, Dehradun, India 3Department of Mechanical, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies, Dehradun, India 4Assistant Professor, Department of Electrical, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies, Dehradun, India Abstract As fossil fuels are depleting day by day it is the high time to switch to renewable energy. Many countries have already realized this fact and have started focusing on the renewable energies. The main focus of all countries is on solar power [1]. Though many countries have developed themselves in solar power generation since last one decades but India hasn’t started yet. The major solar power producing countries are China, Germany and Japan and if we try to compare India with these countries we stand far apart in the queue. Though India has one of the best climatic conditions to support solar power generation. India is a sun-blessed country which has clear 300 days of sunshine, which is comparatively much more than the other countries [2]. The total power generated by India is 267,637.35 MW (till March 2015) and out of which we are generating only 5,050 MW through solar energy [3]. To satisfy the demand of power supply all over the country in future, we need to install more number of solar power plants such as to provide us maximum output as a result in much more advanced technique [4]. -

Government Initiatives for Solar Home Systems for Rural Electrification in India

International Journal of Home Science 2020; 6(3): 32-38 ISSN: 2395-7476 IJHS 2020; 6(3): 32-38 © 2020 IJHS Government initiatives for solar home systems for rural www.homesciencejournal.com Received: 21-06-2020 electrification in India: Outlook and Challenges Accepted: 10-09-2020 Neha Makol Neha Makol, Dr. Puja Gupta, Dr. Meenakshi Mital and Matt Syal Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Home Science, University of Delhi, Delhi, India Abstract Rural electrification has been the cornerstone of the government’s policies. India, being one of the fastest Dr. Puja Gupta growing economy, realised that the rapid increase in electricity demands will need cleaner energy Associate Professor, Department solution. India has been ranked 3rd for solar energy development in the Renewable Energy Country of Resource Management & Attractiveness Index due to its geographical location, average temperature and policy environment (EY, Design Application, Lady Irwin 2019). Innovative off-grid solar technologies like solar home systems have found a huge market in the College, University of Delhi, country since 2000s. Backed by strong policy support, solar home systems have been widely adopted by Delhi, India rural people for their basic lighting and electricity needs. This paper attempts to look at the initiatives Dr. Meenakshi Mital taken by the government to increase the adoption of solar home systems for rural electrification and its Associate Professor, Department challenges. of Resource Management & Design Application, Lady Irwin Keywords: renewable energy technologies (RET), decentralised energy solutions, off-grid solar College, University of Delhi, technologies, solar home systems (SHS) Delhi, India Introduction Matt Syal Access to electricity is at the centre of rural development. -

Download Report

Working paper/PM 2013:02 Innovation in Indian energy policy-Case studies on solar energi and energy efficiency technology deployment Denna rapport analyserar två konkreta exempel på hur Indien arbetar med energiteknik: National Solar Mission som syftar till att öka produktionskapaciteten av solenergi i Indien med 20 000 MW till år 2022 samt programmet Perform Ac- hieve and Trade inom ramen för strategin National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency. I dessa exempel görs observationer som är relevanta att beakta i arbe- tet med att utveckla Sveriges politik för miljöteknik, förnybar energi och minskad klimatpåverkan. Dnr 2013/104 Myndigheten för tillväxtpolitiska utvärderingar och analyser Studentplan 3, 831 40 Östersund Telefon 010 447 44 00 Telefax 010 447 44 01 E-post [email protected] www.tillvaxtanalys.se För ytterligare information kontakta Martin Flack Telefon 010 447 44 77 E-post [email protected] INNOVATION AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION IN INDIAN ENERGY POLICY Förord Förnybar energi och energieffektivisering utgör två hörnstenar i politiken för en mer håll- bar utveckling. I Europa, och i Sverige, är målsättningen att 20 procent av EU:s energikon- sumtion ska komma från förnybara källor år 2020 och andelen biodrivmedel ska samma år vara minst 10 procent. Dessutom ska EU nå ett mål om 20 procents energieffektivisering till år 2020. I snabbväxande länder som Kina, Indien och Brasilien är tillgången till billig och säker energi en förutsättning för fortsatt ekonomisk utveckling och här ses den förnybara ener- gin, liksom energieffektivisering, som ett sätt av diversifiera energimixen och minska be- roendet av fossila bränslen. Trots till viss del skilda motiv pågår i såväl Europa som i de snabbväxande ekonomierna ett intensivt arbete för att utforma insatser och styrmedel med syfte att skapa incitaments- strukturer som befrämjar investeringar i utveckling och implementering av ny energitek- nik. -

Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program Hilary Kao

William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review Volume 37 | Issue 2 Article 4 Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program Hilary Kao Repository Citation Hilary Kao, Beyond Solyndra: Examining the Department of Energy's Loan Guarantee Program, 37 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol'y Rev. 425 (2013), http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol37/iss2/4 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr BEYOND SOLYNDRA: EXAMINING THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY’S LOAN GUARANTEE PROGRAM HILARY KAO* ABSTRACT In the year following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011, the renewable and clean energy industries faced significant turmoil— from natural disasters, to political maelstroms, from the Great Recession, to U.S. debt ceiling debates. The Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program (“DOE LGP”), often a target since before it ever received a dollar of appropriations, has been both blamed and defended in the wake of the bankruptcy filing of Solyndra, a California-based solar panel manufac- turer, in September 2011, because of the $535 million loan guarantee made to it by the Department of Energy (“DOE”) in 2009.1 Critics have suggested political favoritism in loan guarantee awards and have questioned the government’s proper role in supporting renewable energy companies and the renewable energy industry generally.2 This Article looks beyond the Solyndra controversy to examine the origin, structure and purpose of the DOE LGP. It asserts that loan guaran- tees can serve as viable policy tools, but require careful crafting to have the potential to be effective programs. -

Making Renewable Energy Markets Work Citizens.” Amber Rudd, Secretary of State for the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC)

K INDIA – UK KEY MESSAGES ENERGY FOR GROWTH PARTNERSHIP “The UK and India have much in common in our pursuit for secure, affordable and sustainable energy for our Making Renewable Energy Markets Work citizens.” Amber Rudd, Secretary of State for the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) “India and UK are natural energy partners and deeper engagement can lead to a win for both” Piyush Goyal, Union Minister of State for Power, Coal, New & Renewable Energy Joint investments on solar energy R&D are being made to harness Indo-UK science and technology expertise for a better future. Renewable energy (RE) is key to mitigating emissions and supporting green Declared during India-UK Tech Summit, 2016 growth. In 2015, India enhanced its RE target to 175GW by 2022 supported by a concrete and comprehensive roadmap of policy and regulatory reforms, market-support, detailing technology need and bilateral and global India’s offshore wind power policy is expected to open new cooperation. The emphasis is now on achieving this target through market frontier for RE markets with the creation to develop a vibrant renewable energy business climate. first bidding round coming up by 2018 India’s 2022 Renewable Energy Targets Awareness building among decision makers and lenders on de-risking across the renewable value chain is key to opening more markets. Monitoring, reflecting and sharing of results achieved and lessons learned is key to scaling- up green energy opportunities. The India - UK bilateral relationship has focused on renewable energy for the past decade, starting from building sub- national capacity among state legislators, to deployment of off-grid solutions and developing risk guarantee frameworks - to enhance private investment, and the development of Indian offshore wind market. -

Assessment of Solar Thermal Power Generation Potential in India.Pdf

Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 42 (2015) 902–912 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rser Assessment of solar thermal power generation potential in India Chandan Sharma, Ashish K. Sharma, Subhash C. Mullick, Tara C. Kandpal n Centre for Energy Studies, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, Hauz Khas, New Delhi 110016, India article info abstract Article history: Realistic assessment of utilization potential of solar energy for thermal power generation and identification of Received 12 July 2014 niche areas/locations for this purpose is critically important for designing and implementing appropriate Received in revised form policies and promotional measures. This paper presents the results of a detailed analysis undertaken for 9 September 2014 estimating the potential of solar thermal power generation in India. A comprehensive framework is developed Accepted 20 October 2014 that takes into account (i) the availability of wastelands (ii) Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) (iii) wastelands that are habitat to endangered species and/or tribal population and/or that is prone to earthquakes and (iv) Keywords: suitability of wasteland for wind power generation. Finally, using an approach developed for the allocation of Solar thermal power generation wastelands suitable for solar power generation between thermal and photovoltaic routes, the potential of solar Concentrated Solar Power thermal power generation is assessed for two threshold values of DNI – 1800 kW h/m2 and 2000 kW h/m2. Potential Estimation for India With all the wastelands having wind speeds of 4 m/s or more allocated for wind power generation, the estimated potential for solar thermal power generation is 756 GW for a threshold DNI value of 1800 kW h/m2 and 229 GW for a threshold DNI value of 2000 kW h/m2. -

THE ASIA-PACIFIC 02 | Renewable Energy in the Asia-Pacific CONTENTS

Edition 4 | 2017 DLA Piper RENEWABLE ENERGY IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC 02 | Renewable energy in the Asia-Pacific CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................04 Australia ..........................................................................................08 People’s Republic of China ..........................................................17 Hong Kong SAR ............................................................................25 India ..................................................................................................31 Indonesia .........................................................................................39 Japan .................................................................................................47 Malaysia ...........................................................................................53 The Maldives ..................................................................................59 Mongolia ..........................................................................................65 Myanmar .........................................................................................72 New Zealand..................................................................................77 Pakistan ...........................................................................................84 Papua New Guinea .......................................................................90 The Philippines ...............................................................................96 -

Cadmium Telluride Photovoltaics - Wikipedia 1 of 13

Cadmium telluride photovoltaics - Wikipedia 1 of 13 Cadmium telluride photovoltaics Cadmium telluride (CdTe) photovoltaics describes a photovoltaic (PV) technology that is based on the use of cadmium telluride, a thin semiconductor layer designed to absorb and convert sunlight into electricity.[1] Cadmium telluride PV is the only thin film technology with lower costs than conventional solar cells made of crystalline silicon in multi-kilowatt systems.[1][2][3] On a lifecycle basis, CdTe PV has the smallest carbon footprint, lowest water use and shortest energy payback time of any current photo voltaic technology. PV array made of cadmium telluride (CdTe) solar [4][5][6] CdTe's energy payback time of less than a year panels allows for faster carbon reductions without short- term energy deficits. The toxicity of cadmium is an environmental concern mitigated by the recycling of CdTe modules at the end of their life time,[7] though there are still uncertainties[8][9] and the public opinion is skeptical towards this technology.[10][11] The usage of rare materials may also become a limiting factor to the industrial scalability of CdTe technology in the mid-term future. The abundance of tellurium—of which telluride is the anionic form— is comparable to that of platinum in the earth's crust and contributes significantly to the module's cost.[12] CdTe photovoltaics are used in some of the world's largest photovoltaic power stations, such as the Topaz Solar Farm. With a share of 5.1% of worldwide PV production, CdTe technology accounted for more than half of the thin film market in 2013.[13] A prominent manufacturer of CdTe thin film technology is the company First Solar, based in Tempe, Arizona. -

Policy Approaches for a Kerosene to Solar Subsidy Swap in India

Policy Approaches for a Kerosene to Solar Subsidy Swap in India REPORT Tara Laan Balasubramanian Viswanathan Chris Beaton Martand Shardul Bigsna Gill Debajit Palit © 2019 International Institute for Sustainable Development | IISD.org/gsi April 2019 Policy Approaches for a Kerosene to Solar Subsidy Swap in India © 2019 The International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development. International Institute for Sustainable Development The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is an Head Office independent think tank championing sustainable solutions to 21st– 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 century problems. Our mission is to promote human development and Winnipeg, Manitoba environmental sustainability. We do this through research, analysis and Canada R3B 0T4 knowledge products that support sound policy-making. Our big-picture Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 view allows us to address the root causes of some of the greatest challenges Website: www.iisd.org facing our planet today: ecological destruction, social exclusion, unfair laws Twitter: @IISD_news and economic rules, a changing climate. IISD’s staff of over 120 people, plus over 50 associates and 100 consultants, come from across the globe and from many disciplines. Our work affects lives in nearly 100 countries. Part scientist, part strategist—IISD delivers the knowledge to act. IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c) (3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and from the Province of Manitoba. The Institute receives project funding from numerous governments inside and outside Canada, United Nations agencies, foundations, the private sector and individuals. -

AS You Sow on Creating Greener Solar PV Panels

AS You Sow on Creating Greener Solar PV Panels Andrew Burger. March 28, 2012 Advocating solar PV manufacturers adopt a set of industry best practices, a new survey and report highlights the environmental benefits of using solar photovoltaic (PV) energy as compared to fossil fuels, while at the same time criticizing ongoing, outsized government support for fossil fuel production. “Even though there are toxic compounds used in the manufacturing of many solar panels, the generation of electricity from solar energy is much safer to both the environment and workers than production of electricity from coal, natural gas, or nuclear,” stated Amy Galland, PhD and research director at non-profit group As You Sow. “For example, once a solar panel is installed, it generates electricity with no emissions of any kind for decades, whereas coal-fired power plants in the U.S. emitted nearly two billion tons of carbon dioxide and millions of tons of toxic compounds in 2010 alone.” Based on an international survey of more than 100 solar PV manufac- turers, the best practices in As You Sow’s report, “Clean & Green: Best Practices in Photovoltaics” aim to protect the employee and community health and safety, as well as the broader environment. Also analyzed are investor considerations regarding environmental, social and govern- ance for responsible management of solar PV manufacturing business- es. The best practices listed were determined in consultation with sci- entists, engineers, academics, government labs and industry consult- ants. Solar PV CSR survey and report card “We have been working with solar companies to study and minimize the environmental health and safety risks in the production of solar panels and the industry has embraced the opportunities,” Vasilis Fthenakis, PhD and director of the National PV Environmen- tal Health and Safety Research Center at Brookhaven National Laboratory and director of the Center for Life Cycle Analysis at Columbia University, explained. -

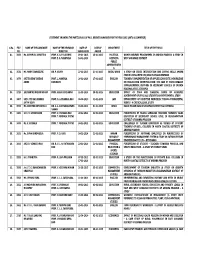

STATEMENT SHOWING the PARTICULARS of Ph.D. DEGREES AWARDED for the YEAR 2015 (ARTS & COMMERCE) S.No. FILE NO. NAME of the CA

STATEMENT SHOWING THE PARTICULARS OF Ph.D. DEGREES AWARDED FOR THE YEAR 2015 (ARTS & COMMERCE) S.No. FILE NAME OF THE CANDIDATE NAME OF THE RESEARCH DATE OF DATE OF DEPARTMENT TITLE OF THE THESIS NO. DIRECTOR SUBMISSION AWARD 01. 3493 Ms. GUNUPUDI SUNEETHA PROF. K. A. P. LAKSHMI 09-01-2013 13-01-2015 POLITICAL WOMEN WELFARE PROGRAMMES IN ANDHRA PRADESH: A STUDY IN PROF. E. A. NARAYANA 14-02-2014 SCIENCE & WEST GODAVARI DISTRICT PUBLIC ADMINISTRATIO N 02. 3532 MS. MARY EVANGELINE DR. P. ARJUN 27-02-2013 21-01-2015 SOCIAL WORK A STUDY ON CRISIS INTERVENTION AND COPING SKILLS AMONG PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV/AIDS IN VISAKHAPATNAM 03. 3679 SRI TESSEMA TADESSE PROF. L. MANJULA 26-02-2014 27-01-2015 ENGLISH TEACHERS’ IMPLEMENTATION OF APPLIED LINGUISTICS KNOWLEDGE ABEBE DAVIDSON IN FACILITATING COMMUNICATION: THE CASE OF USING ENGLISH SUPRASEGMENTAL FEATURES IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS OF OROMIA REGIONAL STATE, ETHIOPIA 04. 3719 SRI MANTRI MADAN MOHAN PROF. GARA LATCHANNA 26-05-2014 30-01-2015 EDUCATION IMPACT OF YOGA AND CLASSICAL DANCE ON ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT OF 9TH CLASS STUDENTS AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY 05. 3607 SRI C. TEJ RAJ SHARMA PROF. D. S. PRAKASA RAO 06-09-2013 31-01-2015 LAW ENFORCEMENT OF DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES THROUG FUNDAMENTAL SATYA VIJAY RIGHTS - A CRITICAL LEGAL STUDY 06. 3725 MS. SUMITRA KOTHAPALLI DR. S. A. SURYANARAYANA 03-06-2014 31-01-2015 HINDI RAAHI MASUM RAJA KE UPANYASON MEIN YUG CHETHANA VARMA 07. 3483 Sri E. V. SATISH BABU PROF. D. PRAKASA RAO 28-12-2012 31-01-2015 EDUCATION PERCEPTIONS OF TELUGU LANGUAGE TEACHERS TOWARDS VALUE PROF.