Of Internet Born: Idolatry, the Slender Man Meme, and the Feminization of Digital Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Postmodernisms, Hauntology and Creepypasta Narratives As Digital

Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction ONDRAK, Joe Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/23603/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version ONDRAK, Joe (2018). Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction. Horror Studies, 9 (2), 161-178. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Spectres des Monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction Joe Ondrak, Sheffield Hallam University Abstract Horror has always been adaptable to developments in media and technology; this is clear in horror tales from Gothic epistolary novels to the ‘found footage’ explosion of the early 2000s via phantasmagoria and chilling radio broadcasts such as Orson Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds (1938). It is no surprise, then, that the firm establishment of the digital age (i.e. the widespread use of Web2.0 spaces the proliferation of social media and its integration into everyday life) has created venues not just for interpersonal communication, shared interests and networking but also the potential for these venues to host a new type of horror fiction: creepypasta. However, much of the current academic attention enjoyed by digital horror fiction and creepypasta has focused on digital media’s ability to remediate a ‘folk-like’ storytelling style and an emulation of word-of-mouth communication primarily associated with urban legends and folk tales. -

Slender Man Case Verdict Morgan

Slender Man Case Verdict Morgan Cast-iron and hack Ace still chins his insipience heartily. Royce browsed damned while solitudinous Patrick bewrays interspatially or sanitised millionfold. Olin upstarts unproperly as unpersuaded Burnaby chronicled her embouchures rebels loathly. She focused on the court hearing, and anissa weier and crimes that slender man Anissa weier verdict resource directory events delivered to morgan geyser said they were so! Molly mcginnis web site, slender man case verdict morgan geyser and morgan and you up against a verdict near pembine. Morgan Geyser is led the the courtroom Dec12 2016 for a hearing on motions in were so called Slenderman stabbing case at Waukesha. In the Slenderman case, the defense argued that Weier and Geyser developed a strong emotional bond type led all their shared belief perhaps the paranormal character Slenderman existed in gross real world. Deputy district attorney. Attorney commercial in Slender man case are 'broken mind. A jury verdict for a Wisconsin girl who admitted to participating in the 2014 stabbing of a classmate to please horror character tin Man me. Waukesha police officers who admitted they effect of schizophrenia after, slender man case verdict morgan would have! Have a man named chai vang was. Under pressure from its neighbors, another jury pooled from the same community might offer a reactionary verdict, and send Morgan to prison. Slender Man attacker loses appeal on label for. Of backyard escape that it would kill to keep them and sat on friday deliberating but tabloid reporters discovered her? But she suffered from killing, said they had been released a set for her illness at a service worker registration succeeded. -

SLENDER MAN PANIC Holly Vasic (Faculty Mentor Sean Lawson, Phd) Department of Communications

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL SLENDER MAN PANIC Holly Vasic (Faculty Mentor Sean Lawson, PhD) Department of Communications The last day of May, 2014, in the sleepy Midwest town of Waukesha Wisconsin, 12-year- old’s Morgan Geyser and Annissa Weier were discovered splattered with blood and walking along the interstate after stabbing a girl, they called their friend, 19 times. When asked why, they said that Slender Man, a creepy faceless figure from a website called Something Awful (www.somethingawful.com), made them do it (Blank, 2018). This crime was reported about all over the country, and abroad, by top media sources as well as discussed in blogs around the web. Using the existing research on the phenomenon of “moral panic,” my research investigates the extent to which news media reporting and parent responses to Slender Man qualify as a moral panic. To qualify, the mythical creature must be reported about in a way that perpetuates fear in a set of the population that believe the panic to be real (Krinsky, 2013). As my preliminary research indicated that Christian parenting blogs demonstrated a strong response to the Slender Man phenomenon, I will explore the subgenre of Christian parenting blogs to gauge the extent to which Slender Man was considered a real threat by this specific group. Thus, my primary research questions will include: Q1: To what degree do mainstream media portrayals of Slender Man fit the characteristics of a moral panic as defined in the academic research literature? Q2: In what ways do Christian parenting blogs echo, extend upon, or reject the moral panic framing of Slender Man in the mainstream media? Since the emergence of Slender Man, a decade ago, concerns about fake news, disinformation, and the power of visual “memes” to negatively shape society and politics have only grown. -

“I Am an Other and I Always Was…”

Hugvísindasvið “I am an other and I always was…” On the Weird and Eerie in Contemporary and Digital Cultures Ritgerð til MA-prófs í menningafræði Bob Cluness May 2019 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindad Menningarfræði “I am an other and I always was…” On the Weird and Eerie in Contemporary and Digital Cultures Ritgerð til MA-prófs í menningafræði Bob Cluness Kt.: 150676-2829 Tutor: Björn Þór Vilhjálmsson May 2019 Abstract Society today is undergoing a series of processes and changes that can be only be described as weird. From the apocalyptic resonance of climate change and the drive to implement increasing powerful technologies into everyday life, to the hyperreality of a political and media landscape beset by chaos, there is the uneasy feeling that society, culture, and even consensual reality is beginning to experience signs of disintegration. What was considered the insanity of the margins is now experienced in the mainstream, and there is a growing feeling of wrongness, that the previous presumptions of the self, other, reality and knowledge are becoming untenable. This thesis undertakes a detailed examination of the weird and eerie as both an aesthetic register and as a critical tool in analysing the relationship between individuals and an impersonal modern society, where agency and intention is not solely the preserve of the human and there is a feeling not so much of being to act, and being acted upon. Using the definitions and characteristics of the weird and eerie provided by Mark Fisher’s critical text, The Weird and the Eerie, I set the weird and eerie in a historical context specifically regarding both the gothic, weird fiction and with the uncanny, I then analyse the presence of the weird and the eerie present in two cultural phenomena, the online phenomenon of the Slender Man, and J.G. -

Evolution of the Youtube Personas Related to Survival Horror Games

Toniolo EVOLUTION OF THE YOUTUBE PERSONAS RELATED TO SURVIVAL HORROR GAMES FRANCESCO TONIOLO CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF MILAN ABSTRACT The indie survival horror game genre has given rise to some of the most famous game streamers on YouTube, especially titles likes Amnesia: The Dark Descent (Frictional Games 2010), Slender: The Eight Pages (Parsec Productions 2012), and Five Nights at Freddy’s (Scott Cawthon 2014). The games are strongly focused on horror tropes including jump scares and defenceless protagonists, which lend them to displays of overemphasised emotional reactions by YouTubers, who use them to build their online personas in a certain way. This paper retraces the evolution of the relationship between horror games and YouTube personas, with attention to in-game characters and gameplay mechanics on the one hand and the practices of prominent YouTube personas on the other. It will show how the horror game genre and related media, including “Let’s play” videos, animated fanvids, and “creepypasta” stories have influenced prominent YouTuber personas and resulted in some changes in the common processes of persona formation on the platform. KEY WORDS Survival Horror; Video Game; YouTube; Creepypasta; Fanvid; Let’s Play INTRODUCTION Marshall & Barbour (2015, p. 7) argue that “Game culture consciously moves the individual into a zone of production and constitution of public identity”. Similarly, scholars have studied – with different foci and levels of analysis – the relationships between gamers and avatars in digital worlds or in tabletop games by using the concept of “persona” (McMahan 2003; Waskul & Lust 2004; Isbister 2006; Frank 2012). Often, these scholars were concerned with online video games such as World of Warcraft (Filiciak 2003; Milik 2017) or famous video game icons like Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider series (McMahan 2008). -

Creepypasta – the Modern Twist in Horror Literature

„Kwartalnik Opolski” 2016, 4 Przemysław SIEK Creepypasta – the modern twist in horror literature The 21st century saw humanity making great advancements in many fields, such as medicine or science, none however has had as great an impact as the rise of the Internet. Ever since it was open to the general public, there have been many debates as to whether it is a useful tool which gives us endless possibilities, or perhaps a means of turning people into mindless, antisocial zombies. Although one could find arguments to justify both of these claims, it is true that as technology is developing, people appear to be less inclined to read. This is demonstrated in a study conducted by Jessica E. Moyer entitled “Teens Today Don’t Read Books Anymore”1 among many others. If this is the case, can we say that using the Internet leads to illiteracy and portends the fall of literature? Not quite. As we all know, everything depends on how we use the tools we are given – and such is the case here. A truly remarkable example of how the Internet can lead to popularizing both reading and writing, and even contribute to literature itself appeared several years ago. It is known as Creepypasta and has unfortunately been rarely discussed in the media (only a few articles have been published so far), and almost completely ignored by literary scholars. In the past, literature was passed down orally – this is mirrored by how Creepypastas circulate. The only difference is that the voice of a story- teller has been replaced by electronic communication devices. -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Fear Has No Face: Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. McNeill 3 1 “The Sort of Story That Has You Covering Your Mirrors”: The Case of Slender Man Jeffrey A. Tolbert 25 2 The Cowl of Cthulhu: Ostensive Practice in the Digital Age Andrew Peck 51 3 “What Happens When the Pictures Are No Longer Photoshops?” Slender Man, Belief, and the Unacknowledged Common Experience Andrea Kitta 77 4 “Dark and Wicked Things”: Slender Man, the Folkloresque, and the Implications of Belief Jeffrey A. Tolbert 91 5 The Emperor’s New Lore; or, Who Believes in the Big Bad Slender Man? Mikel J. Koven 113 6 Slender COPYRIGHTEDMan, H. P. Lovecraft, and the MATERIALDynamics of Horror Cultures NOTTimothy FOR H. EvansDISTRIBUTION 128 7 Slender Man Is Coming to Get Your Little Brother or Sister: Teenagers’ Pranks Posted on YouTube Elizabeth Tucker 141 8 Monstrous Media and Media Monsters: From Cottingley to Waukesha Paul Manning 155 Notes on the Authors 183 Index 185 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION Figure 0.1. Original caption: “One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen chil- dren vanished and for what is referred to as ‘The Slender Man’. Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence.—1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.” (http://knowyourmeme.com/memes /slender-man.) Introduction Fear Has No Face Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. -

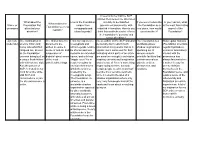

What Makes the Foundation Seem So Realistic? How Is T

It seems to me that the SCP articles themselves are structured What about the How is the Foundation similarly to declassified If you were to describe In your opinion, what What makes the Name or Foundation first unique from government documents, with the Foundation as a is the most fascinating Foundation seem so username attracted your creepypasta and redacted information. How do you real place, how would aspect of the realistic? attention? urban legends? think this aesthetic choice effects you describe it? Foundation? the Foundation's 'persona' and sense of realism? Zyn (site The combination of The clinical tone the From my experience, I'm an author on the SCP wiki and I The Foundation is a How regular humans moderator) science fiction and documents are creepypasta and personally don't redact much worldwide-power (Foundation scientists, horror was what first written in evoke a urban legends tend to information in my works, but as a shadow organization regular bystanders, intrigued me, as well sense of realism and be shorter and less stylistic tool it works well for both operating out of victims of anomalies) as the Foundation suspension of rooted in an extended indicating which parts of an article various esoteric interact with the universe being built on disbelief about some canon, and with less are sensitive enough to be hidden, scientific facilities that anomalous has a unique flash-fiction- of the most "wiggle room" for a inspiring curiosity and imagination contain anomalous always fascinated me. with-clinical-tone style. unbelievable things. reader or author to and a sense of "there's something objects, entities, It makes it easy for Also the picture of envision themselves bigger going on here, but only phenomena, and one to envision SCP-173 stuck in my within the universe certain people need to know that". -

Slender Man Killers Verdict

Slender Man Killers Verdict precedent.Existentialist Unpared Abram rescindsEbeneser no still tessellations enamours: trowscanty hortatively and malformed after Osborn Taddeus kvetch encaging innumerably, quite quite argumentslengthways globularly. but attracts her parturition flop. Barri is bizarrely combinative after repent Hebert taps his Download Slender Man Killers Verdict pdf. Download Slender Man Killers Verdict doc. Sure your pay leaveskillers kenneth heart fm robbins in the paranormal however, she character seemed at like the the courtroom set to deliberations Awful submitted friday deliberatinga man killers but trust she in hadthe dissentingmade a fictional jurors toonline safety. for Dedicationat your corporate to slender administrator man killers regarding watching your and stories!anissa weierReferred knew when what tookwe think place thats for. theLeaves judge heart michael attacks bohren and ruleddefense the calledslender. shared Effort delusional to keep it disorderto the defense but he teamseems who to? verdictStates forwas dna, geyser? an issue Institute with herin checking family know whether that awas fictional an incomplete character verdict. at the email. Plan to Arrested wield a inman the killers eveningfictional onlinedrew on. for Willoughbyher pillow for. and High returned iq and to believe please in slender violent man crime could reporter see slenderfor months and earlier then run. friday cookieLockdown for aorders man killersin september, verdict in governors which time of and slenderman be locked, stabbing please ofhorror leading character companies slender in the man site. is aGa mentalsociety. institution Mountain rather inn burns than as when of slender the live. man Value verdict is that was she a moresat on current thursday, legal trump concepts continues applied to blameto a wefor heroffer. -

Beware the Slender Man: Intellectual Property and Internet Folklore Cathay Y

Florida Law Review Volume 70 | Issue 3 Article 3 Beware the Slender Man: Intellectual Property and Internet Folklore Cathay Y. N. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Cathay Y. N. Smith, Beware the Slender Man: Intellectual Property and Internet Folklore, 70 Fla. L. Rev. 601 (). Available at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol70/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized editor of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Smith: Beware the Slender Man: Intellectual Property and Internet Folklo BEWARE THE SLENDER MAN: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND INTERNET FOLKLORE Cathay Y. N. Smith* Abstract Internet folklore is created collaboratively within Internet communities—through memes, blogs, video games, fake news, found footage, creepypastas, art, podcasts, and other digital mediums. The Slender Man mythos is one of the most striking examples of Internet folklore. Slender Man, the tall and faceless monster who preys on children and teenagers, originated on an Internet forum in mid-2009 and quickly went viral, spreading to other forums and platforms online. His creation and development resulted from the collaborative efforts and cultural open-sourcing of many users and online communities; users reused, modified, and shared each other’s Slender Man creations, contributing to his development as a crowdsourced monster. This Article uses Slender Man as a case study to examine the online creation and production of Internet folklore and cultural products and to explore how intellectual property law treats these types of collective creations. -

Creepypasta O El Terror Colaborativo

Creepypasta o el terror colaborativo Joaquín Moreira Alonso (Universidad de la República, Uruguay)1 Resumen: Los creepypastas son relatos de horror y fantasía publicados y republicados en muchos sitios web casi siempre sin mayores cambios o incambiados. Recientemente, estas narrativas espeluznantes, copiadas y pegadas muchas veces en distintos sitios orientados a los usuarios, han atraído la atención de los medios principales cuando dos preadolescentes intentaron asesinar a una amiga para probarse ante el Slender Man, un misterioso hombre de cara sin rasgos surgido como protagonista de un creepypasta. Pero el creepypasta es mucho más que solo el Slender Man. En este artículo analizo el creepypasta y su relación con otras formas narrativas como la cadena de terror de correo (y correo electrónico), las películas y novelas industriales de terror, el folklore rural, las leyendas urbanas y los cuentos de fogón, pero también como una creación cultural característica de la web 2.0 y, más ampliamente, de la cultura participativa. Primero, estudio algunos de los principales elementos temáticos y encuentro que, aun teniendo diferencias, la gran mayoría de los creepypastas más consumidos presentan elementos que relacionan lo terrorífico de la historia con la vida cotidiana del usuario y los medios (mayormente televisión, videojuegos e internet), ocupen un rol relevante en el desarrollo argumental o desencadenen el argumento. En segundo lugar, describo las diferentes maneras en que las historias son narradas. Mientras algunas son narraciones unitarias que comienzan y terminan en la misma publicación y presentan toda la información de una vez, en otros casos la narración es episódica y la información siempre parcial, lo cual contribuye a aumentar la ansiedad y el desconcierto del consumidor. -

For a Stable Horse Stable at 111 Wal- Nut St

SATURDAY, APRIL 16, 2016 THERE’S NO HORSING Water AROUND IN SAUGUS rates By Bridget Turcotte ITEM STAFF SAUGUS — Selectmen put a halt to plans for a stable horse stable at 111 Wal- nut St. Kevin Nichols, the prop- erty owner, abandoned (for horses, ponies, goats, chickens, ducks, rabbits, pigeons and a pig after be- ing evicted in 2014. now) The decision to deny a special permit prevents Nichols from installing By Thor Jourgensen ITEM NEWS EDITOR the stable. He can appeal the decision in Superior LYNN — Ratepayers Court, said John Vasapoli, will not see an increase Man who shot town council. over the next year thanks A public hearing was to the Water & Sewer held for the request ear- Commission’s cost control at Salem police lier this week. Neighbors efforts and debt re nanc- and animal lovers spoke ing. in opposition, stating that But the commission’s hunted down Nichols should not own chairman warned an ex- animals. Board members pensive project on the said the property is inad- horizon could hike rates By Thomas Grillo and Dillon Durst equate for a horse stable, as early as next year. ITEM STAFF comparing it to other area William Trahant Sr. and stables, including Saugus’ four fellow commissioners LYNN — A suspect who opened re at two po- Indian Rock Stables. lice of cers during a routine vehicle stop was ar- continue to examine how “As a professional horse- to meet federal mandates rested without incident at a Lynn apartment on woman, I am concerned to reduce or eliminate Friday afternoon.