• Articles • Using the Library of Congress' Web Cultures Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hair: the Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960S’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Winchester Research Repository University of Winchester ‘Hair: The Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960s’ Sarah Elisabeth Browne ORCID: 0000-0003-2002-9794 Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester MPhil/PhD THESES OPEN ACCESS / EMBARGO AGREEMENT FORM This Agreement should be completed, signed and bound with the hard copy of the thesis and also included in the e-copy. (see Thesis Presentation Guidelines for details). Access Permissions and Transfer of Non-Exclusive Rights By giving permission you understand that your thesis will be accessible to a wide variety of people and institutions – including automated agents – via the World Wide Web and that an electronic copy of your thesis may also be included in the British Library Electronic Theses On-line System (EThOS). Once the Work is deposited, a citation to the Work will always remain visible. Removal of the Work can be made after discussion with the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, who shall make best efforts to ensure removal of the Work from any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement. Agreement: I understand that the thesis listed on this form will be deposited in the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, and by giving permission to the University of Winchester to make my thesis publically available I agree that the: • University of Winchester’s Research Repository administrators or any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement to do so may, without changing content, translate the Work to any medium or format for the purpose of future preservation and accessibility. -

Post-Postmodernisms, Hauntology and Creepypasta Narratives As Digital

Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction ONDRAK, Joe Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/23603/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version ONDRAK, Joe (2018). Spectres des monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction. Horror Studies, 9 (2), 161-178. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Spectres des Monstres: Post-postmodernisms, hauntology and creepypasta narratives as digital fiction Joe Ondrak, Sheffield Hallam University Abstract Horror has always been adaptable to developments in media and technology; this is clear in horror tales from Gothic epistolary novels to the ‘found footage’ explosion of the early 2000s via phantasmagoria and chilling radio broadcasts such as Orson Welles’ infamous War of the Worlds (1938). It is no surprise, then, that the firm establishment of the digital age (i.e. the widespread use of Web2.0 spaces the proliferation of social media and its integration into everyday life) has created venues not just for interpersonal communication, shared interests and networking but also the potential for these venues to host a new type of horror fiction: creepypasta. However, much of the current academic attention enjoyed by digital horror fiction and creepypasta has focused on digital media’s ability to remediate a ‘folk-like’ storytelling style and an emulation of word-of-mouth communication primarily associated with urban legends and folk tales. -

Marble Hornets, the Slender Man, and the Emergence Of

DIGITAL FOLKLORE: MARBLE HORNETS, THE SLENDER MAN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF FOLK HORROR IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Dana Keller B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Dana Keller, 2013 Abstract In June 2009 a group of forum-goers on the popular culture website, Something Awful, created a monster called the Slender Man. Inhumanly tall, pale, black-clad, and with the power to control minds, the Slender Man references many classic, canonical horror monsters while simultaneously expressing an acute anxiety about the contemporary digital context that birthed him. This anxiety is apparent in the collective legends that have risen around the Slender Man since 2009, but it figures particularly strongly in the Web series Marble Hornets (Troy Wagner and Joseph DeLage June 2009 - ). This thesis examines Marble Hornets as an example of an emerging trend in digital, online cinema that it defines as “folk horror”: a subgenre of horror that is produced by online communities of everyday people— or folk—as opposed to professional crews working within the film industry. Works of folk horror address the questions and anxieties of our current, digital age by reflecting the changing roles and behaviours of the everyday person, who is becoming increasingly involved with the products of popular culture. After providing a context for understanding folk horror, this thesis analyzes Marble Hornets through the lens of folkloric narrative structures such as legends and folktales, and vernacular modes of filmmaking such as cinéma direct and found footage horror. -

Broadway 1 a (1893-1927) BROADWAY and the AMERICAN DREAM

EPISODE ONE Give My Regards to Broadway 1 A (1893-1927) BROADWAY AND THE AMERICAN DREAM In the 1890s, immigrants from all over the world came to the great ports of America like New York City to seek their fortune and freedom. As they developed their own neighborhoods and ethnic enclaves, some of the new arrivals took advantage of the stage to offer ethnic comedy, dance and song to their fellow group members as a much-needed escape from the hardships of daily life. Gradually, the immigrants adopted the characteristics and values of their new country instead, and their performances reflected this assimilation. “Irving Berlin has no place in American music — he is American music.” —composer Jerome Kern My New York (excerpt) Every nation, it seems, Sailed across with their dreams To my New York. Every color and race Found a comfortable place In my New York. The Dutchmen bought Manhattan R Island for a flask of booze, E V L U C Then sold controlling interest to Irving Berlin was born Israel Baline in a small Russian village in the Irish and the Jews – 1888; in 1893 he emigrated to this country and settled in the Lower East Side of And what chance has a Jones New York City. He began his career as a street singer and later turned to With the Cohens and Malones songwriting. In 1912, he wrote the words and music to “Alexander’s Ragtime In my New York? Band,” the biggest hit of its day. Among other hits, he wrote “Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,” “What’ll I Do?,” “There’s No Business Like —Irving Berlin, 1927 Show Business,” “Easter Parade,” and the patriotic “God Bless America,” in addition to shows like Annie Get Your Gun. -

Evolution of the Youtube Personas Related to Survival Horror Games

Toniolo EVOLUTION OF THE YOUTUBE PERSONAS RELATED TO SURVIVAL HORROR GAMES FRANCESCO TONIOLO CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF MILAN ABSTRACT The indie survival horror game genre has given rise to some of the most famous game streamers on YouTube, especially titles likes Amnesia: The Dark Descent (Frictional Games 2010), Slender: The Eight Pages (Parsec Productions 2012), and Five Nights at Freddy’s (Scott Cawthon 2014). The games are strongly focused on horror tropes including jump scares and defenceless protagonists, which lend them to displays of overemphasised emotional reactions by YouTubers, who use them to build their online personas in a certain way. This paper retraces the evolution of the relationship between horror games and YouTube personas, with attention to in-game characters and gameplay mechanics on the one hand and the practices of prominent YouTube personas on the other. It will show how the horror game genre and related media, including “Let’s play” videos, animated fanvids, and “creepypasta” stories have influenced prominent YouTuber personas and resulted in some changes in the common processes of persona formation on the platform. KEY WORDS Survival Horror; Video Game; YouTube; Creepypasta; Fanvid; Let’s Play INTRODUCTION Marshall & Barbour (2015, p. 7) argue that “Game culture consciously moves the individual into a zone of production and constitution of public identity”. Similarly, scholars have studied – with different foci and levels of analysis – the relationships between gamers and avatars in digital worlds or in tabletop games by using the concept of “persona” (McMahan 2003; Waskul & Lust 2004; Isbister 2006; Frank 2012). Often, these scholars were concerned with online video games such as World of Warcraft (Filiciak 2003; Milik 2017) or famous video game icons like Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider series (McMahan 2008). -

Page to Stage

PAGE TO STAGE Curriculum resources based on the extraordinary children’s classic by Roald Dahl Updated for the Australian Curriculum by Eli Erez and David Perry The World’s No. 1 Storyteller Appropriate for ages 7-12 www.qpac.com.au/event/charlie_chocolate_factory_21/ 1 LIST OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CONNECTIONS TO AUST CURRICULUM ACTIVITIES: ENGLISH VISUAL ARTS Slam Writing Unchartered Territory Diary Entry Setting the Scene Poetry in Motion Packaging Design Spotting Adjectives Create Your Own Chocolate Treat A Ride in the Glass Elevator Your Favourite Scene Which Words WORKSHEETS: THE ARTS 1. Character Cards DANCE 2. Poetry In Motion Making Moves 3. Spotting the Adjectives Discussing Dance 4. Mr Wonka’s Factory Creating Choreography 5. Character Portraits 6. Adventure Cards DRAMA 7. Structuring Your Scene 8. Who’s Involved? Character Portraits 9. Design A Mood Board What Would You Ask? 10. The Right Material Storyboarding a Scene 11. Dressing the Oompa-Loompas The Final Chapter 12. Read All About It Who’s Involved 13. Create Your Own Chocolate Treat The Right Material 14. Design A Chocolate Bar Wrapper Dressing the Oompa-Loompas (Parts 1, 2 & 3) 15. Design Your Own Packaging MEDIA ARTS Read All About It ADDITIONAL RESOURCES: Design an Ad Biographies of the Cast & Creative Team Spread the Word Synopsis Where Are They Now? Character Descriptions Wonka Promo Ad Other Resources MUSIC Be a Broadway Songwriter Have a Good Time with Rhyme Call and Response Special Effects The Oompa-Loompa Song 2 WELCOME TO THE WONDROUS WORLD OF THE MAJOR NEW STAGE MUSICAL Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the deliciously dark children’s classic, has been turned into a brand-new musical from three-time Tony Award© winning director Jack O’Brien and the Grammy© and Tony-winning songwriters of Hairspray: Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman. -

Creepypasta – the Modern Twist in Horror Literature

„Kwartalnik Opolski” 2016, 4 Przemysław SIEK Creepypasta – the modern twist in horror literature The 21st century saw humanity making great advancements in many fields, such as medicine or science, none however has had as great an impact as the rise of the Internet. Ever since it was open to the general public, there have been many debates as to whether it is a useful tool which gives us endless possibilities, or perhaps a means of turning people into mindless, antisocial zombies. Although one could find arguments to justify both of these claims, it is true that as technology is developing, people appear to be less inclined to read. This is demonstrated in a study conducted by Jessica E. Moyer entitled “Teens Today Don’t Read Books Anymore”1 among many others. If this is the case, can we say that using the Internet leads to illiteracy and portends the fall of literature? Not quite. As we all know, everything depends on how we use the tools we are given – and such is the case here. A truly remarkable example of how the Internet can lead to popularizing both reading and writing, and even contribute to literature itself appeared several years ago. It is known as Creepypasta and has unfortunately been rarely discussed in the media (only a few articles have been published so far), and almost completely ignored by literary scholars. In the past, literature was passed down orally – this is mirrored by how Creepypastas circulate. The only difference is that the voice of a story- teller has been replaced by electronic communication devices. -

Of Internet Born: Idolatry, the Slender Man Meme, and the Feminization of Digital Spaces

Feminist Media Studies ISSN: 1468-0777 (Print) 1471-5902 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfms20 Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces Jessica Maddox To cite this article: Jessica Maddox (2018) Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces, Feminist Media Studies, 18:2, 235-248, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 Published online: 15 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 556 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfms20 FEMINIST MEDIA STUDIES, 2018 VOL. 18, NO. 2, 235–248 https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1300179 Of Internet born: idolatry, the Slender Man meme, and the feminization of digital spaces Jessica Maddox Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, The University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This paper examines 96 US and British Commonwealth articles on the Received 31 May 2016 2014 Wisconsin Slender Man stabbing. Using critical textual analysis, Revised 28 October 2016 this study examined how media took a horror-themed meme from Accepted 29 January 2017 the underbelly of the Internet and curated a moral panic, once the KEYWORDS meme was thrust into the international limelight. Because memes are Memes; Internet; idolatry; a particular intersection of images and technology, media made sense Slender Man; technology; of this meme-inspired attack in three ways: (1) through an idolatrous feminism tone that played on long-standing Western anxieties over images; (2) by hyper-sensationalizing women’s so-called frivolous uses of technology; and (3) by removing blame from the assailants and, in turn, finding the Internet and the Slender Man meme guilty in the court of public opinion. -

Meeting Your Monstrous Self Thesis Proposal

Vashti Tacoronte University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus College of Arts and Sciences Department of English Meeting your Monstrous Self: Fractured Identity and Duality in the Slender Man Mythos as Seen Through EverymanHYBRID By Vashti Tacoronte Cruz © Thesis Proposal Master of Arts in English Education Vashti Tacoronte Introduction In this hybrid thesis project, I will analyze how the internet figure of Slenderman, created by Eric Knudsen under the alias of Victor surge on the Something Awful forums for a photoshop contest on June 8th 2009, and his portrayal in series like EverymanHYBRID, Marble Hornets, and Tribe Twelve exemplify the fears and anxieties modern society has towards mental illnesses like depression and bipolar disorder, as well as the feelings of loss of control that accompany these disorders. This hybrid thesis will also explore how series like EverymanHYBRID, Marble Hornets, and Tribe Twelve use the character of Slender Man as a metaphor to effectively represent mental illness, the fracture in the Self -produced through meeting the bogeyman figure of Slender Man-, and its consequent creation of duality in the form of a horrific other, because of their reliance on multimodal media that allows them to reach an audience that lives digitally. The analysis of this video series will be guided by the theoretical lens of gender studies and will present Helene Cisoux’s theory of binary opposition as the primary approach to understanding the duality present in these series, with scrupulous emphasis given to the character of Evan in EverymanHYBRID. In addition to this, the analysis will also employ a structuralist theoretical lens, noting the work of important theorists such as Claude-Levi Strauss and Michel Foucault, in order to understand the structures shaping the view of madness in society. -

GREASE • Production Overview • Lesson Guides • Student Activities • At-Home Projects • Reproducibles Copyright 2007, Camp Broadway, LLC All Rights Reserved

A tool for using the theater across the curriculum to meet National Standards for Education GREASE • Production Overview • Lesson Guides • Student Activities • At-Home Projects • Reproducibles Copyright 2007, Camp Broadway, LLC All rights reserved This publication is based on Grease with book, music and lyrics by Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey and directed and choreographed by Kathleen Marshall. The content of the Grease edition of StageNOTES™: A Field Guide for Teachers is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United states of America and all other countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights regarding publishing, reprint permissions, public readings, and mechanical or electronic reproduction, including but not limited to, CD-ROM, information storage and retrieval systems and photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America First Digital Edition: January 2008 For more information on StageNOTES™ and other theatre arts related programs, contact: Camp Broadway, LLC 336 West 37th Street, Suite 460 New York, New York 10018 Telephone: (212) 575-2929 Facsimile: (212) 575-3125 Email: [email protected] www.campbroadway.com Table of contents Using the Field Guide and Lessons...................................................................................................4 Synopsis and Character Breakdown..................................................................................................5 Overture -

Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Fear Has No Face: Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. McNeill 3 1 “The Sort of Story That Has You Covering Your Mirrors”: The Case of Slender Man Jeffrey A. Tolbert 25 2 The Cowl of Cthulhu: Ostensive Practice in the Digital Age Andrew Peck 51 3 “What Happens When the Pictures Are No Longer Photoshops?” Slender Man, Belief, and the Unacknowledged Common Experience Andrea Kitta 77 4 “Dark and Wicked Things”: Slender Man, the Folkloresque, and the Implications of Belief Jeffrey A. Tolbert 91 5 The Emperor’s New Lore; or, Who Believes in the Big Bad Slender Man? Mikel J. Koven 113 6 Slender COPYRIGHTEDMan, H. P. Lovecraft, and the MATERIALDynamics of Horror Cultures NOTTimothy FOR H. EvansDISTRIBUTION 128 7 Slender Man Is Coming to Get Your Little Brother or Sister: Teenagers’ Pranks Posted on YouTube Elizabeth Tucker 141 8 Monstrous Media and Media Monsters: From Cottingley to Waukesha Paul Manning 155 Notes on the Authors 183 Index 185 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION Figure 0.1. Original caption: “One of two recovered photographs from the Stirling City Library blaze. Notable for being taken the day which fourteen chil- dren vanished and for what is referred to as ‘The Slender Man’. Deformities cited as film defects by officials. Fire at library occurred one week later. Actual photograph confiscated as evidence.—1986, photographer: Mary Thomas, missing since June 13th, 1986.” (http://knowyourmeme.com/memes /slender-man.) Introduction Fear Has No Face Creepypasta as Digital Legendry Trevor J. Blank and Lynne S. -

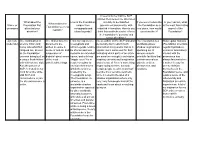

What Makes the Foundation Seem So Realistic? How Is T

It seems to me that the SCP articles themselves are structured What about the How is the Foundation similarly to declassified If you were to describe In your opinion, what What makes the Name or Foundation first unique from government documents, with the Foundation as a is the most fascinating Foundation seem so username attracted your creepypasta and redacted information. How do you real place, how would aspect of the realistic? attention? urban legends? think this aesthetic choice effects you describe it? Foundation? the Foundation's 'persona' and sense of realism? Zyn (site The combination of The clinical tone the From my experience, I'm an author on the SCP wiki and I The Foundation is a How regular humans moderator) science fiction and documents are creepypasta and personally don't redact much worldwide-power (Foundation scientists, horror was what first written in evoke a urban legends tend to information in my works, but as a shadow organization regular bystanders, intrigued me, as well sense of realism and be shorter and less stylistic tool it works well for both operating out of victims of anomalies) as the Foundation suspension of rooted in an extended indicating which parts of an article various esoteric interact with the universe being built on disbelief about some canon, and with less are sensitive enough to be hidden, scientific facilities that anomalous has a unique flash-fiction- of the most "wiggle room" for a inspiring curiosity and imagination contain anomalous always fascinated me. with-clinical-tone style. unbelievable things. reader or author to and a sense of "there's something objects, entities, It makes it easy for Also the picture of envision themselves bigger going on here, but only phenomena, and one to envision SCP-173 stuck in my within the universe certain people need to know that".