“I Am an Other and I Always Was…”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Marble Hornets, the Slender Man, and The

DIGITAL FOLKLORE: MARBLE HORNETS, THE SLENDER MAN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF FOLK HORROR IN ONLINE COMMUNITIES by Dana Keller B.A., The University of British Columbia, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Film Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Dana Keller, 2013 Abstract In June 2009 a group of forum-goers on the popular culture website, Something Awful, created a monster called the Slender Man. Inhumanly tall, pale, black-clad, and with the power to control minds, the Slender Man references many classic, canonical horror monsters while simultaneously expressing an acute anxiety about the contemporary digital context that birthed him. This anxiety is apparent in the collective legends that have risen around the Slender Man since 2009, but it figures particularly strongly in the Web series Marble Hornets (Troy Wagner and Joseph DeLage June 2009 - ). This thesis examines Marble Hornets as an example of an emerging trend in digital, online cinema that it defines as “folk horror”: a subgenre of horror that is produced by online communities of everyday people— or folk—as opposed to professional crews working within the film industry. Works of folk horror address the questions and anxieties of our current, digital age by reflecting the changing roles and behaviours of the everyday person, who is becoming increasingly involved with the products of popular culture. After providing a context for understanding folk horror, this thesis analyzes Marble Hornets through the lens of folkloric narrative structures such as legends and folktales, and vernacular modes of filmmaking such as cinéma direct and found footage horror. -

Avanessian – Xenoarchitecture (Draft) 1 Introduction Armen Avanessian

avanessian – xenoarchitecture (draft) Introduction Armen Avanessian “Man’s desire is the desire of the Other,” Lacan, Seminar XI, p. 235 Following Lacan’s infamous dictum, according to which desire is defined as the desire of the Other, we could ask ourselves what a correlate methodology would look like for the humanities (or should we say “the inhumanities”?). Obviously, the structure of the phrase is ambiguous, or even tautological if taken as a predicative proposition. Instead, I propose to read it as a speculative proposition: we do not simply desire what the other has or hasn’t got, but we desire the state of being an Other, an othering, becoming a stranger to oneself and others—literally alienating them as well as “ourselves.” A desire for the xeno? This transformation has at least three central aspects: alienation (the negative mirroring of a given reality), negation (the construction of an asymmetry that initiates an annihilation of the positively given), and a recursion of alienation and negation through speculation.1 It is a poietic qua productive and creative transformation in the sense that it increases the scope of navigation and liberation by means of manipulation. Together with others, I have thought, experimented, and written a lot about questions of othering and “matching” experimental settings2 for the production of knowledge, tactical spaces in the sense of Michel de Certeau, xeno-spaces that are defined by “a calculated action determined by the absence of a proper locus. No delimitation of an exteriority, then, provides it with the condition necessary for autonomy. The space of a tactic is the space of the Other. -

GUÍA De Creación De Personaje CTHULHU

Foundation for Archeological Research Guía para nuevos miembros Una guía no-oficial para crear investigadores para el juego de rol “La Llamada de Cthulhu” ” publicado en España por Edge Entertainment bajo licencia de Chaosium. Para ser utilizado principalmente en “Los Misterios de Bloomfield”-“The Bloomfield Mysteries”, una adaptación de “La Sombra de Saros”, campaña escrita por Xabier Ugalde, para su uso en las aulas de Primaria en las áreas de Ciencias Sociales, Lengua Castellana y Lengua Extranjera: Inglés Adaptado para Educación Primaria por: ÓscarRecio Coll [email protected] https://jueducacion.com/ El Copyright de las ilustraciones de La Llamada de Cthulhu y de La Sombra de Saros además de otras presentes en este material así como la propiedad intelectual/comercial/empresarial y derechos de las mismas son exclusiva de sus autores y/o de las compañías y editoriales que sean propietarias o hayan comprado los citados derechos sobre las obras y posean sobre ellas el derecho a que se las elimine de esta publicación de tal manera que sus derechos no queden vulnerados en ninguna forma o modo que pudiera contravenir su autoría para particulares y/o empresas que las hayan utilizado con fines comerciales y/o empresariales. Esta compilación no tiene ningún uso comercial ni ánimo de lucro y está destinada exclusivamente a su utilización dentro del ámbito escolar y su finalidad es completamente didáctica como material de desarrollo y apoyo para la dinamización de contenidos en las diferentes áreas que componen la Educación Primaria. Bienvenidos/as a la F.A.R. (Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas), en este sencillo manual encontrarás las instrucciones para ser parte de nuestra fundación y completar tu registro como miembro. -

New Books Catalogue 2017-18

PHILOSOPHY, PAGE 2 THEOLOGY, BIBLICAL STUDIES& PAGE 29 RELIGIOUS STUDIES PAGE 41 NEW BOOKS CATALOGUE 2017-18 PAGE 50 9 781350 057005 PhilTheoBib_FINAL.indd 1-2 03/08/2017 11:19 TM Instant digital access to more than 6,000 eBooks across the social sciences and humanities, including titles from The Arden Shakespeare, Continuum, Bristol Classical Press, and Berg. Subjects covered include: Anthropology • Biblical Studies • Classical Studies & Archaeology • Education • Film & Media • History • Law • Linguistics • Literary Studies • Philosophy • Religious Studies • Theology CONTENT HIGHLIGHTS FEATURES • 125 Collections, expanded annually by subject discipline • Advanced and full text search across all content. • Archive Collections in key subject areas such as ancient • Filter results by subject, series, or collection history, Christology, continental philosophy, and more • Pagination matches print exactly • Special Collections such as International Critical • Personalization features: save searches, export citations Commentary, Ancient Commentators on Aristotle, and and favorite, download, or print documents Education Around the World series • Footnotes, endnotes, and bibliographic references are hyperlinked To register your interest for a free institutional trial, or for further information email: Americas: [email protected] UK, Europe, Middle East, Africa, Asia: [email protected] Australia and New Zealand: [email protected] www.bloomsburycollections.com Collections_advert_2.indd 1 19/07/2017 08:52 Contents -

![The Regulation of the Subject by the Technology of Time Maxwell Kennel [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8359/the-regulation-of-the-subject-by-the-technology-of-time-maxwell-kennel-1-388359.webp)

The Regulation of the Subject by the Technology of Time Maxwell Kennel [1]

Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 34 (2018) The Regulation of the Subject by the Technology of Time Maxwell Kennel [1] Abstract: Beginning from the entangled categories of the human and the technological, this exploration surveys thinkers who concern themselves with problems of technology and time, seeking to examine how the confluence of technology and time regulate and condition the formation of subjectivity. Drawing on Bernard Stiegler's work in Technics and Time, Augustine's Confessions, and the myth of Prometheus, the following draws out the technological character of time and makes suggestions about how to reconceptualize these different temporalizing technologies after the critique of capitalism. Surely technology, in its ever-changing form and forms, is a pharmakon that has been with us from the start. Regardless of whether we speak of technology or technologies or the broader field of techne (a practice or craft), it remains that the term ‘technology’ refers to something that, like a double-edged sword, helps us and harms us, something that we use and that uses us, and something that is at once politically charged (often subtly oriented toward particular interests and ends with particular benefactors), yet ambivalent, taking different sides at different times (and therefore available for us to use as means for our own ends).[2] Although it is at our disposal and supposedly outside of ourselves, some have argued that technology is not in fact something extra that is added onto our human nature and experience, but instead something inextricably related to both humanity and history, and indeed something that challenges the legitimacy of these categories. -

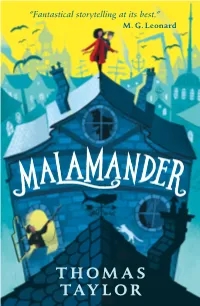

Malamander-Extract.Pdf

“Fantastical storytelling at its best.” M. G. Leonard THOMAS TAYLOR THOMAS TAYLOR This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. All statements, activities, stunts, descriptions, information and material of any other kind contained herein are included for entertainment purposes only and should not be relied on for accuracy or replicated as they may result in injury. First published 2019 by Walker Books Ltd 87 Vauxhall Walk, London SE11 5HJ 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Text and interior illustrations © 2019 Thomas Taylor Cover illustrations © 2019 George Ermos The right of Thomas Taylor to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This book has been typeset in Stempel Schneider Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, taping and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-4063-8628-8 (Trade) ISBN 978-1-4063-9302-6 (Export) ISBN 978-1-4063-9303-3 (Exclusive) www.walker.co.uk Eerie-on-Sea YOU’VE PROBABLY BEEN TO EERIE-ON-SEA, without ever knowing it. When you came, it would have been summer. -

Anthropoetics VIII, 2

Anthropoetics VIII, 2 Anthropoetics VIII, no. 2 Fall 2002 / Winter 2003 ISSN 1083-7264 Table of Contents 1. Chris Fleming and John O'Carroll - Notes on Generative Anthropology: Towards an Ethics of the Hypothesis 2. Thomas Bertonneau - Post-Imperium: The Rhetoric of Liberation and the Return of Sacrifice in the Work of V. S. Naipaul 3. Douglas Collins - The Great Effects of Small Things: Insignificance With Immanence in Critical Theory 4. Raoul Eshelman - Performatism in the Movies (1997-2003) 5. Matthew Schneider - "What matters is the system!" The Beatles, the "Passover Plot," and Conspiratorial Narrativity 6. Benchmarks Return to Anthropoetics home page Eric Gans / [email protected] Last updated: http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0802/ap0802.htm [1/14/2003 11:45:13 PM] Fleming & O'Carroll - Notes on Generative Anthropology: Towards an Ethics of the Hypothesis Anthropoetics 8, no. 2 (Fall 2002 / Winter 2003) Notes on Generative Anthropology: Towards an Ethics of the Hypothesis Chris Fleming and John O'Carroll School of Humanities University of Western Sydney Penrith South DC NSW 1797 Australia [email protected] [email protected] 1. Eric Gans, the Hypothesis, and the Humanities Scholars in the human sciences (the arts, liberal thought, and the verstehen varieties of social sciences) are often called upon to supply new modes of thinking to meet the challenges of a post-Marxist, post-modern, even post-humanist world. A new cartography of methodological expectations and possibilities within the purview of these human sciences would now appear desirable. Never has the world of thought-about-thought been required to perform so much, and only rarely, regrettably, has it offered so little. -

American Gothic: a Creative Exploration

AMERICAN GOTHIC: A CREATIVE EXPLORATION Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English By Aaron Trevor Goode UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio May 2019 AMERICAN GOTHIC: A CREATIVE EXPLORATION Name: Goode, Aaron Trevor APPROVED BY: ___________________________________ Bryan Bardine, Ph.D. Committee Chair Professor ___________________________________ Christopher Burnside, MFA Committee Member Professor ___________________________________ Stephen Wilhoit, PhD. Committee Member Professor ii © Copyright by Aaron Trevor Goode All rights reserved 2019 iii ABSTRACT AMERICAN GOTHIC: A CREATIVE EXPLORATION Name: Goode, Aaron Trevor University of Dayton Advisor: Bryan Bardine This work endeavors to explore the various movements of American Gothic by presenting an original narrative that represents key facets of each movement. Various authors and subgenres are mentioned throughout via text boxes containing annotative notes. These annotations are intended to enhance reader understanding of the American Gothic genre by familiarizing them with the stylistic conventions common to key authors and famous works of the genre. The story itself is broken up into seven sections, each distinct with regard to style and content while maintaining a cohesive narrative with a unified plot. As the readers progress through the plot, they will also progress chronologically through the history of American Gothic. from the earliest work of Charles Brockden Brown up to the Postmodern style of Mark Danielewski. iv Dedicated to My Wife v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my advisor, Dr. Bardine, for his openness to this unconventional project, as well as for the opportunity to discuss metal and attend shows with his students. -

Found Media: Interactivity and Community in Online Horror Media

SUNY College Cortland Digital Commons @ Cortland Master's Theses 4-2021 Found media: interactivity and community in online horror media Jax Mello Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cortland.edu/theses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, Fiction Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Social Media Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Found Media: Interactivity and Community in Online Horror Media by Jax Mello A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Master of Arts in English Department of English, School of Arts and Sciences STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK COLLEGE AT CORTLAND April 2021 Master of Arts Thesis, English Department SUNY Cortland Student Signature: ______________________________________________________ Thesis Title: Found Media: Interactivity and Community in Online Horror Media Thesis Advisor’s Signature: _______________________________________________ MA Coordinator’s Signature: ______________________________________________ Being isolated is a common fear. The fear can take many forms, from the fear of being the last one alive in a horrific situation to being completely deserted by everyone you love. This is a fear that has been showcased many different times in movies, novels, and every other piece of media imaginable. Although not always tied to the horror genre, the fear of being isolated is tightly intertwined with many horror stories. Therefore, it is interesting when a horror production goes out of their way to encourage interactivity within its audience. This goes beyond an artist’s desire for a creation to have a raving fanbase behind it, which is typically generated through external means from the narrative itself. Instead, there is an as-yet-unaccounted-for subgenre of horror that integrates Found Footage techniques with the specific goal of eliciting interactivity within the audience. -

And Concrete Island

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by York St John University Institutional Repository York St John University Beaumont, Alexander (2016) Ballard’s Island(s): White Heat, National Decline and Technology After Technicity Between ‘The Terminal Beach’ and Concrete Island. Literary geographies, 2 (1). pp. 96-113. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/2087/ The version presented here may differ from the published version or version of record. If you intend to cite from the work you are advised to consult the publisher's version: http://literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGeogs/article/view/39 Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] Beaumont: Ballard’s Island(s) 96 Ballard’s Island(s): White Heat, National Decline and Technology After Technicity Between ‘The Terminal Beach’ and Concrete Island Alexander Beaumont York St John University _____________________________________ Abstract: This essay argues that the early fiction of J.G. Ballard represents a complex commentary on the evolution of the UK’s technological imaginary which gives the lie to descriptions of the country as an anti-technological society.