Donald Trump, the Changes: Aanti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

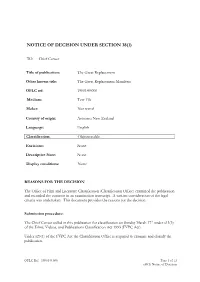

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

Chapter 4 the Right-Wing Media Enablers of Anti-Islam Propaganda

Chapter 4 The right-wing media enablers of anti-Islam propaganda Spreading anti-Muslim hate in America depends on a well-developed right-wing media echo chamber to amplify a few marginal voices. The think tank misinforma- tion experts and grassroots and religious-right organizations profiled in this report boast a symbiotic relationship with a loosely aligned, ideologically-akin group of right-wing blogs, magazines, radio stations, newspapers, and television news shows to spread their anti-Islam messages and myths. The media outlets, in turn, give members of this network the exposure needed to amplify their message, reach larger audiences, drive fundraising numbers, and grow their membership base. Some well-established conservative media outlets are a key part of this echo cham- ber, mixing coverage of alarmist threats posed by the mere existence of Muslims in America with other news stories. Chief among the media partners are the Fox News empire,1 the influential conservative magazine National Review and its website,2 a host of right-wing radio hosts, The Washington Times newspaper and website,3 and the Christian Broadcasting Network and website.4 They tout Frank Gaffney, David Yerushalmi, Daniel Pipes, Robert Spencer, Steven Emerson, and others as experts, and invite supposedly moderate Muslim and Arabs to endorse bigoted views. In so doing, these media organizations amplify harm- ful, anti-Muslim views to wide audiences. (See box on page 86) In this chapter we profile some of the right-wing media enablers, beginning with the websites, then hate radio, then the television outlets. The websites A network of right-wing websites and blogs are frequently the primary movers of anti-Muslim messages and myths. -

Robert Spencer Article

THE SPENCER SPIN “spin” v. Taking informational material, and twisting, slanting, misinterpreting, misquoting, or changing it in an effort to make it support your own personal agenda. See media, propaganda, political campaigns, racists, and Robert Spencer. INTRODUCTION The first things I asked myself in reviewing the mountain of material for this article was what possible conclusions could be reached, and how to organize all this information. Using the standard journalist’s verbiage, the best overarching explanation of such is: WHO: (The target of this article) Robert H. Spencer, aka Robert Bruce Spencer, aka Hugh Fitzgerald, aka Jihad Watch, aka Dhimmi Watch. WHY: Spencer is one of the most prolific writers of anti-Islamic claims, publishing on blogs, online and print journals, writing 6 books, appearing on television on the subject, where he is erroneously proclaimed “a scholar of Islam”, “a scholar of law” and “a scholar of history.” WHAT: What are Spencer’s his exact positions, on what does he support those positions, and what is his motivation for holding those positions? WHEN: Spencer appears to have been engaged in his campaign against Islam since 2002. My research on Spencer covers a period of roughly hours over twelve months. HOW: I utilized the Internet, religious texts, legal texts, theological dissertations, historical analyses; read many hundreds of Spencer’s writings, and engaged in an extended and intense email discussion with Spencer over a period of about 6 months. I maintained an enormous amount of notes and reference material, along with originals of all emails, online articles, references, etc. I then organized the material, found that I had enough to write a book, and went through (as of this writing, which may be before the edition that you are reading), 68 drafts to summarize my findings in a short enough article that you wouldn’t fall asleep reading it. -

Gatestone Institute

GATESTONE INSTITUTE IMPACT: Gatestone has published a steady stream of content aimed at stoking fears of a Muslim takeover of Europe and America. The articles warn that increasing Muslim migration to Europe will lead to the “Islamization” of the continent. Gatestone’s pieces have been cited by far-right politicians to justify their anti- Muslim policies. • Gatestone Institute was founded in 2008 under the name “Hudson New York” by Nina Rosenwald. In 2012, the organization briefly changed its name to “Stonegate Institute.” Later that year, the organization adopted its current name. Gatestone describes itself as an “international policy council and think tank.” The former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and current national security adviser to President Donald Trump, John Bolton, served as the Institute’s chairman since 2013. • Rosenwald is the heiress to the Sears Roebuck fortune. A 2011 report by the Center for American Progress found that since 2001, Rosenwald, through her family foundation, the William Rosenwald Family Fund, donated more than $2.8 million to “organizations that fan the flames of Islamophobia.” The Center for American Progress identified the family fund as one of the the top seven funders of Islamophobia. • A September 2017 article in The Intercept by investigative journalist Lee Fang found that Gatestone published articles “focused on stoking fears about immigrants and Muslims.” In another article from 2018, Fang noted Gatestone was “infamous for its role in publishing ‘fake news’ and spreading hate about Muslims.” Fang also found that Gatestone’s anti-Muslim content had been regularly promoted by politicians, including members and affiliated online groups, of the far-right German party, Alternative for Germany (AfD). -

Une Si Longue Presence: Comment Le Monde Arabe a Perdu Ses Juifs 1947-1967 by Nathan Weinstock, Plon, 2008, 358 Pp

Une si longue presence: comment le monde arabe a perdu ses juifs 1947-1967 by Nathan Weinstock, Plon, 2008, 358 pp. Lyn Julius The picture on the front cover of Nathan Weinstock’s book Une si longue presence shows two barred windows. Through the window on the left, the sultan’s lions peer out. In the adjoining cage, the Jews of Fez. When the photograph was taken in 1912, the Jews were sheltering in the sultan’s menagerie from a murderous riot on the eve of the establishment of the French protectorate of Morocco. The implication is clear: the Jews’ place is with the sultan’s beasts. It was the Jews’ job to feed the lions. In times of trouble, what place of refuge could be more natural than the sultan’s menagerie? The lions have long gone, and so have the Jews. Almost all the Jewish communities of the Middle East and North Africa have been driven to extinction: most went to Israel, where half the Jews or their descendants come from Muslim lands. A lethal cocktail of state-sanctioned persecution and mob violence, modulated to the peaks of Arab-Israeli tension, has caused the Jewish population to dwindle from one million in 1948 to 4,500 in one generation. It was an ethnic cleansing, says Weinstock, not even rivalled by Nazi Germany in 1939. Such a calamity cannot be explained by the Jews’ failure to integrate. They were indigenous, having for the most part settled in the Middle East and North Africa over 2,000 years ago – one thousand years before the advent of Islam. -

Democracy and Dissent: Strauss, Arendt, and Voegelin in America

Denver Law Review Volume 89 Issue 3 Special Issue - Constitutionalism and Article 6 Revolutions December 2020 Democracy and Dissent: Strauss, Arendt, and Voegelin in America Stephen M. Feldman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Stephen M. Feldman, Democracy and Dissent: Strauss, Arendt, and Voegelin in America, 89 Denv. U. L. Rev. 671 (2012). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. DEMOCRACY AND DISSENT: STRAUSS, ARENDT, AND VOEGELIN IN AMERICA STEPHEN M. FELDMANt During the 1930s, American democratic government underwent a paradigmatic transformation.' From the framing through the 1920s, the United States operated as a republican democracy. Citizens and elected officials were supposed to be virtuous: in the political realm, they were to pursue the common good or public welfare rather than their own "par- tial or private interests."2 Intellectually, republican democracy had premodern roots stretching back to antiquity. 3 As such, republican demo- cratic theorists often conceptualized the common good in objectivist terms, as if there existed a distinct good that could be clearly ascer- tained.4 Equally important, for at least a century, republican democracy seemed to fit the agrarian, rural, and relatively homogenous American society. Thomas Jefferson, for one, insisted that the agrarian economy and widespread rural land ownership promoted a virtuous commitment to the common good.5 And given that, in the nation's early decades, an overwhelming number of Americans were Protestants who traced their ancestry to Western or Northern Europe, the people seemed sufficiently homogeneous to join together in the pursuit of the common good.6 Of course, some Americans did not fit the mold. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

Democratic Vanguardism

Democratic Vanguardism Modernity, Intervention, and the making of the Bush Doctrine Michael Harland A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History University of Canterbury 2013 For Francine Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 3 Introduction 4 1. America at the Vanguard: Democracy Promotion and the Bush Doctrine 16 2. Assessing History’s End: Thymos and the Post-Historic Life 37 3. The Exceptional Nation: Power, Principle and American Foreign Policy 55 4. The “Crisis” of Liberal Modernity: Neoconservatism, Relativism and Republican Virtue 84 5. An “Intoxicating Moment:” The Rise of Democratic Globalism 123 6. The Perfect Storm: September 11 and the coming of the Bush Doctrine 159 Conclusion 199 Bibliography 221 1 Acknowledgements Over the three years I spent researching and writing this thesis, I have received valuable advice and support from a number of individuals and organisations. My supervisors, Peter Field and Jeremy Moses, were exemplary. As my senior supervisor, Peter provided a model of a consummate historian – lively, probing, and passionate about the past. His detailed reading of my work helped to hone the thesis significantly. Peter also allowed me to use his office while he was on sabbatical in 2009. With a library of over six hundred books, the space proved of great use to an aspiring scholar. Jeremy Moses, meanwhile, served as the co-supervisor for this thesis. His research on the connections between liberal internationalist theory and armed intervention provided much stimulus for this study. Our discussions on the present trajectory of American foreign policy reminded me of the continuing pertinence of my dissertation topic. -

Far-Right Anthology

COUNTERINGDEFENDING EUROPE: “GLOBAL BRITAIN” ANDTHE THEFAR FUTURE RIGHT: OFAN EUROPEAN ANTHOLOGY GEOPOLITICSEDITED BY DR RAKIB EHSAN AND DR PAUL STOTT BY JAMES ROGERS DEMOCRACY | FREEDOM | HUMAN RIGHTS ReportApril No 2020. 2018/1 Published in 2020 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society Millbank Tower 21-24 Millbank London SW1P 4QP Registered charity no. 1140489 Tel: +44 (0)20 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2020. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its Trustees. Title: “COUNTERING THE FAR RIGHT: AN ANTHOLOGY” Edited by Dr Rakib Ehsan and Dr Paul Stott Front Cover: Edinburgh, Scotland, 23rd March 2019. Demonstration by the Scottish Defence League (SDL), with supporters of National Front and white pride, and a counter demonstration by Unite Against Facism demonstrators, outside the Scottish Parliament, in Edinburgh. The Scottish Defence League claim their protest was against the sexual abuse of minors, but the opposition claim the rally masks the SDL’s racist beliefs. Credit: Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert/Alamy Live News. COUNTERINGDEFENDING EUROPE: “GLOBAL BRITAIN” ANDTHE THEFAR FUTURE RIGHT: OFAN EUROPEAN ANTHOLOGY GEOPOLITICSEDITED BY DR RAKIB EHSAN AND DR PAUL STOTT BY JAMES ROGERS DEMOCRACY | FREEDOM | HUMAN RIGHTS ReportApril No 2020. 2018/1 Countering the Far Right: An Anthology About the Editors Dr Paul Stott joined the Henry Jackson Society’s Centre on Radicalisation and Terrorism as a Research Fellow in January 2019. An experienced academic, he received an MSc in Terrorism Studies (Distinction) from the University of East London in 2007, and his PhD in 2015 from the University of East Anglia for the research “British Jihadism: The Detail and the Denial”. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Register of Lords' Interests

REGISTER OF LORDS’ INTERESTS _________________ The following Members of the House of Lords have registered relevant interests under the code of conduct: ABERDARE, LORD Category 8: Gifts, benefits and hospitality Attended with wife, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 25 July 2014, as guests of Welsh Government Category 10: Non-financial interests (a) Director, F.C.M. Limited (recording rights) Category 10: Non-financial interests (c) Trustee, Berlioz Society Trustee, St John Cymru-Wales Trustee, National Library of Wales Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Trustee, West Wycombe Charitable Trust ADAMS OF CRAIGIELEA, BARONESS Nil No registrable interests ADDINGTON, LORD Category 1: Directorships Chairman, Microlink PC (UK) Ltd (computing and software) Category 7: Overseas visits Visit to Dublin, 6-7 May 2015, to talk on UK Election at seminar organised by Goodbody and the British Irish Chamber of Commerce who paid for airfares, accommodation and hospitality Category 10: Non-financial interests (d) Vice President, British Dyslexia Association Category 10: Non-financial interests (e) Vice President, UK Sports Association Vice President, Lakenham Hewitt Rugby Club ADEBOWALE, LORD Category 1: Directorships Director, Leadership in Mind Ltd (business activities; certain income from services provided personally by the Member is or will be paid to this company or to TomahawkPro Ltd; see category 4(a)) Non-executive Director, Three Sixty Action Ltd (holding company; community development, media and IT) (see category 4(a)) Non-executive Director, TomahawkPro Ltd (a subsidiary of Three Sixty Action Ltd; collaborative software & IT innovation; no income from this post is received at present; certain income from services provided personally by the Member is or will be paid to this company or to Leadership in Mind Ltd; see category 4(a)) Category 2: Remunerated employment, office, profession etc.