Why We Need to Revisit the Word of God – Preliminaries (Continued)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kriya-Yoga" in the Youpi-Sutra

ON THE "KRIYA-YOGA" IN THE YOUPI-SUTRA By Shingen TAKAGI The Yogasutra (YS.) defines that yoga is suppression of the activity of mind in its beginning. The Yogabhasya (YBh.) by Vyasa, the oldest (1) commentary on this sutra says "yoga is concentration (samadhi)". Now- here in the sutra itself yoga is not used as a synonym of samadhi. On the other hand, Nyayasutra (NS.) 4, 2, 38 says of "the practice of a spe- cial kind of concentration" in connection with realizing the cognition of truth, and also NS. 4, 2, 42 says that the practice of yoga should be done in a quiet places such as forest, a natural cave, or river side. According NS. 4, 2, 46, the atman can be purified through abstention (yama), obser- vance (niyama), through yoga and the means of internal exercise. It can be surmised that the author of NS. also used the two terms samadhi and yoga as synonyms, since it speaks of a special kind of concentration on one hand, and practice of yoga on the other. In the Nyayabhasya (NBh. ed. NS. 4, 2, 46), the author says that the method of interior exercise should be understood by the Yogasastra, enumerating austerity (tapas), regulation of breath (pranayama), withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara), contem- plation (dhyana) and fixed-attention (dharana). He gives the practice of yoga (yogacara) as another method. It seems, through NS. 4, 2, 46 as mentioned above, that Vatsyayana regarded yama, niyama, tapas, prana- yama, pratyahara, dhyana, dharana and yogacara as the eight aids to the yoga. -

Universal Mythology: Stories

Universal Mythology: Stories That Circle The World Lydia L. This installation is about mythology and the commonalities that occur between cultures across the world. According to folklorist Alan Dundes, myths are sacred narratives that explain the evolution of the world and humanity. He defines the sacred narratives as “a story that serves to define the fundamental worldview of a culture by explaining aspects of the natural world, and delineating the psychological and social practices and ideals of a society.” Stories explain how and why the world works and I want to understand the connections in these distant mythologies by exploring their existence and theories that surround them. This painting illustrates the connection between separate cultures through their polytheistic mythologies. It features twelve deities, each from a different mythology/religion. By including these gods, I have allowed for a diversified group of cultures while highlighting characters whose traits consistently appear in many mythologies. It has the Celtic supreme god, Dagda; the Norse trickster god, Loki; the Japanese moon god, Tsukuyomi; the Aztec sun god, Huitzilopochtli; the Incan nature goddess, Pachamama; the Egyptian water goddess, Tefnut; the Polynesian fire goddess, Mahuika; the Inuit hunting goddess, Arnakuagsak; the Greek fate goddesses, the Moirai: Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos; the Yoruba love goddess, Oshun; the Chinese war god, Chiyou; and the Hindu death god, Yama. The painting was made with acrylic paint on mirror. Connection is an important element in my art, and I incorporate this by using the mirror to bring the audience into the piece, allowing them to see their reflection within the parting of the clouds, whilst viewing the piece. -

Yudhishthira's Wisdom Is an Ancient Story

Yudhishthira's wisdom is an ancient story. Which is a part of Mahabharata, Indian greatest epic? Or it simply says a journey of five brothers in the jungle. Four levels parts for this text Literal comprehension, interpretation, critical thinking/ analysis, and assimilation are: Yudhishthira's wisdom Source: Mahabharata BBA|BBA-BI|BBA-TT|BHCM|BHM|BCIS|BHM Literal comprehension of this story The story ' Yudhishthira's wisdom ' has been taken from the greatest epic 'Mahabharata'. Once upon a time five Pandavas brother's were wondering in a forest to hunt a deer. But the deer in their sight disappeared suddenly. In the min time, they felt tiredness grew thirsty & they were unable to move ahead. They set under a tree & Yudhisthira's sent his eldest brother Sahadeva. To search for water but he didn't come for a long time. He sent his entire brother's one after the other gradually. However, none of them returned for a long time. Therefore, ultimately Yudhisthira's himself set out in search of his bother's following their footprints. After a short walk, he notices a beautiful pool. On its bank, his four brother's were lying either unconsciousness or death. Although viewing the events he was in stream distress & sorrow. Then he bent to drink water from the pool but an unknown voice warned him. Not to drink water from the pool before answering his questions. After listening carefully Yudhisthira's tactfully answered all questions of Yama(the god of justice & death). His four brothers were prostrate on the ground due to their disobedience to the voice of Yama. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

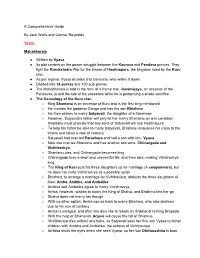

A Comprehensive Guide by Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts

A Comprehensive Guide By Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts: Mahabharata ● Written by Vyasa ● Its plot centers on the power struggle between the Kaurava and Pandava princes. They fight the Kurukshetra War for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. ● As per legend, Vyasa dictates it to Ganesha, who writes it down ● Divided into 18 parvas and 100 subparvas ● The Mahabharata is told in the form of a frame tale. Janamejaya, an ancestor of the Pandavas, is told the tale of his ancestors while he is performing a snake sacrifice ● The Genealogy of the Kuru clan ○ King Shantanu is an ancestor of Kuru and is the first king mentioned ○ He marries the goddess Ganga and has the son Bhishma ○ He then wishes to marry Satyavati, the daughter of a fisherman ○ However, Satyavati’s father will only let her marry Shantanu on one condition: Shantanu must promise that any sons of Satyavati will rule Hastinapura ○ To help his father be able to marry Satyavati, Bhishma renounces his claim to the throne and takes a vow of celibacy ○ Satyavati had married Parashara and had a son with him, Vyasa ○ Now she marries Shantanu and has another two sons, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya ○ Shantanu dies, and Chitrangada becomes king ○ Chitrangada lives a short and uneventful life, and then dies, making Vichitravirya king ○ The King of Kasi puts his three daughters up for marriage (A swayamvara), but he does not invite Vichitravirya as a possible suitor ○ Bhishma, to arrange a marriage for Vichitravirya, abducts the three daughters of Kasi: Amba, -

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic Form)

Vishvarupadarsana Yoga (Vision of the Divine Cosmic form) 55 Verses Index S. No. Title Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Verse 1 5 3. Verse 2 15 4. Verse 3 19 5. Verse 4 22 6. Verse 6 28 7. Verse 7 31 8. Verse 8 33 9. Verse 9 34 10. Verse 10 36 11. Verse 11 40 12. Verse 12 42 13. Verse 13 43 14. Verse 14 45 15. Verse 15 47 16. Verse 16 50 17. Verse 17 53 18. Verse 18 58 19. Verse 19 68 S. No. Title Page No. 20. Verse 20 72 21. Verse 21 79 22. Verse 22 81 23. Verse 23 84 24. Verse 24 87 25. Verse 25 89 26. Verse 26 93 27. Verse 27 95 28. Verse 28 & 29 97 29. Verse 30 102 30. Verse 31 106 31. Verse 32 112 32. Verse 33 116 33. Verse 34 120 34. Verse 35 125 35. Verse 36 132 36. Verse 37 139 37. Verse 38 147 38. Verse 39 154 39. Verse 40 157 S. No. Title Page No. 40. Verse 41 161 41. Verse 42 168 42. Verse 43 175 43. Verse 44 184 44. Verse 45 187 45. Verse 46 190 46. Verse 47 192 47. Verse 48 196 48. Verse 49 200 49. Verse 50 204 50. Verse 51 206 51. Verse 52 208 52. Verse 53 210 53. Verse 54 212 54. Verse 55 216 CHAPTER - 11 Introduction : - All Vibhutis in form of Manifestations / Glories in world enumerated in Chapter 10. Previous Description : - Each object in creation taken up and Bagawan said, I am essence of that object means, Bagawan is in each of them… Bagawan is in everything. -

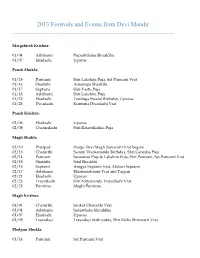

2013 Festivals and Events from Devi Mandir

2013 Festivals and Events from Devi Mandir Margshirsh Krishna: 01/04 Ashthami Pupashthaka Shraddha 01/07 Ekadashi Upavas Paush Shukla: 01/15 Pancami Shri Lakshmi Puja, Sat Pancami Vrat 01/16 Shashthi Annarupa Shashthi 01/17 Saptami Shri Vastu Puja 01/18 Ashthami Shri Lakshmi Puja 01/22 Ekadashi Trailinga Swami Birthday, Upavas 01/23 Dwadashi Kurmma Dwadashi Vrat Paush Krishna: 02/06 Ekadashi Upavas 02/08 Chaturdashi Shri Ratantikalika Puja Magh Shukla: 02/10 Pratipad Durga Devi Magh Navaratri Vrat begins 02/13 Chaturthi Swami Vivekananda Birthday, Shri Ganesha Puja 02/14 Pancami Saraswati Puja & Lakshmi Puja, Shri Pancami, Sat Pancami Vrat 02/15 Shashthi Sital Shashthi 02/16 Saptami Arogya Saptami Vrat, Makari Saptami 02/17 Ashthami Bhishmashtami Vrat and Tarpan 02/21 Ekadashi Upavas 02/23 Trayodashi Shri Nityananda Trayodashi Vrat 02/25 Purnima Maghi Purnima Magh Krishna: 03/01 Chaturthi Sankat Chaturthi Vrat 03/04 Ashthami Sakasthaka Shraddha 03/07 Ekadashi Upavas 03/09 Trayodasi Trayodasi nishi yukta, Shri Maha Shivaratri Vrat Phalgun Shukla: 03/16 Pancami Sat Pancami Vrat 03/17 Shashthi Gorupini Shashthi 03/22 Ekadashi Shri Ramakrishna’s Birthday 03/26 Purnima Shri Krishna Dol Yatra, Holi, Gauranga Mahaprabhu Avirbhav Phalgun Krishna: 03/31 Pancami Shri Krishna Pancama Dol Yatra 04/01 Shashthi Skanda Shashthi 04/03 Ashthami Shri Sitalashtami 04/05 Ekadashi Upavas 04/07 Trayodashi Madhu Krishna Trayodashi Caitra Shukla: 04/10 Pratipad Vasanti Durga Devi Navaratri Vrat 04/15 Pancami Sat Pancami Vrat 04/16 Shashthi Shri Vasanti Durga -

The Mahabharata

VivekaVani - Voice of Vivekananda THE MAHABHARATA (Delivered by Swami Vivekananda at the Shakespeare Club, Pasadena, California, February 1, 1900) The other epic about which I am going to speak to you this evening, is called the Mahâbhârata. It contains the story of a race descended from King Bharata, who was the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntalâ. Mahâ means great, and Bhârata means the descendants of Bharata, from whom India has derived its name, Bhârata. Mahabharata means Great India, or the story of the great descendants of Bharata. The scene of this epic is the ancient kingdom of the Kurus, and the story is based on the great war which took place between the Kurus and the Panchâlas. So the region of the quarrel is not very big. This epic is the most popular one in India; and it exercises the same authority in India as Homer's poems did over the Greeks. As ages went on, more and more matter was added to it, until it has become a huge book of about a hundred thousand couplets. All sorts of tales, legends and myths, philosophical treatises, scraps of history, and various discussions have been added to it from time to time, until it is a vast, gigantic mass of literature; and through it all runs the old, original story. The central story of the Mahabharata is of a war between two families of cousins, one family, called the Kauravas, the other the Pândavas — for the empire of India. The Aryans came into India in small companies. Gradually, these tribes began to extend, until, at last, they became the undisputed rulers of India. -

Elements of Hinduism in Chandra's Red Earth and Pouring Rain

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 14 (2012) Issue 2 Article 6 Elements of Hinduism in Chandra’s Red Earth and Pouring Rain Corinne M. Ehrfurth Rochester Mayo High School Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ehrfurth, Corinne M "Elements of Hinduism in Chandra’s Red Earth and Pouring Rain." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 14.2 (2012): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1844> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Bhagavad Gita Free

öËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | é∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú-æËíŸæ “ Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ úŸ≤¤™‰ ™ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | éÂ∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ 韺Π∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº ∫Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿ §-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | -⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿ËßThe‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%Bhagavad‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å Gita || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸ {Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤ æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’ ≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘ ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥The˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸº OriginalÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅSanskrit é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰ —ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ “‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºand Î ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸº Å Ç—™‹ ™—ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿ Ÿ ∏“‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§- An English Translation ≤Ÿ¨Ÿæ -

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups on Kurukshetra

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups On Kurukshetra 1. On the fifteenth day of the Kurukshetra War, Krishna came up with a plan to kill this character. The previous night, this character retracted his Brahmastra [Bruh-mah-struh] when he was reprimanded for using a divine weapon on ordinary soldiers. After Bharadwaja ejaculated into a vessel when he saw a bathing Apsara, this character was born from the preserved semen. Because he promised that Arjuna would be the greatest archer in the world, this character demanded that (*) Ekalavya give him his right thumb. This character lays down his arms when Yudhishtira [Yoo-dhish-ti-ruh] lied to him that his son is dead, when in fact it was an elephant named Ashwatthama that was dead.. For 10 points, name this character who taught the Pandavas and Kauravas military arts. ANSWER: Dronacharya 2. On the second day of the Kurukshetra war, this character rescues Dhristadyumna [Dhrish-ta-dyoom-nuh] from Drona. After that, the forces of Kalinga attack this character, and they are almost all killed by this character, before Bhishma [Bhee-shmuh] rallies them. This character assumes the identity Vallabha when working as a cook in the Matsya kingdom during his 13th year of exile. During that year, this character ground the general (*) Kichaka’s body into a ball of flesh as revenge for him assaulting Draupadi. When they were kids, Arjuna was inspired to practice archery at night after seeing his brother, this character, eating in the dark. For 10 points, name the second-oldest Pandava. ANSWER: Bhima [Accept Vallabha before mention] 3. -

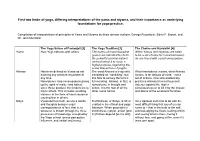

First Two Limbs of Yoga, Differing Interpretations of the Yama and Niyama, and Their Importance As Underlying Foundations for Yoga Practice

First two limbs of yoga, differing interpretations of the yama and niyama, and their importance as underlying foundations for yoga practice. Compilation of interpretations of principles of Yama and Niyama by three renown authors: George Feuerstein, Edvin F. Bryant, and Dr. Jonn Mumford. The Yoga Sutras of Paatanjali [3] The Yoga Tradition [1] The Chakra and Kundalini [4] Yama How Yogi interacts with others The norms of moral discipline When Yamas and Niyamas are taken (yama) are intended to check to be a set of rules for moral behaviour, the powerful survival instinct we are faced with a profound problem. and rechannel it to serve a higher purpose, regulating the social interactions of yogins. Ahimsa Has been defined by Vyasa as not The word Ahimsa is frequently What nonviolence means, what Ahimsa harming any creature anywhere at translated an “nonkilling”, but means, is an attitude of mind – not a any time. this fails to convey the term’s set of actions. One who esoterically Nonviolence also encompasses giving full meaning. Ahimsa, in fact, is practices Ahimsa tries not to permit up the spirit of malice and hatred, nonviolence in thought and violence against the higher since these produce the tendencies to action. It is the root of all the consciousness or to kill it by the misuse injure others. This includes avoiding other moral norms. and abuse of the emotional faculties. violence in the form of harsh words or causing fear in others. Satya Vyasa defines truth, as one’s words Truthfulness, or Satya, is often Inner spiritual truth has to do with the and thoughts being in exact exalted in the ethical and yogic most difficult thing that any of us can correspondence to fact, that is, to literature.