Grampian Hospitals Art Trust (GHAT) Artroom Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contract Between Scottish Ministers

CONTRACT BETWEEN SCOTTISH MINISTERS AND GEOAMEY PECS LTD FOR THE SCOTTISH COURT CUSTODY AND PRISONER ESCORT SERVICE (SCCPES) REFERENCE: 01500 MARCH 2018 Official No part of this document may be disclosed orally or in writing, including by reproduction, to any third party without the prior written consent of SPS. This document, its associated appendices and any attachments remain the property of SPS and will be returned upon request. 1 | P a g e 01500 Scottish Court Custody and Prisoner Escort Service (SCCPES) FORM OF CONTRACT CONTRACT No. 01500 This Contract is entered in to between: The Scottish Ministers, referred to in the Scotland Act 1998, represented by the Scottish Prison Service at the: Scottish Prison Service Calton House 5 Redheughs Rigg Edinburgh EH12 9HW (hereinafter called the “Purchaser”) OF THE FIRST PART And GEOAmey PECS Ltd (07556404) The Sherard Building, Edmund Halley Road Oxford OX4 4DQ (hereinafter called the “Service Provider”) OF THE SECOND PART The Purchaser hereby appoints the Service Provider and the Service Provider hereby agrees to provide for the Purchaser, the Services (as hereinafter defined) on the Conditions of Contract set out in this Contract. The Purchaser agrees to pay to the Service Provider the relevant sums specified in Schedule C and due in terms of the Contract, in consideration of the due and proper performance by the Service Provider of its obligations under the Contract. The Service Provider agrees to look only to the Purchaser for the due performance of the Contract and the Purchaser will be entitled to enforce this Contract on behalf of the Scottish Ministers. -

Health and Social Care Locality Plan Garioch 2018 – 2021 CONTENTS Foreword 3

Aberdeenshire Health & Social Care Partnership Health and Social Care Locality Plan Garioch 2018 – 2021 CONTENTS Foreword 3 1. Introduction 4 1.1 What is a Locality? 4 1.2 What is the Locality Plan? 5 1.3 Who is the Locality Plan for? 5 1.4 What is Included in the Locality Plan? 5 1.5 The Benefits of Locality Planning 6 1.6 The Wider Picture 6 1.7 What are we hoping to Achieve? 8 1.8 What are the Main Challenges? 8 1.9 Locality Planning Group 8 1.10 The Relationship with Community Planning 9 1.11 Local Engagement 10 2. About the Locality 11 2.1 Our Locality - Garioch 11 2.2 Geography 12 2.3 Population 12 2.4 Snapshot of the Population in Garioch 13 2.5 Asset Based Approach 14 2.6 Useful Information 15 3. People and Finances 21 3.1 Health and Social Care Teams 21 3.2 Finance 22 4. What are the People in the Locality Telling Us? 23 4.1 The Main Messages from Local Engagement and Consultation 23 5. Where are we Now 24 5.1 What is Working Well? 24 6. What Do We Need to Do? 31 6.1 Our Local Priorities 31 7. Action Plan 32 8. How will We Know We are Getting There? 35 8.1 Measuring Performance 35 9. Our Next Steps 36 Appendix I 37 Foreword Building on a person’s abilities, we will deliver high quality person centred care to enhance their independence and wellbeing in their own communities. -

Mental Health Bed Census

Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Data Collection Documentation Document Type: Guidance Notes Collections: 1. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census: One Day Audit 2. Mental Health and Learning Disability Patients: Out of Scotland and Out of NHS Placements SG deadline: 30th November 2014 Coverage: Census date: Midnight, 29th Oct 2014 Page 1 – 10 Nov 2014 Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Document Details Issue History Version Status Authors Issue Date Issued To Comments / changes 1.0 Draft Moira Connolly, NHS Boards Beth Hamilton, Claire Gordon, Ellen Lynch 1.14 Draft Beth Hamilton, Ellen Lynch, John Mitchell, Moira Connolly, Claire Gordon, 2.0 Final Beth Hamilton, 19th Sept 2014 NHS Boards, Ellen Lynch, Scottish John Mitchell, Government Moira Connolly, website Claire Gordon, 2.1 Final Ellen Lynch 9th Oct 2014 NHS Boards, Further clarification included for the following data items:: Scottish Government Patient names (applicable for both censuses) website ProcXed.Net will convert to BLOCK CAPITALS, NHS Boards do not have to do this in advance. Other diagnosis (applicable for both censuses) If free text is being used then separate each health condition with a comma. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census o Data item: Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis on admission Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option. o Data item: Last known Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option. -

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST Old Age Psychiatry (sub-specialty: Liaison Psychiatry) VACANCY Consultant in Old Age Psychiatry (sub-specialty: Liaison Psychiatry) Royal Cornhill Hospital, Aberdeen 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent This post is based at Royal Cornhill Hospital, Aberdeen and applications will be welcomed from people wishing to work full-time or part-time and from established Consultants who are considering a new work commitment. The Old Age Liaison Psychiatry Team provides clinical and educational support to both Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and Woodend Hospital and is seen nationally as an exemplar in service delivery. The team benefits from close working relationships with the 7 General Practices aligned Older Adult Community Mental Health Teams in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire and senior colleagues in the Department of Geriatric Medicine. The appointees are likely to be involved in undergraduate and post graduate teaching and will be registered with the continuing professional development programme of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. They will also contribute to audit, appraisal, governance and participate in annual job planning. There are excellent opportunities for research. Applicants must have full GMC registration, a licence to practise and be eligible for inclusion in the GMC Specialist Register. Those trained in the UK should have evidence of higher specialist training leading to a CCT in Old Age Psychiatry or eligibility for specialist registration (CESR) or be within -

NHS Grampian Consultant Anaesthetist (Interest in General Anaesthesia)

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT ANAESTHETIST (Interest in General Anaesthesia) Aberdeen Royal Infirmary VACANCY Consultant Anaesthetist (Interest in General Anaesthesia) Aberdeen Royal Infirmary 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent NHS Grampian Facilities NHS Grampian’s Acute Sector comprises, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI), Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital (RACH), Aberdeen Maternity Hospital (AMH), Woodend Hospital, Cornhill Hospital, and Roxburgh House, all in Aberdeen and Dr Gray’s Hospital, Elgin. Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI) The ARI is the principal adult acute teaching hospital for the Grampian area. It has a complement of approximately 800 beds and houses all major surgical and medical specialties. Most surgical specialties along with the main theatre suite, surgical HDU, and ICU are located within the pink zone of the ARI. The new Emergency Care Centre (see below) is part of ARI and is located centrally within the site. Emergency Care Centre (ECC) The ECC building was opened in December 2012 and houses the Emergency Department (ED), Acute Medical Initial Assessment (AMIA) unit, primary care out-of- hours service (GMED), NHS24, and most medical specialties of the Foresterhill site. The medical HDU (10 beds), Coronary Care Unit, and the GI bleeding unit are also located in the same building. Intensive Care Medicine and Surgical HDU The adult Intensive Care Unit has 16 beds and caters for approximately 700 admissions a year of which, less than 10 per cent are elective and 14 per cent are transfers from other hospitals. The new 18 bedded surgical HDU together with ICU and medical HDU have recently merged under one critical care directorate. -

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST General Adult Psychiatry VACANCY Consultant in General Adult Psychiatry Peterhead, Aberdeenshire 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent Applicants must have full GMC registration, a licence to practise and be eligible for inclusion in the GMC Specialist Register. Those trained in the UK should have evidence of higher specialist training leading to a CCT in General Adult Psychiatry or eligibility for specialist registration (CESR) or be within 6 months of confirmed entry from the date of interview. For further information or to apply for this exciting role, please contact the NHS Scotland International Recruitment Service: Telephone: +44141 278 2712 Email: [email protected] Web: www.international.scot.nhs.uk GLOSSARY AHP Allied Health Profession BPSD Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia CAMHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service CAPA Choice and Partnership Approach CBT Cognitive Behavioural Therapy CCT Certificate of Completion of Training CESR Certificate of Eligibility for Specialist Registration CPD Continuing Professional Development CPN Community Psychiatric Nurse DCC Direct Clinical Care EEA European Economic Area FBT Family Based Treatment GIRFEC Getting it Right for Every Child GMC General Medical Council HR Human Resources HSCP Health and Social Care Partnership IP Inpatient(s) IPCU Intensive Psychiatric Care Unit LD Learning Disabilities MRCPsych Member of the Royal College of Psychiatry NHS National Health Service OOH Out of Hours OP Outpatient(s) PA Programmed Activity PVG Protection of Vulnerable Groups RMN Registered Mental Nurse SCA Scottish Centre for Autism SPA Supporting Professional Activity UK United Kingdom WTE Whole Time Equivalent JOB DESCRIPTION NHS Grampian Consultant Psychiatrist General Adult Psychiatry General information The Mental Health Services Clinical Management Board of NHS Grampian is responsible for the provision of psychiatric services to Aberdeen City, Aberdeenshire, Moray and to Orkney. -

Employment Tribunals (Scotland)

EMPLOYMENT TRIBUNALS (SCOTLAND) Case No: 4104571/18 Held in Aberdeen on 6, 7 and 8 August 2019 Employment Judge Mr N M Hosie Tribunal Member Mr A W Bruce Tribunal Member Ms N Mandel Ms J Ganecka Claimant Represented by Ms L Campbell, Solicitor Grampian Health Board Respondent Represented by Mr A Watson, Solicitor JUDGMENT OF THE EMPLOYMENT TRIBUNAL The unanimous Judgment of the Tribunal is that the claim is dismissed. ETZ4(WR) 4104571/18 Page 2 REASONS Introduction 1. Ms Ganecka brought a claim of direct discrimination in terms of s.13 of the Equality Act 2010 (“the 2010 Act”). She claimed that she was discriminated against because of the protected characteristic of “race” which, in terms of s.9 of the 2010 Act includes “nationality”. She is of Latvian nationality. In short, she complained that, as a so-called, “Bank worker”, she was discriminated against, because of her nationality, when it came to a fair allocation of work and not being offered a permanent contract. Her claim was denied in its entirety by the respondent. The Evidence 2. We heard evidence first from the claimant, Ms Ganecka. 3. We then heard evidence on behalf of the respondent from:- • Jane Lloyd, Assistant HR Manager • Anne Morrison, Assistant Support Services Manager • Shona Strachan, Domestic Supervisor 4. A joint bundle of documentary productions was lodged (“P”), along with a “Statement of Agreed Facts”. The Facts 5. Having heard the evidence and considered the documentary productions, the Tribunal was able to make the following material findings in fact. The claimant began working for the respondent as a Bank worker, domestic assistant, on 13 October 2014. -

Cabinet Secretary for Health and Wellbeing.Dot

Scottish Government Draft Budget 2013-14 Thank you for letter of 2 November 2012 which included a request for further information, helpfully notified to us earlier in the week by your Committee Clerks, together with a range of additional questions of which there was not sufficient time to ask during the meeting on 30 October 2012. I have provided a detailed response to your request for additional information which is included within two annexes as follows:- Annex A: reply to the questions contained within your letter of 2 November 2012 advised previously by Committee Clerks on 31 October 2012; and Annex B: reply to the further questions suggested by members that are annexed in your letter of 2 November 2012 You will appreciate that this information has been drawn together at short notice so if there is anything more you need please do let me know. My officials and I are keen to support the Health and Sport Committee in providing the detailed information it requires in supporting the Scottish Parliament‟s essential scrutiny of the Government‟s Draft Budget plans for 2013-14. ALEX NEIL 1 ANNEX A i. Information on filling of nursing vacancies Statistics The last published figures reported on vacancies within NHS Scotland as at 30th June 2012 and formed part of ISD Workforce statistics released on 30th August. The statistics recorded 984 (wte) vacancies, against a total Nursing & Midwifery workforce of 56,183.7 (wte), representing 1.75% of the total. In relation to the 984 vacancies, 72.4% had been vacant for less then 3 months. -

MASTER) Hospital List (Updated October 2015

HEI (MASTER) Hospital List (updated October 2015) NHS Board Hospital ISD Staffed beds Speciality / Type classification Ayrshire & Arran A&A University Hospital Ayr A2 343 Acute (general with some teaching) University Hospital Crosshouse A2 666 Acute (general with some teaching) Arran War Memorial Hospital A3 19 Acute (mixed speciality) (9) 3 acute Biggart Hospital, Prestwick B6 121 Long stay geriatric & acute 6 community Kirklandside Hospital, Kilmarnock B7 36 Small, long stay geriatric Ayrshire Central Hospital B8 142 Long stay geriatric & acute Davidson Cottage J26 26 Community East Ayrshire Community Hospital, Cumnock J26 57 Community Girvan Community Hospital J26 20 Community Lady Margaret Hospital, Millport J26 9 Community Borders Borders Borders General Hospital A2 265 Acute (general, with some teaching) (5) Hay Lodge Hospital, Peebles J26 23 Community 1 acute Hawick Community Hospital J26 22 Community 4 community Kelso Community Hospital J26 23 Community Knoll Hospital, Duns J26 23 Community Dumfries & Galloway D&G Dumfries & Galloway Royal Infirmary A2 367 Acute (general, with some teaching) Galloway Community Hospital A3 48 Acute (mixed speciality) (10) 2 acute Annan Hospital B7 18 Small, long stay geriatric / rehab 8 community Thornhill Hospital B7 13 Small, long stay geriatric / rehab Thomas Hope Hospital, Langholm B7 10 Small, long stay geriatric / rehab Lochmaben Hospital, Lockerbie B9 17 Long stay geriatric / rehab / psychiatry Castle Douglas Hospital J26 19 Community Kirkcudbright Cottage Hospital J26 9 Community Moffat Hospital J26 12 Community Newton Stewart Hospital J26 19 Community 1 HEI (MASTER) Hospital List (updated October 2015) Fife Fife Victoria Hospital, Kirkcaldy A2 621 Acute (general with some teaching) (7) Queen Margaret Hospital, Dunfermline A3 196 Acute (mixed speciality) 2 acute 5 community Cameron Hospital, Leven B7 95 Small, long stay geriatric Adamson Hospital, Cupar J26 19 Community Glenrothes Hospital J26 74 Community Randolph Wemyss Memorial Hospital J26 16 Community St. -

Scottish ECT Accreditation Network Annual Report 2012

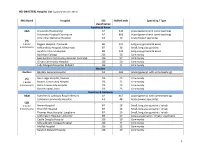

National Services Scotland Scottish ECT Accreditation Network Annual Report 2012 A summary of ECT in Scotland for 2011 SD SC TLAND Scottish ECT Accreditation Network Annual Report 2012; A summary of ECT in Scotland for 2011 © NHS National Services Scotland/Crown Copyright 2012 First published October 2009 Brief extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided the source is fully acknowledged. Proposals for reproduction of large extracts should be addressed to: ISD Scotland Publications Information Services Division NHS National Services Scotland Gyle Square 1 South Gyle Crescent Edinburgh EH12 9EB Tel: +44 (0)131-275-6233 Email: [email protected] Designed and typeset by: ISD Scotland Publications Translation Service If you would like this leaflet in a different language, large print or Braille (English only), or would like information on how it can be translated into your community language, please phone 0131 275 6665. Scottish ECT Accreditation Network Annual Report 2012; A summary of ECT in Scotland for 2011 Summary Hospital Activity Table 20111 Median Median Treatments Stimulations Hospital Patients Episodes Treatments Stimulations per Episode per Episode Ailsa & Crosshouse 35 48 445 478 10.5 11.0 Argyll & Bute * * 27 29 6.0 7.0 Carseview 17 20 195 216 10.0 10.5 Dunnikier * * 68 82 9.0 10.0 Forth Valley Royal2 * * 39 45 4.0 5.0 Hairmyres3 13 15 111 136 8.0 9.0 Huntlyburn, Borders General * 12 144 164 10.5 12.0 Inverclyde 13 13 118 126 8.0 9.0 Leverndale4 25 32 257 289 8.5 10.0 Midpark Hospital5 17 20 151 193 7.0 8.5 Murray Royal 13 14 107 122 7.5 8.5 New Craigs * * 79 90 12.0 12.0 Queen Margaret6 14 17 189 215 10.0 10.0 Royal Cornhill 63 77 556 798 6.0 9.0 Royal Edinburgh7 50 64 773 938 8.0 11.5 St John’s 20 24 197 228 8.0 8.5 Stobhill8 36 41 298 349 7.0 8.0 Susan Carnegie9 * * 62 75 7.0 9.5 Wishaw10 17 19 151 182 7.0 10.0 Total 370 451 3,967 4,755 8.0 9.5 Notes: * Indicates values that have been suppressed because of the potential risk of disclosure. -

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST General Adult Psychiatry VACANCY Consultant in General Adult Psychiatry Jura, Aberdeenshire 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent Applicants must have full GMC registration, a licence to practise and be eligible for inclusion in the GMC Specialist Register. Those trained in the UK should have evidence of higher specialist training leading to a CCT in General Adult Psychiatry or eligibility for specialist registration (CESR) or be within 6 months of confirmed entry from the date of interview. For further information or to apply for this exciting role, please contact the NHS Scotland International Recruitment Service: Telephone: +44141 278 2712 Email: [email protected] Web: www.international.scot.nhs.uk GLOSSARY AHP Allied Health Profession BPSD Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia CAMHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service CAPA Choice and Partnership Approach CBT Cognitive Behavioural Therapy CCT Certificate of Completion of Training CESR Certificate of Eligibility for Specialist Registration CPD Continuing Professional Development CPN Community Psychiatric Nurse DCC Direct Clinical Care EEA European Economic Area FBT Family Based Treatment GIRFEC Getting it Right for Every Child GMC General Medical Council HR Human Resources HSCP Health and Social Care Partnership IP Inpatient(s) IPCU Intensive Psychiatric Care Unit LD Learning Disabilities MRCPsych Member of the Royal College of Psychiatry NHS National Health Service OOH Out of Hours OP Outpatient(s) PA Programmed Activity PVG Protection of Vulnerable Groups RMN Registered Mental Nurse SCA Scottish Centre for Autism SPA Supporting Professional Activity UK United Kingdom WTE Whole Time Equivalent JOB DESCRIPTION NHS Grampian Consultant Psychiatrist General Adult Psychiatry General information The Mental Health Services Clinical Management Board of NHS Grampian is responsible for the provision of psychiatric services to Aberdeen City, Aberdeenshire, Moray and to Orkney. -

Scotland) 15 June 2021

Version 1.6 (Scotland) 15 June 2021 ISARIC/WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK (Scotland) Recruitment Procedures for FRONTLINE CLINICAL RESEARCH STAFF The most up to date versions of the protocol and case report form are available at isaric4c.net/protocols/ A virtual site visit is available at isaric4c.net/virtual_site_visit/ AIM: Please recruit the following patients only: • Vaccine failure (positive COVID test - rather than displaying symptoms – >28d after having received a vaccine) • Reinfection (proven after proven) • Co-infection (flu/RSV) • COVID associated hyper inflammation (MIS-A/MIS-C/PINS-TS) at any age • Samples from patients with pathogens of public health interest including people identified as infected with SARS-CoV “variants of concern” • All children CONSENT: once the form is signed by a participant it is hazardous. To record consent, we suggest an independent witness observes the completed form then signs a fresh copy outside of the isolation area. Consent can also be obtained by telephone from participants or from relatives for proxy consent. RECRUITMENT PACKS: Sample collection kits will be supplied to sites. Sample collections kits can be requested from: [email protected] Each kit will have a specific kit ID number, with each component within showing this kit ID and its own respective component ID for audit purposes. Pods and bio-bags for shipping will also be supplied to sites. These can be requested from [email protected] OBTAIN SAMPLES according to the schedule. You can find out which tier you are operating at in the front page of the site file. If you have capacity to recruit at TIER 2: Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 28 days after discharge Samples R S S C Sample priority 1 2 3 4 R: recruitment sample; S: serial sample; C: convalescent sample.