Employment Tribunals (Scotland)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contract Between Scottish Ministers

CONTRACT BETWEEN SCOTTISH MINISTERS AND GEOAMEY PECS LTD FOR THE SCOTTISH COURT CUSTODY AND PRISONER ESCORT SERVICE (SCCPES) REFERENCE: 01500 MARCH 2018 Official No part of this document may be disclosed orally or in writing, including by reproduction, to any third party without the prior written consent of SPS. This document, its associated appendices and any attachments remain the property of SPS and will be returned upon request. 1 | P a g e 01500 Scottish Court Custody and Prisoner Escort Service (SCCPES) FORM OF CONTRACT CONTRACT No. 01500 This Contract is entered in to between: The Scottish Ministers, referred to in the Scotland Act 1998, represented by the Scottish Prison Service at the: Scottish Prison Service Calton House 5 Redheughs Rigg Edinburgh EH12 9HW (hereinafter called the “Purchaser”) OF THE FIRST PART And GEOAmey PECS Ltd (07556404) The Sherard Building, Edmund Halley Road Oxford OX4 4DQ (hereinafter called the “Service Provider”) OF THE SECOND PART The Purchaser hereby appoints the Service Provider and the Service Provider hereby agrees to provide for the Purchaser, the Services (as hereinafter defined) on the Conditions of Contract set out in this Contract. The Purchaser agrees to pay to the Service Provider the relevant sums specified in Schedule C and due in terms of the Contract, in consideration of the due and proper performance by the Service Provider of its obligations under the Contract. The Service Provider agrees to look only to the Purchaser for the due performance of the Contract and the Purchaser will be entitled to enforce this Contract on behalf of the Scottish Ministers. -

Mental Health Bed Census

Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Data Collection Documentation Document Type: Guidance Notes Collections: 1. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census: One Day Audit 2. Mental Health and Learning Disability Patients: Out of Scotland and Out of NHS Placements SG deadline: 30th November 2014 Coverage: Census date: Midnight, 29th Oct 2014 Page 1 – 10 Nov 2014 Scottish Government One Day Audit of Inpatient Bed Use Definitions for Data Recording VERSION 2.4 – 10.11.14 Document Details Issue History Version Status Authors Issue Date Issued To Comments / changes 1.0 Draft Moira Connolly, NHS Boards Beth Hamilton, Claire Gordon, Ellen Lynch 1.14 Draft Beth Hamilton, Ellen Lynch, John Mitchell, Moira Connolly, Claire Gordon, 2.0 Final Beth Hamilton, 19th Sept 2014 NHS Boards, Ellen Lynch, Scottish John Mitchell, Government Moira Connolly, website Claire Gordon, 2.1 Final Ellen Lynch 9th Oct 2014 NHS Boards, Further clarification included for the following data items:: Scottish Government Patient names (applicable for both censuses) website ProcXed.Net will convert to BLOCK CAPITALS, NHS Boards do not have to do this in advance. Other diagnosis (applicable for both censuses) If free text is being used then separate each health condition with a comma. Mental Health and Learning Disability Bed Census o Data item: Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis on admission Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option. o Data item: Last known Mental Health/Learning Disability diagnosis Can use full description option or ICD10 code only option. -

Grampian Hospitals Art Trust (GHAT) Artroom Evaluation Report

Grampian Hospitals Art Trust (GHAT) Artroom Evaluation Report Aberdeen June 2018 By: Imran Arain, Health Promoting Health Services and Public Mental Health Lead Helle Buch Larsen, Regional Researcher - Childsmile (North Region) Emma Williams Health Improvement Practitioner - Senior Directorate of Public Health, NHS Grampian 1 Table of Contents Section Contents Page Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations and terms used in the report 5 How to read refined CMOs (Context Mechanism & Outcome) in Results 6 section Lists of Tables 7 List of Figures 8 Executive Summary 9 1.0 Introduction 11 2.0 Background and context 11 2.1 Artroom delivery plan/model 12 2.2 Main hospitals covered and the resources deployed 12 2.2.1 Main funding support sources 13 3.0 Purpose, aims and objectives of the evaluation 13 3.1 Purpose 13 3.2 Research question 13 3.3 Specific aims, objectives and outcomes 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Evaluation approach 14 4.2 The outcomes to be evaluated to assess Artroom 14 4.3 Methodological approach 14 4.3.1 Scientific Realistic Evaluation: roots with ‘realist’ philosophy 15 4.3.2 Overall methodology 16 4.4 Application of SRE to the study 17 5.0 Methods and Process 19 5.1 Document analysis and literature review to develop Artroom 19 programme theory- Phase 1 5.2 In-depth Interviews – Phase 2 19 5.2.1 Constructing sample and selecting participants for in-depth interviews 21 and analysis 5.3 Survey- Phase 2 22 5.3.1 Constructing the sample, selecting participants for the survey and 22 analysis 5.4 Observational data 22 6.0 Ethics and ethical -

MASTER) Hospital List (Updated October 2015

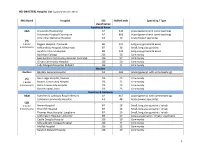

HEI (MASTER) Hospital List (updated October 2015) NHS Board Hospital ISD Staffed beds Speciality / Type classification Ayrshire & Arran A&A University Hospital Ayr A2 343 Acute (general with some teaching) University Hospital Crosshouse A2 666 Acute (general with some teaching) Arran War Memorial Hospital A3 19 Acute (mixed speciality) (9) 3 acute Biggart Hospital, Prestwick B6 121 Long stay geriatric & acute 6 community Kirklandside Hospital, Kilmarnock B7 36 Small, long stay geriatric Ayrshire Central Hospital B8 142 Long stay geriatric & acute Davidson Cottage J26 26 Community East Ayrshire Community Hospital, Cumnock J26 57 Community Girvan Community Hospital J26 20 Community Lady Margaret Hospital, Millport J26 9 Community Borders Borders Borders General Hospital A2 265 Acute (general, with some teaching) (5) Hay Lodge Hospital, Peebles J26 23 Community 1 acute Hawick Community Hospital J26 22 Community 4 community Kelso Community Hospital J26 23 Community Knoll Hospital, Duns J26 23 Community Dumfries & Galloway D&G Dumfries & Galloway Royal Infirmary A2 367 Acute (general, with some teaching) Galloway Community Hospital A3 48 Acute (mixed speciality) (10) 2 acute Annan Hospital B7 18 Small, long stay geriatric / rehab 8 community Thornhill Hospital B7 13 Small, long stay geriatric / rehab Thomas Hope Hospital, Langholm B7 10 Small, long stay geriatric / rehab Lochmaben Hospital, Lockerbie B9 17 Long stay geriatric / rehab / psychiatry Castle Douglas Hospital J26 19 Community Kirkcudbright Cottage Hospital J26 9 Community Moffat Hospital J26 12 Community Newton Stewart Hospital J26 19 Community 1 HEI (MASTER) Hospital List (updated October 2015) Fife Fife Victoria Hospital, Kirkcaldy A2 621 Acute (general with some teaching) (7) Queen Margaret Hospital, Dunfermline A3 196 Acute (mixed speciality) 2 acute 5 community Cameron Hospital, Leven B7 95 Small, long stay geriatric Adamson Hospital, Cupar J26 19 Community Glenrothes Hospital J26 74 Community Randolph Wemyss Memorial Hospital J26 16 Community St. -

Scotland) 15 June 2021

Version 1.6 (Scotland) 15 June 2021 ISARIC/WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK (Scotland) Recruitment Procedures for FRONTLINE CLINICAL RESEARCH STAFF The most up to date versions of the protocol and case report form are available at isaric4c.net/protocols/ A virtual site visit is available at isaric4c.net/virtual_site_visit/ AIM: Please recruit the following patients only: • Vaccine failure (positive COVID test - rather than displaying symptoms – >28d after having received a vaccine) • Reinfection (proven after proven) • Co-infection (flu/RSV) • COVID associated hyper inflammation (MIS-A/MIS-C/PINS-TS) at any age • Samples from patients with pathogens of public health interest including people identified as infected with SARS-CoV “variants of concern” • All children CONSENT: once the form is signed by a participant it is hazardous. To record consent, we suggest an independent witness observes the completed form then signs a fresh copy outside of the isolation area. Consent can also be obtained by telephone from participants or from relatives for proxy consent. RECRUITMENT PACKS: Sample collection kits will be supplied to sites. Sample collections kits can be requested from: [email protected] Each kit will have a specific kit ID number, with each component within showing this kit ID and its own respective component ID for audit purposes. Pods and bio-bags for shipping will also be supplied to sites. These can be requested from [email protected] OBTAIN SAMPLES according to the schedule. You can find out which tier you are operating at in the front page of the site file. If you have capacity to recruit at TIER 2: Day 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 28 days after discharge Samples R S S C Sample priority 1 2 3 4 R: recruitment sample; S: serial sample; C: convalescent sample. -

Health Promoting Health Services

Health Promoting Health Services Drop in sessions for staff These sessions are organised to raise awareness about Health Promoting Health Service web training and development resources. Health Promoting Health Service (HPHS) is a settings-based health promotion approach which aims to support the development of a health promoting culture and embed effective health improvement practice within NHS Grampian. Working closely with hospital and community health and social care colleagues we will improve and develop public health policy and practice within a range of settings including hospitals. All NHS Grampian staff are invited to come along to participate in the drop in sessions. Hospital Date and time Venue Aberdeen Royal 1. March 7 Medical Lecture Theatre (Purple Zone Infirmary 10.00am – 14.00 pm ARI) 2. April 18 10.00-14.00pm Medical Lecture Theatre (Purple Zone Maternity Hospital ARI 3. May 26 ARI) 10.00-14.00pm MacGillivray Conference Room Woodend Hospital March 14 Deveron Room 10.00-14.00pm Inverurie Hospital April 25 Small Conf Room, Staff Home 10.00-14.00pm Fraserburgh March 23 Conference Rooms 1 & 2 10.00-14.00 Ugie Hospital Peterhead April 26 Meeting Room, Collieburn Day 1300-1600 Centre, Format of the drop in sessions 1. There is no specific timing to drop in, please come along even if you have only a few minutes. 2. An optional 5-10 minute HPHS raising the issue brief and website show up after every 90 minutes followed by question and answer session. 3. Individual/group visit through the HPHS website and available resources using laptop/ipad with the support of HPHS colleagues For more detail contact – Imran Arain, HPHS lead, [email protected] , 01224558482 . -

Mental Health Bed Census 2017

Inpatient Census 2017 Mental Health and Learning Disability Inpatient Bed Census (Part 1) Document Version 2017/1.0 Page | 1 Document Type: Guidance Notes (Version 2017/1.0) Produced by Health & Social care Analysis Division (HSCA) (Scottish Government) Collections: 1. Mental Health and Learning Disability Inpatient Bed Census SG deadline: 31st May 2017 Coverage: Census date: Midnight, (end of) 30th March 2017 Page | 2 Document Details Issue History Version Status Authors Issue Date Issued To Comments / changes 0.1 Ellen Lynch (on 15 Feb 2017 behalf of Working Group, HSCA, Scottish Government) 0.2 Ellen Lynch & 21 Feb 2017 Guy McGivern (on behalf of Working Group, HSCA, Scottish Government) 1.0 Ellen Lynch & 28th Feb 2017 NHS Boards Guy McGivern (on behalf of Working Group, HSCA, Scottish Government) Page | 3 Contents Scope of the Inpatient Census ..........................................................................................................................................................5 Mental Health and Learning Disability Inpatient Bed Census (Part 1) Inclusion Criteria .............................................................6 Mental Health, Addiction and Learning Disability Patients: Out of NHS Scotland Placements Census (Part 2) Inclusion Criteria .................................................................................................................................................................................................7 Hospital Based Complex Clinical Care Census (Part 3) Inclusion Criteria -

Partnership Improvement and Outcomes Division.Dot

Balance of Care / Continuing Care Census Definitions and data recording manual Revised September 2009 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of this Paper 3 1.2 Background 3 1.3 Coverage and context of census 3 2 Data Requirements 2.1 Census Data 4 2.2 Census Date 4 2.3 Data Quality 4 2.4 Guidance for Data Input 4 2.4.1 Example of Excel Spreadsheet 4 3 NHS Continuing Care Census Data Items 3.1 Location Code 5 3.2 Location Name 5 3.3 CHI (Community Health Index) 6 3.4 Patient Identifier 6 3.5 Patient Name 7 3.6 Gender 7 3.7 Date of Birth 7 3.8 Date of Admission 8 3.9 Ethnicity 9 3.10 Speciality 10 3.11 Patient’s Postcode of Home address 12 3.12 Patient’s town/city of residence (if postcode unavailable) 12 3.13 Patient’s area of town/city (only required for larger cities, only required if postcode unavailable) 13 3.14 Delayed Discharge check (Y/N) 13 4 Submissions of Data 4.1 Census Data Collection 14 4.2 Date of Submission 14 4.3 Method of Submission 14 5 Contacts 5.1 NHS National Services Scotland 15 6 Appendix 1 What is NHS Continuing Health care Appendix 2 Location codes reported at previous census Version 3.3, September 2009 2 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of this Paper This paper provides guidance to NHS Boards on definitions, procedures and information concerning the Balance of Care / Continuing Care Census. 1.2 Background There is no method for identifying all patients who are receiving NHS care that is on-going non-acute care, delivered as an inpatient, and often over an extended period, in whatever setting (including hospice or care home). -

Court Custody and Prisoner Escort Services in Scotland

COURT CUSTODY AND PRISONER ESCORT SERVICES IN SCOTLAND CONTRACT NUMBER 00846 Court Custody and Prisoner Escort Services Contract Number 00846 Contract Number 00846 March 2011 FORM OF CONTRACT: CONTRACT NO. 00846 This Contract is entered in to between: The Scottish Ministers, referred to in the Scotland Act 1998, represented by the Scottish Prison Service at the Scottish Prison Service Calton House 5 Redheughs Rigg Edinburgh EH12 9HW (hereinafter called “Purchaser” or the “SPS”) OF THE FIRST PART and G4S Care and Justice Services (UK) Limited (Company Registration number 0390328) whose registered office is: Sutton Park 15 Carshalton Road Sutton Surrey SM1 4LD (hereinafter called the “Service Provider” or “G4S“) OF THE SECOND PART The Purchaser hereby appoints the Service Provider and the Service Provider hereby agrees to provide for the Purchaser the Services (as hereinafter defined) on the terms and conditions set out in this Contract. The Purchaser agrees to pay to the Service Provider the relevant Prices specified in Schedule C and due in terms of the Contract, in consideration of the due and proper performance by the Service Provider of its obligations under the Contract. The Service Provider agrees to look only to the Purchaser for the due performance of the Contract and the Purchaser will be entitled to enforce this Contract on behalf of the Scottish Ministers. The Contract shall consist of this Form of Contract and the following documents attached hereto which shall be deemed to form and to be read and to be construed as part of the Contract. In the event of conflicts between the documents forming the Contract, the documents shall take precedence in the order listed: (i) Form of Contract; (ii) Schedule A; Terms & Conditions of Contract (iii) Schedule B; Specification (iv) Schedule C; Pricing (v) Schedule D; Performance Measures (vi) Schedule E; Premises (vii) Schedule F; Service Provider’s Proposal. -

Mental Health Bed Census

Inpatient Census 2018 Mental Health and Learning Disability Inpatient Bed Census (Part 1) Document Version 2018/1.0 Page | 1 Document Type: Guidance Notes (Version 2018/1.0) Produced by Health & Social Care Analysis Division (HSCA) (Scottish Government) Collections: 1. Mental Health and Learning Disability Inpatient Bed Census SG deadline: 31st May 2018 Coverage: Census date: Midnight, (end of) 28th March 2018 Page | 2 Document Details Issue History Version Status Authors Issue Date Issued To Comments / changes 0.1 Guy McGivern 02 Feb 2018 (on behalf of Working Group, HSCA, Scottish Government) 0.2 Guy McGivern 19 Feb 2018 Incorporated comments from ScotXed. (on behalf of Working Group, HSCA, Scottish Government) 1.0 Guy McGivern 01 Mar 2018 NHS Boards (on behalf of Working Group, HSCA, Scottish Government) Page | 3 Contents Scope of the Inpatient Census ..........................................................................................................................................................5 Mental Health and Learning Disability Inpatient Bed Census (Part 1) Inclusion Criteria .............................................................6 Mental Health, Addiction and Learning Disability Patients: Out of NHS Scotland Placements Census (Part 2) Inclusion Criteria .................................................................................................................................................................................................7 Hospital Based Complex Clinical Care Census (Part 3) Inclusion -

The Grampian Healthcare National Health Service Trust (Establishment) Order 1992

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1992 No. 3315 (S.273) NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE, SCOTLAND The Grampian Healthcare National Health Service Trust (Establishment) Order 1992 22nd December Made - - - - 1992 Coming into force - - 1st January 1993 The Secretary of State, in exercise of powers conferred on him by sections 12A(1) and (4) of and paragraphs 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6(2)(d) of Schedule 7A to the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978(1) and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, having received and considered the results of the consultation carried out by Grampian Health Board with the bodies specified in regulation 3 of the National Health Service Trusts (Consultation before Establishment) (Scotland) Regulations 1991(2), hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Grampian Healthcare National Health Service Trust (Establishment) Order 1992 and shall come into force on 1st January 1993. (2) In this Order unless the context otherwise requires— “the Act” means the National Health Service (Scotland) Act 1978(3); “establishment date” means 1st January 1993; “operational date” has the meaning assigned to it in paragraph 3(1)(e) of Schedule 7A to the Act(4); “the trust” means the Grampian Healthcare National Health Service Trust established by article 2 of this Order. Establishment of the trust 2. There is hereby established an NHS trust which shall be called the Grampian Healthcare National Health Service Trust. -

Partnership Improvement and Outcomes Division.Dot

Balance of Care / Continuing Care Census Definitions and data recording manual Updated February 2013 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of this Paper 3 1.2 Background 3 1.3 Coverage and context of census 3 2 Data Requirements 2.1 Census Data 4 2.2 Census Date 4 2.3 Data Quality 4 2.4 Guidance for Data Input 4 2.4.1 Example of Excel Spreadsheet 5 3 NHS Continuing Care Census Data Items 3.1 Location Code 6 3.2 Location Name 6 3.3 Ward 6 3.4 CHI (Community Health Index) 6 3.5 Patient Identifier 6 3.6 Patient Name 6 3.7 Gender 7 3.8 Date of Birth 7 3.9 Date of Admission 7 3.10 Ethnicity 8 3.11 Speciality 9 3.12 Patient’s Postcode of Home address 11 3.13 Patient’s town/city of Home address (only required if postcode is unavailable) 11 3.14 Patient’s area of town/city (only required if the postcode is unavailable and Glasgow or Edinburgh) 11 3.15 Delayed Discharge check 11 4 Submissions of Data 4.1 Census Data Collection 12 4.2 Date of Submission 12 4.3 Method of Submission 12 5 Contacts 5.1 NHS National Services Scotland 13 Appendix 1 What is NHS Continuing Health care? 14 Appendix 2 Location codes reported at March 2012 census 15 Version 3.4, February 2013 2 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of this Paper This paper provides guidance to NHS Boards on definitions, procedures and information concerning the Balance of Care / Continuing Care Census.