How Changing Lifestyles Impact Seri Smellscapes and Smell Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Satellite Monitoring of Coastal Marine Ecosystems a Case from the Dominican Republic

Satellite Monitoring of Coastal Marine Ecosystems: A Case from the Dominican Republic Item Type Report Authors Stoffle, Richard W.; Halmo, David Publisher University of Arizona Download date 04/10/2021 02:16:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/272833 SATELLITE MONITORING OF COASTAL MARINE ECOSYSTEMS A CASE FROM THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Edited By Richard W. Stoffle David B. Halmo Submitted To CIESIN Consortium for International Earth Science Information Network Saginaw, Michigan Submitted From University of Arizona Environmental Research Institute of Michigan (ERIM) University of Michigan East Carolina University December, 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables vi List of Figures vii List of Viewgraphs viii Acknowledgments ix CHAPTER ONE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 The Human Dimensions of Global Change 1 Global Change Research 3 Global Change Theory 4 Application of Global Change Information 4 CIESIN And Pilot Research 5 The Dominican Republic Pilot Project 5 The Site 5 The Research Team 7 Key Findings 7 CAPÍTULO UNO RESUMEN GENERAL 9 Las Dimensiones Humanas en el Cambio Global 9 La Investigación del Cambio Global 11 Teoría del Cambio Global 12 Aplicaciones de la Información del Cambio Global 13 CIESIN y la Investigación Piloto 13 El Proyecto Piloto en la República Dominicana 14 El Lugar 14 El Equipo de Investigación 15 Principales Resultados 15 CHAPTER TWO REMOTE SENSING APPLICATIONS IN THE COASTAL ZONE 17 Coastal Surveys with Remote Sensing 17 A Human Analogy 18 Remote Sensing Data 19 Aerial Photography 19 Landsat Data 20 GPS Data 22 Sonar -

The Reduction of Seri Indian Range and Residence in the State of Sonora, Mexico (1563-Present)

The reduction of Seri Indian range and residence in the state of Sonora, Mexico (1563-present) Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bahre, Conrad J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 15:06:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551967 THE REDUCTION OF SERI INDIAN RANGE AND RESIDENCE IN THE STATE OF SONORA, MEXICO (1536-PRESENT) by Conrad Joseph Bahre A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 7 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowl edgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the inter ests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Protocolo Comunitario Biocultural Territorio Comcáac Pliego.Pdf

El presente material es resultado de un proceso de construcción comunitaria. Cualquier uso indebido y sin el permiso expreso de sus autores, infringe las leyes nacionales e internacionales de propiedad intelectual. Comunitario Biocultural del Territorio Comcáac, Punta Chueca y El Desemboque, Sonora, México, 2018. PNUD, SEMARNAT, RITA, Comisión Técnica Comunitaria de Comcáac 2018. Protocolo Comunitario Biocultural del Territorio Comcáac, Punta Chueca y El Desemboque, Sonora, para la gestión de los recursos genéticos y su conocimiento tradicional en el ámbito del Protocolo de Nagoya. México. Paginas totales 98 Ejemplar gratuito. Prohibida su venta. Impreso en México PROTOCOLO COMUNITARIO BIOCULTURAL DEL TERRITORIO COMCÁAC Instrumento sobre nuestros usos y costumbres para la protección de nuestro territorio, conocimientos y prácticas tradicionales, recursos Este producto es resultado del proyecto Fortalecimiento de las Capacidades Nacionales para la Implementación del biológicos y genéticos. Protocolo de Nagoya sobre acceso a los Recursos Genéticos y la Participación Justa y Equitativa en los Beneficios que se deriven de su Utilización del Convenio sobre Diversidad Biológica, implementado nacionalmente entre el Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo y la Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales de México, con el apoyo financiero del Fondo Mundial para el Medio Ambiente, a través de la Red Indígena de Turismo de México A.C. y la Comunidad Indígena del Territorio Comcáac, Punta Chueca y El Desemboque, Sonora Punta Chueca -

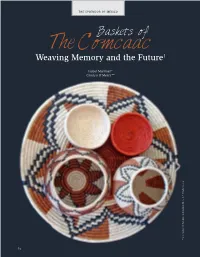

Baskets of the Comcaac Weaving Memory and the Future1

THE SPLENDOR OF MEXICO Baskets of The Comcaac Weaving Memory and the Future1 Isabel Martínez* Carolyn O’Meara** Photo courtesy of the Lutisuc Asociación Cultural I.A.P., www.lutisuc.org. Photo courtesy of the Lutisuc Asociación Cultural I.A.P., 74 Photo courtesy of the Lutisuc Asociación Cultural I.A.P., www.lutisuc.org. I.A.P., Cultural Asociación Lutisuc the of courtesy Photo The limberbush branches, the raw materials, are gathered in the desert: the women go out alone or in family groups, either walking or organizing themselves to go in a pick-up truck. he Seris or Comcaac, as they call themselves, are an century, the Seris’ lifestyle, based on hunting, fishing, and gath- indigenous people of approximately 900 individuals ering, as well as their social organization, changed, and with Tliving in the towns of Punta Chueca (Socaaix), in the it, so did the role of basket-weaving. In El Desembo que, one municipality of Hermosillo, and El Desemboque del Río of the main sources of women’s economic earnings is the San Ignacio (or El Desemboque de los Seris) (Haxöl Iihom), sale of basket wares. In addition to caring for their families and in the municipality of Pitiquito, both along the Gulf of Ca l- doing the housework and, in some cases, gathering food in ifor nia coast in the state of Sonora, Mexico. They speak Seri the desert, some women spend a large part of their days at this or Cmiique Iitom, Spanish, and in some cases, English. In task. In addition to their economic value, the baskets contin- their daily lives they speak Cmiique Iitom, which is how they ue to be one of the most important objects in their lives. -

Seris De Sonora

Proyecto Perfiles Indígenas de México, Documento de trabajo. Seris de Sonora. Acosta, Gabriela. Cita: Acosta, Gabriela (2002). Seris de Sonora. Proyecto Perfiles Indígenas de México, Documento de trabajo. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/salomon.nahmad.sitton/74 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons. Para ver una copia de esta licencia, visite https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.es. Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social Pacífico Sur PERFILES INDÍGENAS DE MÉXICO PERFIL INDÍGENA: SERIS DE SONORA INVESTIGADOR: Gabriela Acosta COORDINACIÓN GENERAL DEL PROYECTO: Salomón Nahmad y Abraham Nahón PERFILES INDIGENAS DE MÉXICO / SERIS DE SONORA / GABRIELA ACOSTA SERIS DE SONORA Foto 1. Isla Tiburón UBICACIÓN GEOGRÁFICA El territorio Seri está situado en la costa central del estado de Sonora, entre los 28 45 y 29 41 de latitud Norte y los 112 10 y 112 36 de longitud Oeste. Limita al Norte con la región de Puerto Libertad, y al sur con Bahía de Kino, al este con los campos agrícolas de Hermosillo y al Oeste con el Golfo de California o Mar Cortés. Las aguas patrimoniales Seris, con aproximadamente 100 Km de litorales se localizan en la parte Sur de la región septentrional del Golfo de California, y en la costa central del estado de Sonora. -

The Management of Linguistic Diversity and Peace Processes La Gestion De La Diversité Linguistique Et Les Processus De Paix

La gestíó de la díversítat lingüistica i els processes de pau La gestión de la diversidad lingüística y los procesos de paz The Management of Linguistic Diversity and Peace Processes La gestion de la diversité linguistique et les processus de paix CENTRE UNESCO DE CATALUNYA I | UNESCOCAT 1« Oéroa > la CAfltra La gestíó de la díversítat lingüistica i els processes de pau Col-lecció Arguments, número i © 2010 Centre UNESCO de Catalunya-Unescocat. Centre UNESCO de Catalunya-Unescocat Nàpois, 346 08025 Barcelona www.unescocat.org El seminari sobre La gestíó de la díversítat lingüística i els processes de pau. Una panoràmica internacional amb estudis de cas, va rebre el suport de: ^ Generalität de Catalunya Il Departament Zi de la Vicepresidència Generalität de Catalunya Departament d’lnterior, Ä Relacions Institucionals i Patlicipaciö Oficina de Promociö de la Pau i dels Drets Humans L’edició d’aquest llibre ha rebut el suport de: LINGUA CASA Traduccions: Marc Alba, Kelly Dickeson, Kari Friedenson, Ariadna Gobema, Alain Hidoine, Enne Kellie, Marta Montagut, Jordi Planas, Nuria Ribera, Raquel Rico, Jordi Trilla. Revisions linguistiques: Kari Friedenson, Ariadna Goberna, Alain Hidoine, Patricia Ortiz. Disseny: Kira Riera Maquetació: Montflorit Edicions i Assessoraments, si. Impressió: Gramagraf, sed. Primera edició: gener de 2010 ISBN: 978-84-95705-93-8 Dipósit legal: B-5436-2010 Fotografía de la coberta: ©iStockphoto.com/ Yenwen Lu CONTENTS The Management of Linguistic Diversity and Peace Processes Foreword 247 Introduction 249 Parti 01 Multilingualism -

Two Annotated Short Seri Texts

SIL-Mexico Electronic Working Papers #019: Two annotated short Seri texts Stephen A. Marlett Marlett, Stephen A. 2015. Two annotated short Seri texts. SIL-Mexico Branch Electronic Working Papers #19. [http://mexico.sil.org/resources/archives/62746] (©) SIL International These working papers may be periodically updated, expanded, or corrected. Comments may be sent to the author at: [email protected]. 2 SIL-Mexico Electronic Working Papers #019:Two annotated short Seri texts General introduction Two annotated short texts in the Seri language—Cmiique Iitom—(ISO 639-3 code [sei]) are pre- sented, with introductions to each, in appendices A and B.1 The first text is based on an oral nar- ration recorded at least forty years ago and the second one is a composition written about fifteen years ago. In these presentations, the texts are written in the practical orthography used in the community; this is the first line of each interlinear group. The phonetic values of the symbols are explained in appendix C. The small marks ˻ and ˼ are used to set off words that form lexicalized expressions (idioms and compounds), most of which receive either subentry or main entry treatment in M. Moser & Marlett (2010); these symbols are not part of the practical orthography. The second line of the interlinear group gives the morphological makeup of the words. Morpheme breaks are not indicated in these lines since it would be misleading or ponderous to do so given the way words are composed; see Marlett (1981, 1990, in preparation) for more information about the morphology. The punctuation used in the glossing of the morphemes generally follows the Leipzig Glossing Rules.2 In this case, the semicolon indicates that the morpheme break between the two morphemes is not one that could be easily shown based on the surface form.3 In order to illustrate the glossing conventions used here, we can look at the word cöihataamalca that appears in the title of the text in appendix A. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of SONORA (Vers

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SONORA (Vers. 14 May 2019) © Richard C. Brusca topographically, ecologically, and biologically NOTE: Being but a brief overview, this essay cannot diverse. It is the most common gateway state do justice to Sonora’s long and colorful history; but it for visitors to the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of hopefully provides a condensed introduction to this California). Its population is about three million. marvelous state. Readers with a serious interest in Sonora should consult the fine histories and The origin of the name “Sonora” is geographies of the region, many of which are cited in unclear. The first record of the name is probably the References section. The topic of Spanish colonial that of explorer Francisco Vásquez de history has a rich literature in particular, and no Coronado, who passed through the region in attempt has been made to include all of those 1540 and called part of the area the Valle de La citations in the References (although the most targeted and comprehensive treatments are Sonora. Francisco de Ibarra also traveled included). Also see my “Bibliography on the Gulf of through the area in 1567 and referred to the California” at www.rickbrusca.com. All photographs Valles de la Señora. by R.C. Brusca, unless otherwise noted. This is a draft chapter for a planned book on the Sea of Cortez; Four major river systems occur in the state the most current version of this draft can be of Sonora, to empty into the Sea of Cortez: the downloaded at Río Colorado, Río Yaqui, Río Mayo, and http://rickbrusca.com/http___www.rickbrusca.com_ind massive Río Fuerte. -

Inventory, Monitoring and Impact Assessment of Marine Biodiversity in the Seri Indian Territory, Gulf of California, Mexico

INVENTORY, MONITORING AND IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF MARINE BIODIVERSITY IN THE SERI INDIAN TERRITORY, GULF OF CALIFORNIA, MEXICO by Jorge Torre Cosío ________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHYLOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES STUDIES In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 2 Sign defense sheet STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED:____________________________ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) and the Wallace Research Foundation provided fellowships to the author. The Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) (grant FB463/L179/97), World Wildlife Fund (WWF) México and Gulf of California Program (grants PM93 and QP68), and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (grant 2000-0351) funded this study. Administrative support for part of the funds was through Conservation International – México (CIMEX) program Gulf of California Bioregion and Conservación del Territorio Insular A.C. -

Is for Aboriginal

Joseph MacLean lives in the Coast Salish traditional Digital territory (North Vancouver, British Columbia). A is for Aboriginal He grew up in Unama’ki (Cape Breton Island, Nova By Joseph MacLean Scotia) until, at the age of ten, his family moved to Illustrated by Brendan Heard the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Territory (Montréal). Joseph is an historian by education, a storyteller by Is For Zuni A Is For Aboriginal avocation and a social entrepreneur by trade. Is For Z “Those who cannot remember the past are His mother, Lieut. Virginia Doyle, a WWII army Pueblo condemned to repeat it.” nurse, often spoke of her Irish grandmother, a country From the Spanish for Village healer and herbalist, being adopted by the Mi'kmaq. - George Santayana (1863-1952) Ancient Anasazi Aboriginal The author remembers the stories of how his great- American SouthwestProof grandmother met Native medicine women on her A is for Aboriginal is the first in the First ‘gatherings’ and how as she shared her ‘old-country’ A:shiwi is their name in their language Nations Reader Series. Each letter explores a knowledge and learned additional remedies from her The language stands alone name, a place or facet of Aboriginal history and new found friends. The author wishes he had written Unique, single, their own down some of the recipes that his mother used when culture. he was growing up – strange smelling plasters that Zuni pottery cured his childhood ailments. geometry and rich secrets The reader will discover some interesting bits of glaze and gleam in the desert sun history and tradition that are not widely known. -

Centro Y Sur Del Municipio Caborca, Estado De Sonora

SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO MEXICANO GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE SONORA INVENTARIO FÍSICO DE LOS RECURSOS MINERALES EN LA PORCIÓN NORTE- CENTRO Y SUR DEL MUNICIPIO CABORCA, ESTADO DE SONORA. MARZO, 2010 SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO MEXICANO GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO DE SONORA INVENTARIO FÍSICO DE LOS RECURSOS MINERALES EN LA PORCIÓN NORTE- CENTRO Y SUR DEL MUNICIPIO CABORCA, ESTADO DE SONORA. ELABORÓ: David Arturo Maraver Romero REVISÓ: José Antonio Sánchez González SUPERVISÓ: Amador Núñez Miranda MARZO, 2010 INDICE Pagina I. GENERALIDADES ..................................................................................................... 1 I.1. Introducción .............................................................................................................. 1 I.2. Objetivo .................................................................................................................... 2 II. MEDIO FÍSICO Y GEOGRÁFICO .............................................................................. 3 II.1. Breve bosquejo histórico ......................................................................................... 3 II.2. Localización y extensión .......................................................................................... 3 II.3. Vías de comunicación y acceso .............................................................................. 5 II.4. Fisiografía ............................................................................................................... 6 II.5. Hidrografía ............................................................................................................. -

Book Chronology

Kino Book Guide: Chronology and Maps "Padre Kino and the Trail to the Pacific" Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J (1645 - 1711) Chapter, page and map references to the Kino Book are underlined. General maps are without page references. 10 Aug. 1645 Jesuit missionary Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino. S.J. (1645 - 1711) is born Eusebio Chini, the only son of Francesco and Margherita Chini, in the village of Segno. Segno is located in the foothills of the southern Alps and 15 miles north of the historic city of Trent in present day Italy. 24 Oct. 1648 The Thirty Years War in Europe ends. 20 Nov. 1665 Joins the Jesuit order as a novice and for the next 12 years prepares for the priesthood. Kino studies and teaches mathematics, astronomy and other natural sciences at the universities of Landsberg, Freiburg, Ingolstadt and Hall am Inn in present day Germany and Austria. Before joining the Jesuits, Kino suffers from an illness that brings him close to death. He vows he will become a missionary if his patron saint, Francis Xavier, intercedes by sparing his life. St. Francis Xavier (1506–1552) was a co-founder of the Jesuits and was its pioneering missionary to Asia. He ministered for 10 years in India and then worked in the East Indies and Japan and died as he was traveling to China. He was canonized as a saint in 1622. 11 Jun. 1677 Ordained a Roman Catholic priest in Ottingen (Altottingen) in present day Germany. Kino continues his pastoral ministry and teaching. May 1678 to Jan. 1681 After 8 years of petitioning his Jesuit superiors, Kino is granted permission to become a missionary.