Two Annotated Short Seri Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T1118-MDE-Moreno-La Inferencia.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD ANDINA SIMON BOLIVAR. SEDE ECUADOR. Área de Derecho Programa de Maestría en Derecho mención Derecho Constitucional ! LA INFERENCIA DE LA GARANTÍA DEL CONTENIDO ESENCIAL EN LA CONSTITUCION ECUATORIANA DEL 2008. j I SANTIAGO MORENO YANES. I , Quito- Ecuador I 2012 I t 1 '1 J CLAUSULA DE CESION DE DERECHO DE PUBLICACION DE TESISIMONOGRAFIA Yo, (SANTIAGO XAVIER MORENO y ANES), autor/a de la tesis intitulada (LA INFERENCIA DE LA GARANTÍA DEL CONTENIDO ESENCIAL EN LA CONSTITUCION ECUATORIANA DEL 2008.) mediante el presente documento dejo constancia de que la obra es de mi exclusiva autoría y producción, que la he elaborado para cumplir con uno de los requisitos previos para la obtención del titulo de (magíster en derecho mención derecho constitucional) en la Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Sede Ecuador. 1. Cedo a la Universidad ~dina Simón Bolívar, Sede Ecuador, los derechos exclusivos de reproducción, comunicación pública, distribución y divulgación, durante 36 meses a partir de mi graduación, pudiendo por 10 tanto la Universidad, utilizar y usar esta obra por cualquier medio conocido o por conocer, siempre y cuando no se 10 haga para obtener beneficio económico. Esta autorización incluye la reproducción total o parcial en los formatos virtual, electrónico, digital, óptico, como usos en red local y en internet. 2. Declaro que en caso de presentarse cualquier reclamación de parte de terceros respecto de los derechos de antor/a de la obra antes referida, yo asumiré toda responsabilidad frente a terceros y a la Universidad. 3. En esta fecha entrego a la Secretaria General, el ejemplar ~ respectivo y sus anexos en formato impreso y digital o electrónico. -

Protocolo Comunitario Biocultural Territorio Comcáac Pliego.Pdf

El presente material es resultado de un proceso de construcción comunitaria. Cualquier uso indebido y sin el permiso expreso de sus autores, infringe las leyes nacionales e internacionales de propiedad intelectual. Comunitario Biocultural del Territorio Comcáac, Punta Chueca y El Desemboque, Sonora, México, 2018. PNUD, SEMARNAT, RITA, Comisión Técnica Comunitaria de Comcáac 2018. Protocolo Comunitario Biocultural del Territorio Comcáac, Punta Chueca y El Desemboque, Sonora, para la gestión de los recursos genéticos y su conocimiento tradicional en el ámbito del Protocolo de Nagoya. México. Paginas totales 98 Ejemplar gratuito. Prohibida su venta. Impreso en México PROTOCOLO COMUNITARIO BIOCULTURAL DEL TERRITORIO COMCÁAC Instrumento sobre nuestros usos y costumbres para la protección de nuestro territorio, conocimientos y prácticas tradicionales, recursos Este producto es resultado del proyecto Fortalecimiento de las Capacidades Nacionales para la Implementación del biológicos y genéticos. Protocolo de Nagoya sobre acceso a los Recursos Genéticos y la Participación Justa y Equitativa en los Beneficios que se deriven de su Utilización del Convenio sobre Diversidad Biológica, implementado nacionalmente entre el Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo y la Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales de México, con el apoyo financiero del Fondo Mundial para el Medio Ambiente, a través de la Red Indígena de Turismo de México A.C. y la Comunidad Indígena del Territorio Comcáac, Punta Chueca y El Desemboque, Sonora Punta Chueca -

German Institutional Aid to Spanish Students in Germany During the Second World War1

Przegląd Nauk HistoryczNycH 2020, r. XiX, Nr 2 https://doi.org/10.18778/1644-857X.19.02.07 XAVIER MORENO JULIÁ * ROVIRA I VIRGILI UNIVERSITY TARRAGONA https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5188-123X German institutional aid to Spanish students in Germany during the Second World War1 Abstract. during the second World War dr. edith Faupel intensively helped the spanish students and soldiers of the Blue division, the unit that fought in russia within the Wehrmacht troops. she was the wife of the first german ambassador in the National spain, general Wilhelm Faupel (1936–1937). Faupel was the director of the iberian-american institute and of the german-spanish society at a time. she and her husband fully served the regime of the National socialists during its existence in germany. the action of this woman and her motifs are studied in this article. it is also analysed how her activities were deter- mined by the changes on the fronts of World War ii. Keywords: second World War, diplomacy, spain, germany, third reich. rotected by her husband, the german ambassador to Nation- al spain, dr. edith Faupel provided assistance to spanish P students in germany through the two institutions of which her husband was president: the instituto iberoamericano (ibe- rian-american institute) and the sociedad germano-española (german-spanish society). an analysis of her activities can shed more light on german-spanish relations during the second World War, which were obviously affected by the progress of the conflict 2 in which both morale and funds decreased notably over time .3 * Department od History and History of art, e-mail: [email protected] 1 My gratitude goes to Professor dariusz Jeziorny, from university of lodz, for his interest in publishing the article. -

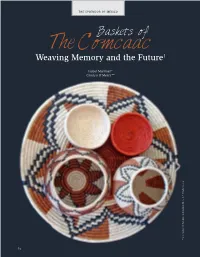

Baskets of the Comcaac Weaving Memory and the Future1

THE SPLENDOR OF MEXICO Baskets of The Comcaac Weaving Memory and the Future1 Isabel Martínez* Carolyn O’Meara** Photo courtesy of the Lutisuc Asociación Cultural I.A.P., www.lutisuc.org. Photo courtesy of the Lutisuc Asociación Cultural I.A.P., 74 Photo courtesy of the Lutisuc Asociación Cultural I.A.P., www.lutisuc.org. I.A.P., Cultural Asociación Lutisuc the of courtesy Photo The limberbush branches, the raw materials, are gathered in the desert: the women go out alone or in family groups, either walking or organizing themselves to go in a pick-up truck. he Seris or Comcaac, as they call themselves, are an century, the Seris’ lifestyle, based on hunting, fishing, and gath- indigenous people of approximately 900 individuals ering, as well as their social organization, changed, and with Tliving in the towns of Punta Chueca (Socaaix), in the it, so did the role of basket-weaving. In El Desembo que, one municipality of Hermosillo, and El Desemboque del Río of the main sources of women’s economic earnings is the San Ignacio (or El Desemboque de los Seris) (Haxöl Iihom), sale of basket wares. In addition to caring for their families and in the municipality of Pitiquito, both along the Gulf of Ca l- doing the housework and, in some cases, gathering food in ifor nia coast in the state of Sonora, Mexico. They speak Seri the desert, some women spend a large part of their days at this or Cmiique Iitom, Spanish, and in some cases, English. In task. In addition to their economic value, the baskets contin- their daily lives they speak Cmiique Iitom, which is how they ue to be one of the most important objects in their lives. -

Tim's Walker of the Week 50Km Men's Racewalk, Olympic

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2011/2012 Number 46 14 August 2012 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours : Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au/ TIM'S WALKER OF THE WEEK Last week's Walker of the Week was Jared Tallent with his great 7th place Olympic 20km walk with 1:20:02. For Jared, it was another fantastic top-eight finish and it was in the lesser of his two Olympic events. With the Olympic 50km event this week, Jared upped the ante even further, taking his second successive Olympic 50km silver medal and recording a 2+ minute PB time of 3:36:53, also breaking the Olympic record into the bargain. What a performance! Walker of the Week! 50KM MEN'S RACEWALK, OLYMPIC GAMES, THE MALL, LONDON, SATURDAY 11 AUGUST 2012 The men's Olympic 50km walk started at 9AM at the Mall in London and I was one of the many spectators who lined the 2km loop to cheer on the contestants. My report on the Men's 50km Race Walk is taken from that of Dave Martin for the IAAF (see http://www.iaaf.org/Mini/OLY12/News/NewsDetail.aspx?id=67421) Sergey Kirdyapkin, the man to be beaten having won the IAAF World Race Walking Cup in Saransk in May, shattered the existing record of 3:37:09 with a decisive victory. -

Nuevo Flamenco: Re-Imagining Flamenco in Post-Dictatorship Spain

Nuevo Flamenco: Re-imagining Flamenco in Post-dictatorship Spain Xavier Moreno Peracaula Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD Newcastle University March 2016 ii Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One The Gitano Atlantic: the Impact of Flamenco in Modal Jazz and its Reciprocal Influence in the Origins of Nuevo Flamenco 21 Introduction 22 Making Sketches: Flamenco and Modal Jazz 29 Atlantic Crossings: A Signifyin(g) Echo 57 Conclusions 77 Notes 81 Chapter Two ‘Gitano Americano’: Nuevo Flamenco and the Re-imagining of Gitano Identity 89 Introduction 90 Flamenco’s Racial Imagination 94 The Gitano Stereotype and its Ambivalence 114 Hyphenated Identity: the Logic of Splitting and Doubling 123 Conclusions 144 Notes 151 Chapter Three Flamenco Universal: Circulating the Authentic 158 Introduction 159 Authentic Flamenco, that Old Commodity 162 The Advent of Nuevo Flamenco: Within and Without Tradition 184 Mimetic Sounds 205 Conclusions 220 Notes 224 Conclusions 232 List of Tracks on Accompanying CD 254 Bibliography 255 Discography 270 iii Abstract This thesis is concerned with the study of nuevo flamenco (new flamenco) as a genre characterised by the incorporation within flamenco of elements from music genres of the African-American musical traditions. A great deal of emphasis is placed on purity and its loss, relating nuevo flamenco with the whole history of flamenco and its discourses, as well as tracing its relationship to other musical genres, mainly jazz. While centred on the process of fusion and crossover it also explores through music the characteristics and implications that nuevo flamenco and its discourses have impinged on related issues as Gypsy identity and cultural authenticity. -

Team Standings

23rd IAAF World Race Walking Cup Cheboksary Saturday 10 and Sunday 11 May 2008 50 Kilometres Race Walk MEN ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHL Team Standings ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC ATHLETIC 11 May 2008 8:00 1 2 POSMARK BIB COMPETITOR 1 28 ITALY 23:37:04 163 Alex SCHWAZER 83:49:21 155 Marco DE LUCA 183:53:46 152 Diego CAFAGNA 344:02:32 162 Dario PRIVITERA 564:20:10 157 Matteo GIUPPONI 2 29 MEXICO 53:47:55 194 Horacio NAVA 113:51:16 188 Mario Iván FLORES 133:51:29 199 Jesús SÁNCHEZ 173:53:42 191 Daniel GARCÍA 233:56:52 200 Omar ZEPEDA 3 30 SPAIN 4843:47:30 Mikel ODRIOZOLA 123:51:20 76 José Alejandro CAMBIL 143:52:31 80 Jesús Angel GARCÍA 334:02:09 86 Santiago PÉREZ 374:04:43 87 Francisco PINARDO 4 60 UKRAINE 103:50:30 268 Oleksiy KAZANIN 223:55:16 276 Oleksiy SHELEST 283:59:32 265 Sergiy BUDZA DNF 273 Ivan LOSEV DNF 275 Oleksandr ROMANENKO 5 71 LATVIA 93:49:50 175 Ingus JANEVICS 153:52:45 176 Igors KAZAKEVICS 474:12:13 177 Arnis RUMBENIEKS DNF 174 Vjaceslavs GRIGORJEVS 6 79 PORTUGAL 163:53:11 223 António PEREIRA 314:00:52 217 Augusto CARDOSO 324:01:05 218 Jorge COSTA 404:05:17 222 Pedro MARTINS DNF 224 Dionísio VENTURA Vladimir KANAYKIN (RUS) Disqualified - IAAF Rule 39.4 Issued Wednesday, -

Racewalker N

nwo 0 ... ::T - a, - · 3c .,,. 0 ~ Cl) :z, fl ... 3 • ::T0 ..- · D>:E - · Cl) - ti~0 .. "" RACEWALKER N ,. s VOLUME XL. NUMBER 5 COLUMBUS. OHIO JULY 200-' Seaman. Vaill Lead Olympic Trials Sacramento. Cal., July 17-18--Tim Seaman. John Nunn. and Kevin Eastlt:r will represent the U.S. in the 20 Km racewalk at the Athens Olympics m August. Teresa Vaill will apparently be the lone U.S. women m the 20 at Athens. With 26 of the nation's finest walkers competing over two days. those four separatt.'dthem selves. The Trials aren't the cut and dried affair they once were-finish in the top three and your on the team-now they arc co,nplicated by "A" and "8" standards. To send three athletes. they must all meet the A standard. A single athlete can go if they have met the slower "B" standard. The men's race on Saturday saw three men with the J\ 5tandard going into the rece. When they finished one-two-lluec. the team was set. In the women's race. only Joanne Dowhad the A standard. but she needed to win to insure hc1 place on the team When T.::rcsaVaill. who had a 13 standard going in. upset her on Sunday. Vaill made the learn-a Trial win trumps an A ~1andard. provided the winner has the R. lf you don't follow all that.jus t accept the fact th11tVaill is our rep1esentaiJve. (Although, at this writing. the USOC web site. lists Dowand not Vail!. That has 1101been explained. -

Ingenico Group Registration Document 2016

2016 REGISTRATION DOCUMENT INCLUDING THE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT CONTENTS CHAIRMAN'S MESSAGE 3 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL PROFILE 4 5 STATEMENTS DECEMBER 31, 2016 131 KEY FIGURES 6 5.1 Consolidated income statement 132 INGENICO GROUP IN THE WORLD IN 2016 8 5.2 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 133 5.3 Consolidated statement of fi nancial position 134 2016 IN 8 HIGHLIGHTS 10 5.4 Consolidated cash fl ow statement 136 HISTORY 12 5.5 Consolidated statement of change in equity 138 ORGANIZATIONAL CHART 5.6 Notes to the consolidated fi nancial statements 139 (AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2016) 14 5.7 Statutory auditors’ report on the consolidated fi nancial statements 193 PRESENTATION 1 OF THE GROUP 17 PARENT COMPANY FINANCIAL 6 STATEMENTS AT DECEMBER 31, 2016 195 1.1 Activity & strategy 18 1.2 Risk factors 28 6.1 Assets 196 6.2 Liabilities 197 6.3 Profi t and loss account 198 6.4 Notes to the parent company fi nancial statements 199 CORPORATE SOCIAL 2 RESPONSIBILITY 37 6.5 Statutory auditors’ report on the parent company annual fi nancial statements 219 2.1 CSR for Ingenico Group 38 6.6 Five-year fi nancial summary 220 2.2 Reporting scope and method 42 2.3 The Ingenico Group community 45 2.4 Ingenico Group’s contribution to society 53 COMBINED ORDINARY AND 2.5 Ingenico Group’s environmental approach 64 7 EXTRAORDINARY SHAREHOLDERS’ 2.6 Report by the independent third party, on the MEETING OF MAY 10, 2017 221 consolidated human resources, environmental and social information included in the management report 75 7.1 Draft agenda and proposed resolutions -

Seris De Sonora

Proyecto Perfiles Indígenas de México, Documento de trabajo. Seris de Sonora. Acosta, Gabriela. Cita: Acosta, Gabriela (2002). Seris de Sonora. Proyecto Perfiles Indígenas de México, Documento de trabajo. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/salomon.nahmad.sitton/74 Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons. Para ver una copia de esta licencia, visite https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.es. Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social Pacífico Sur PERFILES INDÍGENAS DE MÉXICO PERFIL INDÍGENA: SERIS DE SONORA INVESTIGADOR: Gabriela Acosta COORDINACIÓN GENERAL DEL PROYECTO: Salomón Nahmad y Abraham Nahón PERFILES INDIGENAS DE MÉXICO / SERIS DE SONORA / GABRIELA ACOSTA SERIS DE SONORA Foto 1. Isla Tiburón UBICACIÓN GEOGRÁFICA El territorio Seri está situado en la costa central del estado de Sonora, entre los 28 45 y 29 41 de latitud Norte y los 112 10 y 112 36 de longitud Oeste. Limita al Norte con la región de Puerto Libertad, y al sur con Bahía de Kino, al este con los campos agrícolas de Hermosillo y al Oeste con el Golfo de California o Mar Cortés. Las aguas patrimoniales Seris, con aproximadamente 100 Km de litorales se localizan en la parte Sur de la región septentrional del Golfo de California, y en la costa central del estado de Sonora. -

How Changing Lifestyles Impact Seri Smellscapes and Smell Language

How Changing Lifestyles Impact Seri Smellscapes and Smell Language Carolyn O’Meara, Asifa Majid Anthropological Linguistics, Volume 58, Number 2, Summer 2016, pp. 107-131 (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/anl.2016.0024 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/652276 Access provided by Max Planck Digital Library (25 Apr 2017 06:55 GMT) How Changing Lifestyles Impact Seri Smellscapes and Smell Language CAROLYN O’MEARA Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and Radboud University ASIFA MAJID Radboud University and Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics Abstract. The sense of smell has widely been viewed as inferior to the other senses. This is reflected in the lack of treatment of olfaction in ethnographies and linguistic descriptions. We present novel data from the olfactory lexicon of Seri, a language isolate of Mexico, which sheds new light onto the possibilities for olfactory terminologies. We also present the Seri smellscape, highlighting the cultural significance of odors in Seri culture that, along with the olfactory language, is now under threat as globalization takes hold and traditional ways of life are transformed. 1. Introduction. In the Seri village of El Desemboque, Sonora, Mexico, 2006, O’Meara sits chatting with some local women. The women commented how pretty my self-dyed skirt was. I thought they were interested in my skirt and wanted me to give it to them upon my departure. (I frequently brought skirts to give as presents to friends and collaborators.) In order to dissuade them from this particular skirt (which I was fond of), I tried to convey that it was stinky and dirty so they would not want it. -

FULL AUST WALK RESULTS 2006-2007.Pdf

2006 / 2007 THE RACEWALKING YEAR IN REVIEW COMPLETE VICTORIAN RESULTS MAJOR AUSTRALIAN AND MAJOR INTERNATIONAL RESULTS Tim Erickson 25 February 2010 1 Table of Contents INTERNATIONAL RESULTS ASIAN GAMES RACEWALKS, THURSDAY 7 DECEMBER 2006 ................................................................................ 4 AUSTRALIAN YOUTH OLYMPIC FESTIVAL, SYDNEY, 17-21 JAN 2007 ................................................................. 5 IAAF RACE WALKING CHALLENGE, ROUND 1, NAUCALPAN, MEXICO, SATURDAY 10 MARCH 12007 ....... 6 IAAF RACE WALKING CHALLENGE, SHENZHEN, CHINA, 24-25 MARCH 2007 ................................................... 8 26TH DUDINCE 50 KM WALKING CARNIVAL, SLOVAKIA, SATURDAY 24 MARCH 2007 ............................... 10 IAAF RACEWALKING GRAND PRIX, RIO MAIOR, PORTUGAL, SATURDAY 14 APRIL 2007 ........................... 12 7TH EUROPEAN CUP RACE WALKING, ROYAL LEAMINGTON SPA, SUNDAY 20 MAY 2007 .......................... 13 IAAF RACE WALKING CHALLENGE, LA CORUNA, SPAIN, 2 JUNE 2007 ............................................................ 17 RUSSIAN RACEWALKING CHAMPIONSHIPS, CHEBOKSARY, RUSSIA, SUNDAY 17 JUNE 2007 ................... 19 2007 IAAF RACEWALKING GRAND PRIX, KRAKOW, POLAND, JUNE 23, 2007 ................................................. 20 5TH WORLD YOUTH CHAMPIONSHIPS, OSTRAVA, CZECH REPUBLIC, 11-15 JULY 2007 .............................. 22 6TH EUROPEAN UNDER 23 CHAMPIONSHIPS, DEBRECEN, HUNGARY, 12-15 JULY 2007 ............................ 24 EUROPEAN JUNIOR CHAMPIONSHIPS, HENGELO, THE NETHERLANDS,