Download Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Pa Erns of Legislative Collaboration In

Network Paerns of Legislative Collaboration in Twenty Parliaments Franc¸ois Briae [email protected] Supplementary online material is appendix contains detailed information on the data and networks briey documented in the short note “Network Paerns of Legislative Collaboration in Twenty Parliaments”. Section A starts by reviewing the existing literature on legislative cosponsorship as a strategic position-taking device for legis- lators within parliamentary chambers. Section B then documents the data collection process, Section C summarises its results, and Section D contains the full list of party abbreviations used in the data. Section E fully documents how the cosponsorship networks were constructed and weighted, and lists some derived measures. e replication material for this study is available at https://github.com/ briatte/parlnet. e code was wrien in R (R Core Team, 2015), and the cur- rent release of the repository is version 2.6. See the README le of the reposi- tory for detailed replication instructions including package dependencies. e raw data up to January 2016 are available at doi:10.5281/zenodo.44440. CONTENTS A Background information on legislative cosponsorship . 2 B Sample denition and data collection . 4 B.1 Bills . 4 B.2 Sponsors . 10 C Descriptive statistics by country, chamber and legislature . 11 D Party abbreviations and Le/Right scores . 17 E Cosponsorship network construction . 27 E.1 Edge weights . 28 E.2 Network objects . 30 E.3 Network descriptors . 31 References . 35 1 A. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON LEGISLATIVE COSPONSORSHIP Legislative scholarship oers a wealth of studies that stress the importance of collabo- ration between Members of Parliament (MPs) in the lawmaking process. -

The Future of European Liberalism

FEATURE THE FUTURE OF EUROPEAN LIBERALISM Multi-party European parliaments provide a place for distinctively liberal parties, writes Charles Richardson he most fundamental feature of ways: our parties support the electoral system that Australian politics is the two-party supports them. system. Almost a hundred years ago, But Australia is relatively unusual in these in the Fusion of 1909, our different respects. In most European democracies, with non-Labor parties merged to create different histories and different electoral systems, Ta single party, of which today’s Liberal Party is the liberal parties survived through the twentieth direct descendant. It and the Labor Party have century, and many of them are now enjoying contended for power ever since. something of a resurgence. Before Fusion, the party system was more A brief digression here might clarify what I fl exible and different varieties of liberals had some mean by ‘liberal’. Philosophically, a liberal is one scope to develop separate identities. At the federal who believes in the tenets of the Enlightenment, level, there were Free Trade and Protectionist a follower of Montesquieu, Smith and von parties; in most of the states, there were Liberal and Humboldt. Applying the word to political parties Conservative parties. Sometimes rival liberal groups I am not using it as a philosophical term of art, were allied with each other or with conservatives, but as a practical thing: the typical liberal parties but sometimes they joined with Labor: George are those that have a historical connection with Reid, the Free Trade premier of New South Wales, the original liberal movements of the nineteenth for example, governed with Labor support for most century, with their programme of representative of the 1890s. -

Codebook CPDS I 1960-2013

1 Codebook: Comparative Political Data Set, 1960-2013 Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET 1960-2013 Klaus Armingeon, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2013 (CPDS) is a collection of political and institu- tional data which have been assembled in the context of the research projects “Die Hand- lungsspielräume des Nationalstaates” and “Critical junctures. An international comparison” directed by Klaus Armingeon and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member coun- tries for the period of 1960 to 2013. In all countries, political data were collected only for the democratic periods.1 The data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time- series analyses. The present data set combines and replaces the earlier versions “Comparative Political Data Set I” (data for 23 OECD countries from 1960 onwards) and the “Comparative Political Data Set III” (data for 36 OECD and/or EU member states from 1990 onwards). A variable has been added to identify former CPDS I countries. For additional detailed information on the composition of government in the 36 countries, please consult the “Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Com- position 1960-2013”, available on the CPDS website. The Comparative Political Data Set contains some additional demographic, socio- and eco- nomic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD, Eurostat or AMECO. -

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019 Codebook: SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2019 Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the 23 countries formerly included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1966 for Malta, in 1976 for Cyprus, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The government variables in the main Comparative Political Data Set are based upon the data presented in this supplement. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann. 2021. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2019. Zurich: Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich. These (former) assistants have made major contributions to the dataset, without which CPDS would not exist. In chronological and descending order: Angela Odermatt, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, Sarah Engler, David Weisstanner, Panajotis Potolidis, Marlène Gerber, Philipp Leimgruber, Michelle Beyeler, and Sarah Menegal. -

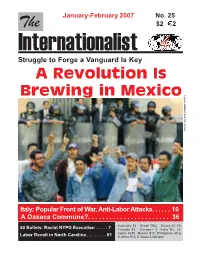

Internationalist Struggle to Forge a Vanguard Is Key a Revolution Is

January-February 2007 No. 25 The $2 2 Internationalist Struggle to Forge a Vanguard Is Key A Revolution Is Brewing in Mexico Times Addario/New Lynsey York Italy: Popular Front of War, Anti-Labor Attacks. 10 A Oaxaca Commune?. 36 Australia $4, Brazil R$3, Britain £1.50, 50 Bullets: Racist NYPD Execution . 7 Canada $3, Europe 2, India Rs. 25, Japan ¥250, Mexico $10, Philippines 30 p, Labor Revolt in North Carolina . 61 S. Africa R10, S. Korea 2,000 won 2 The Internationalist January-February 2007 In this issue... Mexico: The UNAM A Revolution Is Brewing in Mexico .......... 3 Strike and the Fight for Workers 50 Bullets: Racist NYPD Cop Execution, Revolution Again ........................................................ 7 March 2000 US$3 Mobilize Workers Power to Free Mumia For almost a year, tens of Abu-Jamal! .....................'--························ 9 thousands of students occupied the largest university Italy: Popular Front of Imperialist in Latin America, facing War and Anti-Labor Attacks .................... 10 repression by both the PAI government and the PAD Break Calderon's "Firm Hand" With opposition. This 64-page special supplement tells the Workers Struggle .................................. 15 story of the strike and documents the intervention State of Siege in Oaxaca, Preparations of the Grupo in Mexico City ....................................... 17 lnternacionalista. November 25 in Oaxaca: Order from/make checks payable to: Mundial Publications, Box 3321, Church Street Station, NewYork, New York 10008, U.S.A. Night of the Hyenas .............................. 20 Oaxaca Is Burning: Showdown in Mexico ........................... 21 Visit the League for the Fourth International/ Internationalist Group on the Internet The Battle of Oaxaca University ............. 23 http://www.internationalist.org A Oaxaca Commune? ..................... -

Codebook CPDS III 1990-2012

Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET III 1990-2012 Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012 is a collection of political and institutional data. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for a group of 36 OECD and/or EU- member countries for the period 1990-20121. The data are primarily from the data set created at the University of Berne, Institute of Political Science and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation: The Comparative Political Data Set I (CPDS I). However, the present data set differs in several aspects from the CPDS I dataset. Compared to CPDS I Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus (Greek part), Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia have been added. The present data set is suited for cross-national, longitudinal and pooled time series analyses. The data set contains some additional demographic, socio- and economic variables. However, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD. For trade union membership, excellent data for European trade unions is provided by Jelle Visser (2013). When using the data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. This data set is to be cited as: Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler. 2014. Comparative Political Data Set III 1990-2012. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2014-09-30 1 Data for former communist countries begin in 1990 for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Hungary, Malta, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Lativa and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. -

Appendix 1A: List of Government Parties September 12, 2016

Updating the Party Government data set‡ Public Release Version 2.0 Appendix 1a: List of Government Parties September 12, 2016 Katsunori Seki§ Laron K. Williams¶ ‡If you use this data set, please cite: Seki, Katsunori and Laron K. Williams. 2014. “Updating the Party Government Data Set.” Electoral Studies. 34: 270–279. §Collaborative Research Center SFB 884, University of Mannheim; [email protected] ¶Department of Political Science, University of Missouri; [email protected] List of Government Parties Notes: This appendix presents the list of government parties that appear in “Data Set 1: Governments.” Since the purpose of this appendix is to list parties that were in government, no information is provided for parties that have never been in government in our sample (i.e, opposition parties). This is an updated and revised list of government parties and their ideological position that were first provided by WKB (2011). Therefore, countries that did not appear in WKB (2011) have no list of government parties in this update. Those countries include Bangladesh, Botswana, Czechoslovakia, Guyana, Jamaica, Namibia, Pakistan, South Africa, and Sri Lanka. For some countries in which new parties are frequently formed and/or political parties are frequently dissolved, we noted the year (and month) in which a political party was established. Note that this was done in order to facilitate our data collection, and therefore that information is not comprehensive. 2 Australia List of Governing Parties Australian Labor Party ALP Country Party -

Codebook the Partisan Composition of Governments Database (PACOGOV)

Codebook The Partisan Composition of Governments Database (PACOGOV) Content Version ........................................................................................................................................................... - 1 - Citation .......................................................................................................................................................... - 1 - Variable names .............................................................................................................................................. - 1 - Classification of the parties into party families ............................................................................................. - 2 - Calculation of cabinet seat shares ................................................................................................................. - 3 - Calculation of the number of ministers in the government (“ncab”) ........................................................... - 3 - Country coverage .......................................................................................................................................... - 3 - Classification of parties by country ............................................................................................................... - 4 - Main Sources ............................................................................................................................................... - 12 - Contact ....................................................................................................................................................... -

List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2015a from May 22, 2015 Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset Version 2015a 1 Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the party’s or alliance’s name in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list by themselves. If the composition of an alliance changed between different elections, this change is covered as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party was a split from another party or a merger of a number of other parties and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 1.1 Albania ID Covering Abbrev Parties No. -

Codebook: Government Composition 1960-2012 Codebook SUPPLEMENT to the COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION

Codebook: Government Composition 1960-2012 Codebook SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2012 Klaus Armingeon, David Weisstanner and Laura Knöpfel The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the countries included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Hungary, Malta, Romania and Slovakia, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The Comparative Political Data Set I and Comparative Political Data Set III government variables are based upon the data presented in this supplement. In any work using the date from this data set, please cite both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote as: Klaus Armingeon, David Weisstanner and Laura Knöpfel. 2014. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2012. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2014-09-30 1 Codebook: Government Composition 1960-2012 CONTENTS 1. General variables ............................................................................................................ 2 -

Government Composition, 1960-2014 Codebook

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2014 Codebook: SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2014 Klaus Armingeon, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel and David Weisstanner The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the 23 countries formerly included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1966 for Malta, in 1976 for Cyprus, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The government variables in the main Comparative Political Data Set are based upon the data presented in this supplement. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Christian Isler, David Weisstanner and Laura Knöpfel. 2016. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2014. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne. Last updated: 2016-08-22 1 Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2014 CONTENTS 1. General variables ........................................................................................................... -

CSESII Parties and Leaders Original CSES Text Plus CCNER Additions (Highlighted)

CSESII Parties and Leaders Original CSES text plus CCNER additions (highlighted) =========================================================================== ))) APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS =========================================================================== | NOTES: PARTIES AND LEADERS | | This appendix identifies parties active during a polity's | election and (where available) their leaders. | | Provided are the party labels for the codes used in the micro | data variables. Parties A through F are the six most popular | parties, listed in descending order according to their share of | the popular vote in the "lowest" level election held (i.e., | wherever possible, the first segment of the lower house). | | Note that in countries represented with more than a single | election study the order of parties may change between the two | elections. | | Leaders A through F are the corresponding party leaders or | presidential candidates referred to in the micro data items. | This appendix reports these names and party affiliations. | | Parties G, H, and I are supplemental parties and leaders | voluntarily provided by some election studies. However, these | are in no particular order. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- >>> PARTIES AND LEADERS: ALBANIA (2005) --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 02. Party A PD Democratic Party Sali Berisha 01. Party B PS Socialist Party Fatos Nano 04. Party C PR Republican Party Fatmir Mediu 05. Party D PSD Social Democratic Party Skender Gjinushi 03. Party E LSI Socialist Movement for Integration Ilir Meta 10. Party F PDR New Democratic Party Genc Pollo 09. Party G PAA Agrarian Party Lufter Xhuveli 08. Party H PAD Democratic Alliance Party Neritan Ceka 07. Party I PDK Christian Democratic Party Nikolle Lesi 06. LZhK Movement of Leka Zogu I Leka Zogu 11. PBDNj Human Rights Union Party 12. Union for Victory (Partia Demokratike+ PR+PLL+PBK+PBL) 89.