Chaturvedi, Rohini. the Need for Creating Policy Spaces in Joint Forest Management: a Case Study from the Punjab-Shiwaliks, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

014 5891Ny0504 88 93

New York Science Journal 2012;5(7) http://www.sciencepub.net/newyork Estimation of Area under Winter Vegetables in Punjab Districts: through Remote Sensing & GIS Technology 1 Singh Avtar, 2 Khanduri Kamlesh 1 Technical Associate, JRF,Forest Survey of India(FSI),Dehradun,India 2D.Phil Research Scholar,Dpt. of Geography,HNBGU,JRF(FSI), Uttrakhand,India [email protected] Abstract: The Study area consists of five northern districts (ex.Gurdaspur) of Punjab State, namely, Amritsar, Tarn Taran, Kapurthala, Jalandhar and Hoshiarpur. In this study, Acreage Estimation of Vegetables in northern Punjab is carried out by using Multidate IRS - P6 AWiFS Data sets of seven dates viz., September (30), October (14, 24), November (17), December (25), January (4, 13). The aim of this study is to detect area estimation under winter vegetables in Punjab districts between 2005 - 2008 using satellite images. Vegetable area carried out by decision rule based classification: two models are created, one for acreage estimation of vegetables the other for generation of NDVI of all date satellite data. After classification of the image, classified image is recoded to merge different classes of the single output category in one category. Winter Vegetables have been detected by image processing method in EDRAS imagine9.3, ArcGIS9.3. In study area, as a whole there is positive change (14.9%) in area under vegetable crop. But two districts, namely, Kapurthala and Jalandhar have experienced negative change .But in another three districts Amritsar, Tarn Taran and Hoshiarpur districts have recorded positive change in area under vegetable. [Singh Avtar, Khanduri Kamlesh. Estimation of Area under Winter Vegetables in Punjab Districts: through Remote Sensing & GIS Technology. -

State Profiles of Punjab

State Profile Ground Water Scenario of Punjab Area (Sq.km) 50,362 Rainfall (mm) 780 Total Districts / Blocks 22 Districts Hydrogeology The Punjab State is mainly underlain by Quaternary alluvium of considerable thickness, which abuts against the rocks of Siwalik system towards North-East. The alluvial deposits in general act as a single ground water body except locally as buried channels. Sufficient thickness of saturated permeable granular horizons occurs in the flood plains of rivers which are capable of sustaining heavy duty tubewells. Dynamic Ground Water Resources (2011) Annual Replenishable Ground water Resource 22.53 BCM Net Annual Ground Water Availability 20.32 BCM Annual Ground Water Draft 34.88 BCM Stage of Ground Water Development 172 % Ground Water Development & Management Over Exploited 110 Blocks Critical 4 Blocks Semi- critical 2 Blocks Artificial Recharge to Ground Water (AR) . Area identified for AR: 43340 sq km . Volume of water to be harnessed: 1201 MCM . Volume of water to be harnessed through RTRWH:187 MCM . Feasible AR structures: Recharge shaft – 79839 Check Dams - 85 RTRWH (H) – 300000 RTRWH (G& I) - 75000 Ground Water Quality Problems Contaminants Districts affected (in part) Salinity (EC > 3000µS/cm at 250C) Bhatinda, Ferozepur, Faridkot, Muktsar, Mansa Fluoride (>1.5mg/l) Bathinda, Faridkot, Ferozepur, Mansa, Muktsar and Ropar Arsenic (above 0.05mg/l) Amritsar, Tarantaran, Kapurthala, Ropar, Mansa Iron (>1.0mg/l) Amritsar, Bhatinda, Gurdaspur, Hoshiarpur, Jallandhar, Kapurthala, Ludhiana, Mansa, Nawanshahr, -

![UPDATED AS ON] February 24, 2014](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8128/updated-as-on-february-24-2014-308128.webp)

UPDATED AS ON] February 24, 2014

[UPDATED AS ON] February 24, 2014 About the District Hoshiarpur district is located in the north-eastern part of the state. It falls in the Jalandhar Revenue Division and is surrounded by Kangra and Una districts of Himachal Pardesh in the north east, Jalandhar and Kapurthala districts (interspersed) in south-west and Gurdaspur district in the north-west. Recent excavations have revealed that Hoshiarpur district was a part of Indus Valley civilization. Legends also say that several places in the district were associated with “Pandavas” in the epic Mahabharata. Today, Hoshiarpur has a prominent position on the agricultural map of the country. The district has several small and medium scale industries which have provided employment opportunities to the local mass. Hoshiarpur is famous for its fruit gardens and wooden toys as well as inlay work of hathi dant (ivory). Archaeology Museum, Sadhu Ashram and Dholbaha are places worth seeing in a radius of 25 Kms. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS COURT HOSHIARPUR Page 1 [UPDATED AS ON] February 24, 2014 Facts & Figures Area 3365sq. Km Area under forests 201 Latitude between 30° -9' and32°-5' North Longitude between 75° -32'and 76° -12' East Population (2001) 14, 78,045 Males 7, 63,753 Females 7, 14,292 PopulationDensity 439 per sq. km SexRatio 935 No. of Sub Divisions 4 No. of Tehsils 4 No. of sub-Tehsils 5 Blocks 10 No. of Villages 1,426 PostalCode 146001 STDCode 01882 Averagerainfall 1125 mm DISTRICT AND SESSIONS COURT HOSHIARPUR Page 2 [UPDATED AS ON] February 24, 2014 How to reach Hoshiarpur can be better approached by road. -

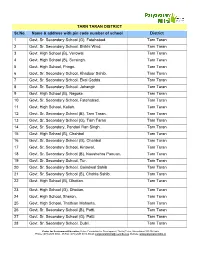

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Militancy and Media: a Case Study of Indian Punjab

Militancy and Media: A case study of Indian Punjab Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab for the award of Master of Philosophy in Centre for South and Central Asian Studies By Dinesh Bassi Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. V.J Varghese Administrative Supervisor: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab, Bathinda 2012 June DECLARATION I declare that the dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. V. J. Varghese, Assistant Professor, Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, and administrative supervision of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, Dean, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Dinesh Bassi) Centre for South and Central Asian Studies School of Global Relations Central University of Punjab Bathinda-151001 Punjab, India Date: 5th June, 2012 ii CERTIFICATE We certify that Dinesh Bassi has prepared his dissertation entitled MILITANCY AND MEDIA: A CASE STUDY OF INDIAN PUNJAB for the award of M.Phil. Degree under our supervision. He has carried out this work at the Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. V. J. Varghese) Assistant Professor Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. (Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana) Dean Centre for South and Central Asian Studies, School of Global Relations, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. -

Changing Caste Relations and Emerging Contestations in Punjab

CHANGING CASTE RELATIONS AND EMERGING CONTESTATIONS IN PUNJAB PARAMJIT S. JUDGE When scholars and political leaders characterised Indian society as unity in diversity, there were simultaneous efforts in imagining India as a civilisational unity also. The consequences of this ‘imagination’ are before us in the form of the emergence of religious nationalism that ultimately culminated into the partition of the country. Why have I started my discussion with the issue of religious nationalism and partition? The reason is simple. Once we assume that a society like India could be characterised in terms of one caste hierarchical system, we are essentially constructing the discourse of dominant Hindu civilisational unity. Unlike class and gender hierarchies which are exist on economic and sexual bases respectively, all castes cannot be aggregated and arranged in hierarchy along one axis. Any attempt at doing so would amount to the construction of India as essentially the Hindu India. Added to this issue is the second dimension of hierarchy, which could be seen by separating Varna from caste. Srinivas (1977) points out that Varna is fixed, whereas caste is dynamic. Numerous castes comprise each Varna, the exception to which is the Brahmin caste whose caste differences remain within the caste and are unknown to others. We hardly know how to distinguish among different castes of Brahmins, because there is complete absence of knowledge about various castes among them. On the other hand, there is detailed information available about all the scheduled castes and backward classes. In other words, knowledge about castes and their place in the stratification system is pre- determined by the enumerating agency. -

A Minority Became a Majority in the Punjab Impact Factor: 8

International Journal of Applied Research 2021; 7(5): 94-99 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 A minority became a majority in the Punjab Impact Factor: 8. 4 IJAR 2021; 7(5): 94-99 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 17-03-2021 Dr. Sukhjit Kaur Accepted: 19-04-2021 Abstract Dr. Sukhjit Kaur This study will focus on the Punjabi Suba Movement in Punjab 1966. The Punjabi Suba came into Assistant Professor, being after various sacrifices and struggles. The Indian Government appointed ‘Shah Commission’ to Department of History, Guru demarcate the boundaries of Punjab and Haryana. The reorganization bill was passed on the basis of Nanak College, Budhlada, recommendations of this committee only. Punjab was divided into two states; Punjabi Suba and Punjab, India Haryana under Punjab Reorganization Act, 1966. Certain areas of undivided Punjab were given to Himachal Pradesh. However, Haryana was raised as a rival to the state of Punjabi language (which was to be made for Punjab). Common links had been made for Punjab and Haryana. Haryana was the area of Hindi-speakers. It could have been easily amalgamated with neighboring Hindi states of Rajasthan and U.P. But, the state of Punjab, which was demanding the areas of Punjabi –speakers, was crippled and made lame as well. Such seeds were sown for its future of economic growth that would not let it move forward. Haryana welcomed the Act of reorganization. As a result, the common forums were removed for Haryana and Punjab and Sant Fateh Singh and the Akali Dal welcomed this decision. Methodology: The study of this plan of action is mainly based on the available main material content. -

International Journal of Education and Science Research Review

International Journal of Education and Science Research Review P-ISSN 2349-1817, E- ISSN 2348-6457 www.ijesrr.org June- 2017, Volume-4, Issue-3 Email- [email protected] LINGUISTIC REORGANIZATION OF STATES: IMPACT ON PUNJAB AND HARYANA Dr. SURENDER SINGH Assistant Professor Department of Political Science R.K.S.D. (PG) College, Kaithal (HR) INTRODUCTION India became free from British with the passing of independence Act 1947, this act divided country in to two independent states India and Pakistan. However, criteria about princely state act lay down under section 7(1) (B). After the transfer of powers to Indian hands some of the princely states demanded their independence under section 7(1) (B) and refused to unite to India. This act of princely states was not acceptable to the congress leaders. Out of 562, 556 princely states decided to join with Indian Union on the pretext their interest will be safe in the Indian union. Three states like Junagarh, Hyderabad and Jammu and Kashmir, opted to remain independent. Junagarh join the Indian Union after plebiscite, whereas Hyderabad forced to join the Indian Union. Third princely state of Jammu and Kashmir joined the Indian Union after a treaty between Maharaja Hari Singh and Jawaharlal Nehru, when it was attack by Pakistani guerrillas. The accession of the state to the Indian Union was partial solution to the problem as these states joined India only to three matters of defence, external affairs and communication. The new look of India after independence merged 216 states designated as part (A) states, 275 states designated as part (B) states and 6 states categories as (C) states. -

A Survey Report on Groundwater Contamination of Doaba Belt of Punjab Due to Heavy Metal Arsenic

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2018): 7.426 A Survey Report on Groundwater Contamination of Doaba Belt of Punjab due to Heavy Metal Arsenic Hardev Singh Virk Professor of Eminence, Punjabi University, Patiala, Punjab, India Abstract: Punjab is facing a crisis situation due to high levels of heavy metals in underground water table of Punjab. ICAR has reported arsenic beyond safe limit in 13 districts of Punjab. According to PWSSD report submitted to World Bank in 2018, there are 2989 habitations out of 15060 surveyed in Punjab, which fall under quality affected (QA) category (25% nearly). In this survey report, groundwater quality data pertaining to Arsenic is reported in the districts of Hoshiarpur and Kapurthala of the Doaba belt of Punjab. The occurrence of high Arsenic in groundwater is of geogenic origin and may be attributed to the river basins in Punjab. Methods for Arsenic removal and its health hazard effects are briefly discussed. Keywords: Groundwater, Arsenic, Acceptable limit, AMRIT, Health hazards, Punjab 1. Introduction contamination in its sophisticated laboratory set up in Mohali (Punjab), using state of art instrumentation including Arsenic (As) is a toxic element classified as a human ICPMS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) carcinogen that contributes to cancers of both skin and and Ion Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (IC-MS). internal organs (liver, bladder, kidney and intestinal) [1]. PWSSD has prepared a comprehensive report on Water Arsenic was detected in groundwater for the first time in the Quality Monitoring and Mitigation Strategy for the Punjab early 1990s in Bangladesh and West Bengal of India. -

The Babbar Akalis of Hoshiarpur Ms

The Babbar Akalis of Hoshiarpur Ms. Gurinder Kaur (Research Scholar) S.B.B.S. University, Khiala (Jalandhar) Ph. 9915072042 E.Mail: [email protected] Abstract: In India’s struggle for independence, the freedom fighters of Hoshiarpur played a very significant role. The Hoshiarpur district was a hub of Ghadarities and Babbar Akalis. The Babbar Akalis in Punjab emerge basically as a reaction to the Nankana Sahib Tragedy. The present study details the origin of Babbbar Akalis and the extent of their activities in the Hoshiarpur district. The idea of Babbar Akali Movement emerged from the deliberation of Sikh Education Conference held on 19th to 21st of March 1921 A.D. at Hoshiarpur. The Chakarvarti Jatha was organised at Rurka Kalan by Kishan Sigh Gargajj. Later on Babbar Akali evolved from the Chakarvarti Jatha in 1922 A.D. The Babbar Akali mainly eliminated the sycophants (jholi-chuks) of the Britsh Government. It is interesting to note the participation of women in this movement. This study also gives information on the Babbar Akali conspiracy trial cases. The convictions and sentences of the Babbar Akalis are given in the table no. 1 and 2. Keywords: Babbar Akali, Women, Independence, Significant role, Chakarvarti Jatha, Sycophants (Jholi-Chuks). In the middle of 19th century and in the opening decades of the 20th century many revolutionary Movements in Punjab were engaged in India’s struggle for freedom. The first important movement in Punjab was the Namdhari movement, which was founded by Baba Balak Singh in 1857. At very outset the aim of Namdhari movement was socio-religious reforms, but subsequently it turned rebellious and came into direct confrontation with British during the time period of Bhai Maharaj Singh (Nihal Singh).1 The next freedom movement was the Ghadar Movement. -

Hoshiarpur District, Punjab

क� द्र�यू�म भ जल बोड셍 जल संसाधन, नद� �वकास और गंगा संर�ण मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India Report on AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN Hoshiarpur District, Punjab उ�र� पि�चम �ेत्र, चंडीगढ़ North Western Region, Chandigarh AQUIFER MAPPING & MANAGEMENT PLAN HOSHIARPUR DISTRICT PUNJAB Centralntral Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resouesources, River Development and Gangaa RejRejuvenation Government of India 2018 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. DATA COLLECTION AND GENERATION 3. HYDROGEOLOGY 4. GROUND WATER RESOURCES 5. GROUND WATER ISSUES 6. AQUIFER MANAGEMENT PLAN 7. BLOCKWISE AQUIFER MAPS AND MANAGEMENT PLAN i. BHUNGA BLOCK ii. DASUYA BLOCK iii. GARHSHANKAR BLOCK iv. HAZIPUR BLOCK v. HOSHIARPUR -I BLOCK vi. HOSHIARPUR -II BLOCK vii. MAHILPUR BLOCK viii. MUKERIAN BLOCK ix. TALWARA BLOCK x. TANDA BLOCK 8. CONCLUSION LIST OF FIGURES Fig 1: Base Map of Hoshiarpur District. Fig 2: Location of CGWB, PSTC, WRED, Private Wells. Fig 3: Validated Exploration Data of Hoshiarpur District. Fig 4: Elevation Contour Map-Hoshiarpur District. Fig 5: 3Dimension Lithological Model-Hoshiarpur District. Fig 6: 3Dimension Lithological Fence of Hoshiarpur District. Fig 7: 3Dimension Aquifer model - Hoshiarpur District. Fig 8: Cross sections of Aquifer Map of Hoshiarpur District. Fig 9: Methodology for Resource Estimation in Unconfined and Confined Aquifer System. Fig 10: Irrigation tube wells as per depth. Fig 11: Ground water trend versus rainfall. Fig 12: Long term ground water table variation. Fig 13: Irrigation tube wells as per depth. LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Data availability of exploration wells in Hoshiarpur district. -

Epidemics in Colonial Punjab Sasha Tandon

217 Sasha Tandon: Epidemics in Punjab Epidemics in Colonial Punjab Sasha Tandon Panjab University, Chandigarh _______________________________________________________________ The Punjab region was one of the worst affected from the epidemics of malaria, smallpox, cholera and the plague, which broke out recurrently from 1850 to 1947 and caused widespread mortality. The paper discusses the outbreak and pattern of epidemics as well as their handling by the colonial state which used unprecedented measures because of the military and economic importance of the region. However, its measures remained haphazard and tentative due to the lack of knowledge about the causes of the diseases till then. The outbreak of the plague during the closing years of the nineteenth century brought about an alarmist response from the British who tried to deal with it comprehensively, often using coercion. The effects of the epidemics and people’s responses varied in rural and urban areas. While the urban middle classes generally collaborated with the government, people in villages and small towns resisted the government measures in different ways, thus shedding their generally docile attitude towards the administration. _______________________________________________________________ Epidemics of malaria, cholera, smallpox and the plague broke out intermittently and recurrently, with varied intensity in different areas of colonial Punjab. Initially, the colonial medical opinion ascribed the epidemics to the habits and customs of the natives and geographical variations, overlooking, thus, the actual causal agents and environmental factors, particularly those created by the colonial policies and measures. Consequently, the measures adopted to combat the epidemics remained haphazard and tentative. The people looked at the government with suspicion and showed reluctance to adopt them.