Acta Comeniana 24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Elias Artista Redivivus, Oder, Das Buch Vom Salz Und Raum

U Elias Artista reäivivu8 oder Das Ruch vom Salz und Raum Von Dr. ?er<ttnRn6 WaacK Mit Abbildungen ZSZ3 Im Verlage von Nermsn» S»r8äork in Serlin 30 deeinnti»O»emderlSl2ru erscKeinen 6»sLroK«iLelekte8»mmeIverK: Lis« LammImiA 8«lteaer Aterer unö neuerer>VerKe »der ^lcKemle, ^agle, Kabbalan, Freimaurer, KosenKreu^er, ttexen, l'eukel U8w. U8^. ««»»»Legede» unter Nttvtriru»r »»mnnrter (leiokrter von «»I» entd,ltev6 6ie 6em Vnrtte»derei8cKen Prälaten ZoK.V»ient. Xnckre« ^usescKriedeoen vier Nsuptscdrirte» 6er atten kZ«senKreu?er. l. OKvmKcne ttoc»«it OKristisni lZosencreut? ^nno l4S9. Z. XUgemeine un6 Oenerai-lZekormstion 6er gsnwen Welt. >. ?am» r»terniwti8 «6er Lnt6ecKunß 6er Lru6erscnakt <Zes KocniSblicKe» Or6ens 6« Kosen-Oreutre». 4. Oonkessw ?raternit»ti» o6er Leice»ntnis 6er ISblicKen Lru6erscnskt 6es docnAeenrteu kZosen-Oreut^es, Vortgetreu n»ed aen lZrigin»l»n8L»de» von 1614— 1616. Lingeleitet unck der»usLegeden von vr. m«l» ?er6. tt»sck. Liu starker Ssn6 mit ^ddiI6uvg«n. In ?veiisrb!gem UmscdlsL mit öe» nutsung <ie» Kembrsn6tscKen rsustdilaes. Llegnnt droeeniert K4. 4.—. In OriAin»ldsnö i«. S.SO 20 numerierte Lxemplsre Ruk UoliiinS. Uen6-Sütten. SroseK. itt. 10.— ferner Klersus sl» Lin?el»usLsde: 0Kvmi8cne ttock^eit CKr!8tian! Ko8encreut2 LlegAnt br«»eniert itt. 3.—. Kl Origin»lb»nck «. 4.— 20 numerierte Exemplare suk rloilSn6. r!an6»Sütten. vroscn. d Kl. 9.— — Oer «velte cker Lsmmlung et«vs im ^»nuer I9l3 erscneinen6, vir6 von 6er tdeoretiscnen Ii»dd»I»Ii, 6er iiZ6ised»mv5tiscKen Qe» Keimienre, Ksn6eln un6 eine reicKe lZIütenlese 6er siten lZeneimnisse 6er Ksbbuiistiscden l.enre aus ,8onnr* un6 .ZeÄrnn" bringen. Oer «lrlNe »»»«I «Ir6 6ie QeKeimnisse 6er prsktiscnen liskbslnk entKMlen, 6eren Künste in 6ie »VeiKe Magie" Kinüber8pielen. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Alchemy Collection in the St

A Guide to the Ethan Allen Hitchcock Alchemy Collection in the St. Louis Mercantile Library The St. Louis Mercantile Library Association Major-General Ethan Allen Hitchcock (1798 - 1870) A GUIDE TO THE ETHAN ALLEN HITCHCOCK COLLECTION OF THE ST. LOUIS MERCANTILE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION A collective effort produced by the NEH Project Staff of the St. Louis Mercantile Library Copyright (c) 1989 St. Louis Mercantile Library Association St. Louis, Missouri TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Staff................................ i Foreword and Acknowledgments................. 1 A Guide to the Ethan Allen Hitchcock Collection. .. 6 Aoppendix. 109 NEH PROJECT STAFF Project Director: John Neal Hoover* Archivist: Ann Morris, 1987-1989 Archivist: Betsy B. Stoll, 1989 Consultant: Louisa Bowen Typist: ' Betsy B. Stoll This project was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities * Charles F. Bryan, Jr. Ph.D., Executive Director of the Mercantile Library 1986-1988; Jerrold L. Brooks, Ph.D. Executive Director of the Mercantile Library, 1989; John Neal Hoover, MA, MLS, Acting Librarian, 1988, 1989, during the period funded by NEH as Project Director -i- FOREWORD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: For over one thousand years, the field of alchemy gathered to it strands of religion, the occult, chemistry, pure sciences, astrology and magic into a broad general philosophical world view which was, quite apart from the stereotypical view of the charlatan gold maker, concerned with the forming of a basis of knowledge on all aspects of life's mysteries. As late as the early nineteenth century, when many of the modern fields of the true sciences of mind and matter were young and undeveloped, alchemy was a beacon for many people looking for a philosophical basis to the better understanding of life--to the basic religious and philosophical truths. -

Alchemy Ancient and Modern

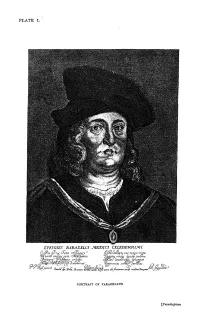

PLATE I. EFFIGIES HlPJ^SELCr JWEDlCI PORTRAIT OF PARACELSUS [Frontispiece ALCHEMY : ANCIENT AND MODERN BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ALCHEMISTIC DOC- TRINES, AND THEIR RELATIONS, TO MYSTICISM ON THE ONE HAND, AND TO RECENT DISCOVERIES IN HAND TOGETHER PHYSICAL SCIENCE ON THE OTHER ; WITH SOME PARTICULARS REGARDING THE LIVES AND TEACHINGS OF THE MOST NOTED ALCHEMISTS BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. AUTHOR OF "ON THE CALCULATION OF THERMO-CHEMICAL CONSTANTS," " MATTER, SPIRIT AND THE COSMOS," ETC, WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS SECOND AND REVISED EDITION LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LTD. 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 4 1922 First published . IQH Second Edition . , . 1922 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION IT is exceedingly gratifying to me that a second edition of this book should be called for. But still more welcome is the change in the attitude of the educated world towards the old-time alchemists and their theories which has taken place during the past few years. The theory of the origin of Alchemy put forward in I has led to considerable discussion but Chapter ; whilst this theory has met with general acceptance, some of its earlier critics took it as implying far more than is actually the case* As a result of further research my conviction of its truth has become more fully confirmed, and in my recent work entitled " Bygone Beliefs (Rider, 1920), under the title of The Quest of the Philosophers Stone," I have found it possible to adduce further evidence in this connec tion. At the same time, whilst I became increasingly convinced that the main alchemistic hypotheses were drawn from the domain of mystical theology and applied to physics and chemistry by way of analogy, it also became evident to me that the crude physiology of bygone ages and remnants of the old phallic faith formed a further and subsidiary source of alchemistic theory. -

Pdf Apologética De La Alquimia En La Corte De Felipe II. Richard

“Apologética de la… Juan Pablo Bubello APOLOGÉTICA DE LA ALQUIMIA EN LA CORTE DE FELIPE II. RICHARD STANIHURST Y SU“EL TOQUE DE ALQUIMIA” (1593) Entre diversas opiniones de diversos autores, hallo ser mas verosímil que esta palabra griega, chimia, se deribe del berbo griego cheo, q significa fundir, por quanto los chimistas son forçados muchas vezes trabajar en fundir los metales y minerales, para su mejor preparación. Y de aquí paresçe que esta arte chimica tomo el nome, a la qual palabra los arabes añadieron su articulo al, y asi, de chimia hizieron alchimia, significando ambas palabras una misma cosa. (Stanihurst, El toque de alquimia…, 1593)1 Uno de los miembros del círculo filipino, Juan de Herrera (1539-1597), poseía en su biblioteca personal al De vita coelitus comparanda de Ficino; el Heptaplus de Pico della Mirándola; Polygraphia de Tritemius; De vita longa de Paracelso; Magia naturalis de Giambattista della Porta; De umbris idearum de Giordano Bruno y Monas Hieroglyphica de John Dee.2 Y si Felipe II falleció en 1598, en un registro de los libros que el sevillano Luis de Padilla enviaba desde España a las Indias apenas un lustro después (1603), leemos: “154r: tratado de yerbas y piedra Teofrasto…, Porta, fisionomia y de yerbas, Firmicua de astrologia. … 156v: Teofrasto de plantas… 158v: lemnio de astrologia, lulio de cabalistica,... 159r: los secretos de Leonardo Fierabante. en ytaliano… 8 rs., marsilio ficino de triplici vita,… 163r: agricola de re metalica 12 rs, la practica medicinal de paracelso en latin, plantas de fusiio, 164r: poligrafia de juan tritemio 5r, lulio de alquimia en 3 reales… 165v: Theofastri Paraselsi Medicini compendium, Reymundo Lullio de secretis naturae, latin, Juanes Piçi cabalistarum dosmata, Reymundi Luli testamentum, latine en 2 r”3 1 STANIHURST, R., El toque de alquimia, en el qual se declaran los verdaderos y falsos efectos del arte, y como se conosceran las falsas practicas de los engañadores y haraneros vagamundos (1593). -

Ulrich Seelbach Ludus Lectoris

Ulrich Seelbach Ludus Lectoris Studien zum idealen Leser Johann Fischarts Inhalt Vorwort ..............................................VII Literaturverzeichnis ...................................... IX 1. Volksnaher Autor, gelehrter Leser? Einleitung .................. 1 2. Texte als Subjekte. Das Konzept der Intertextualität ............ 15 3. Die Mitarbeit des idealen Lesers. Begriffsklärungen ............. 41 3.1. Annäherungen an den Leser. Modelle .................. 41 3.2. Die Notwendigkeit alter Begriffe. Zitat und Anspielung .............................. 51 3.3. Wissen ohne Werke. Historisches Exempel, Parabel, Mythos, Fabel ................................... 76 3.4. Kanon und Katalog. Begründung einer Auswahl ........... 83 4. Fingierte Traditionalität. Die Vorreden zum Eulenspiegel reimenweis ................................ 89 Exkurs: Fremde Texte im Tylo Saxo des Johannes Nemius ....... 119 5. Das Imperium des Erzählers, die Republik des Lesers. Die Geschichtklitterung ................................... 127 5.1. Berufungen, Zitate, Anspielungen ..................... 129 5.2. Mythologische und historische Exempel, Fabeln und Parabeln .................................. 184 5.3. Die Autoren-, Titel- und Exempel-Listen ............... 203 6. Titel ohne Texte. Der Catalogus catalogorum ................ 231 7. Die Wissensbereiche der idealen Leser Fischarts .............. 267 Katalog der Berufungen, Zitate und Anspielungen in der Geschichtklitterung .............................. 289 I. Die griechischen und römischen Klassiker -

Alchemical Discourses on Nature and Creation in the Blazing World (1666)

NTU Studies in Language and Literature 57 Number 22 (Dec 2009), 57-76 Contemplation on the “World of My Own Creating”: Alchemical Discourses on Nature and Creation in The Blazing World (1666) Tien-yi Chao Assistant Professor, Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Taiwan University ABSTRACT This paper examines Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World from an alchemical perspective, with special references to passages regarding the perception of the cosmos and the creation of immaterial worlds. Even though the text is not the first work addressing the Utopian theme, it is innovative in utilising alchemical allegories to present both the author’s philosophical thoughts and the process of creative writing. In order to explore the complexity, versatility and richness of The Blazing World, my reading focuses on the Empress’s discourses on nature and the narrative surrounding her creation of worlds, while at the same time draws from early modern alchemical texts, particularly the treatises by Paracelsus and Michael Sendivogius. I argue that it is necessary for modern readers to revisit the esoteric and mystical nature of alchemical imagery, in order to develop a more profound understanding of the ways in which the Duchess of Newcastle created and refined her various imaginative worlds. Keywords : alchemy, Paracelsus, Michael Sendivogius, The One, creation, Margaret Cavendish, fiction, Utopian literature. 58 NTU Studies in Language and Literature 以煉金術觀點解讀《炫麗新世界》當中的 自然觀與創世情節 趙恬儀 國立台灣大學外國語文學系助理教授 摘 要 本論文試圖從西方煉金術的角度,解讀瑪格麗特•柯芬蒂詩的奇想故事《炫 -

Esoterismo Y Esoteristas En La Modernidad Temprana Europeo-Occidental”

UNIVERSIDAD DE BUENOS AIRES FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA SEMINARIO DE INVESTIGACION Profesor: Dr. Juan Pablo Bubello 2º cuatrimestre 2013. Programa nº: “Esoterismo y esoteristas en la modernidad temprana europeo-occidental” Fundamentación-Objetivos. Como no podría ser de otra forma en el campo de las humanidades, los especialistas en la historia del esoterismo occidental mantienen entre sí arduas discusiones. Sin embargo, también coinciden en que, entre fines del siglo XV y mediados del XVII, la magia natural, la tradición hermética, la cábala cristiana, la magia astral, la astrología, la alquimia y la alquimia rosacruz se articularon de tal forma en Europa Occidental que conformaron las principales corrientes del esoterismo del período, promoviéndose entonces el desarrollo de un entramado de prácticas y representaciones heterogéneas pero específicas. Los principales agentes culturales que caracterizaron al esoterismo de la modernidad temprana europeo-occidental fueron (entre otros): Marsilio Ficino, Giovanni Pico della Mirándola, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Guillaume Postel, Paracelso, John Dee, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella, Johann Andreas, Michael Maier, Robert Fludd y Thomas Vaughan. El presente seminario de investigación propone entonces, desde el enfoque histórico-cultural, el abordaje de uno de los problemas historiográficos centrales de la Europa Moderna, articulando el análisis del esoterismo con los diversos problemas históricos de la época que le conciernen y en el cual estos esoteristas se encuentran -

Swedenborg, Paracelsus, and the Dilute Traces

SWEDENBORG, PARACELSUS, AND THE DILUTE TRACES SWEDENBORG, PARACELSUS, AND THE DILUTE TRACES: A LYRICAL AND CRITICAL REFLECTION ON MYSTICISM, REFORM, AND THE NATURE OF INFLUENCE James Wilson* he mystic treads a lonely path. Onlookers from one side sling the Tprofane at him, those watching from the other side sling the sacred. The mystic is bespattered, caked in a mixture that permeates through all his words and deeds. Followers and detractors are lured with equal ease (or difficulty), attracted and disgusted by the claims of insight and privi- leged knowledge. Both sets are passionate and problematic. As year is plastered over year, and the grass grows green above the mystic’s grave, support might increase, but so might the original message become dis- torted or diluted. Meanwhile the detractors might fade away, train their gaze on a different mark—shooting a moving target is more rewarding. But perhaps, more worryingly for the devotees, these mockers and scoff- ers may move on because they feel the foundations have been blown asunder and leveling rubble is too much of a chore. Whatever it is that transpires—adoration, neglect, degradation, respect—it is somehow irrel- evant, for the mystic is forever a man of the elsewhere and the subjunctive, whose intended audience is never realized, but always in realization. The very tag of “mystic” is worn like armor, offering protection, deflecting criticism as misreading, but at the same time slowing the pro- tagonist down, making him cumbersome and difficult to deal with. It is probably just as hard to embrace a man adorned in plate metal as it is to punch him in the guts. -

The Hermetic Journal, Was Tragically Killed in a Car Accident in the Spri of This Year

Conten Philip Ziegler: The Rosicrucian "King of Jerusalem" ........................3 Ron Heisler Two Diagrams of D.A. Freher ............................................................ 11 The Short Confession of Khunrath. ................................................... 24 The Vision of Ben Adam ....................................................................30 The Journey of Frederick Gall ........................................................... 33 The Impact of Freemasonry on Elizabethan Literature .................... 37 Ron Heisler The Table of Emerald ......................................................................... 56 John Everard A Thanksgiving to the Great Creator of the Universe .....................59 Robert Fludd Some Hidden Sources of the Florentine Renaissance....................... 69 Graham Knight Michael Sendivogius and Christian Rosenkreutz: Thc Unexpected Possibilities ............................................................72 Rafai T. Prinke The Sevenfold Adam Kadrnon and His Sephiroth ............................99 Paul Krzok The Spine in Kabbalah .....................................................................108 Paul Krzok Towards Gnosis: Exegesis of Valle-Inclb's la ldmpara Maravillosa ........................112 Robert Lima A Letter from a Hermetic Philosopher............................................ 123 General Rainsford: An Alchemical and Rosicrucian Enthusiast ... 129 Adam McLean Some Golden Moments ...................................................................135 Nick Kollerstrom -

ARCANA SAPIENZA L’Alchimia Dalle Origini a Jung Michela Pereira Arcana Sapienza L'alchimia Dalle Origini a Jung

Michela Pereira ARCANA SAPIENZA L’alchimia dalle origini a Jung Michela Pereira Arcana sapienza L'alchimia dalle origini a Jung Carocci editore I° edizione, febbraio 2001 © copyright 2001 by Carocci editore S.p.A., Roma Finito di stampare nel febbraio 2001 per i tipi delle Arti Grafiche Editoriali Srl, Urbino ISBN 88-430-1767-5 Riproduzione vietata ai sensi di legge (art. 171 della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633) Senza regolare autorizzazione, è vietato riprodurre questo volume anche parzialmente e con qualsiasi mezzo, compresa la fotocopia, anche per uso interno o didattico. Indice Introduzione 13 1. L'origine dell’alchimia: mito e storia nella tradizione occidentale 17 1.1. L’origine dell’alchmiia 17 1.2. Il mito della perfezione 22 1.3. Figli di Ermete 26 2. Segreti della natura e segreti dell'alchimia 31 2.1. I segreti della natura 31 2.2. Preludio all’alchimia 33 2.3. Le dottrine di Ermete 37 2.4. Physikà kaì mystikà 40 3- L’Arte Sacra 47 3.1. In principio la donna 47 3.2. L’altare del sacrificio 51 3.3. Il segreto dell’angelo 55 3.4. Un’acqua divina e filosofica 59 4. 65 4.1. Passaggio ad Oriente 65 7 ARCANA SAPIENZA 4.2. Alchimisti di biblioteca 67 4.3. Il fiore della pratica 69 4.4. La fabbricazione dell’oro 72 5. Cosmologie alchemiche 79 5.1. I segreti della creazione 79 5.2. La Tabula smaragdina 82 5.3. Un congresso di alchimisti 85 5.4. La chiave della sapienza 87 6 .