(C) Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry 5 400, * Statements Nitre, Were Would Oxygen.,7 of Elaboration Its Claimed Sendivogius' Into Newton,3 Sendivogius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Alchemy Ancient and Modern

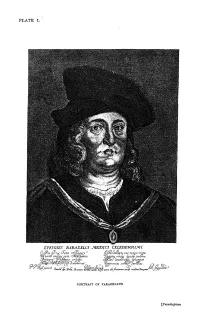

PLATE I. EFFIGIES HlPJ^SELCr JWEDlCI PORTRAIT OF PARACELSUS [Frontispiece ALCHEMY : ANCIENT AND MODERN BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ALCHEMISTIC DOC- TRINES, AND THEIR RELATIONS, TO MYSTICISM ON THE ONE HAND, AND TO RECENT DISCOVERIES IN HAND TOGETHER PHYSICAL SCIENCE ON THE OTHER ; WITH SOME PARTICULARS REGARDING THE LIVES AND TEACHINGS OF THE MOST NOTED ALCHEMISTS BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. AUTHOR OF "ON THE CALCULATION OF THERMO-CHEMICAL CONSTANTS," " MATTER, SPIRIT AND THE COSMOS," ETC, WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS SECOND AND REVISED EDITION LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LTD. 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 4 1922 First published . IQH Second Edition . , . 1922 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION IT is exceedingly gratifying to me that a second edition of this book should be called for. But still more welcome is the change in the attitude of the educated world towards the old-time alchemists and their theories which has taken place during the past few years. The theory of the origin of Alchemy put forward in I has led to considerable discussion but Chapter ; whilst this theory has met with general acceptance, some of its earlier critics took it as implying far more than is actually the case* As a result of further research my conviction of its truth has become more fully confirmed, and in my recent work entitled " Bygone Beliefs (Rider, 1920), under the title of The Quest of the Philosophers Stone," I have found it possible to adduce further evidence in this connec tion. At the same time, whilst I became increasingly convinced that the main alchemistic hypotheses were drawn from the domain of mystical theology and applied to physics and chemistry by way of analogy, it also became evident to me that the crude physiology of bygone ages and remnants of the old phallic faith formed a further and subsidiary source of alchemistic theory. -

Alchemical Discourses on Nature and Creation in the Blazing World (1666)

NTU Studies in Language and Literature 57 Number 22 (Dec 2009), 57-76 Contemplation on the “World of My Own Creating”: Alchemical Discourses on Nature and Creation in The Blazing World (1666) Tien-yi Chao Assistant Professor, Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Taiwan University ABSTRACT This paper examines Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World from an alchemical perspective, with special references to passages regarding the perception of the cosmos and the creation of immaterial worlds. Even though the text is not the first work addressing the Utopian theme, it is innovative in utilising alchemical allegories to present both the author’s philosophical thoughts and the process of creative writing. In order to explore the complexity, versatility and richness of The Blazing World, my reading focuses on the Empress’s discourses on nature and the narrative surrounding her creation of worlds, while at the same time draws from early modern alchemical texts, particularly the treatises by Paracelsus and Michael Sendivogius. I argue that it is necessary for modern readers to revisit the esoteric and mystical nature of alchemical imagery, in order to develop a more profound understanding of the ways in which the Duchess of Newcastle created and refined her various imaginative worlds. Keywords : alchemy, Paracelsus, Michael Sendivogius, The One, creation, Margaret Cavendish, fiction, Utopian literature. 58 NTU Studies in Language and Literature 以煉金術觀點解讀《炫麗新世界》當中的 自然觀與創世情節 趙恬儀 國立台灣大學外國語文學系助理教授 摘 要 本論文試圖從西方煉金術的角度,解讀瑪格麗特•柯芬蒂詩的奇想故事《炫 -

Esoterismo Y Esoteristas En La Modernidad Temprana Europeo-Occidental”

UNIVERSIDAD DE BUENOS AIRES FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA SEMINARIO DE INVESTIGACION Profesor: Dr. Juan Pablo Bubello 2º cuatrimestre 2013. Programa nº: “Esoterismo y esoteristas en la modernidad temprana europeo-occidental” Fundamentación-Objetivos. Como no podría ser de otra forma en el campo de las humanidades, los especialistas en la historia del esoterismo occidental mantienen entre sí arduas discusiones. Sin embargo, también coinciden en que, entre fines del siglo XV y mediados del XVII, la magia natural, la tradición hermética, la cábala cristiana, la magia astral, la astrología, la alquimia y la alquimia rosacruz se articularon de tal forma en Europa Occidental que conformaron las principales corrientes del esoterismo del período, promoviéndose entonces el desarrollo de un entramado de prácticas y representaciones heterogéneas pero específicas. Los principales agentes culturales que caracterizaron al esoterismo de la modernidad temprana europeo-occidental fueron (entre otros): Marsilio Ficino, Giovanni Pico della Mirándola, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Guillaume Postel, Paracelso, John Dee, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella, Johann Andreas, Michael Maier, Robert Fludd y Thomas Vaughan. El presente seminario de investigación propone entonces, desde el enfoque histórico-cultural, el abordaje de uno de los problemas historiográficos centrales de la Europa Moderna, articulando el análisis del esoterismo con los diversos problemas históricos de la época que le conciernen y en el cual estos esoteristas se encuentran -

Acta Comeniana 24

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace Acta Comeniana 24 Archiv pro bádání o životě a díle Jana Amose Komenského XLVIII Founded 1910 by Ján Kvačala International Review of Comenius Studies and Early Modern Intellectual History Internationale Revue für Studien über J. A. Comenius und Ideengeschichte der Frühen Neuzeit FILOSOFIA– PRAHA 2010 3 ACTA COMENIANA 24 (2010) Leigh T.I. Penman (Oxford) Prophecy, Alchemy and Strategies of Dissident Communication: A 1630 Letter from the Bohemian Chiliast Paul Felgenhauer (1593–c. 1677) to the Leipzig Physician Arnold Kerner Introduction Preserved in a slim folio-sized volume in the library of the University of Leipzig is a collection of forty-six letters, written by various persons between 1618 and 1630, all addressed to the Leipzig physician Arnold Kerner (fl . 1608–c. 1631).1 This fragment of Kerner’s correspondence is an invaluable source for the study of dissident thought in the Holy Roman Empire in the early seventeenth century. The volume contains letters to Kerner from the likes of the Torgau astrologer and prophet Paul Nagel (c. 1580–1624), the Langensalza antinomian Esajas Stiefel (1566–1627), his nephew Ezechiel Meth, the Bohemian chiliast Paul Felgenhauer, and several others. These letters touch on a variety of topics, including the printing and distribution of heterodox literature, the structure and nature of inchoate networks of heterodox personalities – particularly the group sur- rounding Jakob Böhme (1575–1624) – as well as communicating important biographi- cal and autobiographical information of individual dissidents and their supporters. -

The Hermetic Journal, Was Tragically Killed in a Car Accident in the Spri of This Year

Conten Philip Ziegler: The Rosicrucian "King of Jerusalem" ........................3 Ron Heisler Two Diagrams of D.A. Freher ............................................................ 11 The Short Confession of Khunrath. ................................................... 24 The Vision of Ben Adam ....................................................................30 The Journey of Frederick Gall ........................................................... 33 The Impact of Freemasonry on Elizabethan Literature .................... 37 Ron Heisler The Table of Emerald ......................................................................... 56 John Everard A Thanksgiving to the Great Creator of the Universe .....................59 Robert Fludd Some Hidden Sources of the Florentine Renaissance....................... 69 Graham Knight Michael Sendivogius and Christian Rosenkreutz: Thc Unexpected Possibilities ............................................................72 Rafai T. Prinke The Sevenfold Adam Kadrnon and His Sephiroth ............................99 Paul Krzok The Spine in Kabbalah .....................................................................108 Paul Krzok Towards Gnosis: Exegesis of Valle-Inclb's la ldmpara Maravillosa ........................112 Robert Lima A Letter from a Hermetic Philosopher............................................ 123 General Rainsford: An Alchemical and Rosicrucian Enthusiast ... 129 Adam McLean Some Golden Moments ...................................................................135 Nick Kollerstrom -

Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy ~ a Suggestive Inquiry Into the Hermetic Mystery

Mary Anne Atwood Hermetic Philosophy and Alchemy ~ A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery with a Dissertation on the more Celebrated of the Alchemical Philosophers Part I An Exoteric View of the Progress and Theory of Alchemy Chapter I ~ A Preliminary Account of the Hermetic Philosophy, with the more Salient Points of its Public History Chapter II ~ Of the Theory of Transmutation in General, and of the First Matter Chapter III ~ The Golden Treatise of Hermes Trismegistus Concerning the Physical Secret of the Philosophers’ Stone, in Seven Sections Part II A More Esoteric Consideration of the Hermetic Art and its Mysteries Chapter I ~ Of the True Subject of the Hermetic Art and its Concealed Root. Chapter II ~ Of the Mysteries Chapter III ~ The Mysteries Continued Chapter IV ~ The Mysteries Concluded Part III Concerning the Laws and Vital Conditions of the Hermetic Experiment Chapter I ~ Of the Experimental Method and Fermentations of the Philosophic Subject According to the Paracelsian Alchemists and Some Others Chapter II ~ A Further Analysis of the Initial Principle and Its Education into Light Chapter III ~ Of the Manifestations of the Philosophic Matter Chapter IV ~ Of the Mental Requisites and Impediments Incidental to Individuals, Either as Masters or Students, in the Hermetic Art Part IV The Hermetic Practice Chapter I ~ Of the Vital Purification, Commonly Called the Gross Work Chapter II ~ Of the Philosophic or Subtle Work Chapter III ~ The Six Keys of Eudoxus Chapter IV ~ The Conclusion Appendix Part I An Exoteric View of the Progress and Theory of Alchemy Chapter I A Preliminary Account of the Hermetic Philosophy, with the more Salient Points of its Public History The Hermetic tradition opens early with the morning dawn in the eastern world. -

Alchemy and Alchemical Knowledge in Seventeenth-Century New England a Thesis Presented by Frederick Kyle Satterstrom to the Depa

Alchemy and Alchemical Knowledge in Seventeenth-Century New England A thesis presented by Frederick Kyle Satterstrom to The Department of the History of Science in partial fulfillment for an honors degree in Chemistry & Physics and History & Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2004 Abstract and Keywords Abstract By focusing on Gershom Bulkeley, John Winthrop, Jr., and other practitioners of alchemy in seventeenth-century New England, I argue that the colonies were home to a vibrant community of alchemical practitioners for whom alchemy significantly overlapped with medicine. These learned men drew from a long historical tradition of alchemical thought, both in the form of scholastic matter theory and also their contemporaries’ works. Knowledge of alchemy was transmitted from England to the colonies and back across a complex network of strong and weak personal connections. Alchemical thought pervaded the intellectual landscape of the seventeenth century, and an understanding of New England’s alchemical practitioners and their practices will fill a gap in the current history of alchemy. Keywords Alchemy Gershom Bulkeley Iatrochemistry Knowledge transmission Medicine New England Seventeenth century i Acknowledgements I owe thanks to my advisor Elly Truitt, who is at least as responsible for the existence of this work as I am; to Bill Newman, for taking the time to meet with me while in Cambridge and pointing out Gershom Bulkeley as a possible figure of study; to John Murdoch, for arranging the meeting; to the helpful staff of the Harvard University Archives; to Peter J. Knapp and the kind librarians at Watkinson Library, Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut; and to the staff of the Hartford Medical Society, for letting me use their manuscript collection and for offering me food. -

Book of Aquarius by Anonymous

THE BOOK OF AQUARIUS BY ANONYMOUS Released: March 20, 2011 Updated: August 16, 2011 The Book of Aquarius By Anonymous. This web edition created and published by Global Grey 2013. GLOBAL GREY NOTHING BUT E-BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. The Book Of Aquarius 2. Foreword 3. What Is Alchemy? 4. How Does It Work? 5. The Powers Of The Stone 6. Disbelief 7. Interpretations 8. Obscurity 9. The Secret 10. Yin-Yang 11. Cycles Of Nature 12. Metallic Generation 13. The Emerald Tablet 14. What Is It Made From? 15. The Time 16. The Heat 17. Different Methods 18. Understanding The Writings 19. Overview 20. Apparatus 21. First Part 22. Second Part 23. Black Stage 24. White Stage 25. Fermentation 26. Contradictions 27. Red Stage 28. Multiplication 29. Projection 30. Appearance 31. Everburning Lamps 32. Takwin 33. Religious References 34. Prehistory 35. History Of The Stone 36. Quotes On History 37. Timeline 38. Nicolas Flamel 39. Paracelsus 40. Rosicrucians 41. Francis Bacon 42. Robert Boyle 43. James Price 44. Fulcanelli 45. Where Did They Go? 46. Shambhala 47. Ufos 48. New World Order 49. Mythology 50. Frequency And Planes 51. Universes In Universes 52. The Alchemists' Prophecy 53. Afterword 54. Help 55. Questions And Answers 56. Bibliography 1 The Book of Aquarius By Anonymous 1. The Book Of Aquarius The purpose of this book is to release one particular secret, which has been kept hidden for the last 12,000 years. The Philosophers' Stone, Elixir of Life, Fountain of Youth, Ambrosia, Soma, Amrita, Nectar of Immortality. These are different names for the same thing. -

Introduction to Jacob Boehme

This companion will prove an invaluable resource for all those engaged in research or teaching on Jacob Boehme and his readers, as historians, philos- ophers, literary scholars or theologians. Boehme is “on the radar” of many researchers, but often avoided as there are relatively few aids to understand- ing his thought, its context and subsequent appeal. This book includes a fi ne spread of topics and specialists. Cyril O’Regan, University of Notre Dame, USA 66244-139-0FM-2pass-r02.indd244-139-0FM-2pass-r02.indd i 55/31/2013/31/2013 88:46:56:46:56 AAMM 66244-139-0FM-2pass-r02.indd244-139-0FM-2pass-r02.indd iiii 55/31/2013/31/2013 88:48:14:48:14 AAMM An Introduction to Jacob Boehme This volume brings together for the fi rst time some of the world’s leading authorities on the German mystic Jacob Boehme to illuminate his thought and its reception over four centuries for the benefi t of students and advanced scholars alike. Boehme’s theosophical works have infl uenced Western culture in profound ways since their dissemination in the early seventeenth century, and these interdisciplinary essays trace the social and cultural networks as well as the intellectual pathways involved in Boehme’s enduring impact. The chapters range from situating Boehme in the sixteenth-century Radical Reformation to discussions of his signifi cance in modern theology. They explore the major contexts for Boehme’s reception, including the Pietist movement, Russian religious thought, and Western esotericism. In addition, they focus more closely on important readers, including the religious rad- icals of the English Civil Wars and the later English Behmenists, literary fi gures such as Goethe and Blake, and great philosophers of the modern age such as Schelling and Hegel. -

Robert Child's Chemical Book List of 1641

Robert Child's Chemical Book List of 1641 WILLIAM JEROME WILSON, Office of Price Administration, Washington, D. C. 3 INTRODUCTION close of his interesting biography of Child, remarks: C. A. BROWNE1 "Few characters in our colonial annals are so multi- fariously interesting and none, I think, appeals more congenially to the modern student." N October 26, 1921, while searching among the un- The main facts of Child's career, as summarized from O published papers of John Winthrop, Jr., in the Professor Kittredge's work, are the following. He was library of the Massachusetts Historical Society in born in 1613 in Kent, England; in 1628 he entered Boston, the writer discovered a book list in small, much Cambridge University, where he obtained his A.B. abbreviated writing, that bore the Latin title, "Libri degree in 1631-32 and his A.M. degree in 1635. In chymici quos possideo." He recognized in this list May, 1635, he entered the University of Leyden as a several titles of works that were in the Winthrop collec- student of medicine; he proceeded afterward to the tion of the Society Library in New York City and there- University of Padua, where he obtained his M.D. de- fore at first concluded it was a catalog of Winthrop's gree in August, 1638. Within a year or two after his re- own chemical books. But the list was not in Winthrop's turn to England he paid a visit to the Massachusetts handwriting and it was while puzzling over this phase Bay Colony, during which period he became associated of the problem that the writer remembered having read with the younger Winthrop whom he may have met in one of Dr. -

MICHAEL SENDIVOGIUS, ROSICRUCIAN, and FATHER of STUDIES of OXYGEN

Exhibit A Michael Sendivogius _________________________________________________________________________ MICHAEL SENDIVOGIUS, ROSICRUCIAN, and FATHER OF STUDIES OF OXYGEN By Frater James A. Marples, VIIIº Life Member, Nebraska S.R.I.C.F. _________________________________________________________________________ Comparatively few people have heard the name Michael Sendivogius; yet, his contributions into the field of Oxygen, were of immense importance and the relevancy of his studies continue to this very day. He was born on the 2nd of February1566 at either Skorsko or Lukawica, Poland; and died at Cravar, Silesia, in June 1636. His parents, Jacob Sedzimir and Catherine Pielsz Rogowska were both of noble families and had a small estate near Nowy Sacz, in the Cracow district of Poland. It is reported that young Michael traveled to and studied at (or at least visited) universities at Moscow, Russia; Sweden; England; Spain; Portugal; Italy where he studied the rare works of Paracelsus in The Vatican Library; Greece {where he was instructed by a patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church}; and Constantinople (now in modern-day Turkey). At this same time he was studying philosophy, medicine, rhetoric, Geometry, astronomy, mechanics, theology, and other subjects at the Universities of Cambridge, Frankfurt, Rostock, Wittenberg, Leipzig (in 1590), back to the University of Vienna (1591), and the University in Altdorf in 1594- 95 and also Ingolstadt (both in Germany) and in Prague (in today's Czech Republic). It is notable that one of his fellow students while at Altdorf was Michael Maier, another confirmed Rosicrucian. For that time-period, Sendivogius was an exceptionally well- traveled man. Michael met up with the Polish head of heraldry, Bartlomiej Paprocki, who convinced him to change his surname to a more nobler-sounding name of Sedziwoaj (sometimes spelled Sedziwoj).