Conserving the Kuttanad Wetlands: Stakeholder Preferences of Management Alternatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda and Notes for the Regional Transport

AGENDA AND NOTES FOR THE REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY MEETING TO BE HELD ON 12.03.2018, 11.00 AM AT COLLECTORATE CONFERENCE HALL ALAPPUZHA Present : Smt. T.V. Anupama I.A.S. (District Collector and Chairperson RTA Alappuzha) Members : 1. Sri. S. Surendran I.P.S. District Police Chief, Alappuzha 2. Sri. C.K. Asoken Deputy Transport Commissioner. South Zone, Thiruvananthapuram Item No. : 01 Ref. No. : G/47041/2017/A Agenda :- To reconsider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15/9612 on the route Mannancherry – Alappuzha Railway Station via Jetty for 5 years reg. This is an adjourned item of the RTA held on 27.11.2017. Applicant :- The District Transport Ofcer, Alappuzha. Proposed Timings Mannancherry Jetty Alappuzha Railway Station A D P A D 6.02 6.27 6.42 7.26 7.01 6.46 7.37 8.02 8.17 8.58 8.33 8.18 9.13 9.38 9.53 10.38 10.13 9.58 10.46 11.11 11.26 12.24 11.59 11.44 12.41 1.06 1.21 2.49 2.24 2.09 3.02 3.27 3.42 4.46 4.21 4.06 5.19 5.44 5.59 7.05 6.40 6.25 7.14 7.39 7.54 8.48 (Halt) 8.23 8.08 Item No. : 02 Ref. No. G/54623/2017/A Agenda :- To consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of a suitable stage carriage on the route Chengannur – Pandalam via Madathumpadi – Puliyoor – Kulickanpalam - Cheriyanadu - Kollakadavu – Kizhakke Jn. -

Key Electoral Data of Kuttanad Assembly Constituency | Sample Book

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/KR-106-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5313-572-0 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 128 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency -(Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-9 Constituency -(Lok Sabha) | Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-11 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Villages by Population -

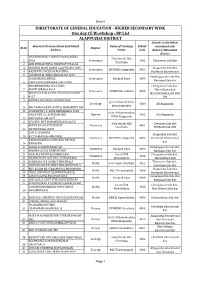

Cluster Training 2020

Sheet1 DIRECTORATE OF GENERAL EDUCATION - HIGHER SECONDARY WING One day CE Workshop - RP List ALAPPUZHA DISTRICT Schools in the below Resource Persons Name and School Name of Training School mentioned sub Sl No Subject Address Centre Code district/ Education district DILEEPKUMAR V SNHSS POOCHAKKAL Holy family HSS 1 4046 Economics 4061 Thuravoor Sub dist Cherthala 2 ANILKUMAR VJHSS NADUVATH NAGAR 3 MANJU K MANI GGHSS ALAPPUZHA 4095 Alappuzha Sub dist, Economics SDVBHSS alappuzha 4052 4 RASIYATH LMHSS ALAPPUZHA Kuttanad Educational 5 SATHYAN M GHSS MANGALAM 4019 Ambalappuzha Sub dist, SUJIKUMARI SNTHSS Economics Haripad Boys 4004 Harippad Sub dist 6 NANGIARKULANGARA ,PALLIPAD KRISHNAKUMAR K K GGHSS Chengannur Sub dist , 7 MAVELIKKARA 4013 Mavelikkara Sub Economics GBHSS Mavelikkara 4093 ANITHA G PILLAI NSS HSS KURATHIKAD dist,KAYAMKULAM SUB 8 4127 DIS 9 AMBIKA BAI,GHSS CHANDIROOR gov.mohammedans Sociology 4030 All Alappuzha ghss,alappuzha 10 BIJI DAMODARAN SNTHSS MARARIKULAM 11 VISWAJITH P S GHSS KIDANGARA 4026 Govt. Muhammedans AMAR EBY A L SAMAJAM HSS History 4012 All Alappuzha BHSS Alappuzha 12 MUTHUKULAM 4077 13 JAYAN.N SNT MARARIKULAM (4072) Holy family HSS Cherthala Sub dist BOBIN K PALIATH SFAHSS Chemistry 4061 Cherthala THURAVOOR SUB 14 ARTHUNKAL(4047) SAM R SNDPHSS Alappuzha Sub dist, 15 KUTTAMANGALAM(4035) Chemistry SDVBHSS alappuzha 4052 Kuttanad Educational RADHAKRISHNA PANICKER NSS HSS dist 16 KAVALAM 17 SANAL R GGHSS HARIPAD Ambalappuzha Sub dist, Chemistry Haripad Boys 4004 18 ANJANA GGHSS KAKKAZHAM Harippad Sub dist 19 RANI.M.S -

1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI Church, Kodukulanji Rural 5

No. LUNCH Home Sl. No Of LUNCH Parcel By Unit LUNCH Sponsored by of District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Rural / Urban Initiative Delivery No. Members (November 16 th) LSGI's (November 16 th) units (November 16 th) Near CSI church, 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 30 0 0 Kodukulanji Ruchikoottu Janakiya Coir Machine Manufacturing 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Urban 4 Janakeeya Hotel 194 0 20 Bhakshanasala Company Samrudhi janakeeya 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Pazhaveedu Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 70 0 0 bhakshanashala Community kitchen 4 Alappuzha Alappuzha South MCH junction Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 155 197 thavakkal group 5 Alappuzha Ambalppuzha North Swaruma Neerkkunnam Rural 10 Janakeeya Hotel 0 0 0 6 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 0 100 10 7 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 Janakeeya Hotel 202 0 0 8 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 55 27 0 9 Alappuzha Aroor Navaruchi Vyasa charitable trust Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 20 0 0 10 Alappuzha Aryad Anagha Catering Near Aryad Panchayat Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 7 45 0 Sasneham Janakeeya 11 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Koyickal chantha Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 172 0 0 Hotel 12 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 Janakeeya Hotel 55 0 0 13 Alappuzha Chambakulam Jyothis Near party office Rural 4 Janakeeya Hotel 81 0 0 chengannur market building 14 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM Urban 5 Janakeeya Hotel 95 0 0 complex Chennam pallipuram 15 -

An Assessment of Flood in Kuttanadu : a Study on Infrastructural Damages to Household and Coping Mechanism of the Local Self Government Institutions

A JOURNAL OF COMPOSITION THEORY ISSN : 0731-6755 An Assessment of Flood in Kuttanadu : A Study on Infrastructural Damages to Household and Coping Mechanism of the Local Self Government institutions. Sooryalekshmi.S, Guest lecturer, Sree Narayana College Varkala, Thiruvananthapuram Email : [email protected] Abstract Kerala has overcome the days of massive floods. Hard-work and money was enough to recover from all the losses occurred. At the same time, there are certain things that cannot be fixed again even if you invest your thoughts, hard work or more capital. Amongst them, Kuttanad takes a major share. All of Kerala is highly dependent on Kuttanad for their food that are yielded in a systemic and periodic method of cultivation .It is considered as the only place where in the world where rice cultivation is done up to 2 metres below the sea level. A place of this kind, is now, pushing all of the limits to recover from the disastrous flooding. So It is very important to understand the impact of floods on the life and existence of the people of Kuttanad. This study was conducted in selected panchayaths falling in Alapuzha part of Kuttanadu. Despite trying to understand the plight of the people and damages occurred, it also tries to identify the remedial strategies adopted by the local self governing bodies and the people of Kuttanad .Results suggest that Kuttanad was experienced the worst flood in the last two decades. Water level was raised to about 5 feet in the most places and 100 percentage of the surveyed household where affected to some extent. -

Ranklistnew-Staff-Nurse-Alp.Pdf

t ONLINE APPLICATION INVITED FOR STAFF NURSE (COVID .19 PREVENTION ACTITTVITIES) - RANK LrST NAME Address Rank Number Kufikad,Ponnad Aswathy R 1 Po,MannancheryAlappuzha 688538 Velichappatu Thayil,,{sramam Athira Mohan 2 Ward.Avalikunnu Po,Alappuzha Binu Bhavanam,Thannikunnu Lince George 3 P.0,Vettiyar,690534 Radha Radhika L Sadhanam,Mulavanathara,Pazhavana 4 P.0,Alaopuzha Athira babu Veliyil, Iklavoor P 0, Alpy 5 Manezhathu House Poonthoppu Ward Remya Mol K P 6 Avalookunnu PoAlappuzha Thekkepalackal HousglGnjiramchira Margarat T V 7 P.O,Mangalam Ward,Alpy,688007 Kelaparambil,Neendoor,Pallipad P 0, Daisy varghese B Alapy Ifochuvila House Kunnankeri P.O Renju R Alappuzha I Chittakkat, Kalath Ward, Avalookunnu linsha Rose Francis 10 P O, Alpy Chameth Padittathil,Panoor Pallana Rahila P.0,Thrikkunnappuzha 11 Adithyan M Kalliparambu,Pazhaveedu P O Alapy 72 Vadakkethaiyil South Aryad , West Of Anjusha M 13 Lhs Avalookunnu P.0 Alappuzha Reianimol T S Thottuchira Muhamma Po Alappuzha t4 Poonayar House,Chambakulam lomol fose 15 Po,Amicheri,Alappuzha Chirayil House,Valiyamaram Ward Saritha Chandran Po"Alappuzha 76 R[q.,e\- Modiyil House Karthika Chandran 77 ,Kurathikad,Mavelikara,6g0 107 Ethrkandathilhouse, North,Aryadu p Sushamol S O Alapy 18 Parambu Nilam Housg Aiirha Kumari T v Kadaharam,Thakazhy Alpy L9 Resmi Prasad Aikkarachem Cmc23 Cherthala 20 Di.ia S Dinesh Kunnumpurath,Muhamma p O,Alpy 2t Madavana House Pattanakad p faisy mol V O Cherthala 22 TC Suni Lawrence 5/1 94T,Chenguvilayakathveedu,Amba 23 u Saranya Satheesh Navaneeth,Pazhaveedu"Alpy 24 Aa Manzil,Kottamkulagara Shabana Shajahan Ward,Avalikunnu Po,,{ryad 25 Anjitha Raiu 'rlidhyalayam,Charamangalam,Muham maPO 26 Pilechi Nikarth, Pattanakkad p Devaprasad B o Cherthala 27 Sreebhayanam, Chithra Viswanathan Chunakkara Eas! 28 Sarath covind B po, Thoppuveli ,S L Puram 29 Palliveedu, puram. -

Kuttanad School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 46023 BBM HS Vaisyambhagom a 46024 St. Mary's HSS Champakulam a 46030 St

Kuttanad School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 46023 BBM HS Vaisyambhagom A 46024 St. Mary's HSS Champakulam A 46030 St. Mary's HS Kainakary A 46031 SNDP HS Kuttamangalam A 46032 Devamatha HS Chennamkary A 46033 DV HS Kandankary A 46042 ATG VHSS Mancompu G 46043 Govt HS Thekkekara G 46047 St. Joseph's HSS Pulimcunnu A 46056 Holy Family GHS Kainakary A 46057 NS HSS Nedumudy A 46058 Little Flower GHS Pulimcunnu A 46060 Govt HS Kuppappuram G 46201 LPS Chempumpuram G 46202 LPS Champakulam G 46203 SNDP LPS Chennamkary G 46204 LPS Kuttamangalam G 46205 LPS Mancompu G 46206 LPS Nadubhagom G 46207 NS LPS Nedumudy G 46208 LPS Ponga G 46209 Amalolbhava LPS Pulimcunnu A 46210 L F LPS Attuvathala A 46211 St. Mary's LPS Champakulam A 46212 St. Mary's LPS Kainakary A 46213 GLPS Attuvathala G 46214 LPS Vaisyambhagam G 46216 Mary Matha LPS Punnacunnam A 46217 LPS Pulimcunnu G 46218 UPS Chathurthyakary G 46219 UPS Chennamkary G 46220 UPS Kannady G 46221 UPS Nedumudy South G 46222 UPS Thottuvathala G 46223 St. Thomas UPS Champakulam A 46224 SH UPS Kannady A 46225 St. Joseph's UPS Kayalpuram A 46226 SH UPS Champakulam A 46017 Govt HS Karumady G 46062 St. Aloysius HSS Edathua A 46063 Lourde Matha HSS Pacha A 46064 MTS HS For Girls Anaprampal A 46065 St. George HSS Muttar A 46067 Govt HS Kodupunna G 46068 St. Xavier's HS Mithrakary A 46071 Govt VHSS Thalavady G 46072 CMS HS Thalavady A 46073 TMT HS Thalavady A 76075 St. -

Kuttanad Report.Pdf

Measures to Mitigate Agrarian Distress in Alappuzha and Kuttanad Wetland Ecosystem A Study Report by M. S. SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION 2007 M. S. SWAMINATHAN RESEARCH FOUNDATION FOREWORD Every calamity presents opportunities for progress provided we learn appropriate lessons from the calamity and apply effective remedies to prevent its recurrence. The Alappuzha district along with Kuttanad region has been chosen by the Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India for special consideration in view of the prevailing agrarian distress. In spite of its natural wealth, the district has a high proportion of population living in poverty. The M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation was invited by the Union Ministry of Agriculture to go into the economic and ecological problems of the Alappuzha district as well as the Kuttanad Wetland Ecosystem as a whole. The present report is the result of the study undertaken in response to the request of the Union Ministry of Agriculture. The study team was headed by Dr. S. Bala Ravi, Advisor of MSSRF with Drs. Sudha Nair, Anil Kumar and Ms. Deepa Varma as members. The Team was supported by a panel of eminent technical advisors. Recognising that the process of preparation of such reports is as important as the product, the MSSRF team held wide ranging consultations with all concerned with the economy, ecological security and livelihood security of Kuttanad wetlands. Information on the consultations held and visits made are given in the report. The report contains a malady-remedy analysis of the problems and potential solutions. The greatest challenge in dealing with multidimensional problems in our country is our inability to generate the necessary synergy and convergence among the numerous government, non-government, civil society and other agencies involved in the implementation of the programmes such as those outlined in this report. -

A Study of Disaster Caused by 2018 Kerala Flood to Kuttanad Farmers

ISSN (Online) : 2455 - 3662 SJIF Impact Factor :5.148 EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research Monthly Peer Reviewed & Indexed International Online Journal Volume: 5 Issue: 3 March 2019 Published By :EPRA Publishing CC License Volume: 5 | Issue: 3 | March 2019 || SJIF Impact Factor: 5.148 ISSN (Online): 2455-3662 EPRA International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research (IJMR) Peer Reviewed Journal A STUDY OF DISASTER CAUSED BY 2018 KERALA FLOOD TO KUTTANAD FARMERS Sony Thomas1 Aaron Joseph George2 1 Research Associate, 2Director, International Centre for Technological International Centre for Technological Innovations, Innovations, Alleppey, Alleppey, Kerala Kerala ABSTRACT Almost 90% of people in Kerala were directly or indirectly affected by the Kerala flood that took between also caused severe damages for the people in Ernakulam and Idukki districts. Almost a million people were evacuated and most numbers of people were affected in Pathanamthitta, Alappuzha, Idukki districts. Severe cases of landslides occurred in Idukki and Wayanad districts. This paper discusses the problem faced by Kuttanad 15th of August and 18th of August 2018. Over 500 people died, and many missing cases were registered. Almost 14 districts in Kerala was directly affected. In the history of Kerala, all the dams were open which farmers and also provides suggestions about how challenges faced by the Kuttanad farmers can be addressed. KEYWORDS: Kerala flood, Kuttanad 1. INTRODUCTION Kuttanad, the 'Rice Bowl of Kerala’, lies at The major occupation of people in Kuttanad the very heart of the backwaters in Alappuzha is farming. Rice is the most important agricultural district. Its wealth of paddy crops is what got it product grown there. -

C:\Users\CGO\Desktop\Final Part

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK ALAPPUZHA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory ALAPPUZHA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Nehru Trophy Boat Race Subroided with a labyrinth of backwaters, Alappuzha District is the cradle of important boat races like the Nehru Trophy Boat Race at Punnamada, Pulinkunnu Rajiv Gandhi Boat Race, and the Payippad Jalotsavam at Payippad, Thiruvanvandoor, Neerettupuram Boat Race, Champakulam Boat Race, Karuvatta and Thaikottan races. The boat races are mainly conducted at the time of ‘Onam’ festival. The Nehru Trophy Boat Race was instituted by the then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in the year 1952, on being thrilled by the enchanting beauty of the racing snake shaped boats. Ever since, the race is being conducted at the time of Onam festival on second Saturday of August every year. Various cultural programmes are also conducted along with the race, creating a festive mood in the town. Thousands of tourists from all over the world flock in, to have a glimpse at this spectacular occasion. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 141 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 23.09.2018 to 29.09.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 23.09.2018 to 29.09.2018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kannamkudichira , 24.09.2018 1168/18 U/s K N Manoj Bail from 1 Balachnadra Thirumani 19/18 Ponnattu P.O, Aroor Aroor , 18:10 hrs 279, IPC ,SI of Police Station n Mannachery P/W-2 Moonjara , 1169/18 U/s 24.09.2018 K N Manoj Bail from 2 Denson Antony 31/18 Ezhupunna P.O, Aroor 279, IPC 185 Aroor ,19:10 hrs ,SI of Police Station Ezhupunna P/W-14 of MV Act Meera Vihar, 1171/18 U/s Sukumaran 27 /18 29.09.2018 K N Manoj Bail from 3 Mithun Aroor . P O, Aroor Aroor 15 ( c) of Aroor Pillai Male ,21;10 hrs ,SI of Police Station P/W-21 KAact 29. 1171/18 U/s 27/18 Pulithara Nikarth, K N Manoj Bail from 4 Vipin Augustine Aroor 09.2018,21 15 ( c) of Aroor Yrs Aroor P/W-6 ,SI of Police Station :10 KAact 29. 24 /18 Anjattuparambil, 1173/18 U/s K N Manoj Bail from 5 Nikhil Thomas Aroor 09.2018, Aroor Yrs Aroor P/W-21 279 IPC ,SI of Police Station 20:00 26. 1175/18 U/s 28 /18 Munduparambil, K N Manoj Bail from 6 Aneesh Asokan Eramalloor 09.2018, 27 of NDPS Aroor Yrs Ezhupunna P/W-1 ,SI of Police Station 12:45 hrs Act 27. -

Alappuzha District from 18.04.2021To24.04.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 18.04.2021to24.04.2021 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Mappom thara Vijayakaumar. house, Neelamperoor 19 18-04-2021 119/2021 U/s K.K, Si of JFMC 1 Bennet Benny village, Eara KAINADI Male 14:40 279 IPC Police, Kainady RAMANKARY Neelamperoor P.S panchayath ward 5 120/2021 U/s Puthuparambil 188, 269 IPC& House, Thottakkadu Sec. 4(2)(e) (j) Vijayakaumar. Pradeep 23 Village, Vakathanam 18-04-2021 of Kerala K.K, Si of JFMC 2 Abhijith Cherukara KAINADI Kumar Male panchayath w-5, 15:25 Epidemic Police, Kainady RAMANKARY pariyaram Diseases P.S chakamchira Ordinance 2020 121/2021 U/s Kanakalil House, 188, 269 IPC Neelamperoor P.O, & Sec. 4(2)(e) Vijayakaumar. 60 Neelamperoor 18-04-2021 (j) of Kerala K.K, Si of JFMC 3 Mohan Kumar Sukumaran Neelamperoor KAINADI Male Village, 16:10 Epidemic Police, Kainady RAMANKARY Neelamperoor Diseases P.S Panchayath Ward 3 Ordinance 2020 122/2021 U/s 188, 269 IPC Idampadi Chira & Sec. Vijayakaumar. House, Neelamperoor 4(2)(e)(j) of 26 18-04-2021 K.K, Si of JFMC 4 ARUN Sivaprasad village, Valady Kerala KAINADI Male 18:10 Police, Kainady RAMANKARY Neelamperoor Epidemic P.S panchayath ward 8 Diseases Ordinance 2020 143/2021 U/s puthen 23 PULLUKULANG 18-04-2021 279 KANAKAKUN JFMC I 5 Vipin viswan parambil,nallanikkal,A santhoshkumar Male ARA 12:05 IPC,4(2)(a) & 5 NU HARIPAD rattupuzha OF KEDO 177/2021 U/s Panachikkal, 31 20-04-2021 269 IPC JFMC 6 Xavier Joy Kuthirapanthy, Poopally NEDUMUDI kurian T V SI Male 18:30 ,4(2)(f) r/w 5 RAMANKARY Alappuzha of KEDO 2020 227/2021 U/s 40 ATTUCHIRA HOUSE, 18-04-2021 JFMC 7 JOSEMON THOMAS Veliyanadu 4(2)(j) r/w.