Kuttanad Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda and Notes for the Regional Transport

AGENDA AND NOTES FOR THE REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY MEETING TO BE HELD ON 12.03.2018, 11.00 AM AT COLLECTORATE CONFERENCE HALL ALAPPUZHA Present : Smt. T.V. Anupama I.A.S. (District Collector and Chairperson RTA Alappuzha) Members : 1. Sri. S. Surendran I.P.S. District Police Chief, Alappuzha 2. Sri. C.K. Asoken Deputy Transport Commissioner. South Zone, Thiruvananthapuram Item No. : 01 Ref. No. : G/47041/2017/A Agenda :- To reconsider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15/9612 on the route Mannancherry – Alappuzha Railway Station via Jetty for 5 years reg. This is an adjourned item of the RTA held on 27.11.2017. Applicant :- The District Transport Ofcer, Alappuzha. Proposed Timings Mannancherry Jetty Alappuzha Railway Station A D P A D 6.02 6.27 6.42 7.26 7.01 6.46 7.37 8.02 8.17 8.58 8.33 8.18 9.13 9.38 9.53 10.38 10.13 9.58 10.46 11.11 11.26 12.24 11.59 11.44 12.41 1.06 1.21 2.49 2.24 2.09 3.02 3.27 3.42 4.46 4.21 4.06 5.19 5.44 5.59 7.05 6.40 6.25 7.14 7.39 7.54 8.48 (Halt) 8.23 8.08 Item No. : 02 Ref. No. G/54623/2017/A Agenda :- To consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of a suitable stage carriage on the route Chengannur – Pandalam via Madathumpadi – Puliyoor – Kulickanpalam - Cheriyanadu - Kollakadavu – Kizhakke Jn. -

S.No. Channel Name S/L Service Name S/L Channel Name S/L Channel Name 1 CTVN 1 CTVN 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 2

ICNCL - FTA Pack - West Bengal - Site 1 ICNCL - FTA Pack - West Bengal - Site 2 ICNCL - FTA Top-up - West Bengal - Site 1 ICNCL - FTA Top-up - West Bengal - Site 2 S.No. Channel Name S/L Service Name S/L Channel Name S/L Channel Name 1 CTVN 1 CTVN 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 1 SITI Bhakti Bangla 2 Naaptol Bangla[V] 2 Naaptol Bangla[V] 2 SITI Music 2 SITI Music 3 DD Bangla 3 DD Bangla 3 SITI Events 3 SITI Events 4 Sangeet Bangla 4 Sangeet Bangla 4 SITI Events 2 4 SITI Events 2 5 Music F 5 Music F 5 Channel Vision 5 Channel Vision 6 Orange TV 6 Orange TV 6 Sristi TV 6 Sristi TV 7 Kolkata Live 7 Kolkata Live 7 Sonar Bangla 7 Sonar Bangla 8 Khushboo Bangla 8 Khushboo Bangla 8 Sristi Plus 8 Sristi Plus 9 R Plus 9 R Plus 9 Globe TV 9 Globe TV 10 Calcutta News 10 Calcutta News 10 Tara TV 10 Tara TV 11 Kolkata TV 11 Kolkata TV 11 Music Bangla 11 Music Bangla 12 Home Shop 18 12 Home Shop 18 12 SITI Cinema 12 SITI Cinema 13 DD India 13 DD India 13 SITI Tollywood 13 SITI Tollywood 14 DD National 14 DD National 14 S NEWS 14 S NEWS 15 DD Bharati 15 DD Bharati 15 High News 15 High News 16 DD Kisan 16 DD Kisan 16 Artage News 16 Artage News 17 WOW Cinema 17 WOW Cinema 17 Uttorer Khobor 17 Uttorer Khobor 18 NT1 18 NT1 18 Jayatu Bangla 18 Jayatu Bangla 19 Cinema TV 19 Cinema TV 19 Channel 10 19 SDTV Prime 20 ABP News 20 ABP News 20 SDTV Prime 20 Metro 21 India TV 21 India TV 21 Metro 21 SDTV Plus 22 JK 24x7 News 22 LS TV 22 SDTV Plus 22 Home TV 23 LS TV 23 RS TV 23 Home TV 23 Express News 24 RS TV 24 DD News 24 Express News 24 Vision 24 25 DD News 25 Republic -

Directory 2017

DISTRICT DIRECTORY / PATHANAMTHITTA / 2017 INDEX Kerala RajBhavan……..........…………………………….7 Chief Minister & Ministers………………..........………7-9 Speaker &Deputy Speaker…………………….................9 M.P…………………………………………..............……….10 MLA……………………………………….....................10-11 District Panchayat………….........................................…11 Collectorate………………..........................................11-12 Devaswom Board…………….............................................12 Sabarimala………...............................................…......12-16 Agriculture………….....…...........................……….......16-17 Animal Husbandry……….......………………....................18 Audit……………………………………….............…..…….19 Banks (Commercial)……………..................………...19-21 Block Panchayat……………………………..........……….21 BSNL…………………………………………….........……..21 Civil Supplies……………………………...............……….22 Co-Operation…………………………………..............…..22 Courts………………………………….....................……….22 Culture………………………………........................………24 Dairy Development…………………………..........………24 Defence……………………………………….............…....24 Development Corporations………………………...……24 Drugs Control……………………………………..........…24 Economics&Statistics……………………....................….24 Education……………………………................………25-26 Electrical Inspectorate…………………………...........….26 Employment Exchange…………………………...............26 Excise…………………………………………….............….26 Fire&Rescue Services…………………………........……27 Fisheries………………………………………................….27 Food Safety………………………………............…………27 -

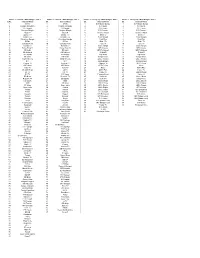

LIST of FARMS REGISTERED in ALAPPUZHA DISTRICT * Valid for 5 Years from the Date of Issue

LIST OF FARMS REGISTERED IN ALAPPUZHA DISTRICT * Valid for 5 Years from the Date of Issue. Address Farm Address S.No. Registration No. Name Father's / Husband's name Survey Number Issue date * Village / P.O. Mandal District Mandal Revenue Village 1 KL-II-2008(0005) T.K. Koshy Vaidyan Shri Koshy Vaidyan Mappillai Veettil Karthikappally - 690 516 Alappuzha district Karthikappally Karthikappally 255/2, 256/17 04.08.2008 91/4A, 5A, 5B, 131/12-1, 27A, 91/43, 90/3A, 2 KL-II-2008(0006) Abraham Joseph Shri Ouseph Nediyezhathu Vayalar PO- 688 536 Alappuzha district Cherthala Vayalar 15 04.08.2008 K. Ardhasathol 3 KL-II-2008(0007) Bhavan Shri Kandakunju Thattachira Vayalar PO Cherthala Alappuzha district Cherthala Vayalar 14/2, 10/2/A2 04.08.2008 4 KL-II-2008(0008) N.J. Sebastian Shri Ouseph Narakattukalathil Vayalar PO Cherthala Alappuzha district Cherthala Vayalar 2/2-B, 3-C, 4-13 04.08.2008 5 KL-II-2008(0009) T.B. Mohan Das Shri Divakaran Puthenparambil Kadakarapilly PO Cherthala Alappuzha district Cherthala Pattanakad 399/31, 33, 34 04.08.2008 218/12-2, 6 KL-II-2008(0010) Manoj Tharian Shri Varkey Thariath Kallarackal Kadavil Pallippuram (PO) Kizhekkeveettil (H) Cherthala-688 541 Cherthala Pallippuram 218/11-A 04.08.2008 29/3A, 29/3B, 29/3C, 29/A, 29/B, 9/2-1, Thuravoor - 688 29/1, 29/2-1-3, 7 KL-II-2008(0010) Susan Ouseph Shri Ouesph Kallupeedika Valamangalam (PO) 532 Cherthala Thuravoor 29/2-1 04.08.2008 98/12/2-2, 98/12/2-4, 98/11/A-1-3, 8 KL-II-2008(0012) Francis Kuttikkattu House Ezhupunna South (PO) Cherthala-688 550 Alappuzha district Cherthala Kodamthuruth 61/2/B-4 04.08.2008 14/21, 15/24, 9 KL-II-2008(0013) P.V. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

Economic and Social Issues of Biodiversity Loss in Cochin Backwaters

Economic and Social Issues of Biodiversity Loss In Cochin Backwaters BY DR.K T THOMSON READER SCHOOL OF INDUSTRIAL FISHERIES COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COCHIN 680 016 [email protected] To 1 The Kerala research Programme on local level development Centre for development studies, Trivandrum This study was carried out at the School of Industrial Fisheries, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin during the period 19991999--2001 with financial support from the Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development, Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum. Principal investigator: Dr. K. T. Thomson Research fellows: Ms Deepa Joy Mrs. Susan Abraham 2 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 The specific objectives of our study are 1.3 Conceptual framework and analytical methods 1.4 Scope of the study 1.5 Sources of data and modes of data collection 1.6 Limitations of the study Annexure 1.1 List of major estuaries in Kerala Annexure 1.2 Stakeholders in the Cochin backwaters Chapter 2 Species Diversity And Ecosystem Functions Of Cochin Backwaters 2.1 Factors influencing productivity of backwaters 2.1.1 Physical conditions of water 2.1.2 Chemical conditions of water 2.2 Major phytoplankton species available in Cochin backwaters 2.2.1 Distribution of benthic fauna in Cochin backwaters 2.2.2 Diversity of mangroves in Cochin backwaters 2.2.3 Fish and shellfish diversity 2.3 Diversity of ecological services and functions of Cochin backwaters 2.4 Summary and conclusions Chapter 3 Resource users of Cochin backwaters 3.1 Ecosystem communities of Kochi kayal 3.2 Distribution of population 3.1.1 Cultivators and agricultural labourers. -

Journal December - 2019 Vol

SVP National Police Academy Journal December - 2019 Vol. LXVIII, No. 2 Published by SVP National Police Academy Hyderabad ISSN 2395 - 2733 SVP NPA Journal December - 2019 EDITORIAL BOARD Chairperson Shri Abhay, Director Members Shri Rajeev Sabharwal Joint Director Dr. K P A Ilyas Assistant Director (Publications) EXTERNAL MEMBERS Prof. Umeshwar Pandey Director, Centre for Organization Development, P.O. Cyberabad, Madhapur, Hyderabad - 500 081 Dr. S.Subramanian, IPS (Retd) Former DG of Police, Apartment L-1 Block- 1, Gujan Paripalana, Gujan Atreya Complex, GKS Avenue, Bharatiyar University Post, Coimbatore - 641 046 Shri H. J.Dora, IPS (Retd) Former DGP, Andhra Pradesh H.No. 204, Avenue - 7, Road No. 3, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad – 34 Shri V.N. Rai, IPS (Retd) # 467,Sector-9,Faridabad, Haryana-121 006 Shri Sankar Sen, IPS (Retd) Senior Fellow, Head, Human Rights Studies, Institute of Social Sciences, 8, Nelson Mandela Road, New Delhi - 110 070 ii Volume 68 Number 2 December - 2019 Contents 1 Role of Community Policing in Responding to Natural Disaster - A Study Based on Kerala Floods - 2018........................................... 1 Dr. B. Sandhya, IPS 2 Police Subculture and Its Influence on Arrest Discretion Behaviour: An Empirical Study in the Context of Indian Police .............................................. 41 Satyajit Mohanty, IPS 3 The Dilemmas of Democratic Policing & Police Reforms ........................ 62 Umesh Sharraf, IPS 4 Child Beggary and Trafficking Challenges and Remedies ..................... 68 Dr. M.A. Saleem, IPS 5 Rents, Sanctions for Prosecutions and Corruption Control: Evidences from the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, India........................................ 74 Kannan Perumal, IPS 6 Transfer- Bane or Boon........................................................................................ 90 P.S.Bawa, IPS (Retd) 7 Indian Approach in Ensuring Cyber Safety of Children - An Analysis ....... -

List of Interns for Rural Posting from Medical Colleges

RURAL POSTING OF OUTGOING INTERNS FROM MEDICAL COLLEGES ANNEXURE Intitution Proposed for Sl No. Name Address posting Family Health Centre Agrima, Kavunkal, Ponnnad.P.O, 1 ADARSH ASOK Ezhupunna Mannnachery, Alapuzha-688538 Alappuzha Family Health Centre Vilayil Padeetathil Puthen koyaikakkom, 2 AKHIL BABU Thamarakkualam, Chennithala.P.O, Mavelikkara. 690105 Alappuzha Kattuparambil, nandanam, Family Health Centre 3 AMALA AJAY Nangiyarkulangara.P.O, Alapuzha- Ambalappuzha North 690513 Alappuzha Sreenilayam, Muhamma,.P.O,Alapuzha,- Family Health Centre Cherthala 4 ANASWARA S S 688525 South,Alappuzha Primary Health Centre Puthumana, ITI junction, 5 ANU PHILIP Budhanoor Chengannoor.PO-689121 Alappuzha Cherukarakavil, Varanam.P.O, Primary Health Centre 6 ASHIK C REFEEK Puthanngadi,688555 Ala,Alappuzha Kaleekkal house, Near MSM house, Family Health Centre 7 AZHAR ABDULLAH Kayamkulam.P.O, Alapuzha-690502 Chingoli,Alappuzha Panavelil house, Patanakkad.P.O, Primary Health Centre 8 GIBIN P ANTONY Cherthala, Alapuzha-688531 Vallarpadam,Ernakulam Sreevalsam, Ponnad.P.O, Primary Health Centre 9 GOPI KRISHNA S Mannancherry, Alapuzha-688538 Mannancherry,Alappuzha Vasanthamalika, Pullikanakku.P.O, Primary Health Centre 10 GREESHMA MOHAN Kayamkulam-690537 Muttar,Alappuzha Rajesh bhavanam, Kurattikkadu, Primary Health Centre 11 JAYALEKSHMI A Mannar.P.O, Alapuzha-689622 Muttar,Alappuzha Kalambukattu House, Arthunkal P.O, Family Health Centre 12 LESLIE S JOSE Cherthala, Alappuzha-688530 Thuravoor South,Alappuzha Intitution Proposed for Sl No. Name Address -

A CONCISE REPORT on BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE to 2018 FLOOD in KERALA (Impact Assessment Conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board)

1 A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) Editors Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.), Dr. V. Balakrishnan, Dr. N. Preetha Editorial Board Dr. K. Satheeshkumar Sri. K.V. Govindan Dr. K.T. Chandramohanan Dr. T.S. Swapna Sri. A.K. Dharni IFS © Kerala State Biodiversity Board 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, tramsmitted in any form or by any means graphics, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without the prior writted permission of the publisher. Published By Member Secretary Kerala State Biodiversity Board ISBN: 978-81-934231-3-4 Design and Layout Dr. Baijulal B A CONCISE REPORT ON BIODIVERSITY LOSS DUE TO 2018 FLOOD IN KERALA (Impact assessment conducted by Kerala State Biodiversity Board) EdItorS Dr. S.C. Joshi IFS (Rtd.) Dr. V. Balakrishnan Dr. N. Preetha Kerala State Biodiversity Board No.30 (3)/Press/CMO/2020. 06th January, 2020. MESSAGE The Kerala State Biodiversity Board in association with the Biodiversity Management Committees - which exist in all Panchayats, Municipalities and Corporations in the State - had conducted a rapid Impact Assessment of floods and landslides on the State’s biodiversity, following the natural disaster of 2018. This assessment has laid the foundation for a recovery and ecosystem based rejuvenation process at the local level. Subsequently, as a follow up, Universities and R&D institutions have conducted 28 studies on areas requiring attention, with an emphasis on riverine rejuvenation. I am happy to note that a compilation of the key outcomes are being published. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 03.05

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 03.05.2020to09.05.2020 Name of Name of Arresting Name of the Place at Date & the Court Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Police Officer, Sl. No. father of which Time of at which Accused Sex Accused Sec of Law Station Rank & Accused Arrested Arrest accused Designatio produced n 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 482 / 2020 Sathyalayam,ka 09-05- U/s188,269, 21 manivelika BAILED 1 Ajay Bijukumar ndalloor 2020 270 IPC&5 KANAKAKUNNUsreekanth s nair Male davu BY POLICE south,kandalloor 19:45 OF KERALA EPEDAMIC DISEASES ORDINANC E ACT 2020 1039 / 2020 U/s269, Akhil, age 188 IPC & 24yrs, S/o Saji, 4, 5 & 6 of Chennivilakizhak 09-05- 24 KARAKKA kERALA BAILED 2 AKHIL SAJI kathil, 2020 CHENGANNURSV BIJU SI OF POLICE Male D Epidemic BY POLICE Mannarkkadu, 19:31 Diseas Karakkad, Ordinance 8899903167 2020 & 118E of KP Act PADIKKAPPAR AMBIL 746 / 2020 HOUSE,AROOR U/s188,269 AROOR P/W 09-05- IPC & 4(2)(j BAILED 3 ANTONY JOSEPH Male TEMPLE ARROOR Si Of Police 19,AROOR P 2020 ) r/w 5 BY POLICE JN O, KERALA, Epidemic ALAPPUZHA, Disease ARROOR Ordinance Act & 118 (A) of KP act 628 / 2020 U/s188, 269 IPC & 118(e) of AMBANAKULA NEAR KP Act & 09-05- 25 NGARA GURUPUR Sec. 4(2)(d) BAILED 4 ASIF NOUSHAD 2020 ALAPPUZHATOLSON NORTH P JOSEPH SI Male VELI,MANNANC AM r/w 5 of BY POLICE 19:35 HERRY P W-16 JUNCTION Kerala Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 536 / 2020 U/s188, 269, 270 IPC, Sec.4 Cheppad r/w 5 of 09-05- Muralidhara 20 Village, Evoor Kerala BAILED 5 Jishnu Evoor 2020 KAREELAKULANGARAT.S.Sujith n Nair Male North -

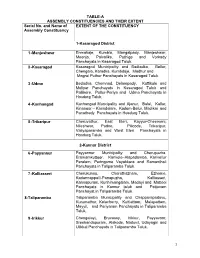

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba